Darren Aronofsky does not have a reputation as the easiest of men. His films are gnarly, either because of the viscerally wrought suffering (Requiem for a Dream, Black Swan), grandiose existential sweep (The Fountain, Noah) or both (hello Mother!). It’s a surprise, then, to find him positively zen-like, both warm and open to challenging questions about The Whale, his adaptation of Samuel D. Hunter’s play about a 600lb online college professor eating himself to death in response to a tragedy.

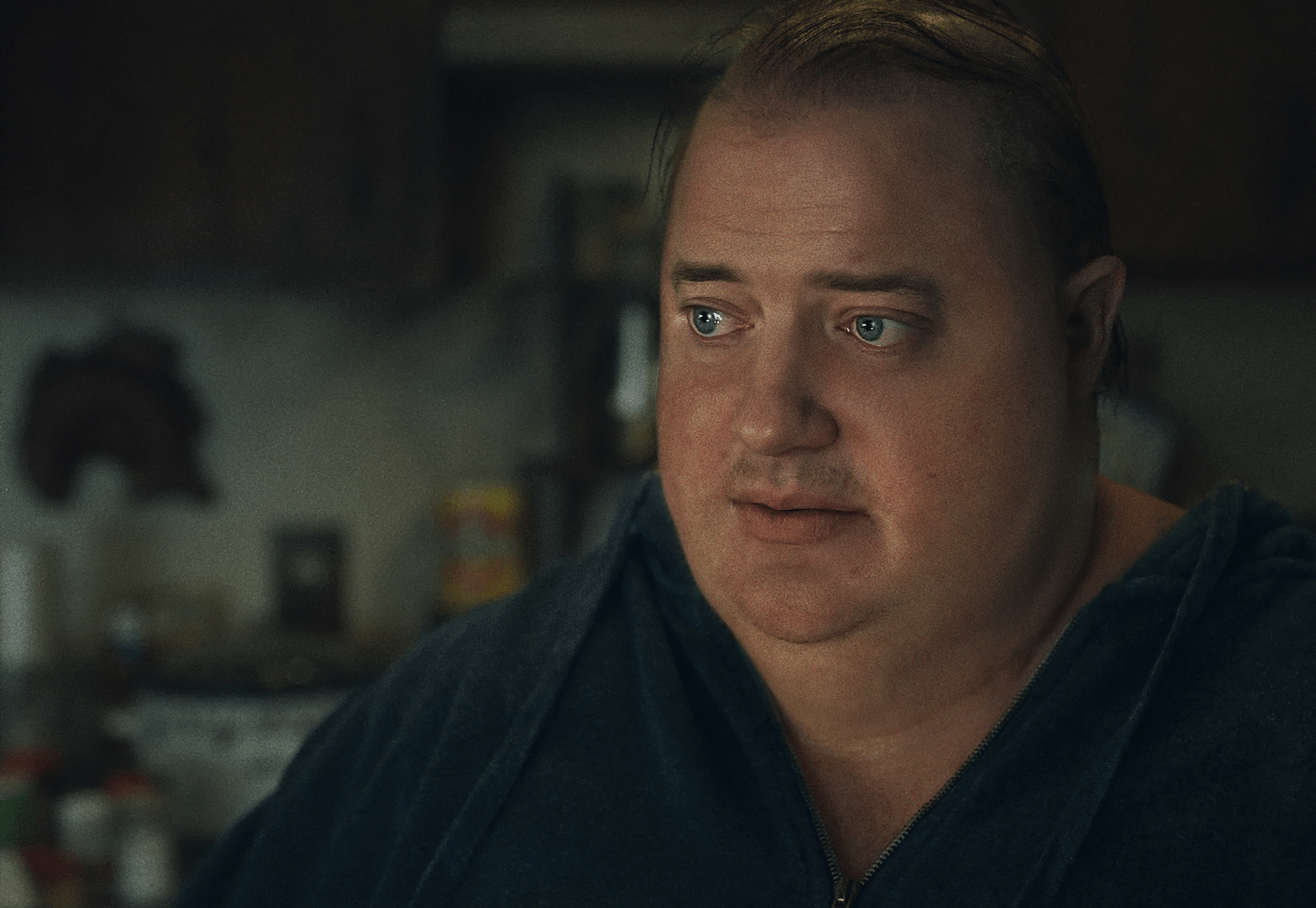

It’s a film that has garnered both buzz and controversy since it premiered at Venice Film Festival last September. Although there has been a rapturous reception for Brendan Fraser’s performance as the college professor, named Charlie, some critics have responded to his character with open fatphobia. (Variety’s review compared him to Star Wars villain Jabba The Hutt.) On the other end of the spectrum, Aronofsky has been accused of everything from gawping at his lead character to denying a 600lb actor a role by casting Brendan Fraser in a prosthetic suit instead.

