It’s rare for an artist to achieve greatness in one discipline, let alone several. That’s what made William Klein a creative freak of sorts; his countless innovations across painting, photography, film and graphic design saw him revolutionise a number of fields — each with bold irreverence.

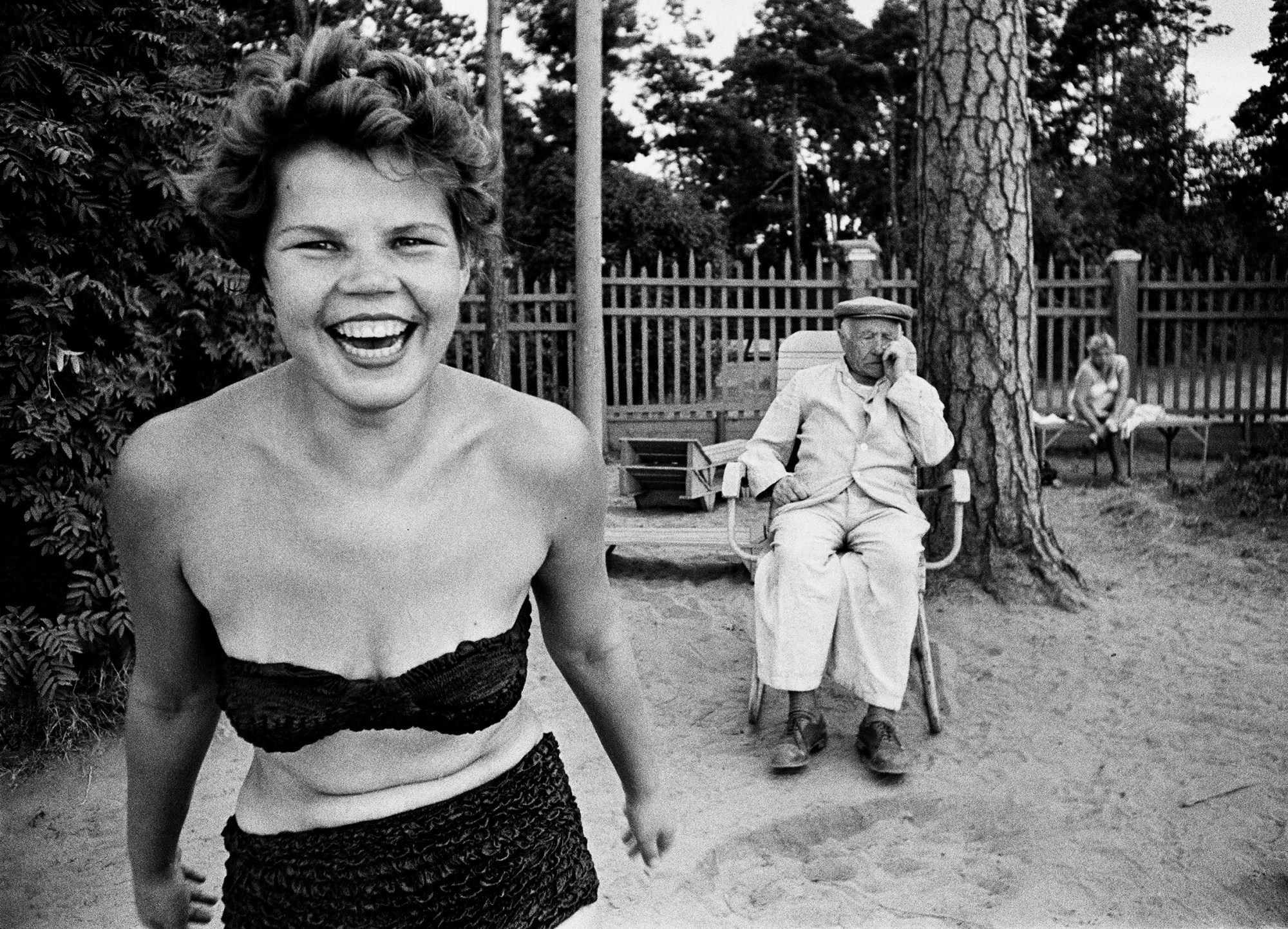

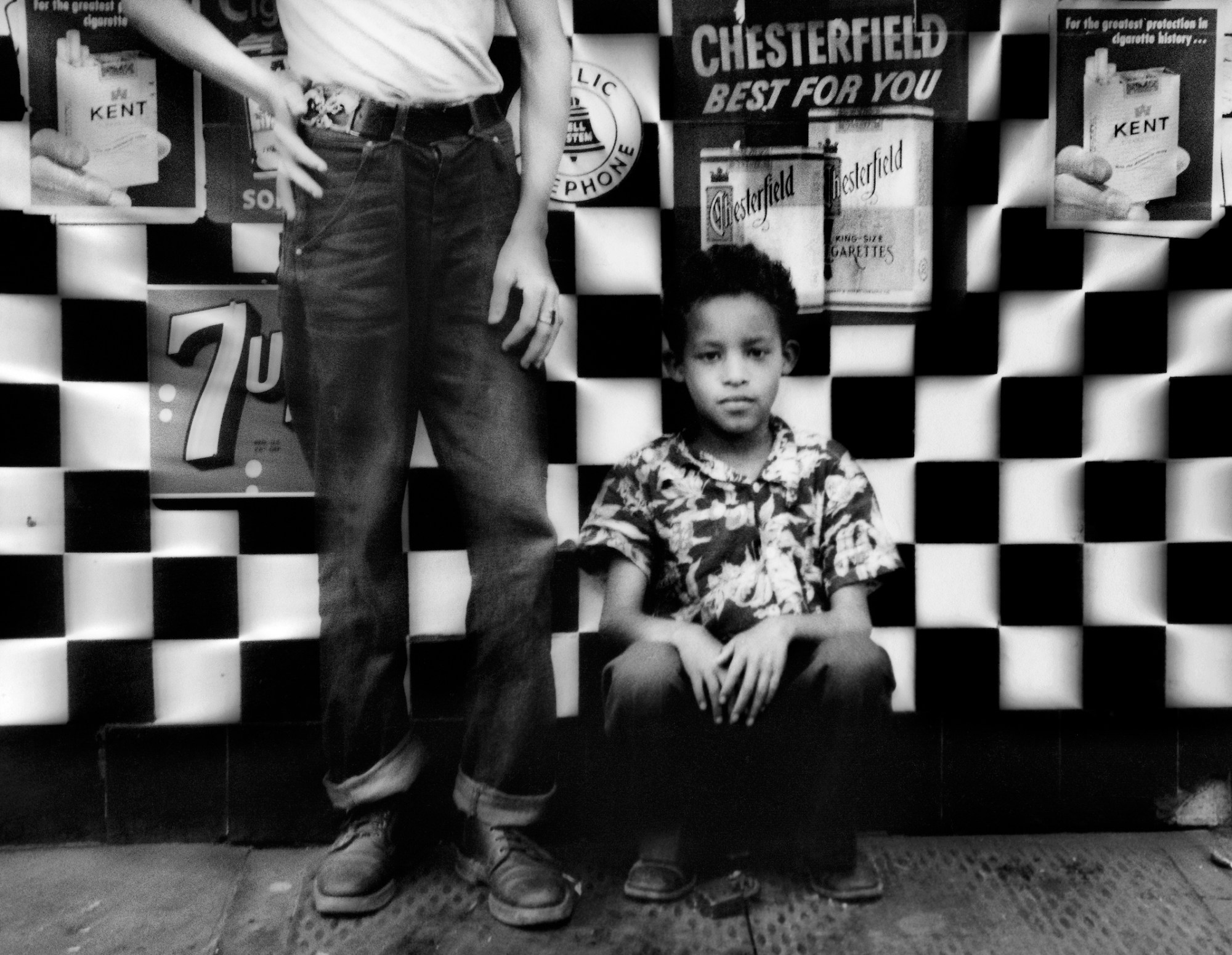

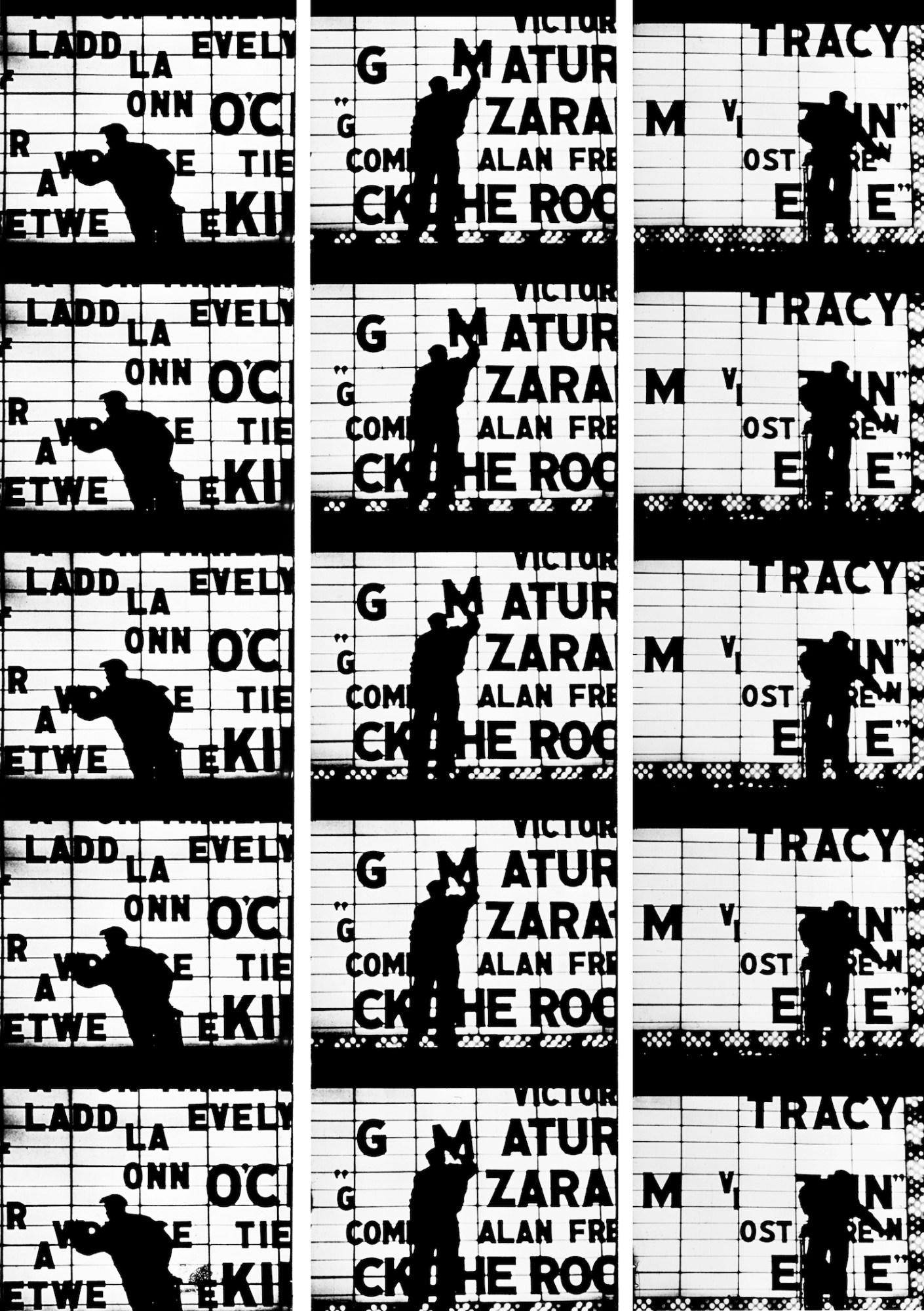

Packing in nearly seven decades of work, YES: Photographs, Paintings, Films, 1948–2013 — the title of Klein’s survey at New York’s International Center of Photography — is a kind of “homecoming” for the artist, who passed away earlier this week aged 96. It was in the Big Apple that Klein — on the back of a short spell in Paris dabbling in painting under the tutelage of Fernand Léger – made his magnum opus, Life is Good and Good for you in New York: Trance Witness Revels (1956). Using fast film, high contrast, grain blur, a wide angle lens and heretical framing, Klein compounded accident and abstraction to invent his own icon of the city. “The kinetic quality of New York, the kids, dirt, madness — I tried to find a photographic style that would come close to it,” said Klein. “I could imagine my pictures lying in the gutter like the New York Daily News.”

