This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Timeless Issue, no. 371, Spring 2023. Order your copy here.

Three Belgians walk into a bar. Or a Zoom call. What happens next is surprisingly unprecedented. This is the first time that fashion’s Holy Trinity – Raf Simons, Matthieu Blazy and Pieter Mulier – are officially speaking together on the record. It’s a conversation that feels both perfectly timely and somewhat overdue. The three first met working together at Raf’s namesake label in Antwerp at the turn of the Millennium, before tackling the Big Apple with their revamp of Calvin Klein, and subsequently landing some of the biggest roles in fashion: Prada, Bottega Veneta, and Alaïa respectively.

Little did we know when we planned the interview that, a month later, Raf would announce the closure of his eponymous label after 27 years in business. For most of those years, Pieter and Matthieu were part of the family – the fraternity, as they call themselves – that questioned and reimagined the shape of modern menswear, constantly pushing the parameters of what youth culture, art and generational disenfranchisement look like when cut from cloth. Over the course of its lifespan, Raf’s independent label would come to embody a new voice in fashion, and one that spoke of their cultural and aesthetic obsessions: warehouse raves; Brutalist architecture; Catholic schoolboy uniforms; goth, post-punk and new wave music; contemporary art; the graphic design work of Peter Saville; David Bowie; Kraftwerk; techno; Factory Records; the Bauhaus.

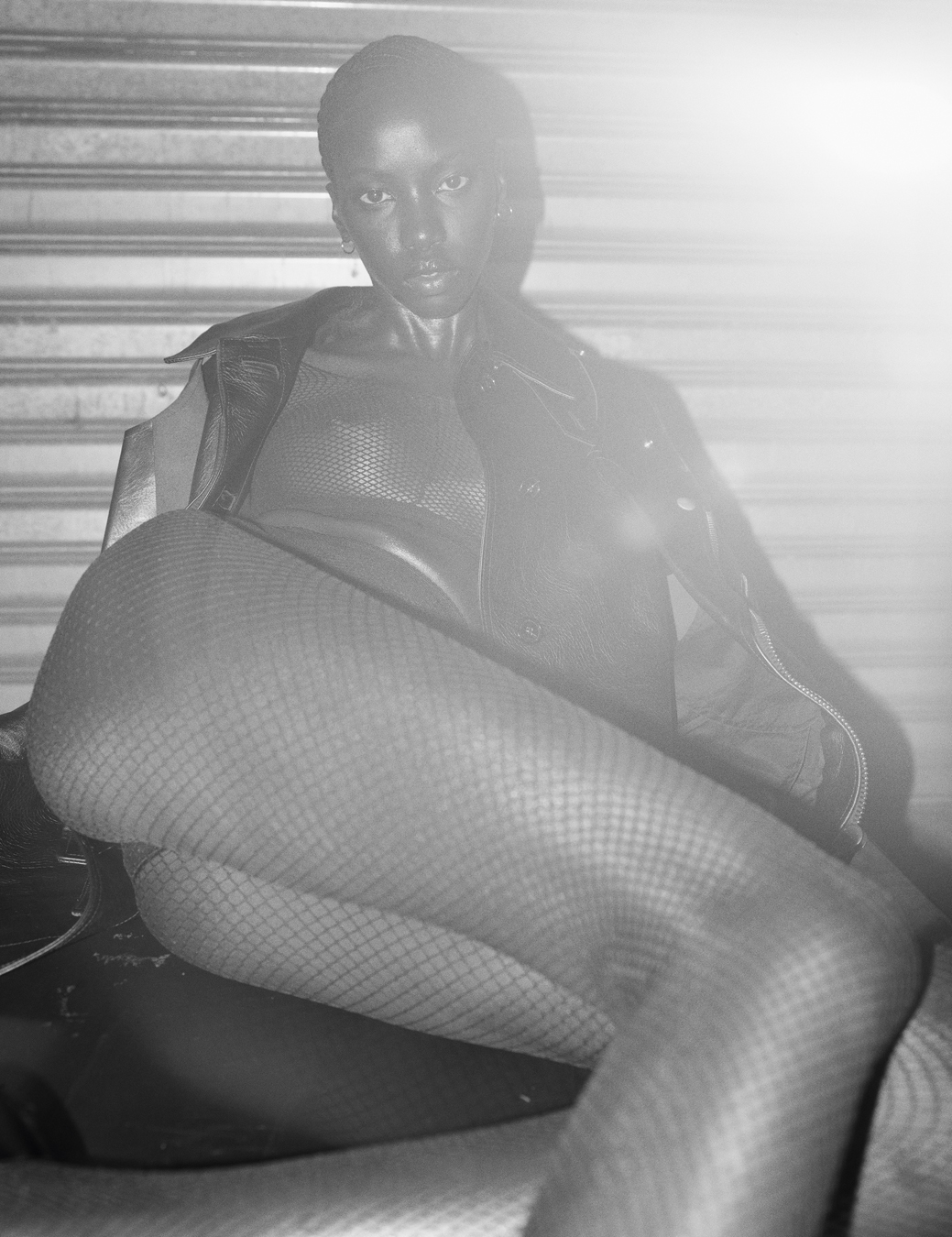

Many of those obsessions came full circle at Raf’s final show, held in London – a city he has looked to since he was himself a Catholic schoolboy in the small Flemish village of Neerpelt, with a record store and a newsstand as his sole cultural reference points for discovering what was going on in the rest of the world. It was his first show on British soil, and also the last. It took over the cavernous techno club Printworks with a thousand-strong audience of students, artists, designers, gallerists, musicians, DJs, and i-D readers (we partnered with Raf on the event) who jostled along the bar- cum-catwalk, drinking beers and vodka sodas as green strobe lights pierced the air of the show.

