Vince Aletti’s handsome new book, The Drawer, has arrived. It gifts us, for the first time ever, a glimpse into his Aladdin’s cave of a flat file — or, more specifically, one of its drawers, stacked with constellations of pages the obsessed collector has torn from the tens of thousands of books and magazines he has amassed over four decades. Tearing, Vince reminds me from his packed-to-the-brim East Village apartment, has been a proclivity of his ever since he sheared the cover of the Harper’s Bazaar April 1965 issue — featuring a futuristic Jean Shrimpton in a pink space helmet — and pinned it on the wall of his dorm room. “I used that image to claim my space in a lot of rented rooms before I graduated from Antioch and settled down,” Vince says. “It hasn’t lost its iconic power for me.”

The Drawer was borne out of a moment of pure serendipity. “I pulled out a particular drawer to look for something when Bruno Ceschel, the genius behind Self Publish, Be Happy, was here,” he says. “He got curious about its contents. So, I started shuffling pictures around, as I often do when I put more pictures in that box-like space, and we loved the effect of images from all different periods and in many different styles. This was when the idea of photographing the contents of the drawer came about.”

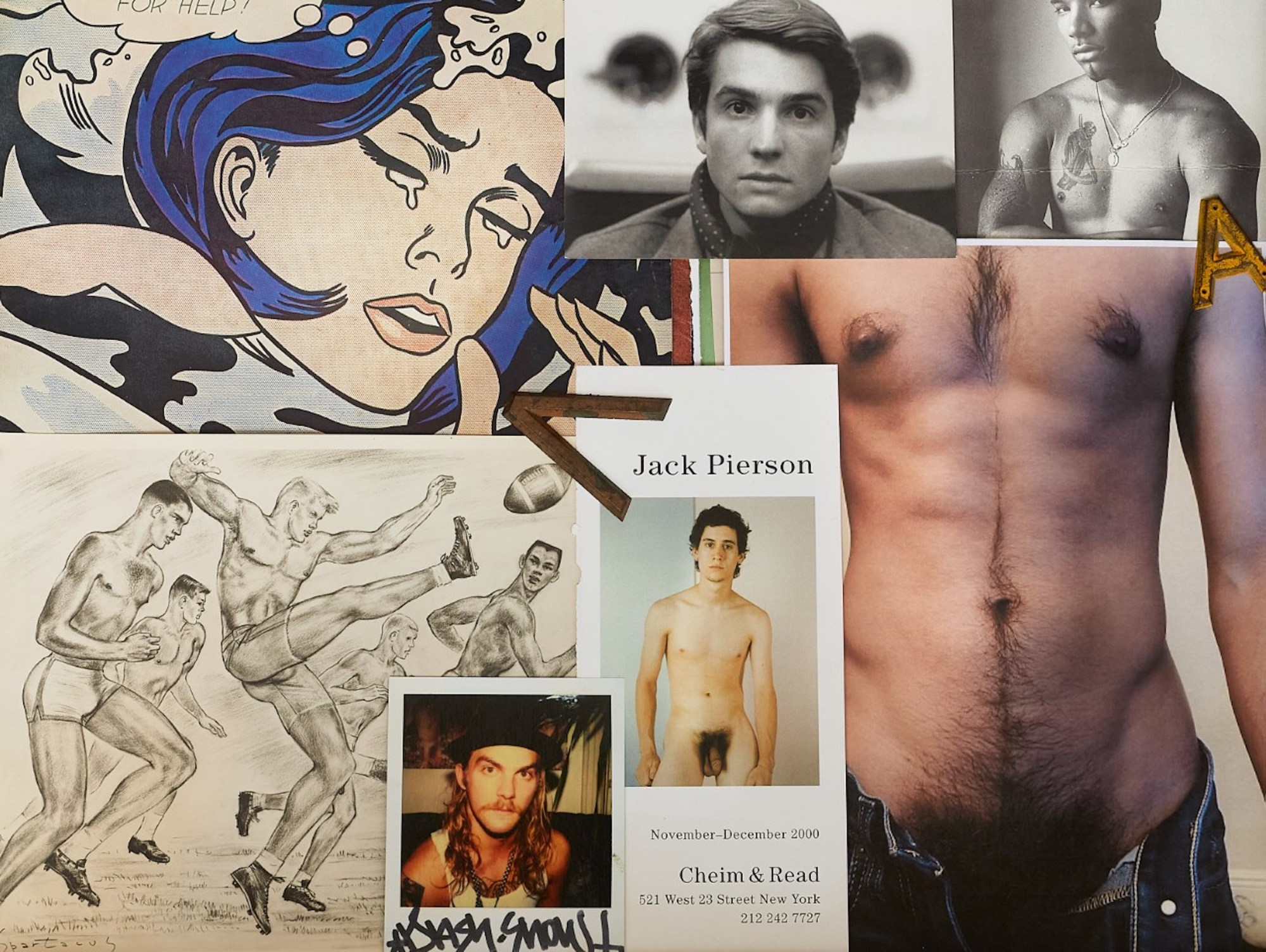

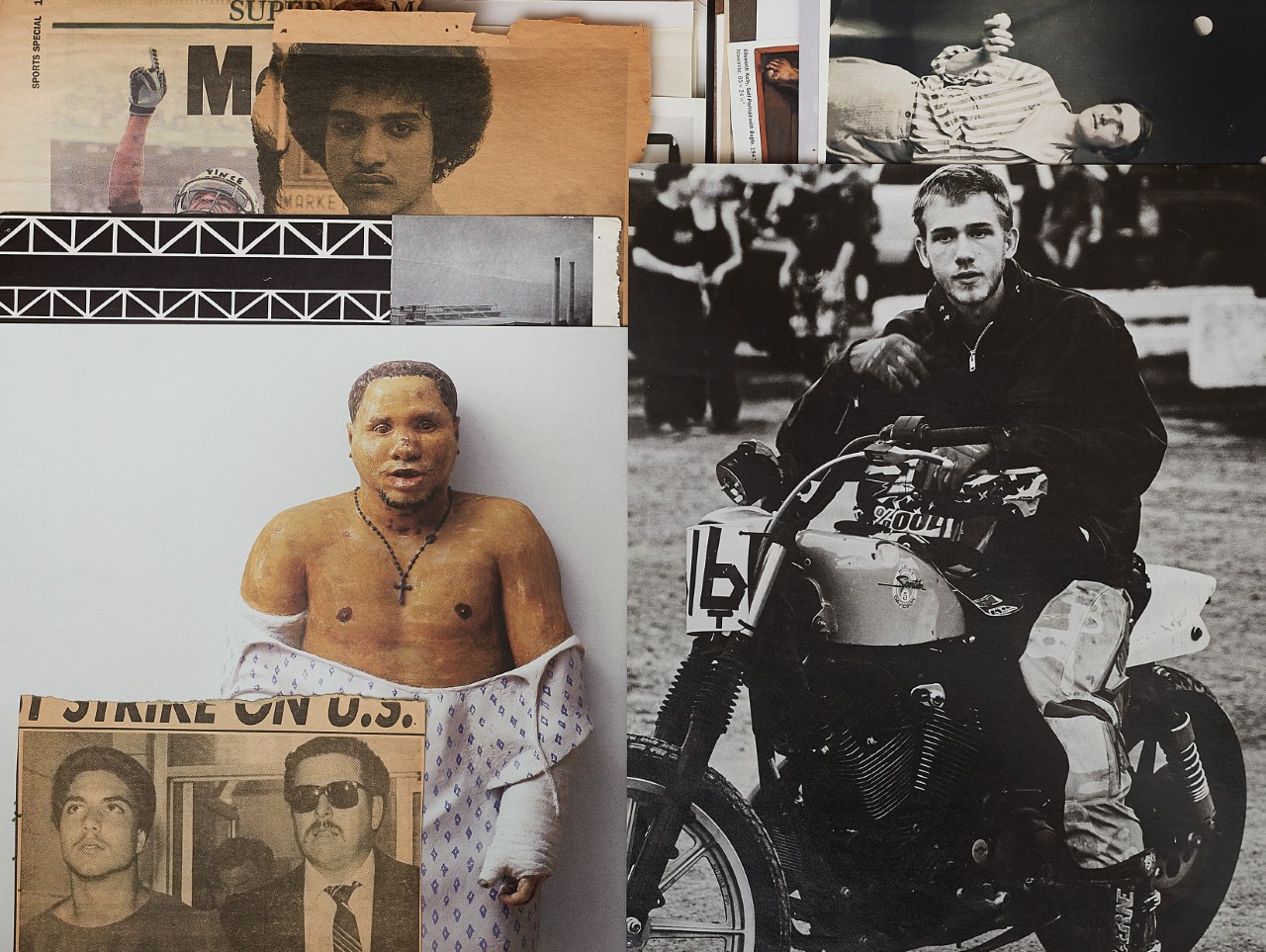

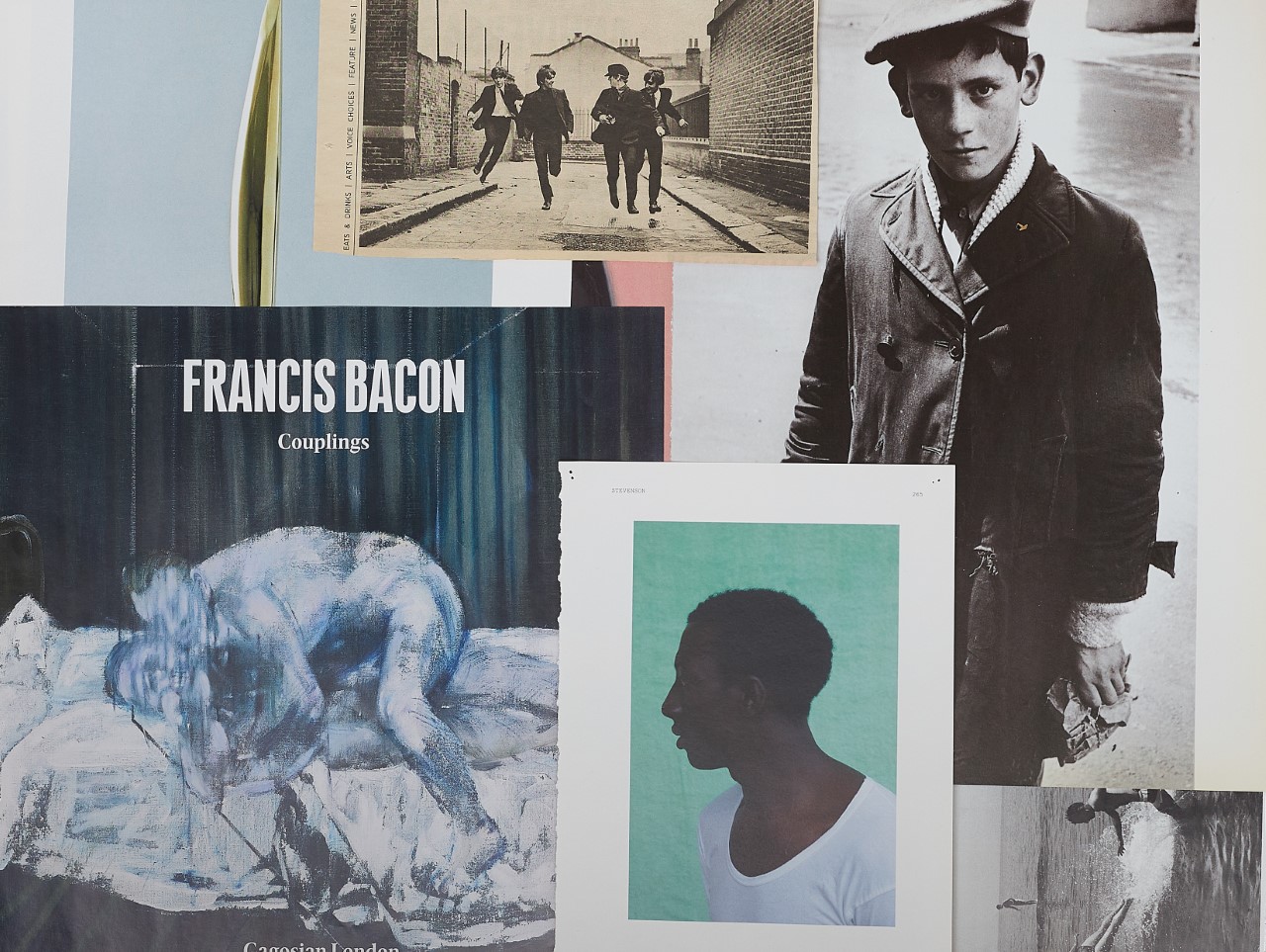

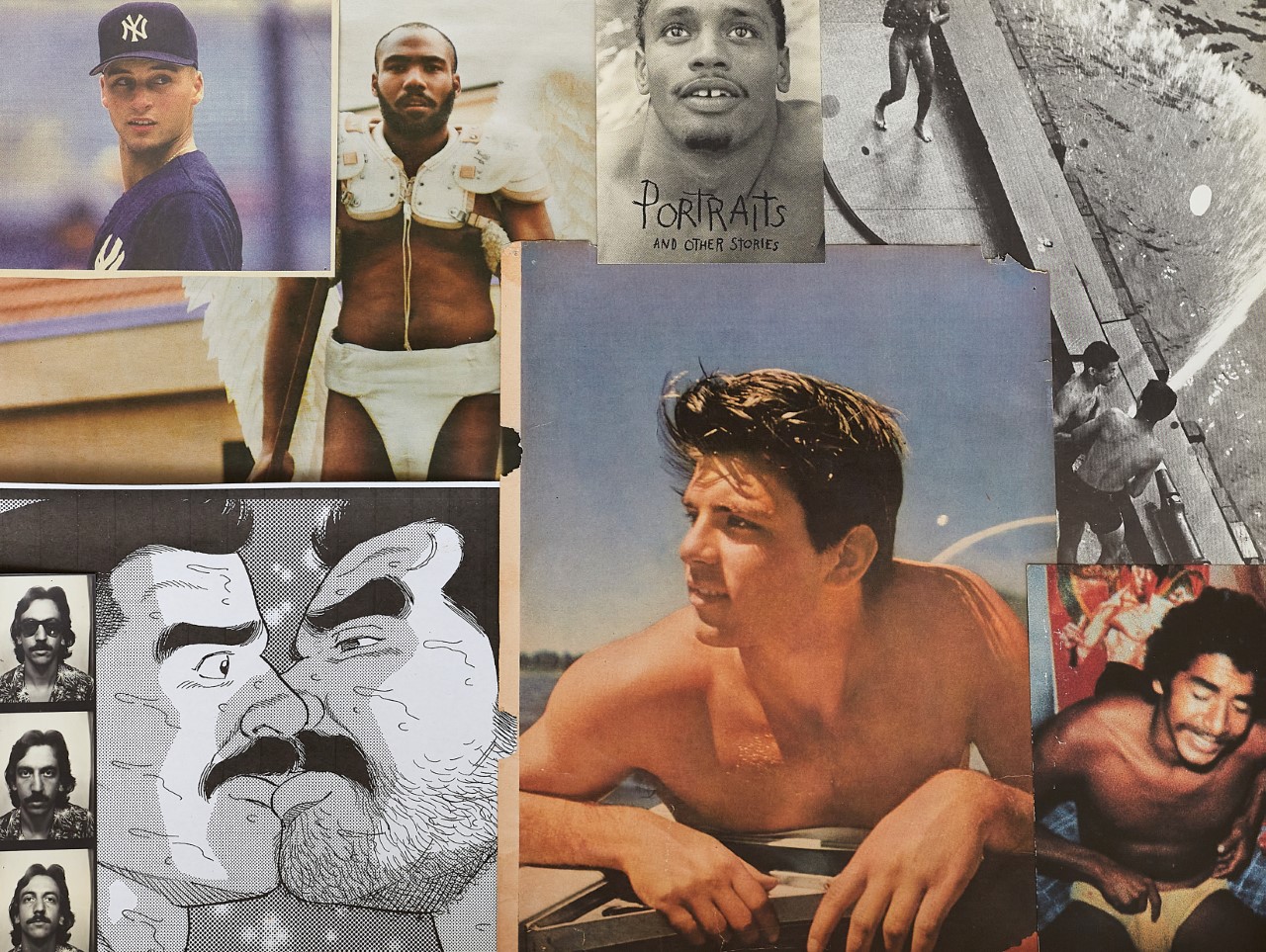

