This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Ultra! Issue, no. 369, Fall 2022. Order your copy here.

It takes a truly special affair to lure Londoners from their barbecues on a warm Sunday evening, but Martine Rose is a truly special woman. And so, in June, for the designer’s return to the runway after a pandemic-enforced pause, her devoted crew turned up en masse – some slightly sunburnt – to a sticky-floored, latex-lined cavern situated in one of Vauxhall’s infamous railway arches. The space had been home to a branch of Chariots Spa, London’s legendary gay sauna, until lockdown had forced it to shutter its rainbow-decked doors. “It was the last Chariots to close down,” Martine sighs over a cup of tea and a cigarette outside her Holloway studio. “And it felt like that was a really important space for loads of my friends when we were growing up.”

In that spirit, the choice made perfect sense. Inclusion and community have always been at the heart of Martine’s world, and accordingly her shows have always invited her fashion family into intimate spaces across the capital (“I’d consider myself a true Londoner,” she laughs. “I grew up in South, lived in East, and now I’m North.”). Her last show, in 2019, took us inside her daughter’s primary school in Kentish Town, where we were seated alongside teachers on wooden benches; the year before, to a Chalk Farm cul- de-sac where local residents were sat next to the likes of Virgil Abloh and Luka Sabbat to witness her “love letter to London.” But this time, she was drawn to the mysterious allure of a space she’d never been allowed inside; to the sexual tension which proliferated there, and the home it offered men marginalised from the mainstream.

“I don’t want to sound like the equivalent of a white saviour, but Chariots and that whole area was home to this community on the periphery that I find really exciting, interesting, compelling and fun – one that deserves to be celebrated,” she says. Equally, while Martine had never been in the space during Chariots’ time there, she believes it once also played host to Strawberry Sundae: the underground rave where once she celebrated her 14th birthday party (its illicit nature evades concrete fact-checking). “I didn’t ever feel like I found my people at school, but I remember going to Strawberry Sundae and just being like, ‘This is it, this is where they are. This is what they’re doing,’” she recalls. “There I’d found this alternate universe; a space where you suspended reality and operated in this misty, smoky world, which broke down boundaries and blurred things just the right amount.”

By her own admission, Martine’s lifelong attraction to ‘outsiders’ was formed by literally growing up in those spaces: at nine years old, she’d go from church on a Sunday morning to Clapham Common in the afternoon, where she’d join her cousins and dance to illegal sound systems at their comedown parties; by her early teenage years, she had built a weekly calendar filled with Subterranea’; Club Colosseum; Twice as Nice. “Back then, every single night you had a range of club nights to go to, and, when you left, there was somewhere else to move on to,” she recalls. “London is a different place now. It’s far more gentrified, there’s just no space for that sort of nightlife to operate.”

The loss of clubs and thus decimation of nightlife across the capital has fractured its subcultural communities to the point of near-obliteration; the assorted weirdos who would once congregate together to share experiences on the same nights each week are now scattered across the city. “It was always a mashup: you’d have rudeboys, cyberpunks, all these different types of people,” remembers Martine of the crowds she’d find herself among as a teenager. “And there, for a period of time, there would be this suspension of reality where nothing else was relevant except the fact you were there with these people. I think that’s been lost slightly because people have access to things in a different way, and that’s changed the shape of things.”

The closure of Chariots offers a case in point, and it’s that climate within which her brand has found fervent fandom, in its lust for authentic interactions refracted through her resolutely modern gaze. While Martine has always maintained cult renown, in a post-pandemic world of disconnection, homogeneity and mass-market saturation, her focus on individuals and their idiosyncrasies resonates with particular potency. “She’s always represented the underground cultures she loves and it fully translates in the clothes and characters – it’s a whole world, and it’s always sexy,” reflects Lulu Kennedy, who first offered Martine Rose a platform via Fashion East back in 2009. “Martine is an anthropologist in her work. She uses fashion to investigate humans, their desires and their ways of presenting themselves to the world,” continues Charlie Porter. “She is saying something about how humans are, and how humans can be.”

“I just love people; they interest me,” Martine smiles. “I never felt like I shared a point of view with conventional people, so I’ve always been interested in the people in the shadows, on the periphery.”