More than anything, The Whale is a deeply emotional account of a man striving for redemption in the days before he dies, specifically reconnecting with his estranged daughter Ellie, played by a furious Sadie Sink. Scenes of exquisite and complex intimacy unfold as nurse Liz, played by the sensational Hong Chau, cares for him, enabling his eating disorder while an unsolicited missionary, played by Ty Simpkins, tries to save Charlie’s soul.

Aronofsky is game to go pretty much anywhere, speaking in slow and considered detail, philosophising on the nature of being. Here, he discusses our need for tragedy, working with the Obesity Action Coalition, performance as a divine expression of the soul and what he has coming up next.

There’s a poem by Mary Oliver called “The Fourth Sign of the Zodiac”. It contains a question that I wanted to put to you: Do you need a little darkness to get you going?

To see the stars, the world needs to be dark because it’s all about contrast, always. I have nieces who I just was having a conversation with. [I was saying], one thing you learn as you get older is that life is this roller coaster, and the dark times make you better able to appreciate the light times. If it was always light, there would be no happiness. There was a great Twilight Zone episode about that. A guy wakes up after he dies and everything’s perfect and suddenly the fun of life is gone.

The dark enables you to see the light if you make it through. But not everyone does, do they?

One of the big cultural problems right now is that the form of tragedy has been removed and wiped out of popular entertainment to a large part. The so-called ‘Hollywood ending‘ is largely responsible for that, and even things like Instagram paint this fantasy that is completely unattainable by most people and doesn’t have its feet rooted in reality. So everything about how marriage is portrayed, how lives are portrayed, how death is portrayed, is done in this very easy way. What tragedy teaches us is that by experiencing it in the theatre, or up on the screen, you live vicariously through it. You don’t need to go to those dark places to have those feelings, but by having those feelings they allow you to be more human, and to be more honest and truthful about where you are in the world.

It mitigates the loneliness of suffering.

That too. The reality is, every single human on the planet is filled with all different shades of black and white and grey. That’s what makes us people, but that’s not taught, and it’s not what we see in most films. They try to put in a little bit, like, Iron Man will have a few moments of self doubt. But that’s about as far as it goes. Even Batman, you know, who is this superhero that’s supposed to be dark — it’s just dark in terms of how cruel he’s going to be. But it never talks about his own self doubts and his own real unhappiness, and that’s interesting for characters.

Is that what you would have delved into for your Batman? [In the mid-00s, Aronofsky was hired by Warner Brothers to adapt Batman: Year One and got as far as co-writing a script with Frank Miller.]

I have no idea. That was a very long time ago. I never really got that deep into it to think about it that hard.

So you’re not haunted by past projects?

Yeah, I’m only haunted by past projects that I still may do because they’re floating around and I’m trying to figure out how to get them done.

Can you tell me a little about the Obesity Action Coalition and what their role was on The Whale?

Very early on, when we started working on the film, we got involved with the OAC, which is a group that has chapters, at least in America and Canada. They are a coalition that tries to help with all different types of challenges that people living with obesity may encounter, as well as helping their families, and promoting the same messages as the movie: ‘Don’t judge a book from its cover.’ and ‘There are real people here.’ With all these different people watching the movie and some of the reactions coming out, I noticed that the prejudice against people living with obesity is so deep. There are tons of scientific studies that show how people living with obesity don’t get the same access to the same type of healthcare and are often seen as lesser and not as intelligent. Their portrayal in fiction films is often the butt of jokes; in reality TV, they’re incredibly exploited. So the OAC were very supportive about having this story told about a real human being. When you say that, of course, every single person living with obesity is a real human being. But they’re so often not treated that way.