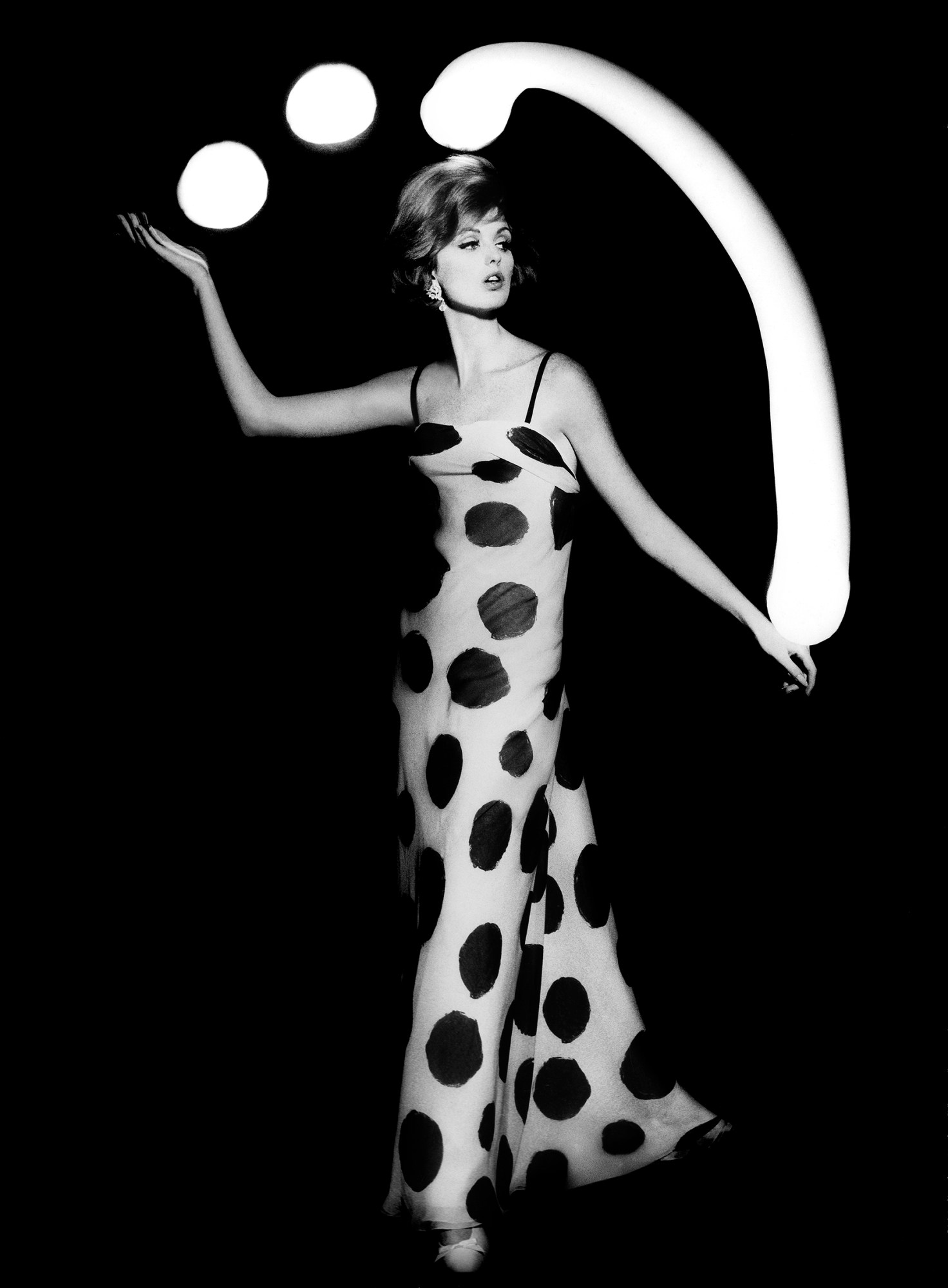

Books on Rome, Moscow and Tokyo followed, each with a different approach, and each pushing the limit of what photography could do and be. If Klein’s nature was Dada, his fascination with typography, urban junk and the absurd presaged pop art. Alongside his street-level assaults in the 50s and 60s, Klein was juggling commercial work for Vogue. At the behest of the extravagant art director Alexander Liberman, Klein injected the “grit of life” into the magazine’s glossy pages. Models were taken into the streets and captured in compositions that exude an edgy, intrusive aesthetic. Klein’s subversive stance towards the rules of “good taste” jolted the elitist realm of fashion photography, yet greatly influenced his peers.

