The exhibition Studio to Stage, up at Pace’s flagship space in New York, is a history lesson in music photography from the 1950s onwards. Across the gallery’s seven floors, you’ll find a riveting mix of images, sounds, genres and geographies – with the likes of Iggy Pop, The Rolling Stones, Miles Davis, Billie Holiday, Sade and the Spice Girls lensed by legendary image-makers such as Peter Hujar, Robert Frank, Irving Penn, Hiro, Ming Smith, Ari Marcopoulos and more. Exploring the myriad ways in which photographers have cultivated the mythologies of musical icons, the exhibition seeks to examine not only what it means to be a performer, but what it means to be a fan.

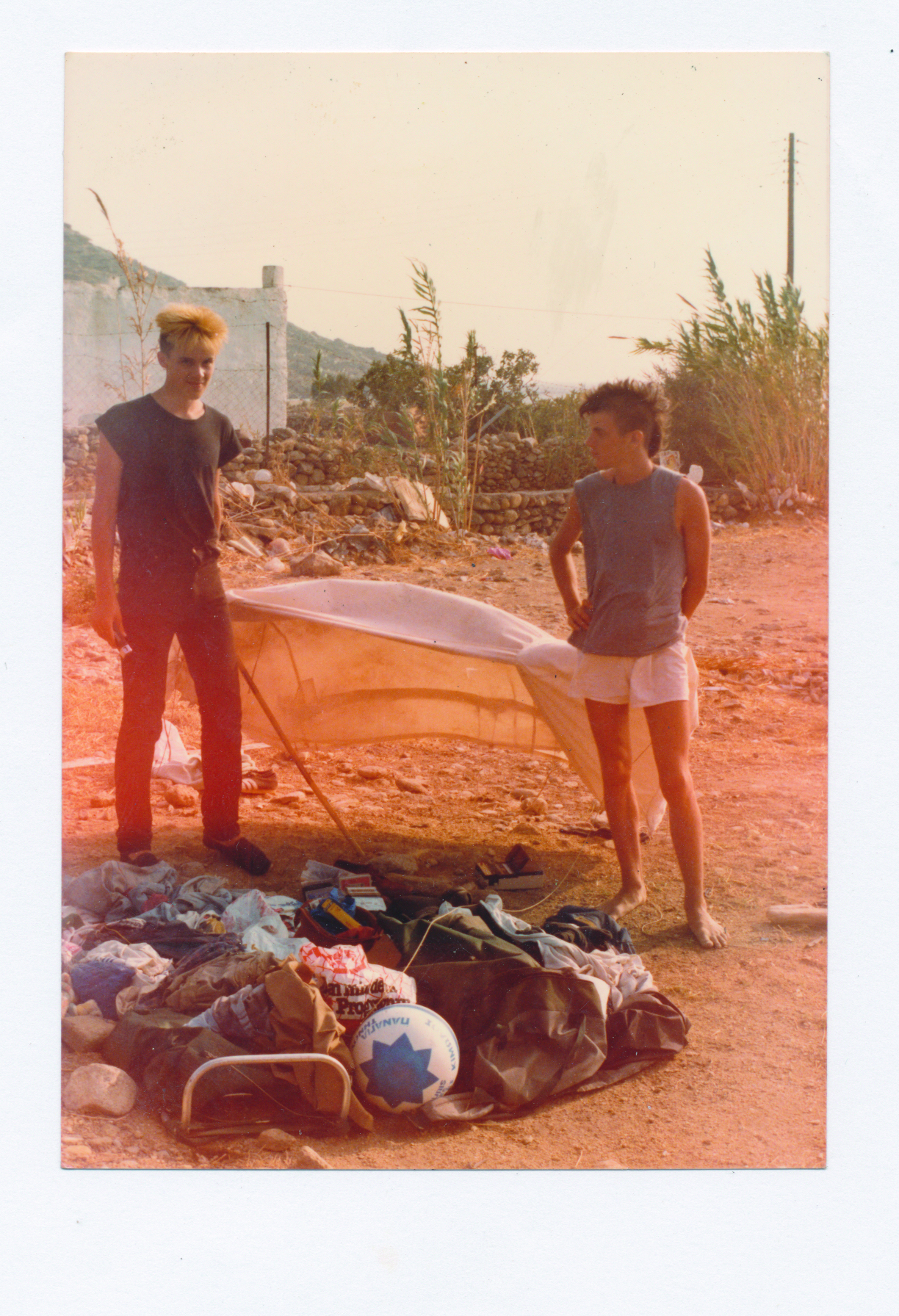

In the performance space on the top floor, Nick Waplington is exhibiting, for the first time ever, Made Glorious Summer. It’s a highly intimate work originally published in book form in 2014, taking its title from Shakespeare’s Richard III: “Now is the winter of our discontent / Made glorious summer by this sun of York / And all the clouds that lour’d upon our house / In the deep bosom of the ocean buried.” Against the backdrop of the “Winter of Discontent” of 1978–79 – a turbulent time of strikes that preceded the election of Margaret Thatcher as UK Prime Minister – the book traces Nick’s teenage years living in Surrey and West Sussex when British post-punk youth were politically active and protests would quickly turn into riots. Weaving personal snapshots, the countless records he was crazy over and the story of his deceased father, Made Glorious Summer is as much a portrait of Nick as a young man as it is a record of a time and place.

