When the first issue of Self Service was published in 1993, eyebrows were razor sharp, T-shirts angsty, silhouettes were short and slinky, and the internet was still in its infancy. Designers introduced the world to their collections, not through catwalk livestreams, but in the ads that filled fashion magazines. Crafting visual dialogues with the people buying their clothes, campaigns pushed the boundaries of photography, art, music, film and fashion.

“There was a very different mindset and context,” says Ezra Petronio, who co-founded the magazine with Suzanne Koller in London. This was an era where, “you had to go to Rough Trade to buy a Daft Punk record, or you had to like go to a newsstand to get The Face or i-D.’’

“There was a different way of engaging with culture. It was a time when fashion was a little bit less of an industry, brands were just emerging. It was the end of the glamorous 80s. There was a strong energy,” he says. “Today, brands are in constant dialogue with drops, campaigns and imagery nonstop,” but back then they needed to synthesise their collections into a single campaign. “That’s maybe what made it a little bit more special.”

Now, in a new book of more than 300 fashion adverts from 28 years of the magazine, we can see the influence of the 90s play out again and again across those campaigns, in grunge revivals, acid house throwbacks, unencumbered celebrations of sexuality, and teen rebellion. Self Service 1994-2022, The Ads is a definitive reference guide to contemporary advertising, chronicling the sartorial shifts through the 2000s that have had a trickle up effect into the upper echelons of fashion today.

Throughout its history, Ezra Petronio and Suzanne Koller’s indie fashion title championed the artistic forces of the day: “the newcomers, the avant-garde and the established, the many free-spirited creatives, fashion radicals and creative minds, all those who have constantly explored and transgressed the norm through their undiluted imagination and ideology,” writes Ezra in the book’s introduction.

“It’s kind of a time capsule of strong image making,” he tells me over the phone, “when it was really about brands and designers trying to really work images that kind of resonated or echoed or mirrored what their values were, what that kind of projection of a woman or a man was.”

With the backing of fashion’s biggest names; among them Gucci, Dior, Prada, and Balenciaga, they were able to offer free promotion and advertising space to young and emerging designers; amongst them Raf Simons —Before he found cult status with his skinny-suits and rebellious menswear, Raf’s AW97 collection was featured in the magazine — Jean Colonna and more recently Supriya Lele.