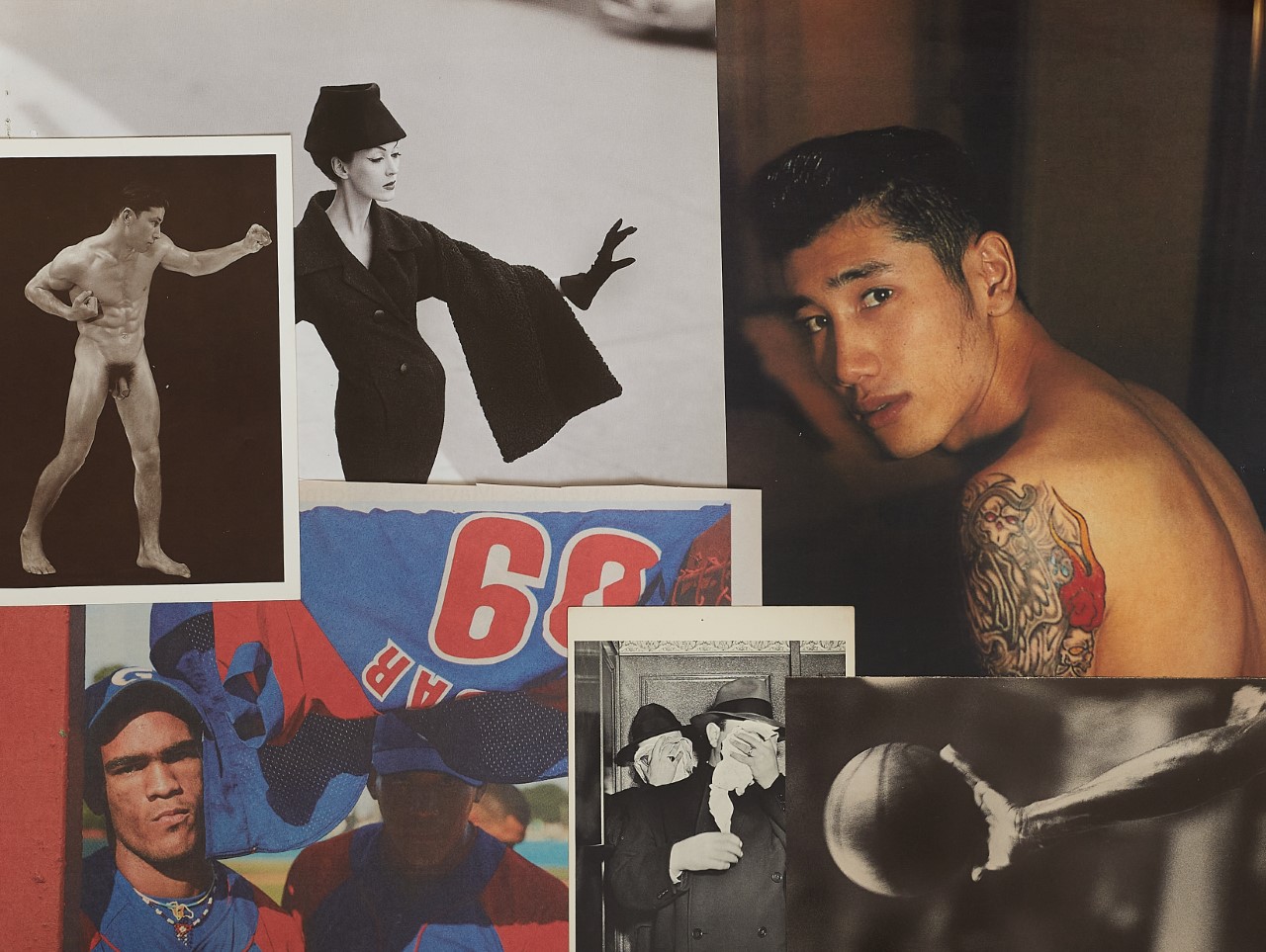

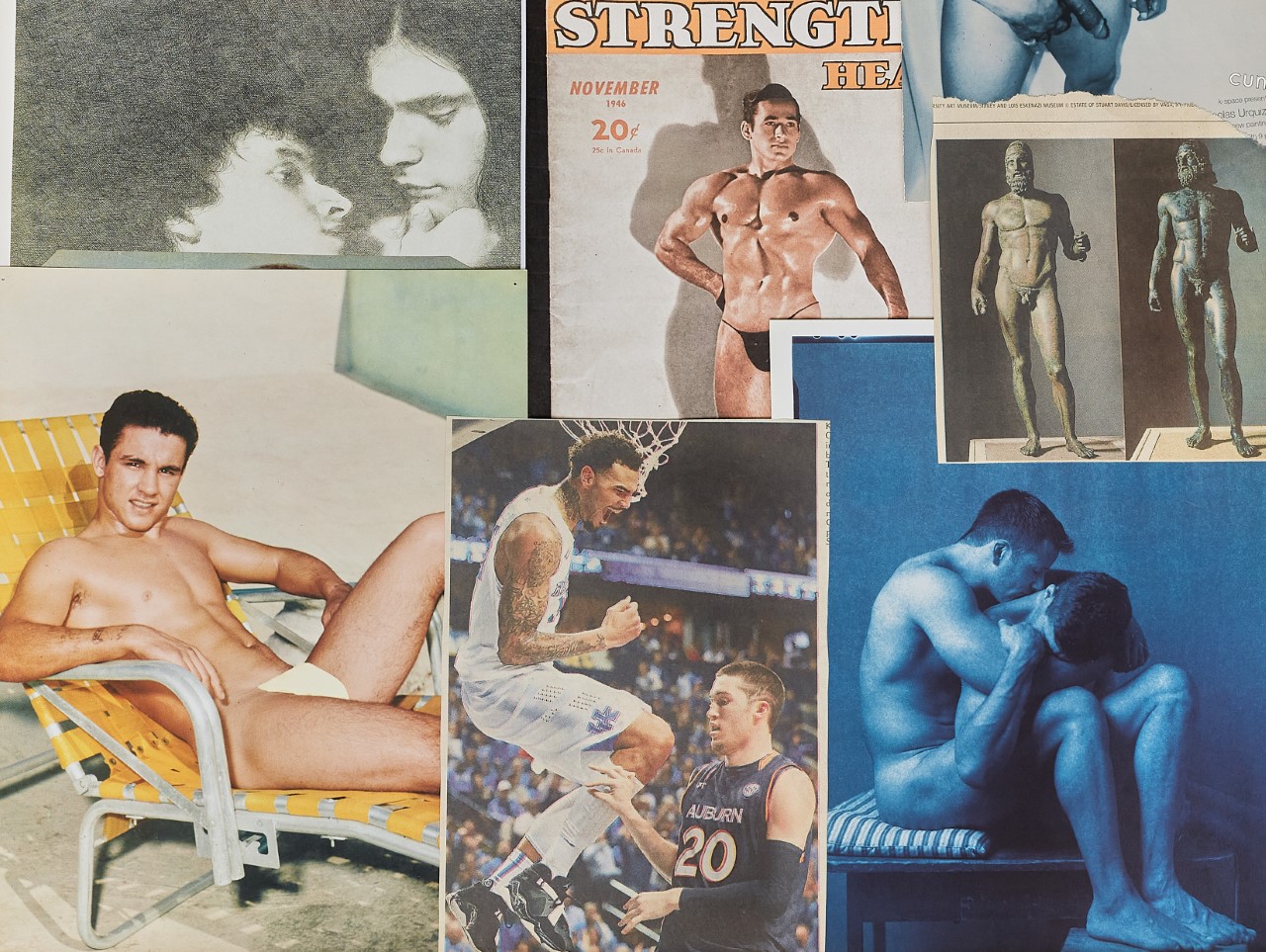

Flexing a kaleidoscope of genres, eras and subjects, all juxtaposed and overlapped with rhythmic intuition, The Drawer’s pages offer up some wonderful associative games for both the eyes and mind. Photobooth strips next to pages from 50s movie magazines; erotic pin-ups next to Antonioni film stills. However, this is no cabinet of curiosities, but rather, as Vince calls it, a “diary”, giving voice to a variety of histories, memories and desires. Here, he walks us through his world of images.

Do you remember the first time you fell in love with a piece of printed matter?