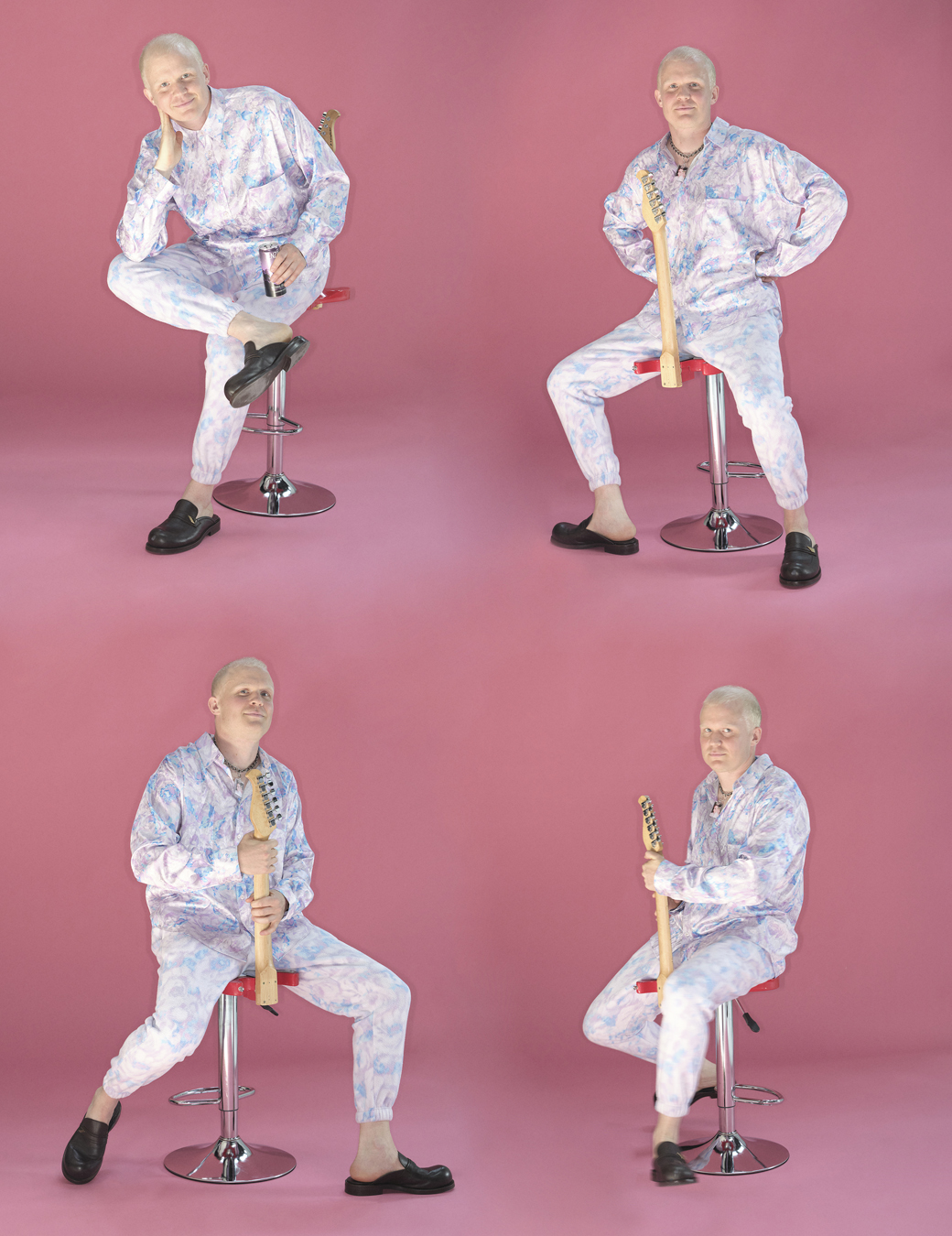

Martine describes herself as attracted not to weirdness but to “wonkiness” – to things that sit a little off – and it’s precisely that which makes the clothing that she designs so uniquely attractive: the fact that not only is it created in tribute to “wonky” people, but that its very design is off-centre. While working for Demna at Balenciaga, she masterminded the oversized Balenciaga silhouette that has come to define much of menswear’s overarching aesthetic, this season she started her collection by draping pieces on the body and finding attraction in the tension that materialised through shrunken sizing and constricting plays on proportion. It was the result, she thinks, of the pressure that she and her team had been under through the pandemic’s profound effect on their business and livelihoods: “I generally don’t set out with an intention, but it quickly became about pressure and release,” she explains.