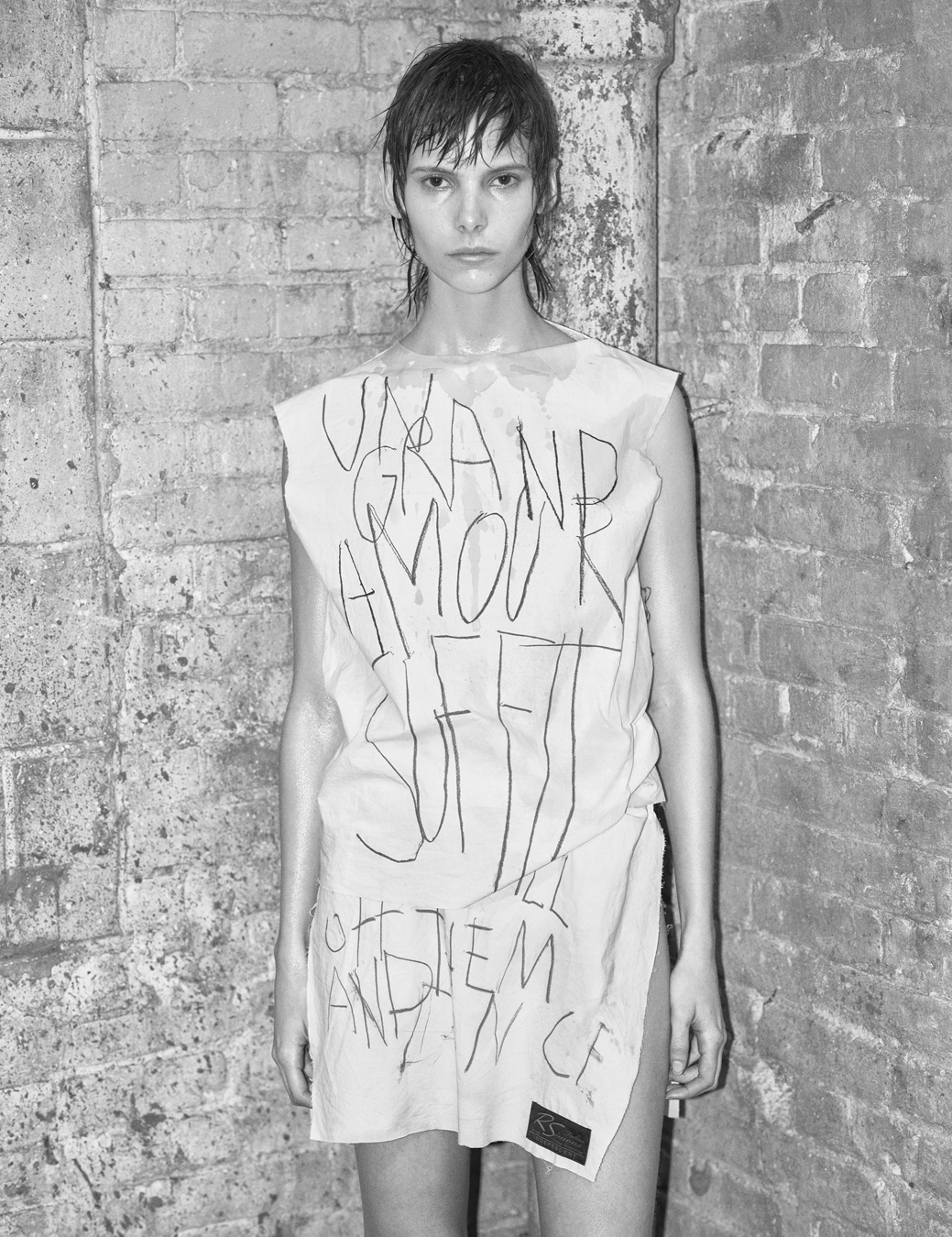

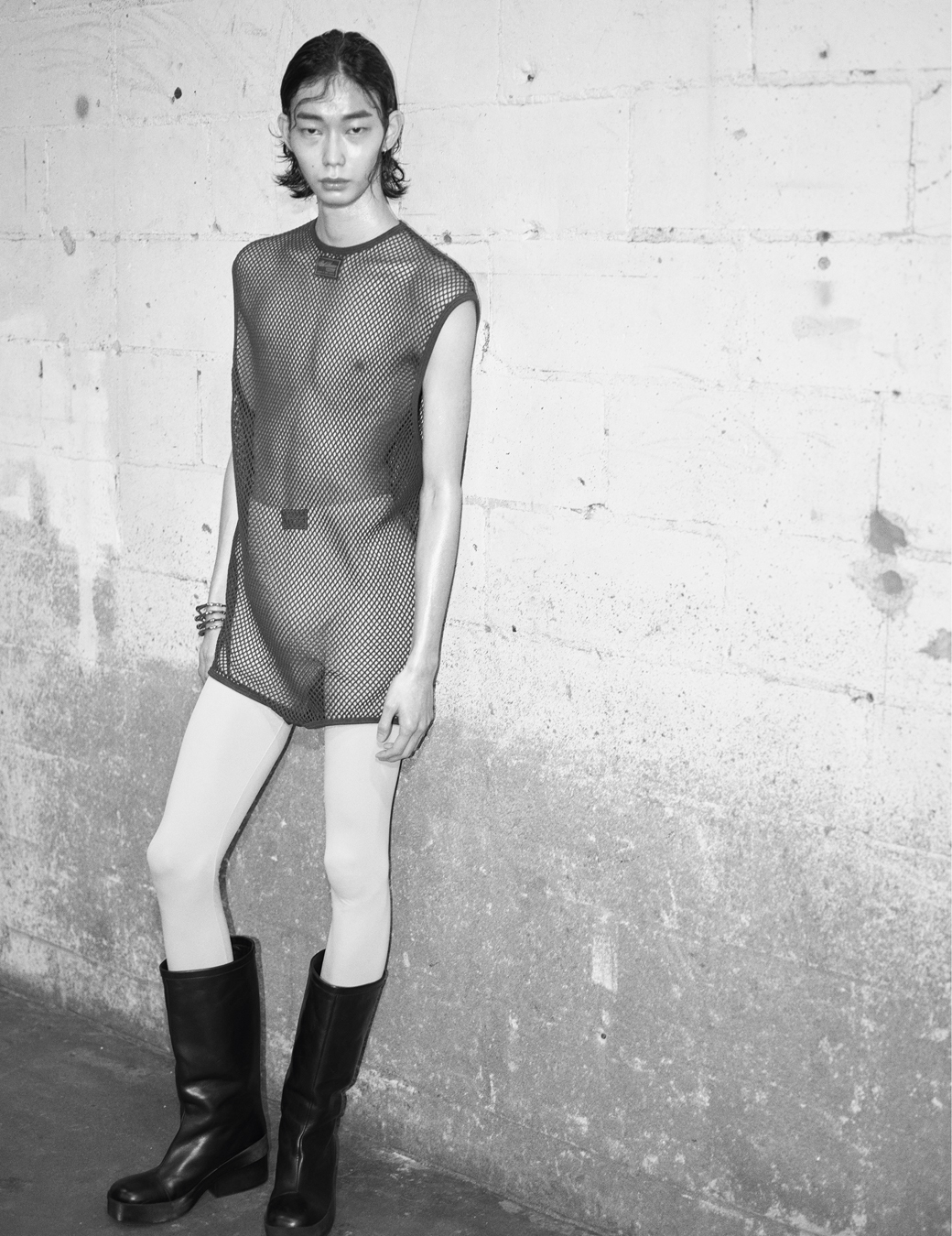

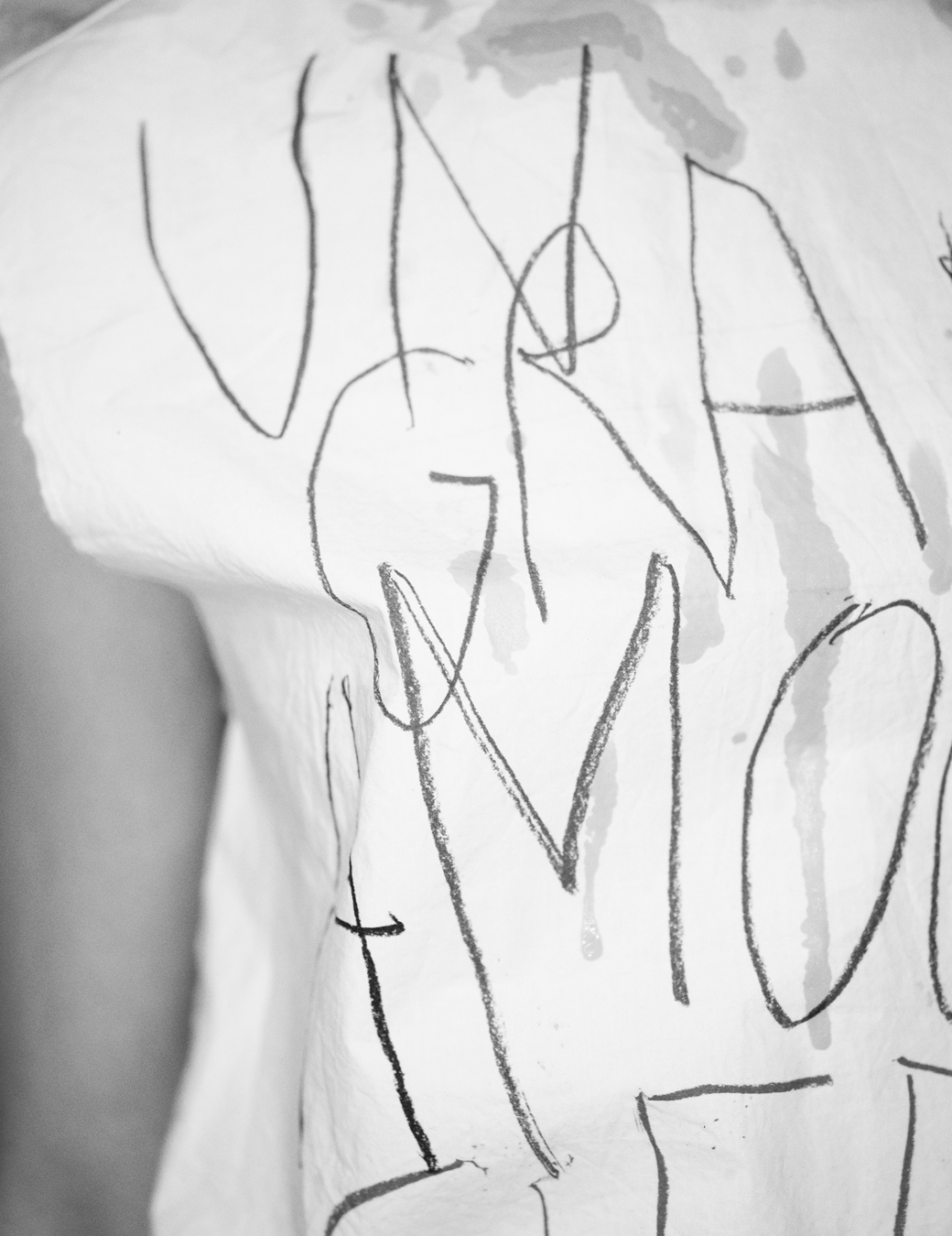

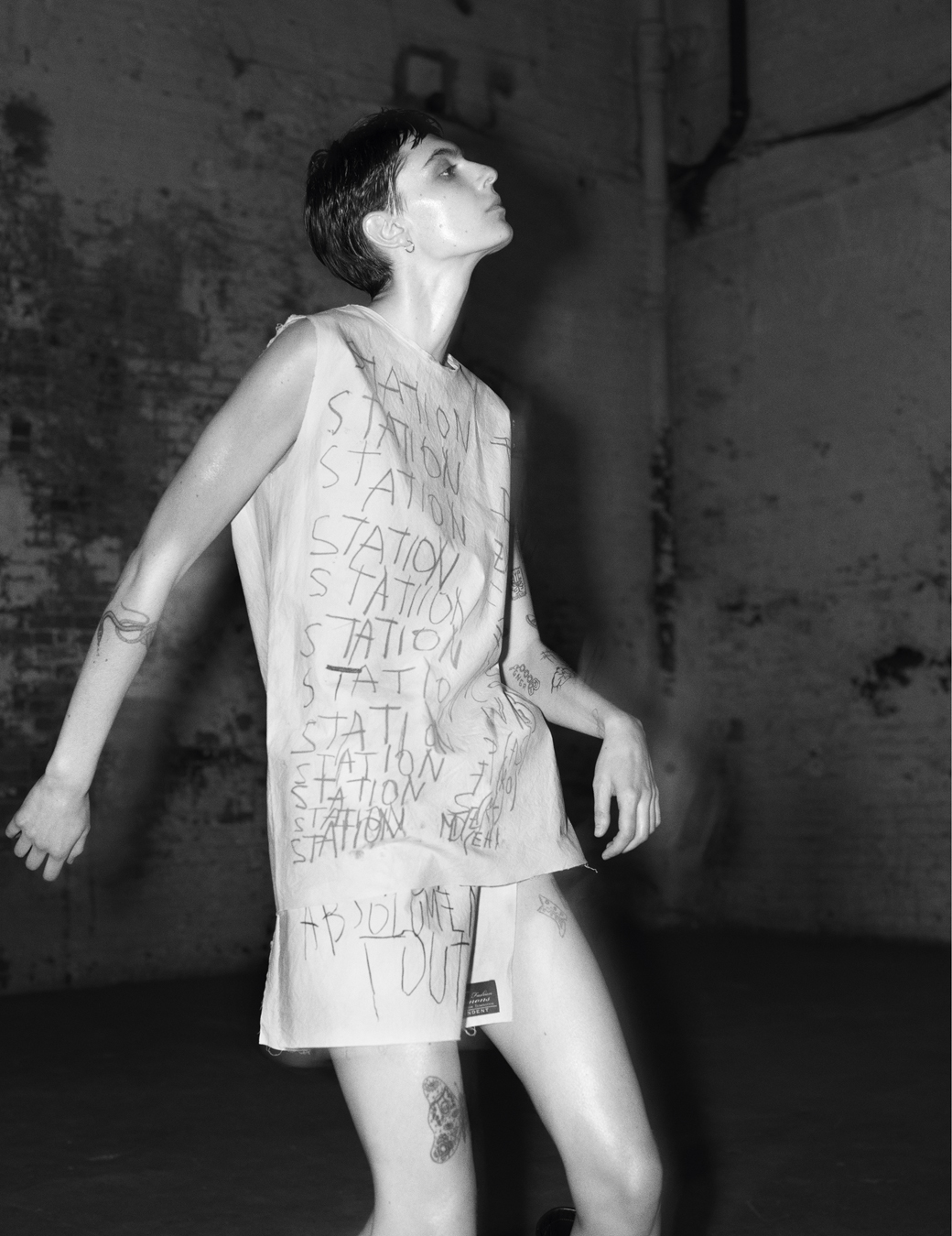

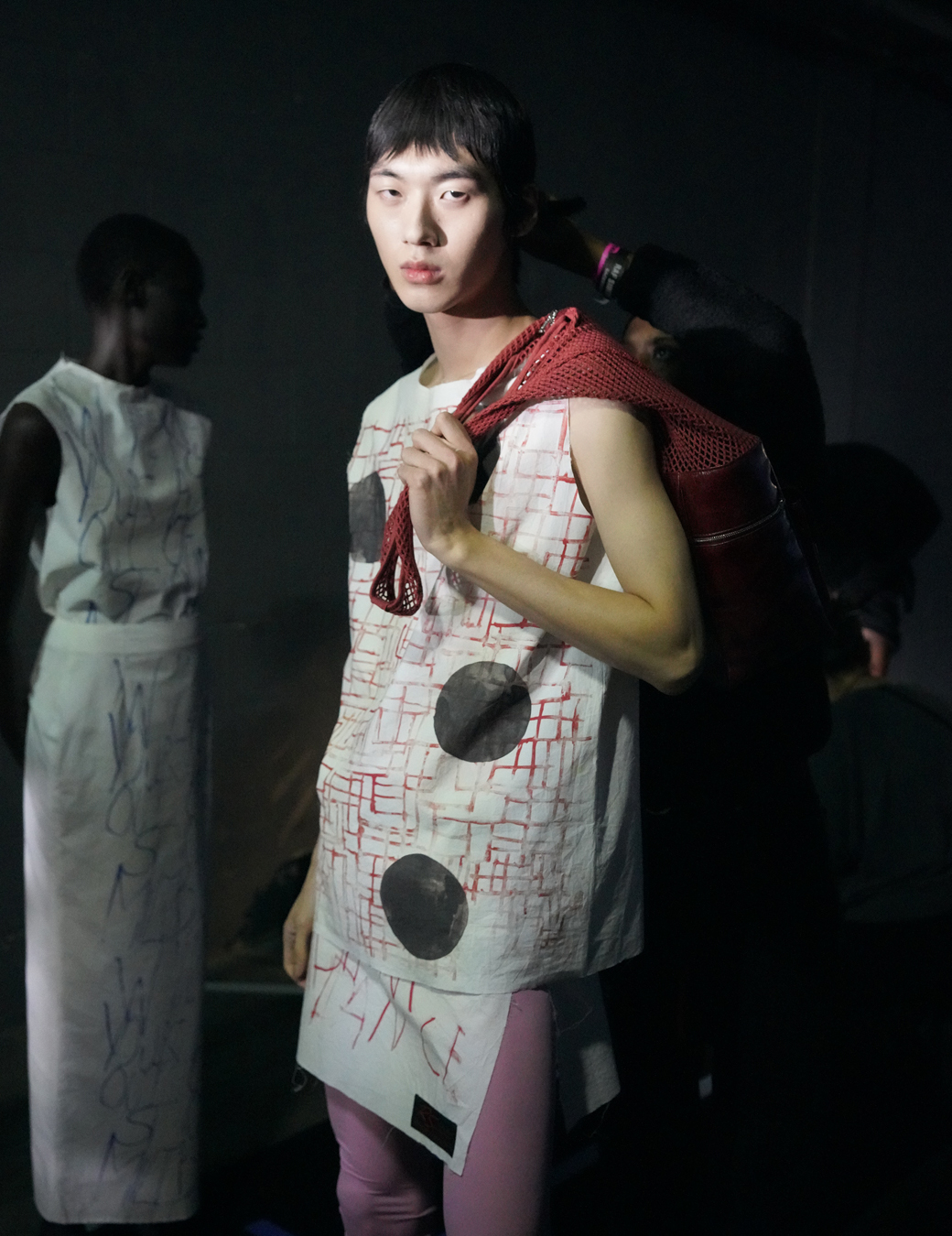

The collection, however, looked to the stripped-back, agile clothing of classical dancers rather than ravers, inspired by some of Raf’s favourite choreographers, such as Michael Clark, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, and Justin Peck, and how they deconstructed the classicism of ballet to create new forms of contemporary dance. It would be too expected of him, Raf decided, to riff on the British references that have always been present in his work. Instead, he found guidance in the work of the late Belgian artist Philippe Vandenberg, whose childlike scribbled phrases, sometimes etched in his own blood, became a key motif in the collection, courtesy of a partnership with the artist’s estate. One phrase, ‘Kill Them All and Dance’, was especially foreboding. “It’s not about people, it’s about giving yourself the freedom to kill your work in order to move on and make new work,” Raf explained in a preview at the time. “It was an interesting way for me to kind of think that maybe, when you’re doing certain things in a certain way for such a long time, and it’s also a nature to do the things you do, that you need to find another angle and make something new.”

So, in many ways, this interview is the story of the Raf Simons label and its family – to borrow a word that Raf, Matthieu and Pieter return to again and again throughout their conversation. For years, they would pick each and every fabric, inspect them under the studio’s kitchen lighting, develop silhouettes and graphics with their friends, street-cast teenagers at raves and put them on coaches from Antwerp and Cologne to walk in their shows in Paris. Every Thursday, Raf’s mum would arrive at the studio with platters of homemade food, while his dad would fix everyone’s bikes.

