This story originally appeared in i-D’s The New Wave Issue, no. 373, Fall/Winter 2023. Order your copy here.

“You are flying, travelling, over water and over land through these insane jungles that have been evolving as the life force of the planet over tens of millions of years,” James Deutsher, one half of the Australian duo who established biodiversity foundation DEEP, begins to describe an aeroplane trip that changed his life. It was on this journey—a long, arduous quest out to the middle of the Amazon rainforest —that James began to think that his work as an artist, curator and designer was perhaps not what he was put on this Earth to do. Around the same time, back in Milan where the pair now live, Clea Irving was having similar thoughts while working for Nike, leading collaborative projects with heavyweight designers like Virgil Abloh and Matthew Williams between her home city and Paris. This was in 2019 and, by 2020, the two had joined forces to formulate their budding ideas on how to change the world into the multifaceted biodiversity foundation DEEP.

At its core, DEEP’s mission is to act as a “radical biodiversity infrastructure”, a phrase which appears in most of their press and branding. This may sound nebulous on first reading but, when you take each word individually, a map begins to appear indicating what the foundation does and how they actually go about doing it. ‘Biodiversity’ is core to the project, and for DEEP, supporting biologically important areas across the world is their raison d’être. To do this, they partner with local organisations working on the ground throughout the globe to assist in gathering vital data, support existing ecologies in each location and facilitate rewilding and educational programs to help those organisations grow.

