Nosrat Partovi only ever made one film: The Deer, in which she played a cabaret dancer who lives with a drug addict. It showed a fractured Iranian lower-class forced into poverty by the modernizations of the pro-Western Reza Shah in the 60s, and might have launched her career. But at a screening at Cinema Rex in August 1978, hundreds of people were burnt to death in a fire started by either Islamists, who saw cinema as a symbol of western immorality and decadence, or the Shah’s secret police, unhappy with the film’s content. The attack triggered the 1979 Iranian Revolution that overthrew the monarchy and led to Ayatollah Khomeini’s dictatorship. Partovi disappeared.

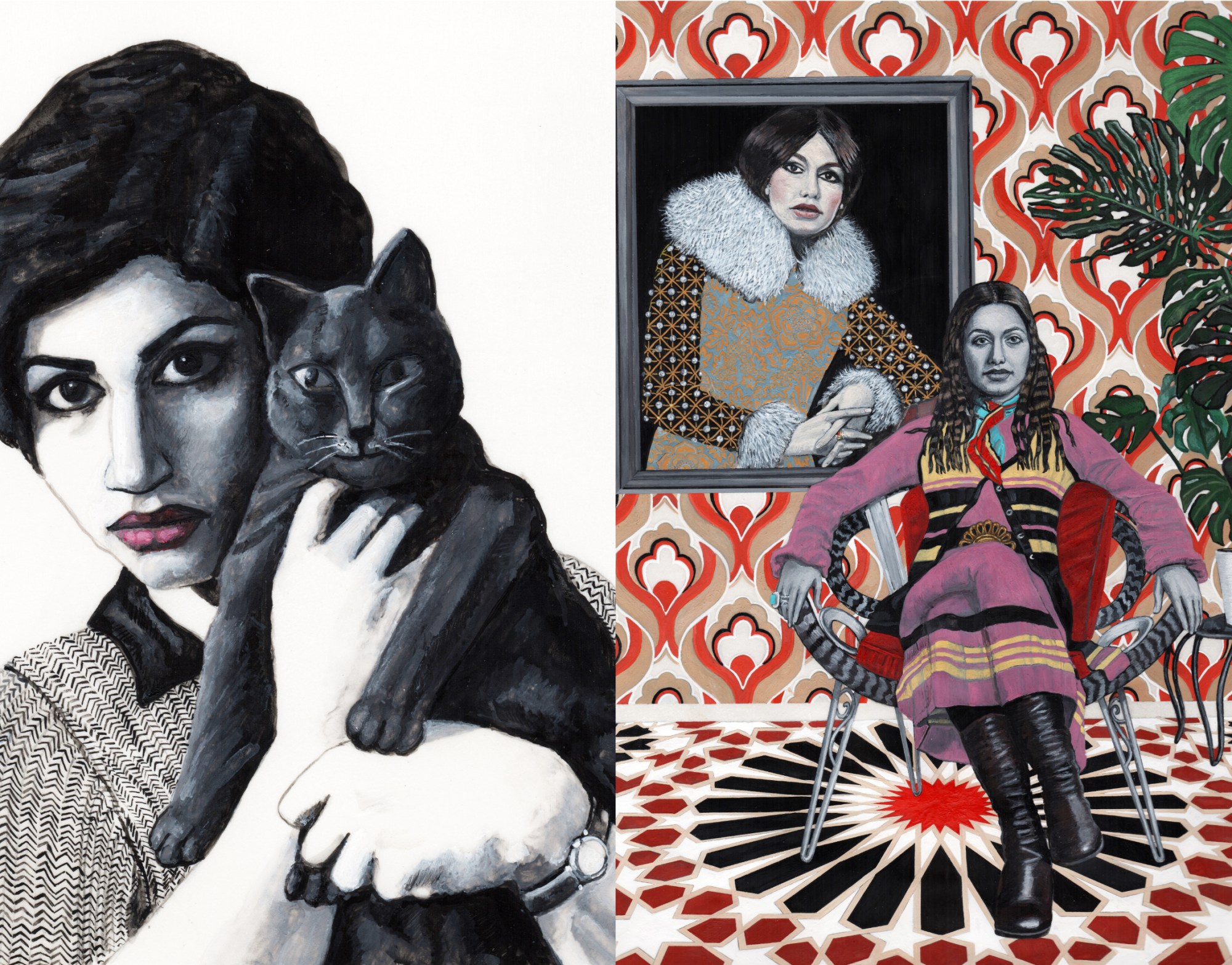

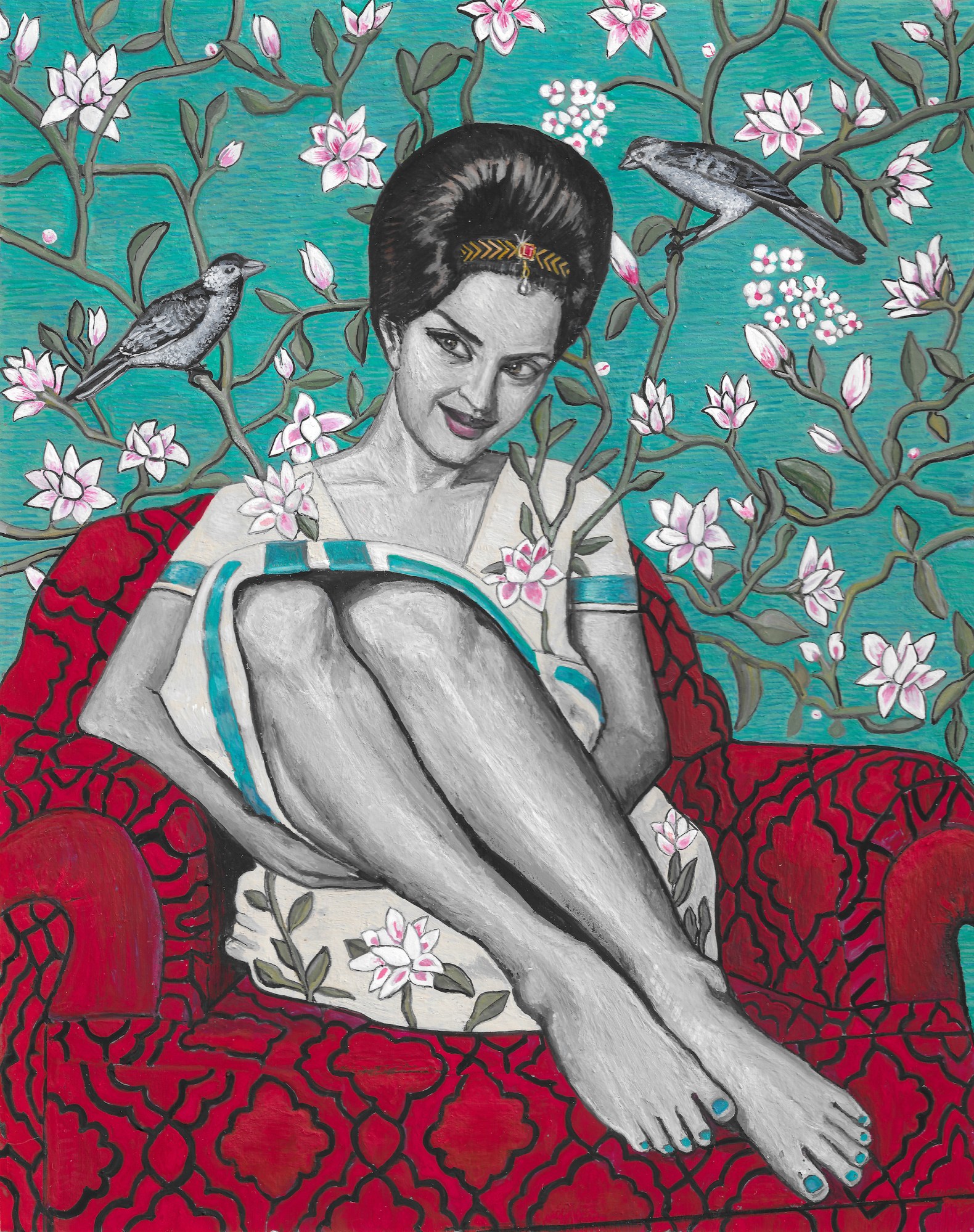

Today, the actor is immortalised in a painting of a polaroid held by the artist Soheila Sokhanvari in her exhibition Rebel Rebel. On pastel-blue walls, decorated in a geometric design that give the Barbican Curve a mosque-like feel, hang 27 Persian miniatures of Iran’s subversive female creatives — a style traditionally reserved for kings and the ruling parties. Dancers, actors, writers, poets, directors and singers confront their viewers — hair unveiled and clothes bold — just as they challenged the conservative culture that tried to silence them.

Many of their contributions remain censored under the Islamic regime, which last month killed Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old reportedly arrested and beaten by the morality police for having a little bit of hair emerging from her hijab. Since then, protests that erupted at her funeral on September 17 have entered their sixth week, despite a deadly state crackdown. In the streets, young women are burning their headscarves, cutting their hair, and lighting fires while chanting “death to the dictator” in the boldest challenge to the country’s leadership since the revolution.