“I’ve always liked the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk,” Raf says of the German phrase for a ‘total work of art’, one that embraces a variety of artistic disciplines and forms. In his case, the term easily correlates to the melee of music, nightlife, art, youth culture and, of course, clothes that make up his era-defining practice. But it would be nothing without the family at the heart of it all. In their first interview together, the three of them sat down with i-D to talk about those early days, their unconventional working dynamic, the journey from independent Antwerp to global fashion houses, and the indelible mark on fashion they left behind in their work together.

Although the Raf Simons label may now be gone, its legacy will live on forever – sprinkled throughout the network of fashion houses that the three of them now call home.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

Raf Simons: I’m in a completely different position from when I normally do Zooms. I’m always at my desk, but I thought maybe I need a more comfortable seat for this one.

Osman: You need a comfortable seat and a glass of wine.

Matthieu Blazy: I just got a beer.

Raf: I’m taking a screenshot of this because I think it’s historic.

Osman: This is the first time that you three have done an interview together, right?

Raf: We’ve done other things together… But yes, this is the first interview.

Osman: Then this is historic. I thought a nice place to start is with Matthieu and Pieter. When did you both become aware of Raf Simons, the man and the brand?

Matthieu: I got to know Raf through a woman, Maria Luisa Poumaillou, who used to have a store in Paris. The first time I met her she said that Raf was the only one whoever really understood how to cut a trouser. That was the first time I heard about Raf. The rest came through curiosity, looking at his work in i-D, studying, arriving in Belgium, and getting to know the fashion landscape. That’s how I got to Raf, by name.

Pieter Mulier: My ex-girlfriend had one of Raf’s catalogues in her bedroom on the wall. The one with all the portraits from the Isolation show (1). She always said I had to buy it, but I didn’t have the money.

Raf: He only had the money for corduroy pants from Dries (laughs). Pieter and Delphine – Pieter’s girlfriend at the time – were studying interior design together and I ended up being on the jury of their end-of-year project. They had to make something.

Pieter: Survival was the theme!