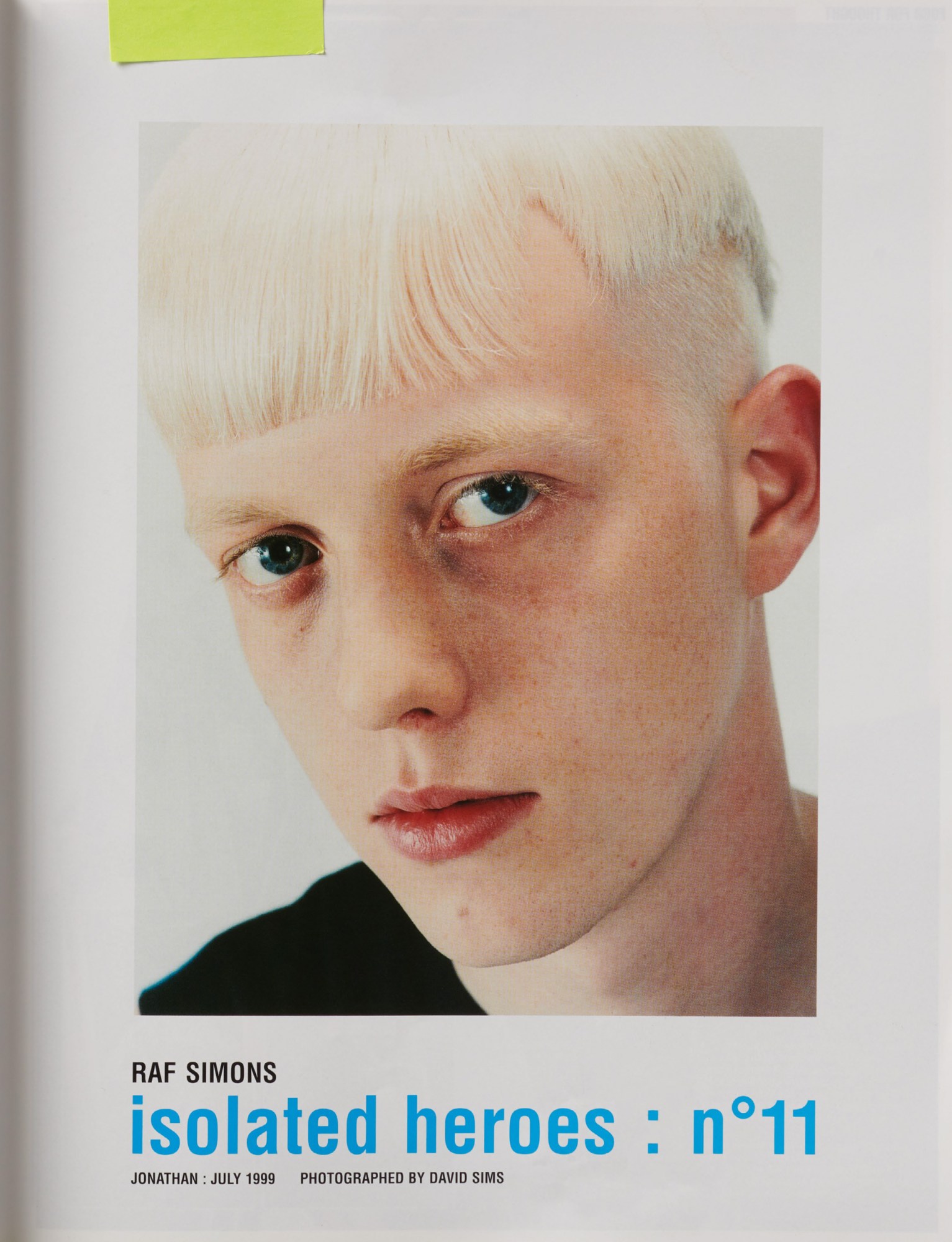

Driven by the youth culture of his hometown, Raf worked with the British photographer David Sims on ‘Isolated Heroes,’ two years later. He street cast non-professional models and took a series of portraits that showed little of the designer’s Spring/Summer 2000 collection. Instead, it had a timeless quality, challenging modern perceptions of masculinity and beauty, and became a highly regarded body of work. Bridging the gap between fashion, photography and art, it tapped into the notion that people buy what brands represent, rather than what they are actually selling.

Helmut Lang’s print campaigns relied on something similar. A double page ad features white sheets hung and knotted abstractly in a way that is reminiscent of the work of feminist artist Louise Bourgeois, who became something of a muse for the designer. Best known for her large-scale sculpture and installation art that used textiles to explore themes of domesticity, sexuality and the body, death and the unconscious. Helmut said he didn’t care whether she wore his clothing but made a little crown for her. “I never saw it as advertising. It was just another dimension of the work,” Helmut famously said himself. But his links to the art world afforded him a certain level of prestige that was rarely given to designers.