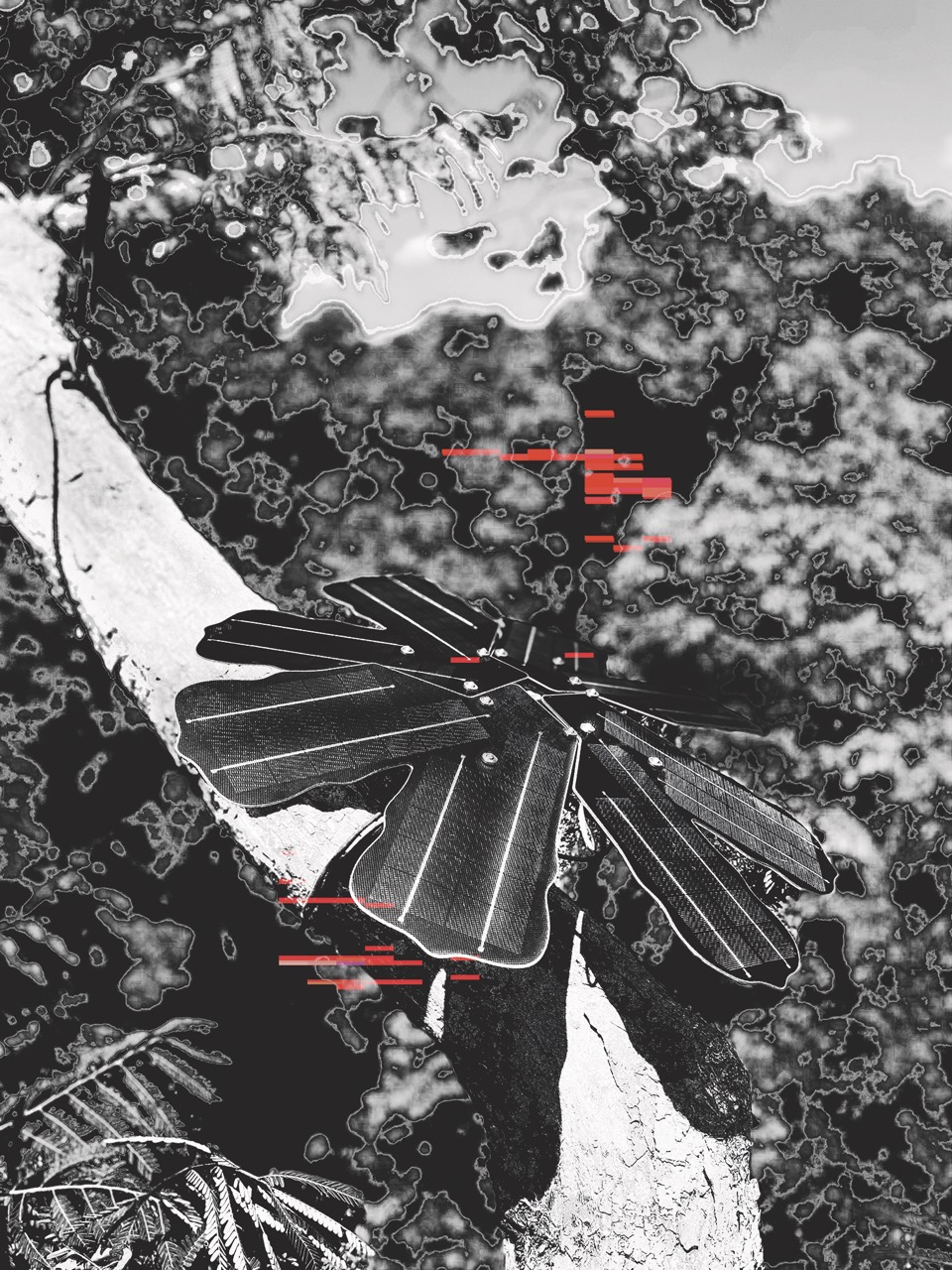

Then we have ‘infrastructure’: that stuff that provides the framework for our lives, such as the roads, buildings and systems that allow us to function within urban spaces. But there are infrastructures in the wild, too: the complex ecological systems which are our planet’s vital force. Responding to this, DEEP have formed their own specific set of infrastructures built in collaboration with some of the world’s most exciting design projects, such as Armature Globale’s climate-shock resistant shelter to house the endangered white-clawed crayfish which will be installed by DEEP and Rewilding Apennines, their partner organisation in the Italian Apennine mountain range, or Sabine Marcelis’ ongoing work designing insect shelters in collaboration with Projeto Mantis, a prototype of which will be deployed in the Amazon rainforest in November 2023.

Finally, and perhaps most important in distinguishing DEEP from other ecologically-focused foundations, we have this notion of ‘radicality’ which emerges through the two distinct parts of their operation. The first is the DEEP foundation, which is committed to working from the ground-up, partnering with local organisations to assist in ongoing grassroots biodiversity projects across the world using the essential expertise of local people. Then, we have the other facet of their work — DEEP Services — which employs a hacker mentality to accrue both awareness and cash for their work, using public-facing projects with global fashion and lifestyle brands to get their message out and partially fund their projects.