As a kid, I was always falling in love with pictures — most often photographs I came across in my father’s collection of US Camera Annuals: Irving Penn’s Summer Sleep (1949), George Rodger’s naked Nubian wrestlers, Richard Avedon’s society swans. The first thing that comes to mind, though, is not a photograph but a small reproduction I must have picked up in a museum shop, of a Paul Klee painting called Landscape With Yellow Birds (1923). It’s antic and charming, a very sophisticated cartoon. I push-pinned it to my bedroom wall when I was 10 and still have it here somewhere.

How long have you been living in your apartment?

I’ve been in this seven-room East Village apartment since 1976; before that, I lived in a much smaller walk-up exactly two blocks further east that I moved into right out of college. Not that much remains from childhood, except an embarrassing locked diary I kept when I was probably eight years old, but I do have some of the first vinyl 45s I ever bought: Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Bill Haley and the Comets, Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, The Drifters.

Where are you exactly, right now?

I’m seated at my computer, an old-school PC, which sits on what used to be Peter Hujar‘s dining room table; a sturdy antique painted deep blue that I inherited from him. As you might imagine, it’s stacked with printouts, press releases and publisher’s catalogues — a tonne of paper I’ll eventually throw away.

Is there one thing on the table you could never throw away?

It’s an item I couldn’t do without, probably one of the most valuable things I own when it comes to my collection. A small notebook with a grimy silver cover. I’ve used it to inventory my issues of American Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, one year to a page, from the 1930s to the 80s. When a year was complete, I drew a star at the top of the page, and I put stars next to what I considered important issues. Each entry includes the date, the cover artist and all the significant photographers and illustrators, with more stars next to the ones who did the best work. Tucked into the front of the notebook are separate checklists of British Vogues and Bazaars, Junior Bazaars, and notes on issues without covers and ones I need to replace or upgrade. All, needless to say, handwritten, and referred to at least once a day.

How do you “organise” your collection?

I’ve always tended to save printed images that caught my eye — gallery announcements, magazine covers, news clippings, tear sheets, flyers — often tacking them up on various open walls in arrangements that change constantly as new pictures come into my life. I keep them in antique and industrial filing cabinets and in boxes and baskets, some stashed under my bed. Things tend to pile up as they come in, mostly on a table in my living room, where I can share them with people who stop by. Little by little, they get filed away. But “organised” is probably not the word; I may not know where everything is, but I know it’s all here.