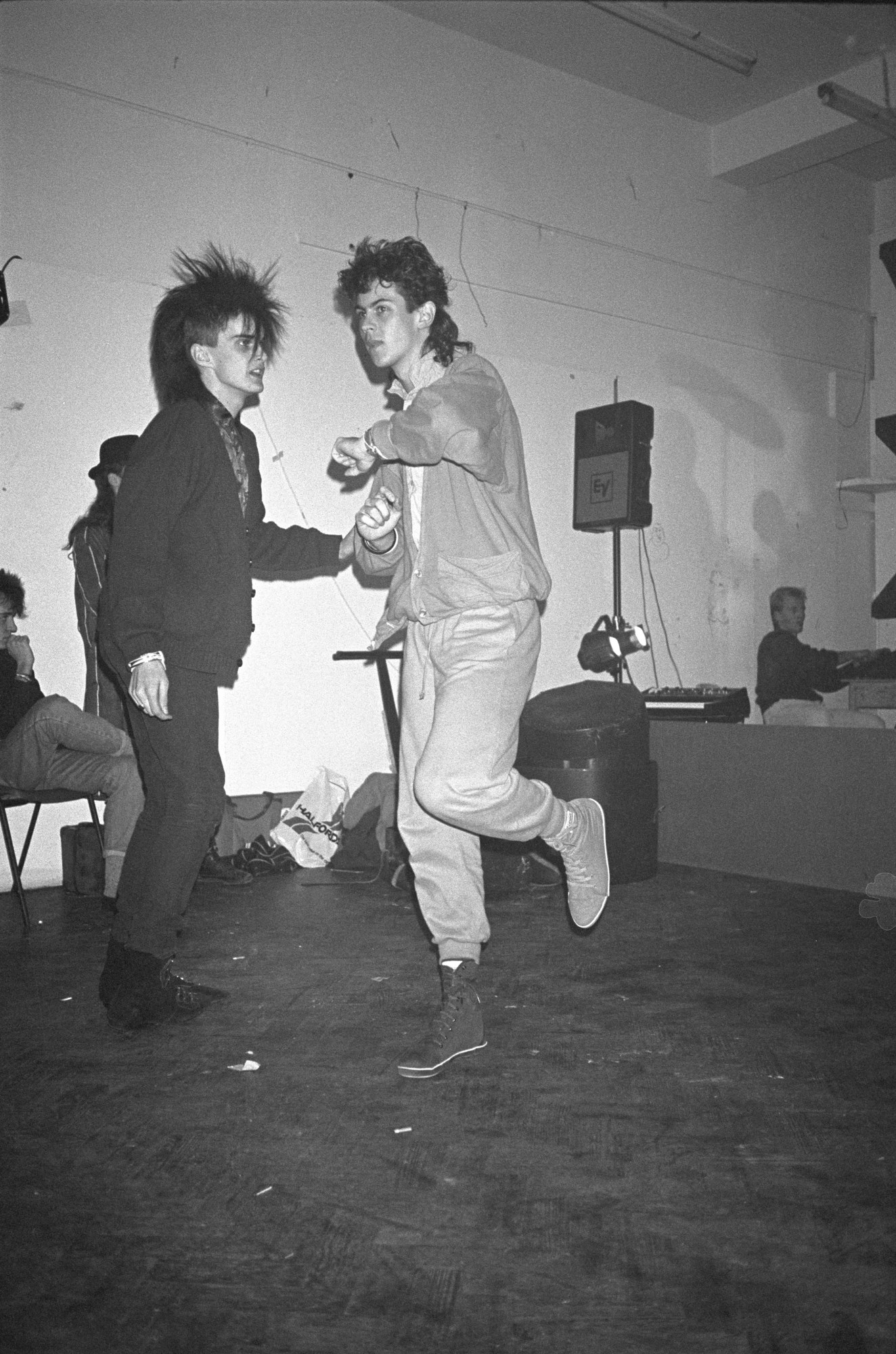

For the new Pace show, Nick has presented this work in conjunction with rare NYC clubbing shots taken in the late 80s early and early 90s — the heyday of house — to draw deeply felt connections between life and music. In this revelatory interview, Nick talks punk, protest and after-hours parties in the “Big Apple”.

What are your memories of the “Winter of Discontent”?

That winter was a wonderful time for me as a 13-year-old child. While I was acutely aware of the political turmoil, its manifestation in my life was only positive. The oil tanker drivers had gone on strike and my school, which was oil heated, had to close. We had a six-week extra holiday in the autumn term, but there was no attempt at home learning, and, of course, the internet was still 15 years away. So I spent most of my time skateboarding and going to see bands if they were playing at venues which allowed kids my age in.

This was when punk music was sweeping across the country… How did you get exposed to that world?

When punk started, I was 11 and liked Abba a lot. With no older siblings, I wasn’t exposed to music in the way some kids are and my parents didn’t have an interest in pop culture. When I got to secondary school in 1977, I was quickly introduced to punk by the older kids and found it super exciting. There were three distinct groups at school: the disco kids, the heavy metal-ers and the punks. Because punk was allied with skateboarding (which I was already into), I found myself in that camp. I didn’t have any of the clothes, but I liked all the pop punk that was in the charts like Buzzcocks or our local heroes in the Woking/Guildford area, The Jam and The Stranglers. Woking is 20 minutes from Waterloo on the train so I started going to the South Bank to skateboard, then off to record shops and concerts. I loved the Lyceum on the Strand because I could skate back over Waterloo Bridge afterwards and be home super quick.

You became involved with the record shops, right?

Yes. This was the beginning of independent music and labels like Rough Trade. I also began working with a few local fanzines (hand drawing the covers and doing the layouts), promoting gigs by local bands and, of course, playing in a band myself. The band was called Totally Devoid and, as my father said, we were “totally devoid” of any musical talent whatsoever. A few photographs still exist but luckily no music. The records in the book are the 7-inch singles from my collection, all of which I still have.

You have previously said that this period was about much more than having a “good time”…

Right. The music I obsessed on was tangled up in politics. By the time I was old enough for punk, anarchy was over, and punk’s rebellion had taken a left turn. The fact that punk was also involved with reggae helped me to understand more deeply what was going on in the UK. By 1980, when I was 15, I started going to Rock Against Racism concerts and Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament marches (the USA had deployed Trident nuclear missiles at bases in the UK, which had re-energised the anti-nuclear movement). It was a time of resistance and rebellion in squats, university campuses and teenage middle class bedrooms. There was also the apartheid in South Africa, and Thatcher had called Nelson Mandela a “terrorist”. South Africa House on Trafalgar Square stood as a monument to this oppression. There was a constant 24-hour protest outside, and I would go and lend support on a regular basis. Of course, I always had my camera in hand.