Klein left Vogue in 1966, but the fashion world would be the subject of his blistering satire, Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? (1966). His films are as ground-breaking as his photography: Broadway By Light (1958) is possibly the first ever pop art film, while his offbeat documentaries on Muhammad Ali, May 68, Black Panthers, Little Richard and Handel’s Messiah (1741) beguile for their spontaneous cuts and category-defying flair. Perhaps more so than any, Klein’s oeuvre reminds us that art — in whatever medium — is not so much a product but a vision.

Here, ICP’s Curator at Large David Campany walks us through a lifetime defined by restless, genre-bouncing creativity.

How did Klein find himself in Paris in 1948?

Klein was born to a Jewish family on the edge of Harlem in 1928. As a kid, he fell in love with modern art, roaming the New York museums. After the war, he was in Germany with the US army for two years but was desperate to get to Paris. There was a chance to study art, and Fernand Léger was taking students. Klein was a painter, first figurative then abstract. But Léger’s advice was to think beyond the gallery, maybe toward architecture or new media. Klein’s paintings led to a commission to build a room divider made of rotating panels with graphic designs, for an apartment. While photographing it, he spun the panels and loved the blurring in the long exposures. It sent him into the darkroom to make hundreds of purely abstract photographic works, just with light on paper. They are full of exuberant play and invention. In Paris, these were seen by Alexander Liberman, art director of Vogue, who, in 1954, asked Klein to join the magazine back in New York. From there, he went in two directions at once, becoming both one of the great fashion photographers and one of the most original and ground-breaking street photographers.

Klein photographed stretch stockings for his first Vogue story… How did he begin experimenting with the models, taking them out into the streets and bringing the streets into the studio?

A big part of photography is creative problem-solving and Klein could make striking images out of unpromising subject matter. You can see it in his early fashion still lifes. The reigning fashion photographers of the 50s were Irving Penn and Richard Avedon but Klein had an impatient energy. Almost as soon as he was working with models, he was breaking the rules, going out into the streets and improvising with them, inventing poses that were ironic and almost mocking of high glamour. By the early 60s, his irreverent attitude was everywhere in fashion. I think you can tell that his inventiveness came out of restlessness. He was easily bored and had a deep suspicion of any establishment values.

Dorothy McGowan, one of the models Klein worked with, was a Brooklyn street kid, right?

Yes, McGowan and Klein were terrific collaborators. She was working class, and plucked to become “the face of fashion”. So, like him, she didn’t take that world too seriously. There’s a great Vogue feature from 1962 where she’s surrounded by abstract light patterns. The images were long exposures. In the dark, an assistant dressed in black stood behind her moving lights around. Then a flash illuminated her clothes and face. Three years later, when Klein was at the height of his powers as a fashion photographer, he made his first feature film, Who Are You, Polly Maggoo?, and McGowan stars as Maggoo in a story close to her own. It’s a pretty acerbic satire on the fashion world — stylish, funny, charismatic and beautiful to look at, because that world really is like that… But Klein pushes at it, pokes holes in it, drawing out some very human contradictions and frailties. Fashion is very hard to get right in cinema, but Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? comes close.

Let’s rewind a bit. In 1954, while working for Vogue, Klein was also letting loose on New York, taking in-your-face shots in the rough and tumble streets. Yet Vogue deemed them too vulgar…

Fashion paid the bills and Klein had time to do other things, especially his street photography which was equally rule-breaking: grain, blur, cajoling his subjects, inviting them to react and respond up close to the wide-angle lens of his camera. He saw clearly how New York was grim and money obsessed but it had (still has) a self-deluding reputation for equality and success that he just had to prick. He was also upfront about the ingrained racism of the city, but his photographs really celebrate Black life. There’s no dwelling in victimhood in the way a lot of well-intentioned social documentary photographers did in the 50s. With hundreds of photographs, Klein designed his own book, doing the editing, layout, captions and cover. It’s a total work of photographic art. American publishers wouldn’t touch it. But it would appear in Paris, Milan and London, and its impact was global. For a lot of photographers, it changed everything.

What, in your opinion, makes the book so successful?

Its sheer energy is breathtaking. There is not one dull photograph and not one dull layout. It twists and astonishes with every turn of the page. A little bit Dada, a little bit pop art, a little bit paparazzi, sarcastic one minute, deeply affectionate the next. The book has an irrepressible feeling that anything is possible and that photography, like life itself, is unpredictable. It’s not easy to discern exactly what Klein’s opinion or point of view is. The book is such a kaleidoscope.