“It’s always been women who have been the symbol of the Iranian government’s ideology, and their role has been told by men,” Soheila explains. In 1936, Reza Shah banned the female veil, allowing police to beat women for wearing one or rip off their headscarves and chadors off in the streets. The law was then reversed by the Islamic Republic under Khomeini and later Khamenei, who continues to enforce covering and restrict makeup, as well as brightly coloured, short or tight clothing. But “for the first time in the history of Iran, women are supported by their brothers and by their fathers and their husbands,” Soheila says, referring to the ongoing protests. It shows “the respect that they’re getting from the men. They will never, ever have to lose that. I think positive things have happened already.”

Today, Iranian women are among the most highly educated in the Middle East with a literacy rate of more than 80%, and they account for over 60% of the country’s university students. “That’s an incredible amount of young power that the government is actually ignoring,” Soheila says. Yet they need their husband’s permission to travel abroad and cannot run for president or become judges. After President Ebrahim Raisi came to power last year, dress codes have become stricter, and women are now restricted from certain banks, taking some forms of public transport, and government offices.

In Iranian society, “you see anyone who is seen and doesn’t behave demure as a whore,” Soheila says. She hopes to honour the creatives fighting against derogatory names like motreb and ragass that were used by conservatives to degrade them, suggesting they were selling their bodies for the eyes of the man. Most were ostracised for their craft, while actors Zinat Moadab and Shahla Riahi received death threats from members of their own families. It’s why she named the exhibit after the David Bowie song “Rebel Rebel”, about a boy who rebels against his parents by wearing makeup and tacky women’s clothes.

When Soheila received the commission for the show in 2019, she had no way of knowing her exhibit would feel as pressing as it does now. Her images: tiny, flat, black-and-white faces contrasted with psychedelic 70s backgrounds — wallpaper and clothes inspired by the rolls of fabric in her fashion designer father’s workshop in pre-revolutionary Shiraz, where women would come in looking for Western styles with a Persian twist — are exhibited to a haunting soundscape. Holograms of dancers speckle the show, and, at the end, a crystal ball plays film clips from pre-revolutionary Farsi films.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

The portraits in egg tempera on vellum depict Roohangiz Saminejad, Iran’s first female lead in a talkie, and the cabaret performer and singer Mahvash )so loved that, when conservative religious authorities refused to bury her in a Muslim cemetery after her tragic early death, there was an uproar and they relented) who oozes sexuality in a low-cut top. A fiery image of actor Kobra Saeedi, who protested the early demonstrations against the hijab in 1980, leans casually against a red and yellow zig-zagged background; while the poet Forugh Farrokhzad, who wrote of trying to “break the shackles binding women’s hands and feet,” clutches her cat.

Most left Iran after the revolution, which culminated in mandatory veiling and banned singing in public. But the country’s biggest popstar, Googoosh, returned to face arrest: “They tried hard to erase me — I mean, erase my name, erase my position, erase my songs, erase my face, erase the memory of me,” she told NPR. “But they couldn’t”. In fact, bootlegged copies of her albums remained popular and her fame continued for generations. Soheila’s painting of her is larger than the others, an explosion of colour, pattern and self-assurance.

“Iranian women are lionesses: tenacious and very headstrong women, who know what they want and get it,” Soheila says, both about the women in her show and those risking their lives on the streets today. “I come from a family where my mother ruled the roost,” and “my dad was a feminist.” Even her grandmother, who was illiterate, religious and wore a veil, was liberal and open-minded, fighting for her mother to go to university. Unlike the men imposing the rules, “she didn’t feel like she could ever force heaven onto anyone else,” the artist says. “She believed that women had the power to choose for themselves and still have autonomy of their bodies, which is very unusual for a woman who was born in 1910.” She adds, “although she wasn’t educated, she was enlightened.”

The situation in Iran, she adds, is not about religion at all. “I’m not against anyone who wants to kind of obey their own religion or wants to wear a veil. But I just don’t think that the country should tell these people what they should wear and what they should not do.” She thinks the West should put targeted sanctions on the Iranian leaders who have families abroad, as they should not be able to enjoy the freedom of the West if you bear a certain attitude towards women. “They have this double standard,” she explains.

Soheila is very aware that she could have faced the same restrictions had her family not had the means to flee to the UK in 1978. “When you think about how much freedom you have, to wear whatever you want — that’s a basic human right. If you don’t have that, I think it feels immensely oppressed,” she says. Beyond that, “I can be an artist; I can do whatever I want. I can sing and dance in the streets and nobody would ever arrest me or stop me. So, obviously, I’m very unhappy and concerned about my Iranian sisters, my Iranian mothers and Iranian friends. I think it’s important to be telling people [these stories] because it’s a very sad and poignant story to tell the world.”

Rebel Rebel is a celebration of fiery Iranian women who, despite the men’s best attempt to stamp out their light, burn brightly. “The amazing people,” Soheila says, “who are the grandmothers and mothers of the people who are in the streets today, punching their fists and fighting for their freedom.”