Made Glorious Summer also tells a parallel story of your father… Can you tell me about him?

My father grew up in Broxtowe, Nottingham on a large inter-war council estate where most residents worked in the coal mines. He went to grammar school and university and became a nuclear scientist. As nuclear was considered the safe energy form for the future, it meant people would no longer have to work down the coal pits. By the time the Three Mile Island accident happened in 1979 — and stopped most civilian nuclear programmes in the west — my father had been in the industry for a number of years and remained very pro-nuclear. Exposure to radiation probably caused the cancer which killed him at the age of 62 in 2009, but, of course, we can’t be sure…

What was your relationship like?

He was very violent towards me as a child and I thought this to be completely normal. I realise now that young children who suffer abuse always think it’s normal as they know nothing else. It becomes your reality. This is why the alternate reality I made for myself through music and art was all I lived for. I would say to myself: I will somehow survive this, it’s going to be better, I will make it better. I always had hope and I always had the music.

Eventually, we had it out, in my late twenties. It turned out that he wasn’t actually my father and he had an internalised rage which he took out on me. He apologised and life is about kindness and forgiveness, so we moved forward. I found myself in my bedroom with him, with my teenage things all around me as he lay there dying, helpless and without hope. The tables had turned and my mother and I were now in charge. We stayed with him, and he lived a lot longer than the doctors predicted.

