This article originally appeared on i-D Japan.

Ginza, Shibuya, Aoyama, Naka-Meguro, Shinjuku, Harajuku — each of Tokyo’s centers of style has its own distinct flavor of fashion. And without question, it’s Harajuku alone that has given birth to the most exciting explorations in style in the metropolis. Certain spots in the capital are bases of creation, and some of consumption; the different areas are connected together like the organs of a body, and their distinctive roles in the organism that is Tokyo are just as distinct.

Harajuku is a tiny wellspring of fashion creativity. The district’s creations travel downstream from their source, making their way throughout the city, and their influence eventually ripples out across the entire world. And, at the risk of straining the metaphor, it might not be going too far to say that for the true lovers of the little precinct, the cool kids of Harajuku are like little fairies flitting around the fountainhead. A common thread in conversation of late has been the perceived demise of the area. Commentators ponder the stability of Harajuku’s hitherto unchallenged reign, and complaints like: “there are so many people, but barely anyone cool,” and “this place is starting to look just like everywhere else!” have practically become the go-to greeting on the streets. Safe to say, it’s rare for so many to be so concerned about the fashion trends of a couple of city blocks.

One of the biggest reasons for the closure of FRUiTS in its magazine form last December was the thinning numbers of these “fairies.” It’s been hard just managing to take enough photos to push out a new edition each month, and we refused to make compromises and publish boring photos, so we simply decided to give up on publishing it in a monthly form. Instead, we plan to periodically release new editions whenever we have collected enough photos to amount to something worthwhile.

But this “Harajuku style” hasn’t always been a thing. It might sound like ancient history now, but it’s only been about 20 years since the phenomenon suddenly burst into life. Harajuku had long been a stylish place, but it wasn’t really a hotbed of original styles. It was actually rare for original fashions to arise from the streets at all — anywhere in the world. Besides London’s punk scene and the hip-hop and skater fashions of America, nothing else comes to mind.

Before the birth of Harajuku fashion, Japan had been under the decade-long reign of the “DC brand boom” of Comme des Garçons and Yohji Yamamoto. The style’s influence reached across the world, and Harajuku, too, was naturally under its spell. Before even that, the only big trends in Japan were established by the major apparel companies, such as the Hamatora and Bodycon styles, and adaptations of slightly outdated fashions from abroad. Men’s fashion more or less consisted of the Ivy League-inspired VAN and the European stylings of JUN — or at least, as far as I recall. I don’t really remember what kind of clothes I used to buy back then.

Tokyo fashion entered a somewhat aimless period for about two years following the fervent years of the DC brand boom. Vivienne Westwood imports and Christopher Nemeth, who’d just moved from London to Harajuku, were the hottest thing in those days. Tra I Venti and Beauty:Beast from Osaka were trying to break into the Tokyo scene. There weren’t any particularly big trends, and the capital’s styles all seemed to be heading in different directions. I personally enjoyed that variety, though; it felt as eclectic as the vibrant street fashion scene of London.

And that’s when Harajuku fashion as we know it today suddenly reared its head: it was 1996 when the kids hanging out in Harajuku took their fashion into their own hands. It doesn’t seem all that unusual these days, but back then that’s really not how fashion worked. Fashions were just trends made up by designers, brands, and magazines, and “fashion sense” was simply what you called it when people chose which ones to adopt. Regular people had never really made up their own styles. And Harajuku’s influence reached further than just Japan. It affected fashion across the globe.