Raf: Yes, so many of the kids were doing, I don’t know, some kind of metal armour so that if they would be attacked in the street, blah blah blah. Pieter had made an outfit based on a book that outlined everything you needed to remember when going for a job interview – you know, like making sure your shirt is tucked in. So he had this outfit which was all in one piece so that nothing could go wrong. I thought it was such a different angle to think like that – how to survive a job interview. So I had an instant interest in him. Also, I remember him presenting it…

Pieter: I was wearing it.

Raf: So I thought, ah, we have somebody who can get a suit and can perform and is assertive in talking! But actually, I think you asked me if you could come and to do an internship with me. I don’t think that I came and asked you, but I don’t remember that.

Pieter: I remember you gave me a card and I called you the day after.

Raf: I think that the first day you worked was my Kollaps show (2). We found out afterwards that the location for the show was actually Matthieu’s school (3) – and this was way before I met him. And that’s how Pieter started. You came and then you stayed. The company was very small at the time. I think at one point it was just four people or maybe even three.

Pieter: I went back to school to graduate, but I came to work every week for two and a half days for the next six months. And then I stayed.

Raf: Then Matthieu I met in Trieste, at the International Talent Support contest. There were all these students and Cathy Horyn (then The New York Times’ fashion critic) was there as well. I remember very well that right after you presented, Cathy and I looked at each other and were like, “Oh, this is clear as water. It’s him. Nobody else. It’s impossible.” But then he didn’t win, which we completely disagreed with.

Matthieu: You invited me to Paris and I went to see your show. And then you said, “The only way you can enter my company is if you meet Pieter.” So I went from my graduation to this interview with Pieter, which was amazing. And then I started ten days later.

Pieter: It was a big thing, because we’d never had a new person.

Matthieu: I was extremely stressed. The interview happened in your office, Raf, which I didn’t realise. I was like, “Fuck, this is Pieter’s office. Wow. What is Raf’s office like then?”

Pieter: My office was the kitchen.