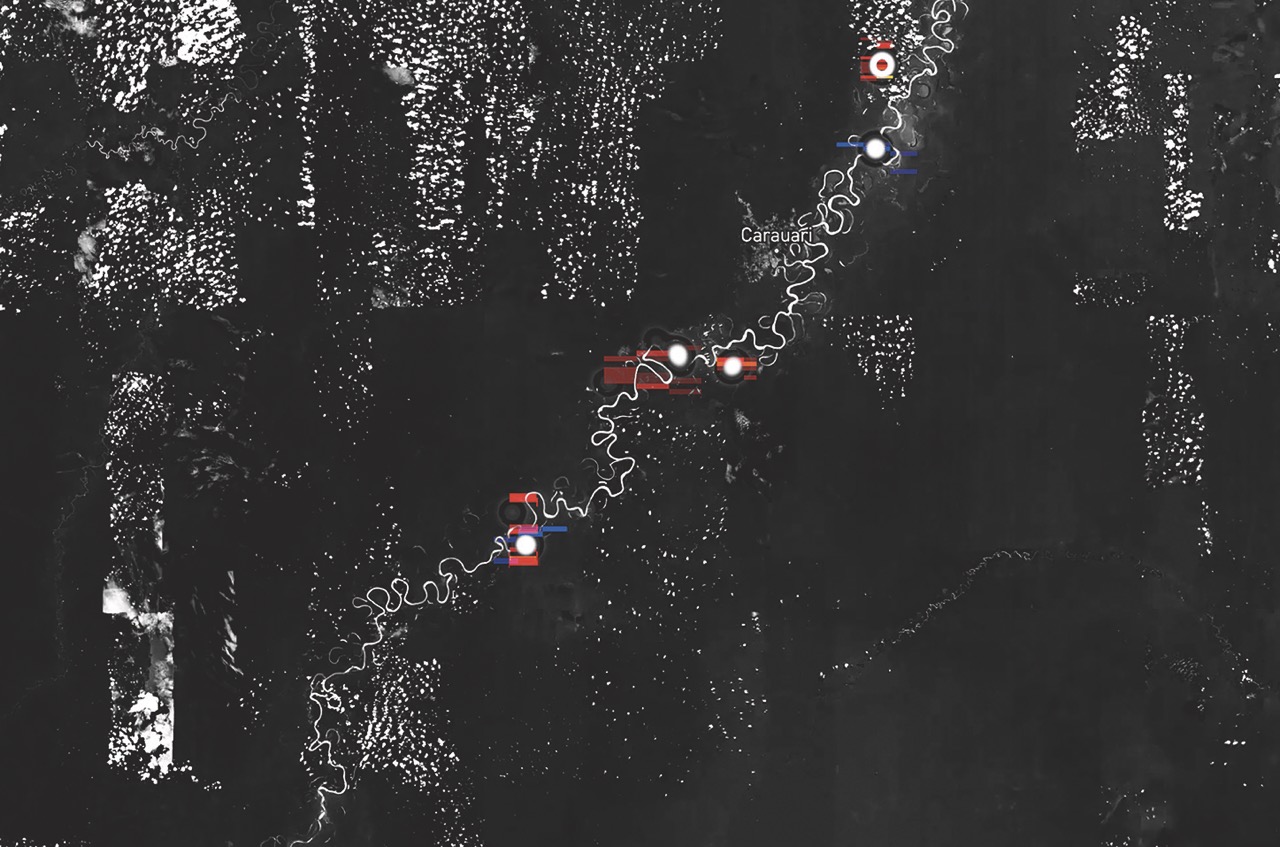

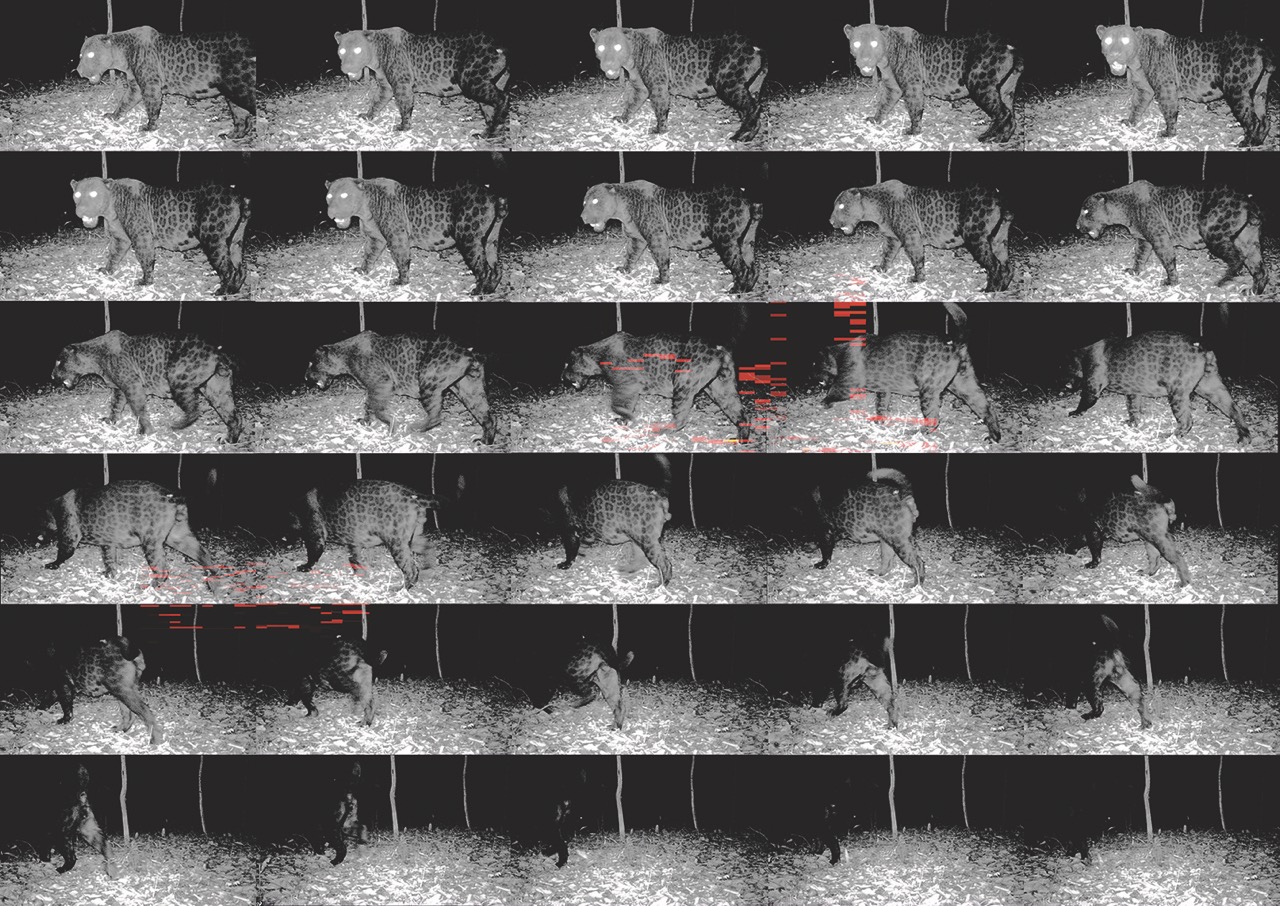

DEEP have produced short films directed by Ben Ditto and photographer Nick Sethi which both feature soundtracks created with audio adapted from recordings made by DEEP’s specially designed solar-powered bioacoustic monitors in the Amazon and Sumatran rainforests, by Varg2TM and Tzusing respectively. Other partners include Burberry and Salomon, the latter of which collaborated with DEEP to monitor the air quality at their flagship in Paris and, using specially designed monitors by Armature Globale, compare it with the air at Refuge du Montenvers in the French Alps. Initially aimed at Salomon’s existing trail running community, the results showed that the levels of pollution in Paris were approximately double that of the Alps. This conclusion is perhaps unsurprising but, considering the ongoing conversations around air pollution and health in major cities across the world, crucial data nonetheless.

It’s a symbiotic relationship, where brands can soak up DEEP’s cultural and social capital, whilst DEEP uses their paycheck to help fund the foundation’s ongoing work, as well as utilising the huge global platforms these brands have. So, here we find that we have the perfect example of what a “radical biodiversity infrastructure” truly is: DEEP’s ability to unite on-the-ground organisations in important biodiverse regions, large global brands and those working within art and design to collaborate, providing a radical alternative to what an ecological organisation is, or could be in the near future.

“We’re not a conservation organisation; we don’t want to conserve things as they are.” DEEP

“DEEP is hoping to do the work now, to come in as a bit of a Trojan Horse,” says Clea, alluding to their work with fashion brands. Working with major names in art and design is not something that most large ecological organisations have the ability to do, but DEEP’s creative network allows them to develop their own, more engaging approach, targeting an audience that most established wildlife organisations may never have.

“We’re not a conservation organisation; we don’t want to conserve things as they are,” James interjects when that much-used ecological term comes up. Importantly, it’s not ‘sustainability’ that they’re attempting to tackle either. Both these words suggest that we need to do our best to find ways to keep going, but it’s impossible to imagine a better world without making colossal changes to how we live our lives and treat our planet. DEEP wants to be part of that change, helping it sprout from the ground-up.