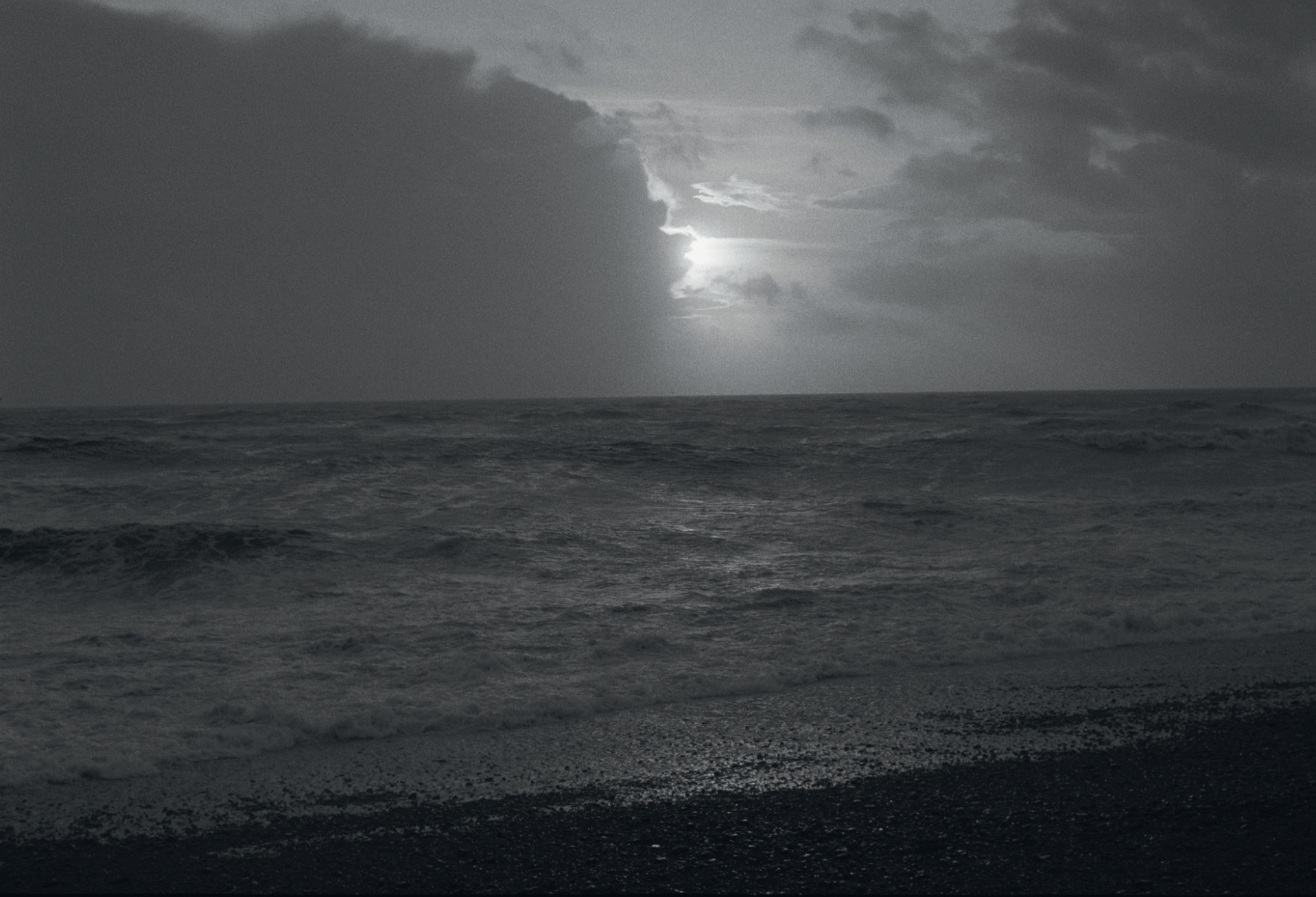

On a Sunday morning in September 2009, he had a massive brain haemorrhage and pints of blood came out of his mouth and my mother held him as he died. We felt relief that the suffering was over for him. Later that day, we drove down to Shoreham Harbour. It was a dark grey day of moody skies. We stood on the beach and looked out to sea. Suddenly, the clouds opened and little pools of sunlight danced on top of the waves. Now, whenever I go to the seaside on an overcast day, I look for those sunlight pools to appear and often they do.

The two seascapes that bookend Made Glorious Summer are super evocative…

The first picture shows the sun shining through the clouds on Brighton Beach the morning after the bombing of the Tory Party conference. The last picture shows the sun dancing on the waves over the solent, taken from the Isle of Wight ferry. That’s where my mother grew up, and I would spend my childhood holidays on the island, playing on the beach while my father sailed his dinghy in the sea.

How did the Pace show come about?

Matthew Higgs, the head of White Columns here in New York, introduced me to Mark Beasely at Pace and said we’d get on. Mark and Matthew are both originally from the UK and are both involved with music. Mark was putting together an exhibition about music photography from the 1950s onwards and asked me to participate. I’m showing Made Glorious Summer alongside images made in New York clubs – such as Sound Factory, Save The Robots, The Limelight and Jackie 60 – in the late 80s and early 90s, which is super exciting. As the work has never been shown before, it seems natural to show it here in New York. Plus, as far as I’m aware, not many pictures of these places exist, especially Sound Factory, which staged those legendary after-hours, Sunday morning parties. This was the heyday of house music, and the best music was found at gay clubs, so I gravitated towards them. It was very natural to take pictures.

Did you consider yourself an insider?

People have said that I make work about cultures that exist in the margins of society, but I don’t use the camera for access. The work always comes later. I’ve always just photographed “my life”, whether that’s on a council estate in Nottingham or in a club in New York. If I get really involved with the subjects, the work is made in collaboration with them. And this is why there often ends up being so many photographs. They become a record of a time passed.

What do you hope to achieve with the installation?

I don’t get the chance to exhibit very often, so I hope I have put together something that’s thoughtful and provoking. Ultimately, I want to make work that transcends the image. Or, put differently, I want to take the audience on my journey of how I got here.

‘Made Glorious Summer’ is on display at Studio to Stage, Pace, New York, until 19 August 2022.

Credits

All images courtesy of Nick Waplington