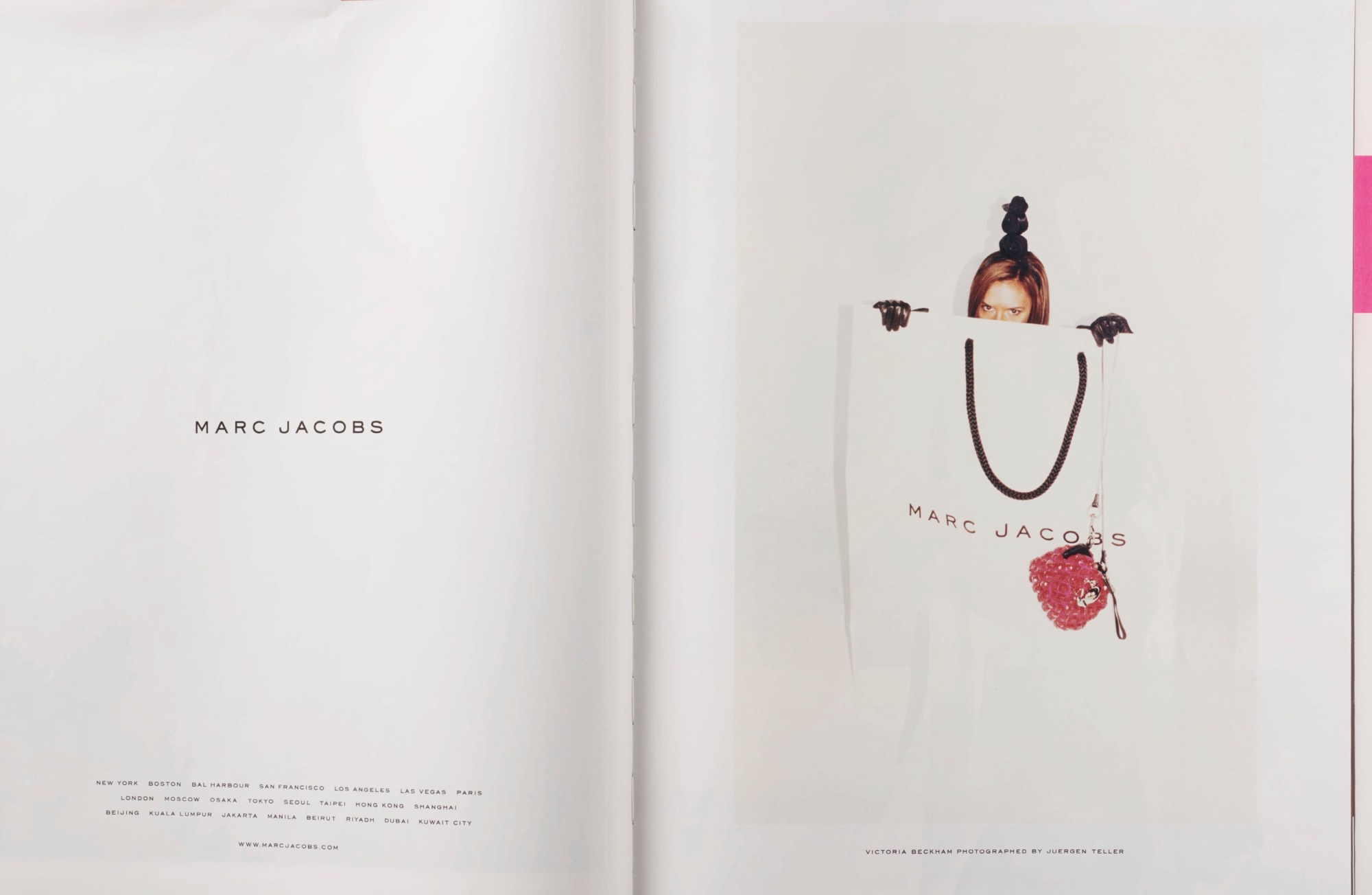

Others, like Juergen Teller, took a more playful approach to fashion. Juergen was the mastermind behind many of Marc Jacobs campaigns in the early 2000s, including one in which Victoria Beckham sprawls out of branded bags and pops out of boxes. It’s meant to be ironic, flipping the notion of stardom in a way that is more gritty than glamorous.When describing the shoot to her he recounts “‘You’re the most photographed woman in the world’, and fashion nowadays is all about product – bags and shoes – and you’re kind of a product yourself, aren’t you?’”