Klein coupled his shots with some brilliant, Beat-inspired captions. Does one stand out?

“Advertising is mainly grotesque. Such a conspiracy has developed between advertiser and public that it has become a gag — the public is grateful, yaks, and goes along.” That’s from 1956 but it feels like 2022.

Tell me about the books that followed…

After New York came a book about Rome, which I discovered on the shelves of a thrift store as a student. It’s like a Fellini movie in book form. In fact, it was Fellini who invited Klein to Rome, to photograph prostitutes as research for his next movie. When filming was delayed, he photographed all over the city. The book on Rome has a bitter glamour, set amongst the ruins of the city, combined with a contemporary street-level modernity. Then came Moscow and Tokyo. Klein would slip away from the officials looking after him, venturing out to meet people alone. Those four books are amongst the very greatest achievements in photography and publishing. Often imitated but never equalled, they are an endless fountain of visual invention, with a genuine love of life and people that is as infectious today as it was all those decades ago. This is real humanist photography, not in that patronising or sentimental mode but in the true sense, engaging with the full complexity of people and their circumstances.

Do you have a favourite city book?

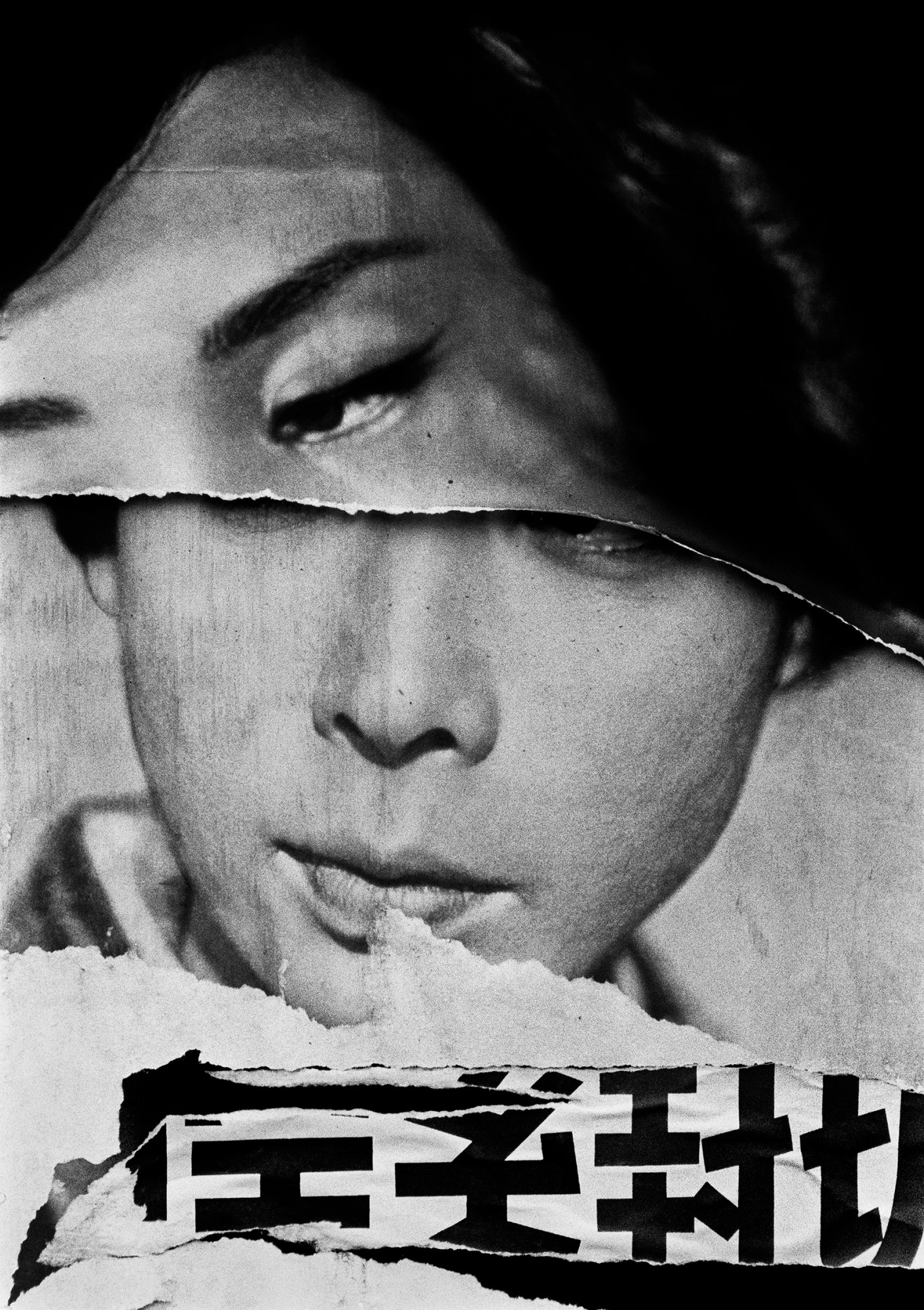

I think Tokyo (1964) is remarkable. Klein was upfront about being in a culture that, at first, he just didn’t understand. Somehow, he managed to connect with so many people — artists, performers, politicians, labourers — and out of this came photographs of real joy and wonder. Klein has always rejected the idea of objectivity, but not authenticity. What’s authentic is the encounter and the image is the result of that encounter. There’s a sense of interaction and theatre, of improvisation in the moment. It’s a kind of dance between Klein, his camera and those he meets.

Those photographs of Tatsumi Hijikata, Kazuo Ohno and Yoshito Ohno — shot on the streets of Tokyo in a single day (27 June 1961) — are a really wonderful record of the early Butoh movement. In what ways was Klein interested in performance?

Klein understood performance simply as part of being human. We all perform, presenting ourselves to strangers, to friends, to cameras. Of course, most often, it’s a matter of conformity, of fitting in with society. But Klein was attracted to anyone breaking with all that. Street kids, outcasts, provocateurs. The avant garde Butoh group was really pushing the boundaries of what was socially acceptable in Japan, twisting gender roles, overturning dance conventions. Klein took them out of their rehearsal studio and through the winding streets of the city, encouraging them to play to the gathered crowds. The year Tokyo was published, 1964, Klein made a film about the young Cassius Clay (who later changed his name to Muhammad Ali). Another uncontainable non-conformist, Clay was regarded as a pariah, an outspoken critic of white American society, but he so witty and quick with it. Klein saw he was a natural performer who knew exactly how the camera could capture and present him.