Tell me about the flat file…

The antique wooden flat file is one of the first storage pieces I bought when I moved into this apartment in 1976. There used to be a lot of inexpensive antique and used furniture stores in the neighbourhood and I was lucky to find this and a number of glass-front bookcases at those places that I could afford. The file cabinet is about five-feet tall and a little less than two-feet deep and really sturdy, with an embossed metal plaque that says “Hamilton Mfg Co, Two Rivers, Wis”. It has 12 drawers, six shallow and six deep, so it holds a lot of paper and supplies. The drawer Bruno and I photographed is one of the shallow ones, but it’s still quite capacious; nearly everything in the pictures was in that drawer when we started the project.

Is there any logic involved in ripping out a page?

Logic? Not really. Since I tend to collect whole magazines — thousands and thousands of them — I only tear pages out of issues I don’t need to keep in their entirety. Mostly, they’re ad pages, and I have another drawer and lots of boxes full of those. But, sometimes, they’re just images I want to remember and look at again. Often, they’re pictures that I’ve already tacked up on a wall in my kitchen that changes constantly, or pictures that eventually end up there. A lot of the pictures in that drawer are clipped from the sports pages of the Times or an issue of Sports Illustrated I found in the recycling bin. In general, it’s way more about desire and fetishism than logic. I want to keep these images in my life in some way.

What obsessions did you observe while rummaging through your stash?One obsession is obvious immediately: men and notions of masculinity have been at the core of much of my collecting, and there’s almost no spread in the book that doesn’t include a guy: Elvis, Brando, Drake, Alain Delon. Guys in basketball uniforms, in jockstraps and in the nude. But like I said, the drawer is capacious so there’s all kinds of beauty there, from all periods, in all styles and touching on other obsessions: Penn, Avedon, Beaton, Godard, Madonna, Warhol, Susan Sontag, Peter Hujar, movies, music, graphic design. This last is probably another overriding theme: there’s not a page, cover, ad or announcement in the drawer that doesn’t stand out as a piece of design.

Would you say paper is a democratic medium?

Totally. Some books and magazines are a lot more expensive than others, but price has nothing to do with aesthetic importance or power; real value is in the image itself. There’s trash and treasure at all levels of the market, and once something is printed on a piece of paper — especially if it’s a page in a magazine — it has to compete for attention alongside every picture ever made. It may not be an entirely level playing field, but if you’re really open to the wide world of images, it’s always a lively game.

I like how most of the pages are shorn from context…

Once something lands in the drawer, it’s usually minus any identity, captions or credits. That’s another part of the democratic process and it makes it easier for pictures to fraternise across genres and periods. There are plenty of pictures that image-savvy people will recognise but a lot more that are new, little-known or anonymous.

I guess that’s what makes it so personal.

The drawer is full of memories: pages I tore out of Harper’s Bazaar when I was still in college; gallery announcements I picked up when I settled in New York in the 60s; Vogue tear sheets Richard Avedon would otherwise have tossed out. Even if a piece of paper is not especially significant, it wouldn’t be in the drawer if it didn’t carry some weight and some history, however fleeting. But the drawer is not a museum, it’s a diary, a scrapbook, full of teen crushes and pin-ups I can still swoon over. The pleasure sparked by pictures rarely fades. It just gets more complex.

So, I suppose I have to ask… why does print matter?

As someone who lives surrounded by magazines — both vintage and brand new — there’s no way I can answer you with any degree of objectivity. Obviously, print matters as a historical record, as a very particular time capsule of the moment it appeared; whether it was 1945, 1984 or last week. And it continues to matter as the most pleasurable way to access pictures and print. In the same way that I think photographs need to be seen in person — as objects with qualities that can only be appreciated up close — I love magazines for their size, weight and the feel of their paper; for their style as well as their contents. Nearly all of this is lost online, and for many, I suppose, it’s good riddance. But what’s online is no longer a magazine and, since you’re asking me, I might as well be definitive: magazines matter.

The Drawer by Vince Aletti is published by Self Publish, Be Happy.

Credits

All images courtesy Vince Aletti