Raf: My life was kind of fucked up at that time because I had stopped and then I had started again. I skipped one season, although at the time that I stopped, I thought it was not for me, I don’t want to do fashion. Then I missed it and I came back. That’s also why the operation was so small because before I stopped, we had seventeen or eighteen people and it was all moving way too fast. So I kept a creative office with basically only two people. That’s how it was when we did the Manic Street Preachers (4) collection, the show was done with only two people: Priscka, me and Robbie Snelders (5). And then after Kollaps, we had Pieter. But when we moved to the new space, it was not only an office, it was also where I lived. Pieter stayed there during his internship.

Pieter: I had a mattress under the archive and I slept there for a year. In the morning everybody came to wake me up when they arrived for work.

Matthieu: When I started, every meeting happened in the kitchen.

Raf: I liked the lights there. It was the only place where we could choose fabrics.

(All three start smoking)

Raf: I was really timing how long was it going to take before we all had a cigarette.

Osman: So Pieter, you were living there at one point, Raf, you were living there. So in terms of the work-life balance…

Raf: Zero.

Pieter: We were living together and then Matthieu, when you joined, we’d go out together in the evenings. We would have dinner together in the office very often.

Raf: The bistro near the studio became my kitchen because my apartment was at that time also the office, and I had a tiny shower and sink.

Pieter: There wasn’t much separation between work and private life. But I was 22 when I started working with Raf, and Matthieu, you were 23. We both came to Antwerp and I didn’t know anyone. So Raf and the team became family because we did everything together, which was actually very nice.

Matthieu: It was amazing.

Pieter: It’s maybe strange if you hear it now, but back in the day, it was like that. It wasn’t a nine-to-five job. We even cleaned together. I remember when Raf went to Milan to work for Jil Sander (6). It was a week in Milan, a week in Antwerp, and every time you left, we cleaned the whole office.

Osman: When you were together in the studio, what was Raf like as a boss? What was the design process like?

Pieter: Well, it was actually quite classic.

Matthieu: I remember a lot of talk without any images.

Pieter: In the beginning, yes. Again, in the kitchen. Raf would fire questions at everybody that made everyone very uncomfortable. Starting with, “What do you feel?” When I first interviewed with Raf in Antwerp, his only question was, “Okay, top three movies of all time?” And I freaked out. I was like, “Okay, I have to think, I have to be intelligent.” And then Raf asks about my favourite artists. And he wanted contemporary artists. Not Rubens or whatever. You remember that, Raf?

Raf: Now that you say that, yes.

Pieter: So basically the start of a collection was a bit like that. It was everybody around the table, even the fabric girl, even the interns who were already afraid of Raf. Then you would just fire questions, like “What do you feel?”

Matthieu: Collections always started like this, full of questions. Also, I remember my first season we all went together to Première Vision (7). I didn’t know how Raf worked then, but the first hint I got about his method is that he went to the bathroom and saw some rust. I don’t know if you remember. You came out of the toilet and you said, “All right, the collection is done.”

Pieter: Back in the day it used to be a big thing to go to the fabric fair. Remember we were fully Raf Simons, an army of Raf boys walking around. It was actually always fun, no? We used to sleep in a crappy hotel.

Raf: Crappy hotel, crappy food, but we really liked the fabric fair.

Pieter: It was like a moment in the season. We don’t do it anymore, but back then, I remember the new clothes arrived a week before Première Vision from the new collection, so we were all dressed up like crazy.

Raf: Première Vision was such a thing because you would bump into so many big designers. I remember when I went there for the first time, I was struck when Helmut Lang passed by with his two assistants, all in cowboy boots, wearing nylon blazers. So many people were there all the time.

Osman: Between the three of you working together, how would you describe each other in terms of your strengths or points of difference?

Raf: In the beginning, you mean? Pieter was then clearly already my extension. So, in a way, I think that it was very family, very easy, very easy going. If you ask me to describe their personalities, I can: Pieter is a very good leader and organised and assertive, Matthieu, I think you were always very free in your way of thinking. I find it weird that you say you were stressed because, to me, you never really seemed scared to bring ideas, no matter what it was. There was no hierarchy. That’s not really how I operate, anyway. It’s an open field. I like everybody’s freedom to bring things in.

Matthieu: It’s not that you were strict, but I just wanted to do a good job and stay in my position, so I tried to deliver as much as I could. Some ideas were better than others, but it never felt like anything could go really wrong because we loved to experiment.

Pieter: And also, Matthieu, you arrived at the time when we booked models. When I arrived, that wasn’t the case. Back in the day, we used to street cast. We’d stand at schools, go to raves and discotheques to find models. I mean, it was a 24-hour job.

Raf: But we did castings, before the internet, before mobile phones. So, I would sometimes call into this Belgian radio station, Studio Brussel, during the techno hours on Friday evenings, for example, saying that I’m looking for people to walk the show. We did that for quite a few years. We’d hang posters all over the city, and put them in a couple of magazines. And then, out of all of these people who were coming, we would select the boys for the show. None of them were models, but some of them would do the shows season after season. But then we had to stop these castings because, when the brand became more known, too many people would turn up – sometimes, like, six, seven hundred people.

Pieter: We did all the castings and fittings in Antwerp, and then we put everyone on a bus to come to Paris to the show. Then the bus would leave right afterwards. I think that’s also the beauty of it. It was this energy moving from one town to the other and then coming back.

Raf: My parents would always be on the bus. My mum and some of her girlfriends. The parents of the boys, especially if they were very young. That was always very important for us.

Matthieu: Talking about your parents, it’s important to say that every week, Raf’s parents would cook for us in the office. Your mum would prepare a lot of food and come every week on a Thursday. It really felt like a family in that sense. And if you had a bike, Raf’s dad would help you with your bike.

Raf: Yeah. He would always find second-hand bikes for everybody and then make them new again.

Osman: I guess at some point it goes into working for other houses, which is a completely different environment, structure and even city. How does that dynamic, which was so close, translate into when you then started working together elsewhere?

Raf: Well, first of all, I think it was organic. But it was never chaotic.

Matthieu: It sounds very romantic, but something I love about Raf and Pieter is that we spent hours working on the clothes. It was extremely precise. It was a beautiful balance between spending time together – which, at some point became like a brotherhood. But when it came to the work itself, the level of execution was always high.

Pieter: We went quite far sometimes to get ideas done. I’m talking about the time before the big houses. But you remember when Raf came to the office, Matthieu, and he said, “I want a dad sneaker.” We were all laughing. You remember? And we were all laughing like, “Oh, what the fuck!” It was 2007. We’re like, “Oh God, who wants a dad sneaker?” Then one week later, I was on a plane to Hong Kong, developing a dad sneaker!

Matthieu: Raf was like, “It’s going to be the big thing for the next ten years.”

Raf: Do you know the backstory? At one point I thought I needed to start running, and I’d heard you need the right footwear. My whole life I had been only wearing Adidas Stan Smiths. So I went to the store where they measure your foot and do these tests and they came back with the ugliest pair of shoes I’ve ever seen. But also it was genius. It was so off.

Matthieu: I remember we did a collage. We found a very typical childhood cartoon of this man wearing a perfect suit, and then, we had this picture of a guy running. We just folded the paper. We put the shoe under that suit. And typical Raf, he just said, “this is it, the show is done!”

Raf: I don’t think that it’s ever been an easy job to work with me. Yes, on the one hand, there is all the beauty, the freedom, the togetherness, the experimentation. We were always really focused on the runway clothes, no pre-collections, no stores, which meant that we were small. There was no atelier to show a drawing to who would put on a white coat and make it. It was a lot of work.