After a long hiatus from the fashion industry, Klein returned with Fashion in France (1986), highlighting the work of emerging all-stars like Karl Lagerfeld and Jean-Paul Gaultier. What had changed in that time?

In the years he was away from fashion, many realised how far ahead Klein had been. It took a while for the full appreciation of the breadth of his vision and the range of his work to be fully recognised, which is often the case with multi-talented artists who don’t stay in one lane. Stepping back into the fashion world was pretty easy, and Klein’s irony and irreverence were a breath of fresh air. In 2007, at Harper’s Bazaar, he photographed Lagerfeld surrounded by his courtiers carrying placards bearing an image of his face. It’s a surreal and almost dystopian visual gag about the cult of the “genius designer”, but Lagerfeld knew Klein and went along with it.

What was your experience curating the exhibition like?

It was great fun putting together a major survey, from the early paintings of the late 40s right up to the photographs of Brooklyn in 2013. Making exhibitions was another of Klein’s talents and there are particular ways he likes to present his work. The images are large, with no obsession over small “vintage” prints. The walls are busy and rarely white. Then, there’s the challenge of integrating his films into the scenography as well as his books. We’ve made videos of the books, so you can see every page. There are also film stills, posters, storyboards and magazines. The exhibition really has that mix of genres and media for which Klein is now so celebrated.

How do you think Klein appeals to young artists working today?

I think his self-aware kind of image-making, which is subjective but not self-obsessed or overly earnest, really strikes a chord with young photographers and filmmakers wanting to find an exciting path through the complex ethical maze of representation. Klein seemed to find his way simply by being present, accepting his place in the world and the places of those he met. He was receptive and alive to the unpredictable. To a photographer or filmmaker who lives in the moment, the world will offer those miraculous little gifts that make life worth living. That’s a great inspiration.

‘YES: Photographs, Paintings, Films, 1948–2013’ runs at International Center of Photography, New York, until 12 September 2022.

Credits

All images courtesy of the International Center of Photography