“I started adult life thinking I was going to be a historian,” says Boston-based photographer Henry Horenstein, a former student of E.P. Thompson — the author of 1963’s The Making of the English Working Class, a book considered “a landmark in English historiography”. “He taught us that the most important thing to do as a historian was to save people who would be disappeared from history.” While Henry was ultimately expelled from college, his teacher’s advice remained with him, informing much of his subsequent photography practice. In his new book, Speedway 72, the then “historian-with-a-camera in training” examines the scene at Thompson Speedway in Connecticut, a motorsports park that he didn’t think would last (in fact, it’s still active today).

In his early 20s, when he made the shift to photography, a move prompted by his premature expulsion and eased by the social norms of the time – “you could get more dates,” he recalls over Zoom, “historians weren’t too interesting” – the Speedway series arose while in grad school at Rhode Island School of Design: Henry’s brother-in-law Paul raced stock cars at Thompson, and they needed someone to shoot the weekly programme. “I’m a teacher [today, at RISD], and I always try to think, ‘what was I like then, what questions was I asking?’ Obviously it was a different era, but I think people have the same insecurities and concerns. I think I was probably trying to figure it out. I was 22, was I going to be a photographer? What was I going to work on? I started teaching at 24, I wasn’t really qualified, but I had a young woman of about 17 in the class, who was unfocused, let’s say. It was Nan Goldin, I was her first teacher. She also had no clue, she was just taking pictures of her friends.”

Publishing over 30 books since the 1970s, Henry has authored several titles for academic use and in 2016, a personal history of photography (Shoot What You Love), as well as several monographs including