“I never felt like I shared a point of view with conventional people. I’ve always been interested in those in the shadows and on the periphery.”Martine Rose

That sentiment soon translated into sexual tension: into pieces pulled taut or askew around the body to suggest “the accidents involved in urgent sexual encounters or hurried dressing afterwards”, into zips half-fastened at the back, or left bulging and exposed at the crotch. As things developed, too-tight leathers and cropped, clubby tees began to allude to the eroticism of Chariots’ archetypes. But, there was also something magnetically mundane about the surreptitious subversions of office-wear she designed. They evoked “an illicit snog behind the photocopier” – think of Matt Hancock’s lockdown love affair and you’ll get the gist. “If you actually break the collection apart, it doesn’t make that much sense,” Martine grins. “It’s how you put it together that really tells the story.”

There were Gay Xchange slogans, but also “random shit, like puppets”; belts which could convert into BDSM restraints alongside polyester shirting; keyrings suspending sexed-up photos by Roxy Lee hanging from wilfully ordinary workwear. There was hair and make-up that evoked Derek Ridgers photographs of eighties punks sweatily snogging in Northern nightclubs; a new Nike trainer she’d designed, a pair of Shox, which blended their shotter-at-the- end-of-the-road familiarity with a hyper-elevated heel. “The collection is really an amalgamation of loads and loads of ideas pulled together – but they don’t often fall in line,” she says. “I’ve always said I’ve wanted to design the breadth of a wardrobe: I always want the show to feel like a bit of a pick n mix.”

That in itself is a wonky approach: while Martine’s shows might read as character studies – in part due to their exceptional casting, which comprises everyone from postmen to local bar girls who she and the team “fall in love with” each season – the clothing itself is often perversely tweaked normcore (after all, it was Martine who essentially started that movement). She describes her interests as lying in “the tension between fashion and ordinary realities,” but that phrase could just as easily be applied to the world she inhabits.

As a designer, Martine sits within a curious space: she is loved by the fashion industry, by superstars like Drake (who made a cameo in one of her pandemic presentations), and by behemoths like Nike. But she is resolutely low-key: she is less engaged with the structures of the industry than almost any other designer who inhabits it, showing as and when and how she pleases (back in 2015 and strapped for cash, she simply showed a single look). In fact, you’re far more likely to bump into her with her kids on Holloway Road than you are at a fashion week dinner party. “She’s the exact same now as when I first met her fifteen years ago,” Lulu shrugs.

“It’s not like I’ve plotted out a path to not partake in anything; it’s not an intentional thing. Maybe it’s insecurity,” Martine reflects. “But it wasn’t so long ago that going to Paris was really intimidating. Nobody looked like me; there wasn’t anyone in fashion who felt like me. I don’t speak French. I needed to find another way. I never wanted to feel like I was in a fashion sausage factory.”

That being said, with her brand making its return to the runway, Louis Vuitton’s CEO Michael Burke sitting front row in the old Chariots sauna, and with an injection of investment and infrastructure from Tomorrow Ltd and a calendar of Nike launches in the pipeline for 2023, Martine is finding herself more visibly centralised than she’s ever been. So what next? “I’ve never been a planner; I’m a bit scared of planning,” she grins. “I always like to fly by the seat of my pants. I want to explore womenswear more; I want to find out who that woman is I’m making clothes for. I want to grow things, but in a way that feels exciting. But most of all, I just want to find ways of telling stories and bringing people in. That’s the plan.”

If anything proved she’s on the right path, it was the afters in Vauxhall. Across the road from the venue: a local drag act and pints at legendary gay pub The Royal Vauxhall Tavern, followed by a night out for whoever was still standing at Horse Meat Disco. “I don’t want to create something that feels removed or distant,” she said backstage after the show, where she held her daughter on her hip while the models chanted her name. “Whatever I’m experiencing, I aim to take everyone with me.” “Usually I get a migraine by the end, so I do a bit of chat backstage and then do a backdoor boogie out,” she grins now, in hindsight. “This time, I was like no – let’s go out! I want to blow off steam and dance the night away.”

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more from the new issue.