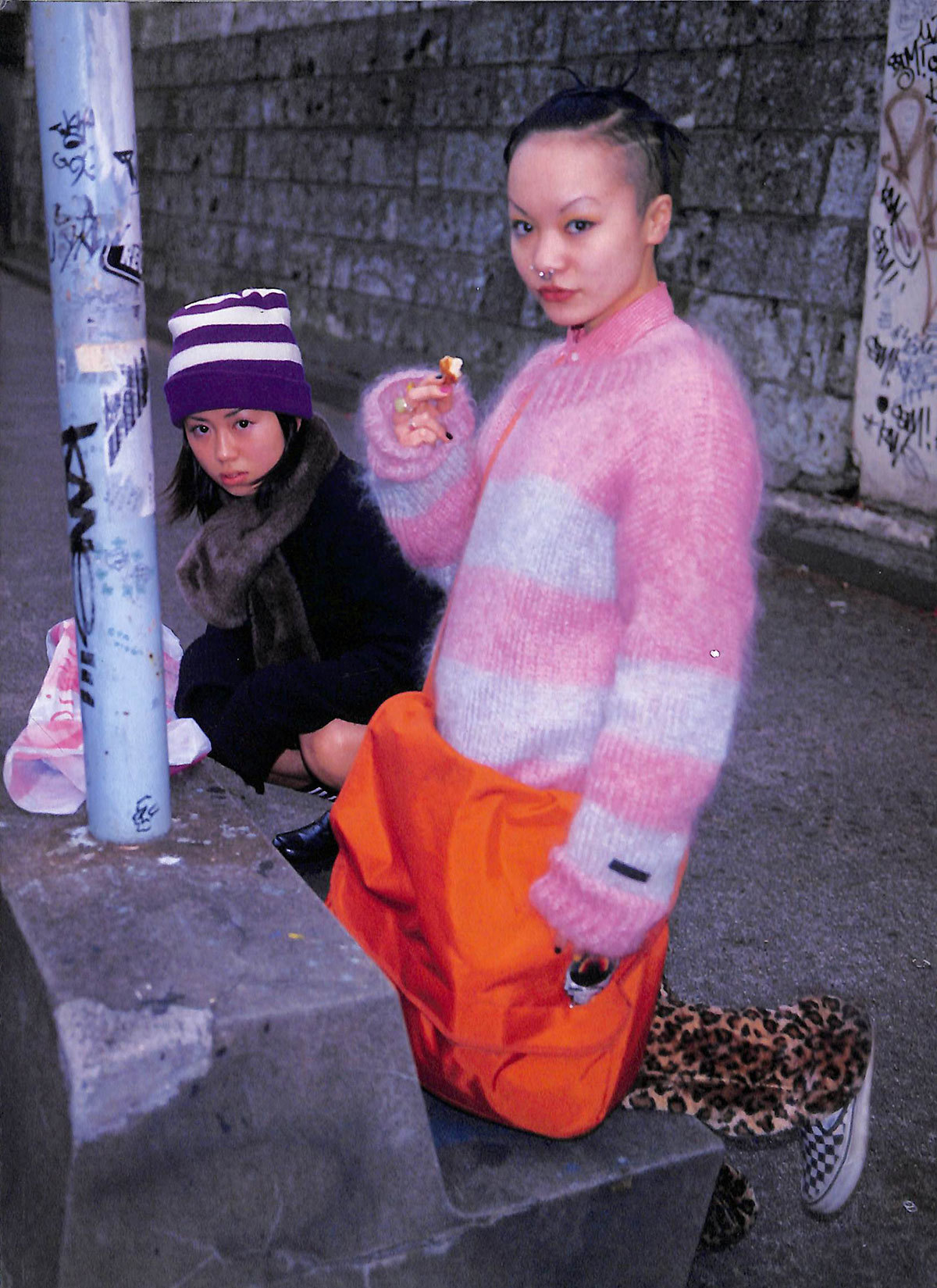

It was photographing these two girls (pictured above) for STREET Magazine that made me decide to start a magazine of nothing but Harajuku street shots. They were friends going to different schools: the one in the pink sweater was a student at the Nippon Beauty Academy. Her whole look was amazing, with a nose ring, a unique hairstyle, and an oversize pink Milkboy knit over a pink button-down shirt. It was the perfect combination of cuteness and strength, and I was really impressed by her self-confidence and unique style. Later on, she just happened to be the first person I photographed when I started shooting for FRUiTS. She was wearing a tartan check coat by Milkboy, hanging about in the pedestrian zone in Omotesando. I didn’t realize it was the same girl as before, and she looked a bit scary, so I actually got my assistant to ask her if it was OK to take a photo! She didn’t pull a pose or smile when I raised the camera. She just stood there staring directly into the lens, and that eventually turned out to be the way people usually posed for FRUiTS. When I asked her about her rather tight coat, she told me she’d cut it and taken it in herself. Later on, she started attaching little plastic accessories to her jerseys, starting a style that would eventually lead to the Decora trend.

These two were students at Bunka Fashion College. The girl on the left is wearing a mix of two traditional Japanese pieces of clothing — a haori overcoat and setta sandals — but I’d never seen anything like her style before then. It was something that a few kids just started wearing all of a sudden back then. She was wearing a sports jersey under her coat, too! It was such a perfectly mismatched combination. I’d also never seen anything like the yellow hair on the girl on the right… let alone coordinated with a pair of sneakers. I was convinced that Harajuku’s kids were doing something entirely new and unique. It was the start of a Japanese fashion revolution.

Following that, new trends hit the streets of Harajuku every three months. All it took was for a few pioneers to start doing something new, and before you knew it everyone else was getting in on it too. And then, of course, the pioneers hated to be caught up in a trend, so they did something else to get away from it again. Then a couple of talented new trend-setters would emerge from the crowds and start doing their own thing. The whole chain of events acted like an evolutionary system. It was also about that time that people started making second-hand clothing cool, and a year later Decora would emerge as a pinnacle of that evolution. That’s when the Hokoten pedestrianized zone closed down, which was a really significant event. The guys were all into Urahara fashion at the time, and the girls were going through what was called the “Simple Boom.” I personally consider those days the Dark Ages of Harajuku, but looking back on it the level of fashion back then was actually very high. After five years of that, Kyary Pamyu Pamyu burst onto the scene and it looked like Harajuku fashion was tentatively making a comeback, but recently we’ve been falling back into a serious slump.

Harajuku’s fashion comes in waves. It gets better, and then it gets worse. But since the closing of the pedestrian zone in 1999, the waves have been steadily getting weaker and weaker. The loss of Hokoten was like a shot to the gut. If a street is dedicated exclusively to consumption, then it’s fine to have it open to cars, but the budding flowers of creativity need space to grow. Hokoten was Harajuku’s car-free zone, a kind of town square-like place where people could just wander around and hang out with their friends, and it was the perfect environment to allow the district’s unique fashion to come to life.

Smartphones and social networks are also no doubt partly to blame for our current slump. People can easily fulfill their desire for acknowledgement with a post online, and it doesn’t cost a thing. Fast fashion has also played a major role. It’s the very model of destructive innovation; while the average level of fashion has risen, it’s been almost entirely homogenized.

But the power of fashion will be discovered again. I don’t know why, but Japanese kids just have a fantastic sense of style. Genius young fashion prodigies will rise up again, and all the adults can do is allow them the environment they need. There’s a lot that needs to be done, but the return of Harajuku must start with the restoration of Hokoten.

Credits

Text Shoichi Aoki