Anna Grassi, Founder and CEO, GR10K

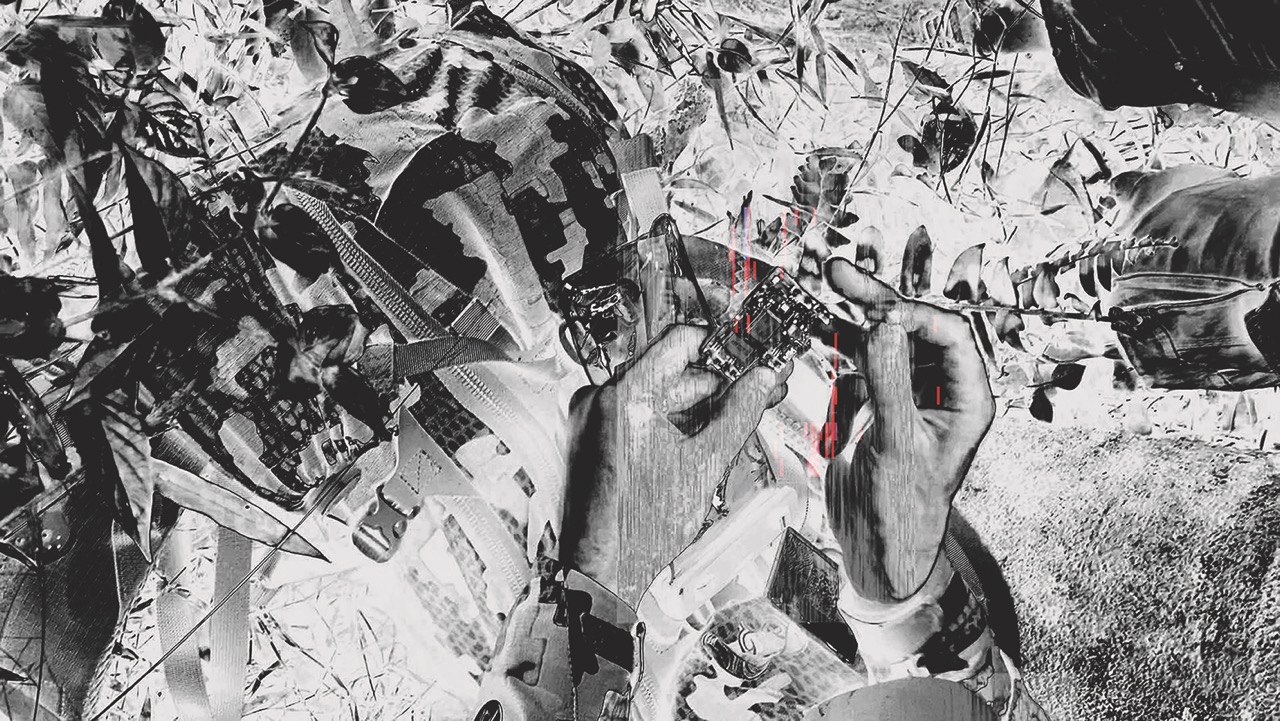

DEEP is working with Milan-based clothing brand GR10K to develop a hydro pack system. The system will carry aquatic monitoring sensors to support bio-surveys of Italy’s Central Apennines and the rewilding of freshwater ecosystems.

What does biodiversity mean to you?

GR10K taps into different ideas of ‘nature’ through the way collections are made and used. From researching the patterns of protective garments used by radical ecologist groups, to looking into American poacher culture, we try to lead our design method with a sense of contemporary urgency, and working with a project like DEEP fits into this approach. In this sense, biodiversity is a site of negotiation between many active agents.

Can you talk to us about embedding tactical functionality into radical design practice?

The integration of tactical features and technology in contemporary fashion design goes all the way back to the origins of garment design. We need to separate the fetishistic from the tactical, as today there are so many iterations of military-inspired design that may simply produce a reaction against such design. When it is too visible and explicit it stops working, it becomes a volatile aesthetic. If we approach the tactical as a pervasive technology of trust, between us and the endurance of our objects, practices and products we will be able to advance in many unforeseeable ways.