Matthieu: Raf also was generous enough to give us enough time in those places and factories. Then, we would learn.

Pieter: It was all about the message that Raf wanted to give on the runway, and it needed to be different every season. At Alaïa, I work like that too because it has that sense of luxury, like the Raf Simons brand. The runway is very important. But at other brands that we worked on together, the message we were putting out wasn’t always the most important thing. We never thought about money, or turnover. Ultimately, the education that Matt and I had with Raf was learning to work on a silhouette – to create a silhouette that you haven’t seen, or at least not for a very long time. And that’s especially difficult with menswear, but it would always be our starting point. Once we found the answer, though, we started flying around, making it happen.

Osman: So, what was it like going from this independent hands- on studio, to working together again at Calvin Klein in New York?

Matthieu: We had experience already when we were at Calvin. Raf had been at Jil and Dior, and Pieter was at Dior, too, and I’d worked at Margiela and Céline (8). We knew the industry better. Producing the collection was not the challenge, the challenge was really to propose something radical and, at the same time, to create a product.

Pieter: Also, Calvin was quite peculiar, right? Because it was such a big company with so many layers and I think that was the most difficult part. What was nice was going to New York together. The idea of us three in New York battling this big animal, but also the city itself, that idea was quite romantic.

Raf: I think so, too. I feel that sometimes, because of how it ended there, that people almost avoid talking to me about the Calvin Klein period. But honestly, I think that, for us, there was also enormous pride in what we did there.

Matthieu: And joy!

Raf: Pieter was the creative director of Calvin Klein. I was something they called Chief Creative Officer.

Matthieu: I was Vice President of Design, sort of like the Michelle Obama of Calvin. (Laughs) One word I’d use to describe our working relationship is alchemy. It was always a discussion. You know what I mean? It never felt restrictive. Everything was welcome.

Raf: It was obviously very complicated. Sometimes, when I think it over, I think, “Were we so green to believe in what we did?” I don’t know how to explain it, but the runways there had, for us, the same excitement as what we did together for Raf Simons. With all respect to Francisco (Costa) 9, it was not a brand that had a big distribution anymore. And I think we did get very quickly a big distribution, probably to the disappointment of the people who really are in charge there.

As Pieter said, it’s extremely big and multilayered, so it’s not only about the creative director and CEO. There were many people involved. I really don’t want to say anything negative, except to say that the last months were ugly and very wrongly communicated and reported in the press (10). But you can’t really control a situation like that. From a cultural and political point of view, we cannot forget that Trump was elected soon after we arrived. It was impossible not to comment on it. I really wanted to have meaningful runway collections that related to real fashion. Personally, without sounding pretentious, I think we brought the brand into the spotlight again very, very, very quickly, which is a credit to the boys here and all the teams that worked on it.

But I think that part of the problem was that, even if there was quite a big global distribution and we saw the collection in stores around the world, that turnover was nothing compared to their billions. Can you expect to do that with high fashion? After a few years, maybe, but that was perhaps something that I hadn’t taken into account before making the decision to go there. But we had an incredible time and experience, too.

Pieter: But the good thing is that, even with all the problems, we had that experience together in another company. It felt like something fresh. And it was quite reassuring to arrive there with people that you know. Because it’s so big and so impersonal that at least the basis was us three looking at everything.

Raf: I also think about the physicality of that situation for me, which was partly that, even if the structure was way bigger, in the end, there was just us. It was this huge building but also we had an intimacy that sometimes made me think of Antwerp.

Matthieu: At Calvin, whenever Raf and Pieter were having a meeting with the marketing or merchandising team, they would get me to come and step in and give my opinion. I was never just facing Raf or Pieter with a shirt. It was always a bigger discussion. And you could have a say in it, or at least give an opinion, and you were never pushed away.

Osman: What I find really interesting is that since then, all of you have gone on to three major fashion houses, and in each of your roles you’ve been very smart and have really pushed what branding can look like or what collaboration can look like. For a long time, it has been very formulaic and very traditional. Each of you have taken that apart.

Raf: When I went to Dior, it was with Pieter. At Calvin, it was again this family trio, which is very different, I think, from Pieter at Alaïa and Matthieu at Bottega. I’m kind of fascinated to hear how that feels for you both, doing it all by yourselves.

Pieter: For me, it was actually very easy. No, really. It was easy after Calvin. I’m a people person and Calvin was too big. We did 55 collections with 30 teams worldwide. I didn’t want to work like that again. It’s not human. It takes away from what I actually like the most about fashion, which is product. So, when Alaïa called and explained the structure to me, saying that it would be a studio of two people, that I’d have to come alone, there wouldn’t be a stylist, but I’d have an atelier of 45 people, I thought, “Heaven.” When I arrived, they didn’t even give me an office. It was like how it was before with Raf. The only difference was that I wasnow the Creative Director of a company without him (11).

I do sometimes wonder what Raf would think of what I do during fittings, but now it’s like two and a half years down the line, so that happens less and less – which is a good thing, I think!

Matthieu: For me, it was different because I had already worked in other companies without Raf and Pieter, at Margiela and at Céline with Phoebe. When I arrived at Bottega as a design director I knew how to navigate it. When they gave me the keys, obviously I was lucky because I’d worked a lot with the team already. I think the challenge was to maintain the relationship with the people in the company as well. But voila! Every day is a new challenge.

Pieter: We talk a lot about fashion now, but, in the studio in Antwerp, we talked a lot about art – more so than fashion, sometimes. We did art fairs together. We went to Frieze together, and Basel. And I think because, Matthieu and I, we started very young, Raf opened our minds beyond fashion. Through him, we learned how to look at the world. You always need one or two people to push you, whether it’s a teacher or a professor at university, or it’s your father or mother. I think for me, it was Raf. He was that somebody that pushes you and makes you aware of what you can do.

Osman: Raf, what’s it like to hear that?

Raf: When you work together and start realising that you’re working with the right people, it also works the other way, too. It might sound like I am the one who knows it all, but I’ve always looked towards the people that I admire for who they are and what they think. When you are in these big structures, it doesn’t all come from one person anymore. It’s not like that. I’ve always liked the idea of Gesamtkunstwerk (12). For me, that’s especially relevant in fashion, because it’s such a social kind of expression. It’s different from being an artist. I think the dialogue with somebody who could technically be seen as the person under you – like your right hand or your design director – is so crucial.

It’s not so important what the position is. The most important thing is that you’re working with the right person with the right way of thinking.

Pieter: You know what many people ask me in interviews? It’s very strange I think, and I always answer the same. A lot of people ask me, “Why did you stay with Raf for sixteen years?” And I always answer the same, “Because I was very happy.” I was still learning with every step, which is rare nowadays.

Raf: Maybe also it stayed challenging. I don’t think it’s always been easy for them, definitely not for Pieter. But it kind of stayed exciting and I also remember the moments when it was really the moment for them to fly out. Even prior to them at Alaïa and Bottega, which are all very recent, I could feel very much the limitations of what I could offer. And out of that came, also, Pieter’s position at Dior because he was really, really keen on doing womenswear and that was not part of what was possible at my brand at the time. And with Matthieu, he really designed for women. For me, it was a little sad that the world was not allowed to know that Matt was the creative director of Margiela, but people were not supposed to look.

Osman: Now, it’s a little network of Raf Simons alumni that are running fashion. When we decided to do this interview, we didn’t know that you would be closing your label, and it’s interesting to consider the influence of it and what it has contributed to fashion.