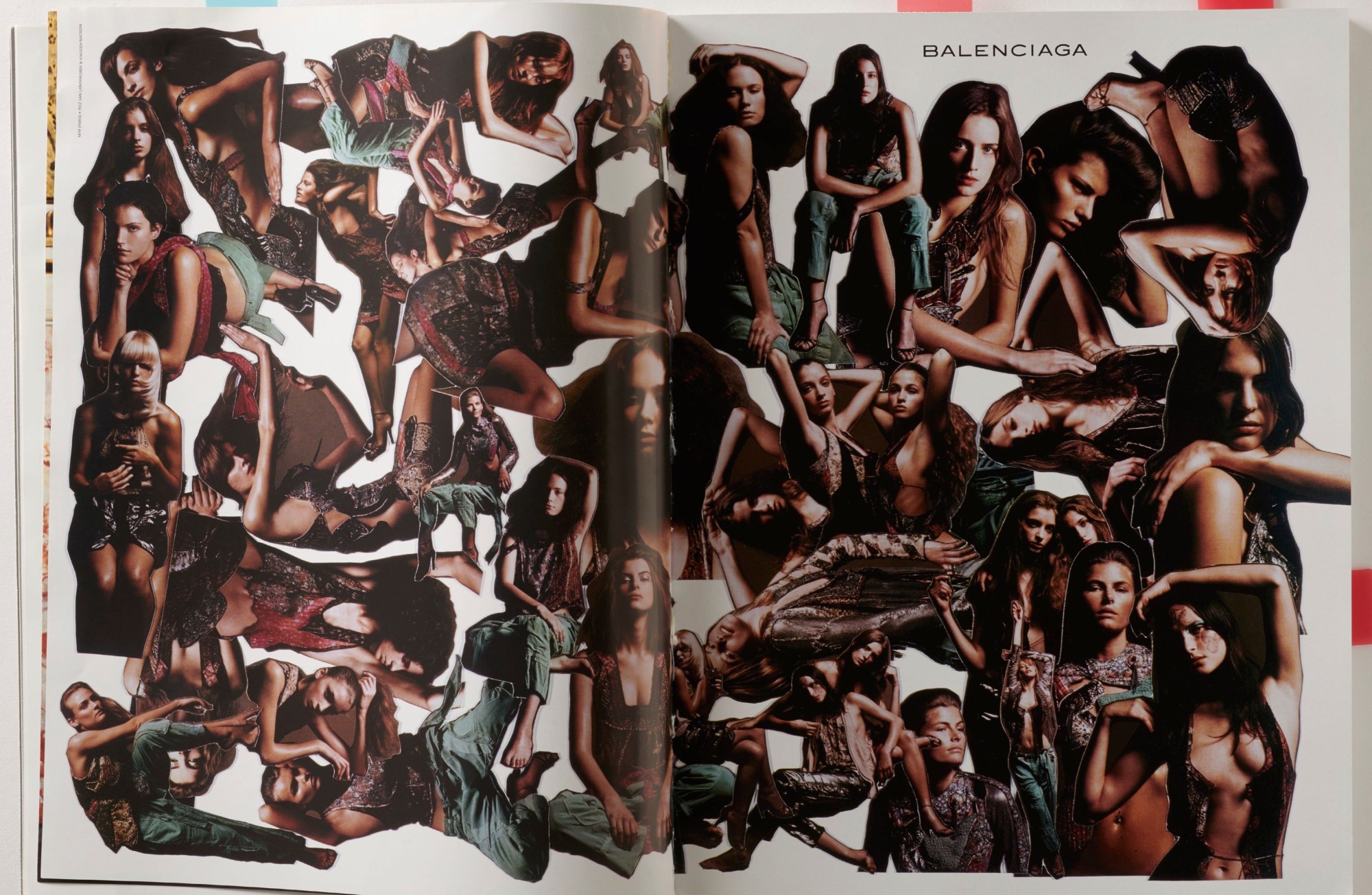

French graphic designers Mathias Augustyniak and Michaël Amzalag, best known as the creative duo M/M, meanwhile, collaborated with Yohji Yamamoto, Callaghan and Balenciaga on abstract, boundary-pushing campaigns. For the latter, they cut out images from a moody shoot by photographers Inez Van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin and rearranged it into a collage. For Callaghan, they overlaid a pointalistic sketch in white onto a gothic portrait.

It’s perhaps hard to imagine any of these campaigns existing today. But there’s also been a cultural shift. Gone are the heroin-chic days glamorising super-skinny models with pale skin, dark circles under their eyes and fried hair that made them look strung out. Neither are designers showing drunk girls sprawled out in a bathroom wearing their clothes, or prepubescent models wearing adult pieces.