Credits

Photography Johnny Dufort

Fashion director Carlos Nazario

Hair Jawara at Art Partner using Dyson and Fekkai

Make-up Mel Arter at Julian Watson Agency using Fenty Beauty

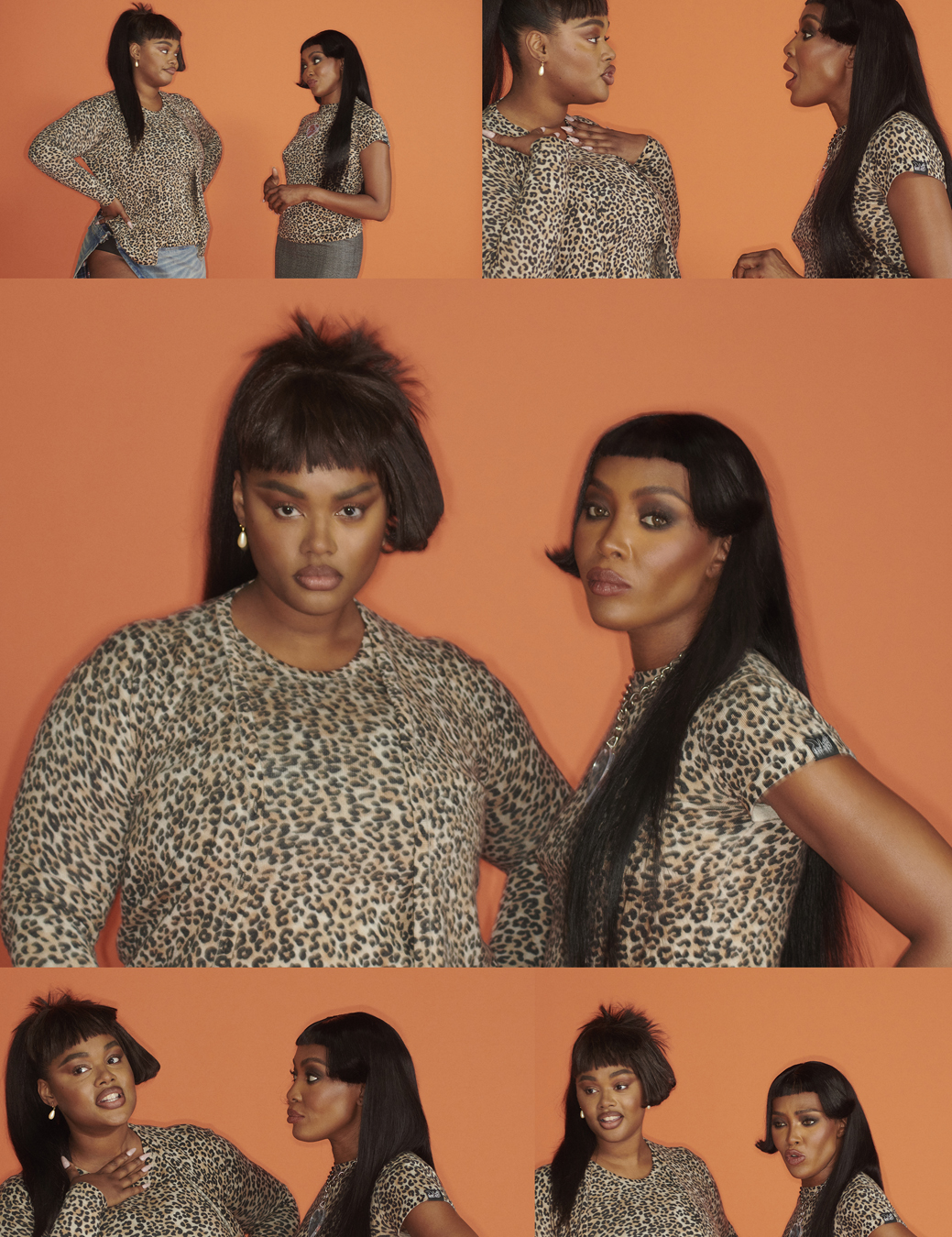

Make-up (Naomi Campbell) Ernesto Casillas for Pat McGrath Labs

Tailor Michelle Warner

Nail technician Michelle Class at LMC Worldwide using Sally Hansen

Set design Polly Philp at The Magnet Agency

Photography assistance Alberto Gualtieri, Pedro Faria and Daiki Tajima

Digital operator Anna Olszewska

Fashion assistance Raymond Gee, Melina Frangos and Emily Jones

Hair assistance Selasie Ackuaku, Alessandro Spiota and Hiro Furukawa

Make-up assistance Mari Kuno

Make- up assistance (Ernesto Casillas) Lee Burnett

Set design assistance Chloée Maugile and Cecilia Dumont

Production DoBeDo Represents in collaboration with Bellhouse & Markes

Casting director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING Streetcasting Alejandra Perez

Models Naomi Campbell at Women, Goldie, Precious Lee at IMG, Jana Julius at Storm, Humi at Models1, Billy Trick at Head-Office, Jack Day

All clothing, shoes and accessories MARTINE ROSE