Raf: It’s not the easiest thing for me to talk about, to be honest. As you can see from the way it was communicated, it was a very personal decision, and a very difficult one, mainly because I have to deal with the team. But when I started, it was never my intention to do this for a lifetime. It’s very difficult for me to explain, but it just felt like the moment to stop. It wasn’t an impulsive decision, though. Of course, the first reaction for many people was to assume I was sick, or the company was doing really badly financially. But I’m healthier than ever and we’re doing better than ever with sales. The London show did extremely well, so it’s nothing to do with that. I’m very aware of how people see and experience the brand, how it’s in their system, their life. I got such an incredible reaction.

Osman: To your point, I think that fashion is, at its best, very instinctual. And what you were saying, it’s not always about a business decision, it’s a feeling, an emotional or an instinctual decision: that actually makes people respect that decision even more. It’s an incredible thing to say, “I want to do it on my own terms.”

Raf: In my opinion, many people should stop. There’s so much bullshit out there. I want to be positive about fashion, especially for the younger generation. I’ve always really encouraged the young generation, but I think that it’s almost a natural evolution that every young generation thinks that they have to follow the system, and I don’t believe that is a stimulant for meaningful creation. Maybe I feel like this because of what I experienced when I was young, and I saw Helmut Lang and Martin Margiela and they had new voices – they really wanted to change fashion. In my opinion, that’s not the driving force for most of the people that are now coming into the industy. But I don’t blame anybody. Maybe it’s just a natural evolution.I honestly think that if it goes in a different direction, it will only be possible for very young, new people coming in. The system is extremely evolved now.

Pieter: But I think what has changed since when we were younger is that fashion, and its audience, is much larger.

Matthieu: Yes. We design for the whole world now.

Pieter: Back in the day, we did not design for the whole world. We designed for a small part of the world.

Raf: I am all for democracy as well. I love the idea, and I always quote the same person, Peter de Potter who said a long time ago: “Fashion is the new pop.” I remember that and will never forget it – he was a visionary thinking that, because that’s what it was.

Matthieu: But also, when I was a student, I would go to shows: you would go to an Ann Demeulemeester show, you would see the Ann crowd. You go to a Raf show, you would see the Raf crowd. I think there was something quite incredible about the kind of audience because, no matter where they came from in the world, they belonged to a community. In terms of identity, it was fascinating.

Osman: When I started, designers used to always say, “Oh, I have a woman,” or, “I have a man.” They would really have this idea of who it was they were designing for.

Matthieu: Nowadays people just jump from one show to the next. So they might dress for one, and then they change.

Pieter: Rick Owens is the only one who still has it.

Raf: I think that’s incredible, actually, especially when you think of where he comes from and what was prior to him. He is almost like the last man standing. It’s actually really admirable. But I think the problem is that the judgement on fashion brands these days is really about scale. People talk about how well handbags sell or whatever, but why is it not still interesting to be very small but very meaningful? Because it’s the actual creation that matters most. What you described before about the clan, the group, the community… Every label still has its community. I think it still exists, but it can be very big, and it doesn’t really translate into the way we used to know it.

When you would go to Paris during fashion week, you really had the Helmut people, the Margiela people, the Gaultier people. I think that people were more into one brand, or maybe a few brands, like they were into the Japanese deigners, for example. That has changed a lot. It diffuses things, it becomes more of a blur. A lot of people in our generation were very extreme. “This and this we love, and all the rest, we don’t like.” I don’t think most people are like that anymore. I think they can appreciate a lot, which is, in a way, also a beautiful thing, but it makes things less specific.

Rick Owens is a very good example. People that love Rick, they’re really not going to buy Versace bag or a Gucci shoe. It’s all about Rick’s world, Rick’s vision and his aesthetic and all the darkness that comes with it. That’s what it is about. And that’s how we were raised, with the Ann Demeulemeester people, the Margiela people, the Dries people. You’d go to a Comme show and everybody was dressed in Japanese fashion. It didn’t even necessarily mean that it’s all Comme des Garçons on your body, but the community was expressing a certain, specific language of clothing.

Matthieu: A lot of young people are just discovering your work now as well. For example, I have this kid at Bottega who is twenty years old. He discovered your work two years ago, and is obsessed.

Osman: I think the thing that I’ve taken away from this conversation and a lot of young people can take away is essentially finding your tribe and really working together as a family.

Raf: I remember people graduating from the school where I was teaching, worrying in the years after, about, “Oh my god, where should we put on a show? Should we do it in Paris, or should we do it in Milan? Who should be the press agent?” I think I said this before, earlier, a long time ago in an interview: I thought, “But it’s not what you should worry about right now.” What you should worry about is making something that has not been seen, and then people will find you. There will be an audience for you. I believe that there is still an audience out there that will always want to have something that they don’t know yet. Maybe it’s a small part of the crowd, but it’ll still always exist, and that is the beauty also.

Pieter: I agree.

Osman: I know that you all collect art. Do you have similar tastes? Is there any crossover in the art that you love or that you collect?

Raf: Yeah, a lot.

Osman: How do you all decide who gets what?

Matthieu: We call each other.

Pieter: Well, no. The rule is, Raf always wins.

Raf: No, no, no, no, no, no.

Pieter: I’m joking. When we buy stuff, and Raf likes it, he always says, “Oh good, I can borrow it from you then.”

Osman: My last question is, now that the three of you don’t work together, when you are all togethers in the south of France on holiday, what does your friendship look like?

Pieter: We don’t really talk about fashion.

Matthieu: We talk about the dog, we talk about art, food.

Pieter: But we really don’t talk about fashion. Not even after a show.

Raf: But I don’t talk about fashion anyway, anymore. (laughs)

Matthieu: A month and a half ago, and after one hour and a half of us all together, we were like, “Shit, we didn’t even speak about fashion yet!”

Raf: The beautiful thing is that we all have a very good understanding of when it’s time to take time off. So when it is that time, we’re definitely not going to annoy each other with the stress of work or anything like that.

Matthieu: But also, all the weekends we spent watching movies, eating ice cream. When we were in New York it was really about, what are we going to eat? What’s the movie we’re going to watch?

Pieter: If we ever talk about fashion it’s about fashion we don’t like. And that honestly can take a long time! But once we spit it out, it’s out there and we don’t do it anymore. If we talk about fashion, it’s mostly that. It’s more like a bitchy brunch.

Notes

- In 1999, Raf presented an almost all-black collection titled Disorder —Incubation—Isolation that opened with three models carrying flags, one with each word on it, taken from three Joy Division songs.

- Presented nine months before 9/11, Raf’s SS02 collection was eerily prescient, featuring wrapped and masked models holding torches to a soundtrack of Fuse and The Fall. Peter de Potter’s graphics featured aggressive slogans like “Be pure, be vigilant, behave”, a lyric from a Manic Street Preachers song, another long time Raf obsession. The collection would come to define the fear and angst of a world preoccupied with safety and terrorism.

- The show was held in a 6th arrondissement lycée in Paris, with models walking barefoot in the darkness.

- AW01 marked Raf’s return to fashion after a year-long sabbatical with a collection inspired by young urban radicals, titled Riot Riot Riot. Flyers, posters, and photographs were haphazardly tacked onto garments, among them several photos of the band Manic Street Preachers and a police blotter report from the disappearance of their guitarist and lyricist Richey Edwards in 1995.

- Priska Morger was Raf’s assistant from 1997-2000. Robbie Snelders, who was initially a fit model, came to embody the Raf Simons ‘man’ on the cover of the designer’s monogram, The Fourth Sex, a Mickey Mouse painted on his face and a distressed Raf hoodie and schoolboy blazer slung over his frame, as well as an iconic i-D cover from 2001, both photographed by Raf’s longtime collaborator Willy Vanderperre. He ended up working in the studio, alongside the team.