Hugo CM Costa, Co-Founder, Instituto Juruá

Hugo CM Costa is the Co-Founder and Scientific Research Coordinator for Instituto Juruá in the Western Brazilian Amazon. A biologist and doctoral student in Ecology at the National Institute for Amazon Research, Hugo has been working in Juruá since 2013 to promote community-led biodiversity outcomes. DEEP has partnered with Instituto Juruá on a range of activities, including AI-powered biodiversity surveys and fieldwork missions in the Amazon to prove that community-led ecosystem management directly supports increased biodiversity.

What does biodiversity mean to you?

In my role as an ecologist, I’m inclined to address this question using technical terms such as ‘species richness’, ‘species composition’, ‘abundance’ and ‘rarity’. However, I’d also like to express a more poetic perspective by likening biodiversity to music. In this analogy, species act as individual instruments, each contributing its unique intensity and melody, but when played together, they harmonise to create the beautiful symphony of life on Earth.

A community-led approach to impact is quickly becoming the new paradigm. Could you contextualise this approach in the Amazon?

Amazonia is probably one of the last frontiers to human knowledge. A complex socio-ecological system where we can still find an unknown organism or humans that have never interacted with the world the way we know it. However, it confronts a multitude of threats on various scales, including illegal mining, deforestation, land usurpation and the overexploitation of its natural resources. For decades, numerous foreign driven approaches to Amazonia’s development and conservation have faltered, primarily because they were imposed from a top- down perspective, disregarding the lives of millions of people who depend on the forest for their sustenance. Conversely, local indigenous and non-indigenous communities have coexisted with this environment for thousands of years. We firmly believe that Amazonia’s wealth in social capital, technology and solutions already exists within these communities. The Instituto Juruá’s mission is to shine a spotlight on community-led conservation initiatives that not only enhance the wellbeing of the residents but also safeguard the forest simultaneously.

Brigitte Baptiste, Director, Universidad Ean

Brigitte Baptiste is a Columbian cultural landscape ecologist, expert on environmental issues, icon for global biodiversity and a member of the DEEP Advisory Board. Brigitte considers ecology and queerness to be inherently linked.

What does biodiversity mean to you?

The amazing and endless expression of variety is constantly produced by organic processes, enriched by the cultural perspective of humans, made up of practices and symbols. Biodiversity is the ephemeral manifestation of the capacities of life to adapt and thrive through time and space in a permanent process of transformation called evolution. It means creativity and the joy of innovation, but is also an expression of endurance and beauty, though often hard to accept by us humans since it is based on the continuous destruction and reconstruction of everything.

What does the cutting edge of biodiversity research look like?

There are at least three main trends at the frontiers of biodiversity research. First, we still need to understand the complex relationships among species, adding complexity to our current ecological models. Second, we need to improve our models and scenarios for humans acting within that complexity in order to design the ecosystems of the future. Finally, we need to understand the connections between the molecular levels at which biodiversity works (genes) with their expression as bodies (organisms) thriving amidst living communities located in territories (habitats). But the most intriguing field of research is the cyborg connection: how our material and digital productions as humans become entangled with the rest of life on Earth, to care for it.

Sabine Marcelis, Founder, Studio Sabine Marcelis

Working as an independent designer within the fields of product, installation and spatial design with a strong focus on form, Sabine deploys a unique approach to empathy through design. DEEP is working with Studio Sabine Marcelis to design research enclosures for undiscovered insects to support biodiversity research in the world’s most remote ecosystems.

What does biodiversity mean to you?

Protecting and fostering all that is unique. We are on a scary path towards monocultures and protecting biodiversity is so important.

How do you approach design for non-human species?

It is quite different to how I usually design, where it’s very much from a personal fascination with materiality or playing with light. I recently designed a bee house and it was so much fun to learn about the behaviour of bees. That’s how I started that project—to learn as much as possible about their behaviour, preferences, risks, natural habitat and interactions with other beings to make something that works for them, but something that humans can also live with aesthetically.

Credits

Photography James Deutsher

Art Direction Remember You Were Made To Be Used