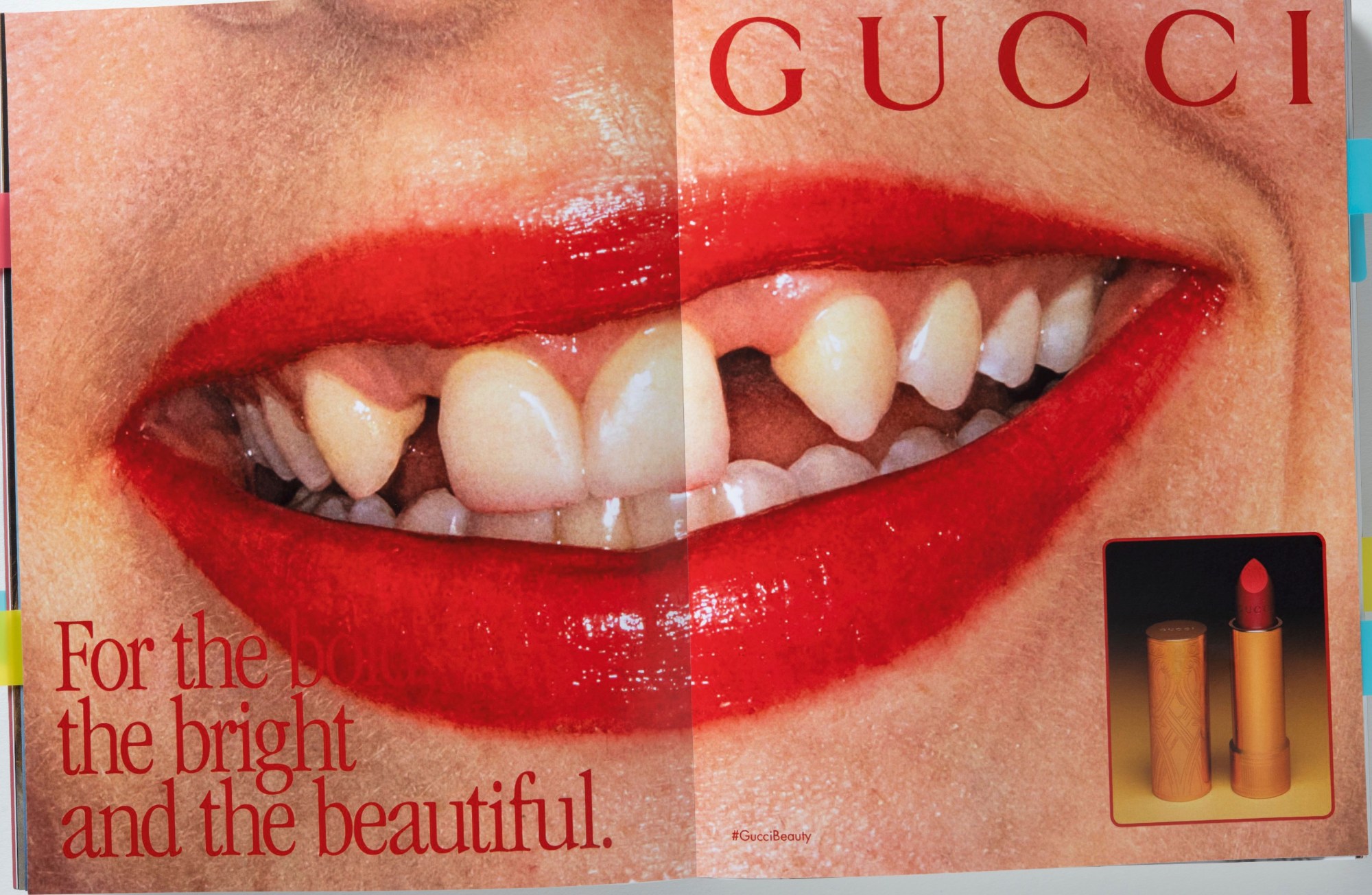

But that’s not to say image-making isn’t provocative in different ways. Alessandro Michele has taken a disruptive approach to inclusion that could benefit all customers. “Sometimes people think that fashion is just a good dress,” he tells Vogue. “But it’s not. It’s a bigger reflection of history and social change and very powerful things. If you want to produce something new, especially now, you need more languages. I don’t want to die in the marketing. In the end you need to sell, but it’s like a big fresco—and the fresco speaks to everybody.” Alessandro, in his work, bucks normative standards of beauty. For the launch of the brand’s new beauty line, in a campaign shot by the British documentary photographer Martin Parr, New York punk musician Dani Miller — the frontwoman for Surfbort – is celebrated for her gap-toothed smile. “Perfection doesn’t exist, so let’s celebrate the things that are wrong in a good way,” he adds.

“I think fashion is a great mirror into society,” says Ezra. “Things have changed so much and today obviously we are in a different era, it’s more complex, it’s more about diversity. But there’s less risk taking, I think, there’s a lot of freedom but there’s a lot of restraints. It’s so complicated and there’s a need to speak to new generations in a more modern… original way.”

Self Service 1994-2022, The Ads – New Edition is available now via IDEA.

Credits

All images courtesy Self Service