So were they a script consultant?

We had them look at the script and they talked about sensitivities that we should be aware of. I’m sure they’ve had some impact on us and how we approached certain things. They were excited throughout the entire process, and when they eventually saw the film, they were really supportive. They’re glad it’s out there.

As a character piece, it’s so clearly empathetic, but there have been criticisms of the visual language. One critic said that the way that Charlie is framed when he rises from the couch is the same way that Steven Spielberg framed the tyrannosaurus rex in Jurassic Park.

That is as much of the person watching it as anything. The character is standing up and the camera’s tilting up. The character is a big man. People are bringing what they see into this in a lot of ways and so there’s not much I can do. There were no digital effects, but the fact that people are seeing a monster… That is what we’re confronting. When people see Charlie for the first time, they are going to have all different types of prejudices about him. But the two hours you spend with Charlie will break your heart if you allow yourself to go in through those beautiful Brendan Fraser eyes, and that’s what the film is. But yes, there are constant reminders throughout the film of how we, the audience, generally see these people.

There’s not much to the camerawork in the film, it’s basically just watching the action. If suddenly your mind goes to ‘Oh, it’s like a dinosaur movie or a monster movie.’ Is that me? Or is that what you’re bringing? Hopefully, even if that’s what you’re seeing, spending time with him will allow you to see through the surface to the man.

Is there not a cynicism to assuming that every audience member’s entry point is to judge him in that way?

I’m being realistic having worked with the OAC and understanding how people like that move through the world. I also looked at a deep, deep ream of scientific evidence that people who show up to hospital with obesity are not given the same treatment and judged that it’s their fault. There was a recent thing in the New York Times about how many of us think that people who live with obesity are subpar. I’ve gotten so many texts from doctors that have seen the film who are like: “Guilty as charged”. They said watching this movie is going to change the way they practise medicine because they have met someone like Charlie and now realise that their prejudices may be completely inaccurate. Because Charlie is a man of letters, he’s a great intellect. And that’s not something you would ever expect.

A scene that rang very true to me, as I used to have bulimia, was the one near the end where Charlie is bingeing and it’s clearly an emotional response. Can you talk about creating that scene?

It’s interesting how deeply people are affected by it. It was always obvious to Sam [Samuel D Hunter], and it was in the script, that we would have to demonstrate Charlie’s emotional connection to food because that’s a big part of who he is as a character. It’s not like he’s so out of control. There’s literally three shots. One where he’s eating two slices of pizza on top of each other. Another one where he’s mixing some food. I guess it’s the mixture of food that’s shocking to people. What’s going on there is people, at this point, really care about Charlie, and it’s really hard to see someone hurt themselves.

You’ve said [to the LA Times] that the moments on set between “action” and “cut” are “sacred” and “like church”. I was curious to unpack what you mean exactly by that.

We do all of this work as filmmakers to get to that moment. The only time we’re in the deep creative mode is between “action” and “cut”. The rest of the time, we’re doing a lot of planning, a lot of imagining. When we’re the closest to our compatriots in the art forms of dance or music — who are truly doing art in the moment — is between “action” and “cut”. It’s when actors are channelling their instruments and all the other filmmakers around them — the people collecting the sound, the people lighting, the people doing hair and makeup — everyone is focused on trying to create this eternal moment in motion pictures.

In your work, there seems to be a through-line where you put a character that you love in cruel circumstances.

I don’t know if I ever really love any of my characters… just teasing! If you think about it, most movies stick their heroes through challenges. I up the volume a bit to try to represent things in realistic ways. That’s because I choose characters whose stories generally either start or end up in very extreme places.

Looking to the future, do you have any updates on Adrift, and the Black Swan musical?

Adrift is just a development deal. We’re developing it as a screenplay right now. Black Swan the musical is being worked on. There’s some beautiful music and incredible choreography, and it’s slowly but surely coming together.

Is it true that there’s a project you’ve been sitting on for 22 years?

That’s true, you did your research.

Can you give us a clue about it?

No, not really yet. Sorry. I hate giving away too much. But it’s something I’ve been working on since I first read the script, back when I was editing Requiem for a Dream. Hopefully we’ll figure out a way to get it done.