- In 2005, Raf Simons joined Jil Sander as Creative Director, splitting his time between the house’s base in Milan and Antwerp. It marked his debut in designing womenswear, which would later lead him to Christian Dior in 2012. Pieter joined him at Jil Sander, designing footwear part-time.

- Founded in 1973, Première Vision is the world’s largest fabric trade fair, most famously held in Paris, where many designers initially source materials and negotiate their supply chain for upcoming collections.

- After working on the Raf Simons label, Matthieu departed to become the head designer at Maison Martin Margiela in 2012, following the eponymous designer’s departure from the house. Although he was responsible for some of the brand’s biggest moments, such as the crystal studded face masks that became a feature of Kanye West’s 2013 Yeezus tour, he was not publicly recognised as the designer until Suzy Menkes revealed his name and position on Instagram. In 2014, he joined Phoebe Philo’s Céline as a senior designer, where he worked on the pre- collections.

- In 2016, Raf was appointed and named chief creative officer at Calvin Klein, succeeding its previous designer, Francisco Costa. In this role, however, Raf oversaw all the brand’s many diffusion lines, from Calvin Klein Collection to Calvin Klein Home, and rebranded the brand’s New York Fashion Week runway collections as ‘Calvin Klein 205W39NYC’. Pieter joined as the Creative Director, and Matthieu as Vice President of Design for womenswear and menswear. It marked the first time the three had worked together since their days in Antwerp.

- In the months before Raf’s departure from Calvin, gossip swirled about heavy discounting and chasms between the designer and the Amsterdam based owners of the brand, PVH, with the then-CEO claiming that his vision, though critically acclaimed, was “too fashion-forward for our core consumer.”

- In 2021, amid the global pandemic, Pieter was named creative director at Alaïa, the first designer to take on the mantle following the death of Azzedine Alaïa in 2017.

- Gesamtkunstwerk, the German phrase for a ‘total work of art’, is one that embraces a variety of artistic disciplines and forms. In Raf’s case, the term easily correlates to the melee of music, nightlife, art, youth culture and, of course, clothes that make up his era-defining fashion practice.

Credits

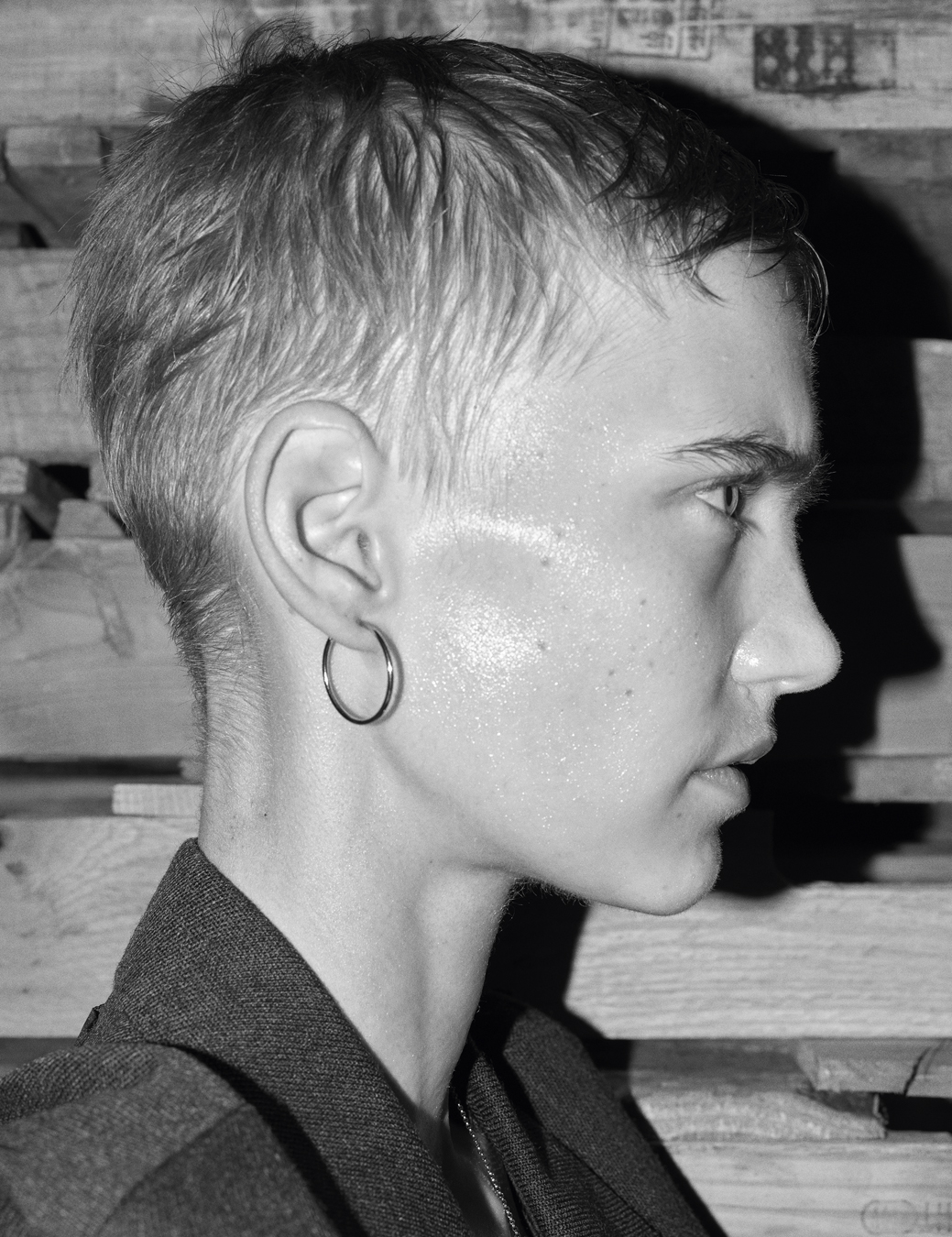

Studio photography Mario Sorrenti

Backstage photography Nick Waplington

Fashion Alastair McKimm

Hair Tomo Jidai at Home Agency using Oribe

Make-up Kanako Takase at Streeters using Addiction Beauty

Nail technician Honey at Exposure NY using Londontown Perfecting Nail Veil

Prop stylist Peter Klein at Frank Reps

Photography assistance Kotaro Kawashima, Javier Villegas and Brett Ross

Digital technician Chad Meyer

Fashion assistance Madison Matusich and Jermaine Daley

Hair assistance Kayo Fujita and Alexandra Diroma

Make-up assistance Anna Kurihara and Miki Ishikura

Prop assistance Melanie Chambers and Joe Arai

Production Katie Fash and Layla Néméjanski

On set production Steve Sutton

Production assistance William Cipos and Pickle

Casting director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING

Casting assistance Brandon Contreras

Models Luna Passos, Binx Walton and Selena Forrest at Next, He Cong at IMG, Mariacarla Boscono and Wali Deutsch at Women, Mahault Cerfontaine and Ilias Loopmans at Rapture, Julia Nobis at DNA, Gendai Funato at The Claw, Saunders at Elite, Ilya Vermeulen at Platform, Sora Choi at The Lions, Victoria Fawole at The Industry, Anok Yai at No Smoking Period, Hunter Pifer at Q Management, Diane Chiu at Ford

All clothing, accessories, necklaces and shoes RAF SIMONS

Earrings (worn throughout) stylist’s studio