Close Relations (2007) and Honky Tonk: Portraits of Country Music (2003). While both were shot around the same time as Speedway 72 — the former comprises intimate portraits of family and friends, the latter covers 40 years of American music culture — the new book marks a departure of sorts, concerned with a scene Henry was only really impartial about. “I just thought as a project it was interesting,” he says, “and I thought it was probably not going to survive, the culture.”

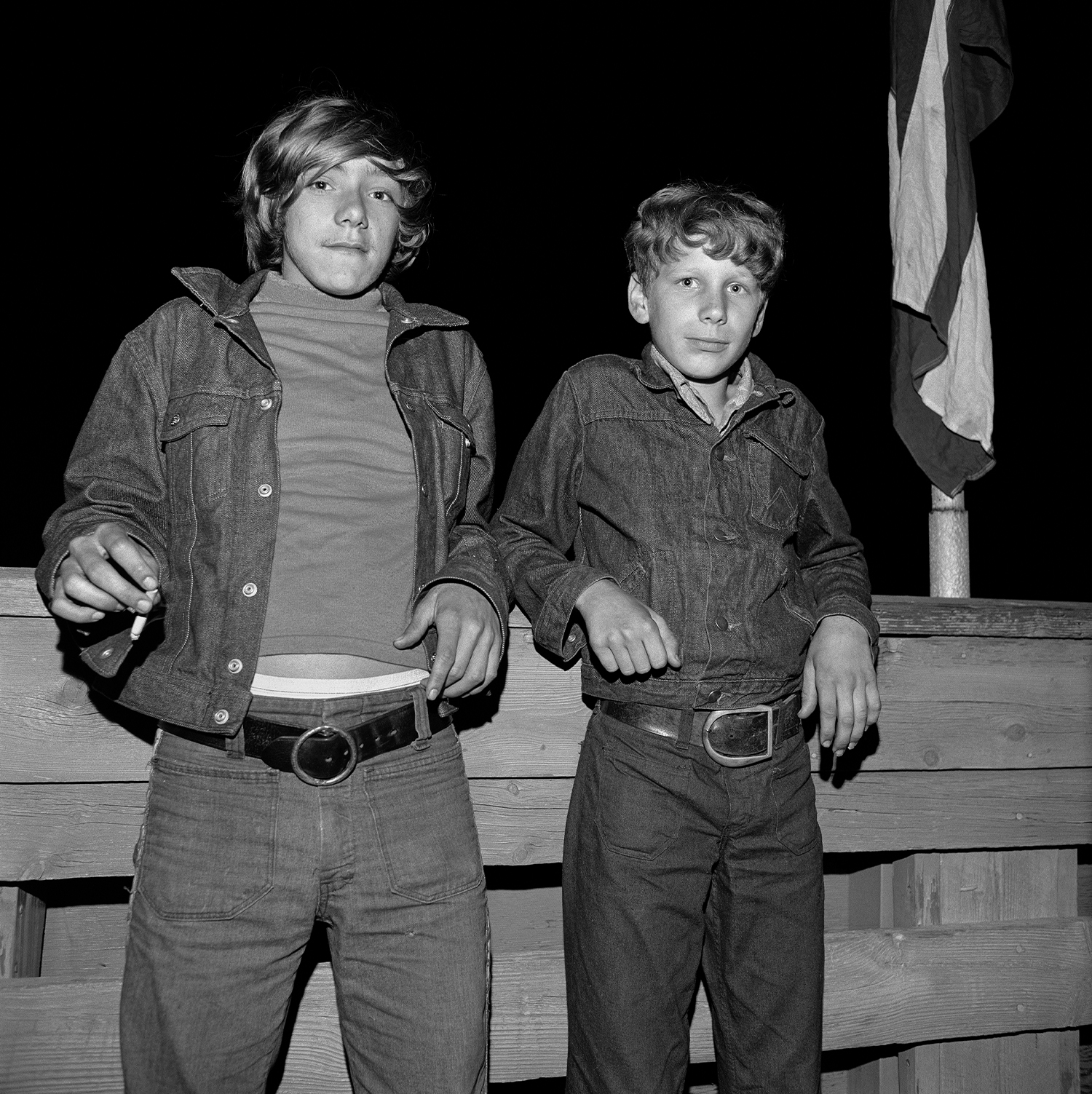

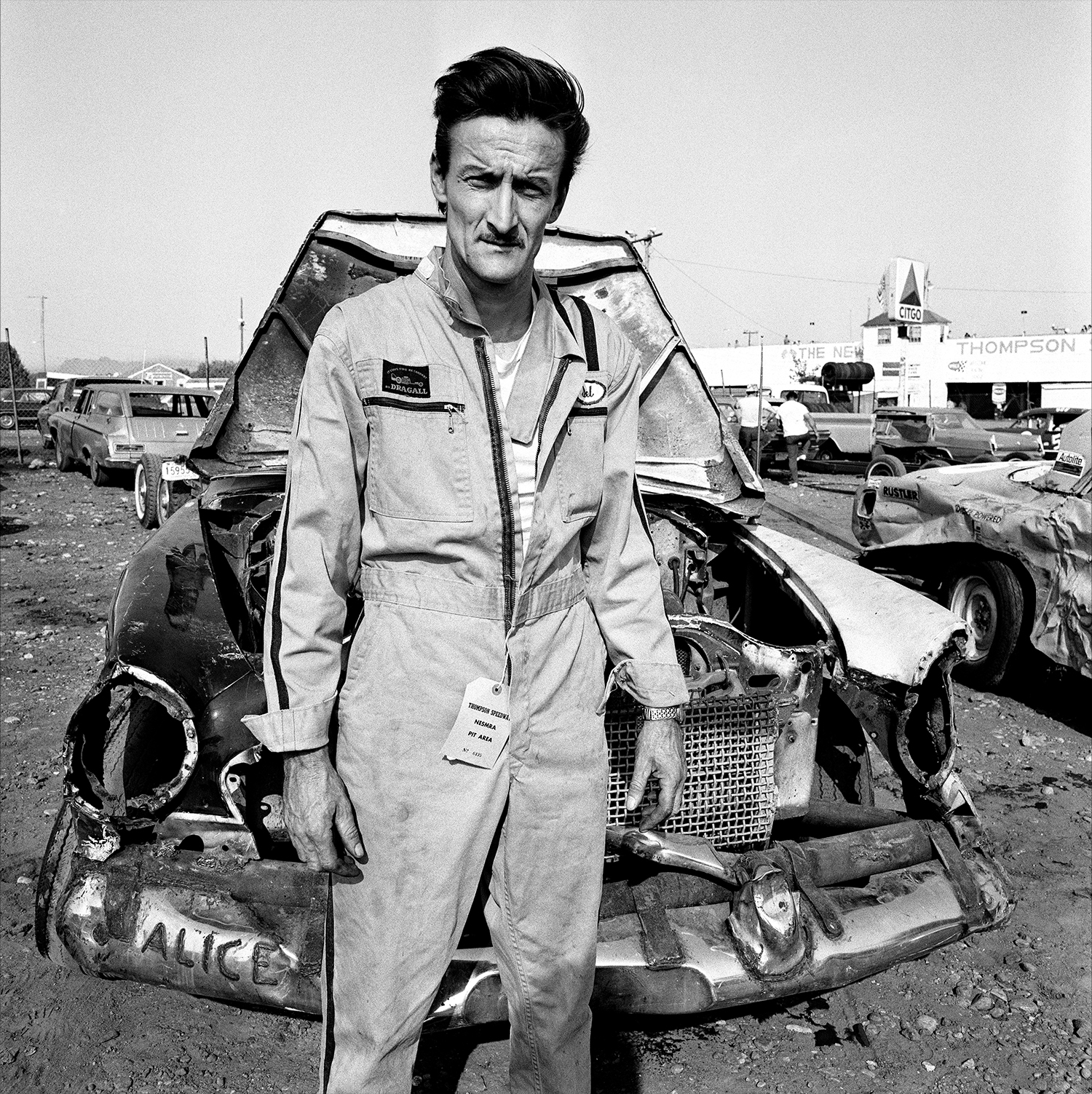

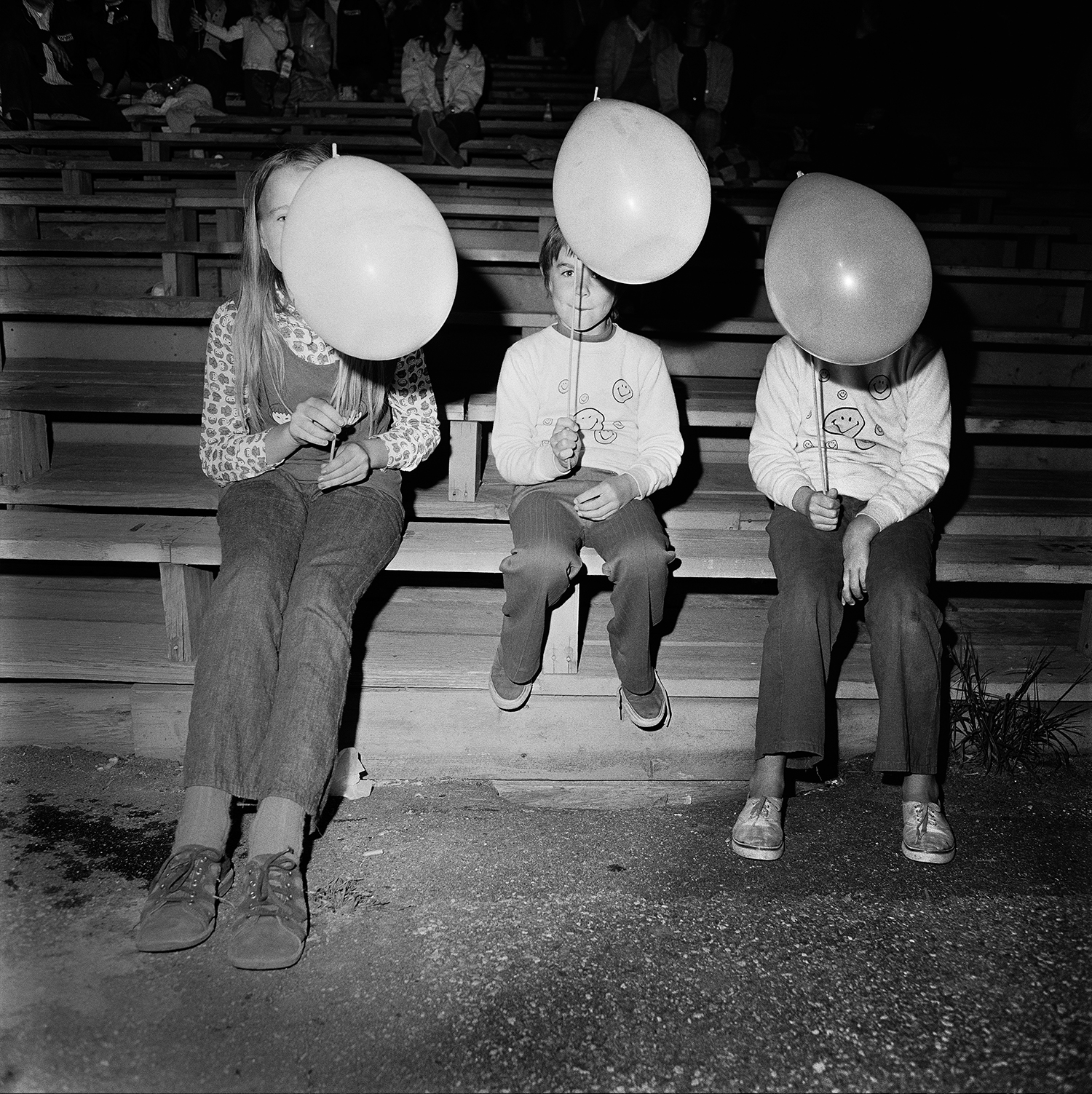

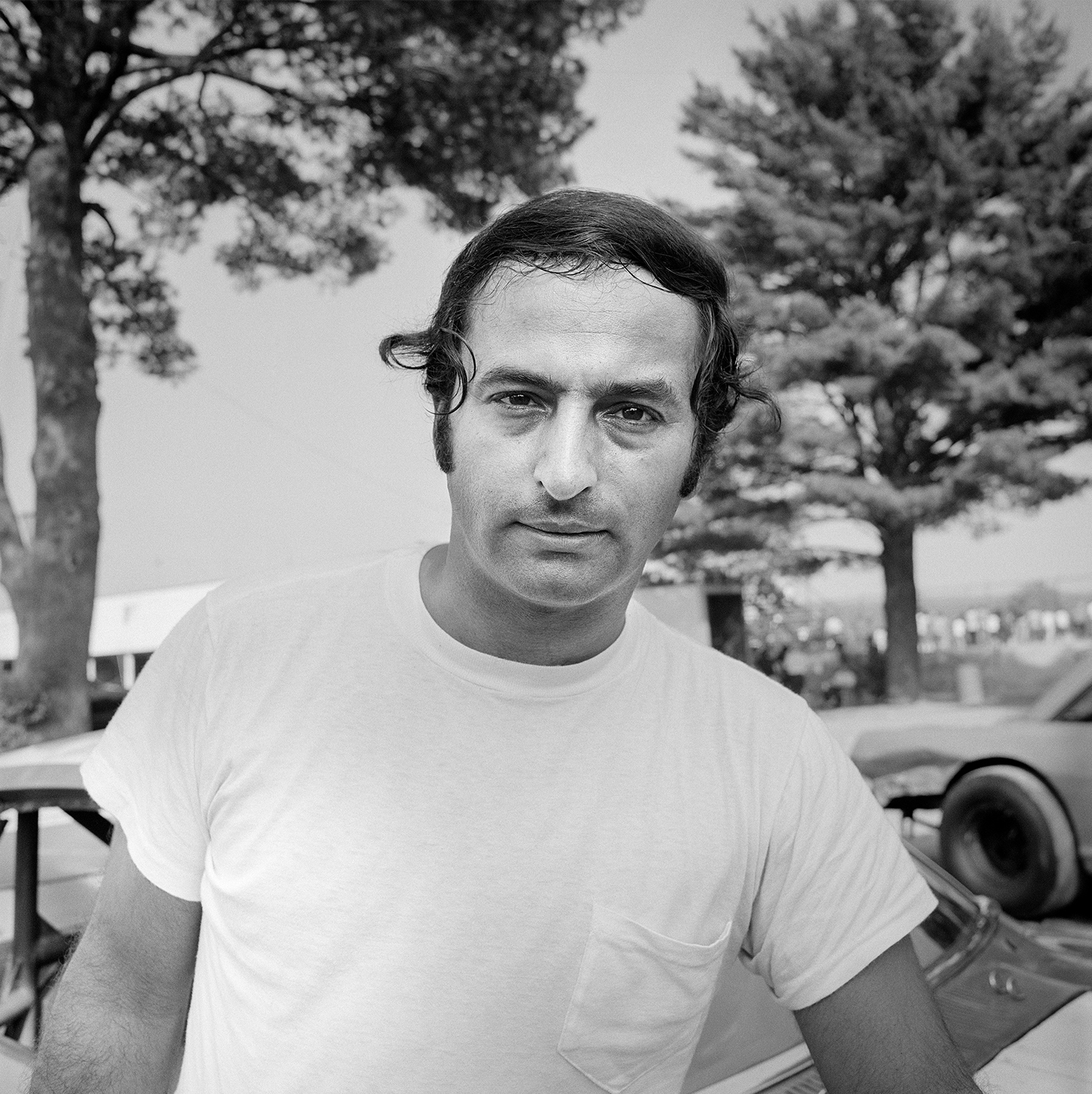

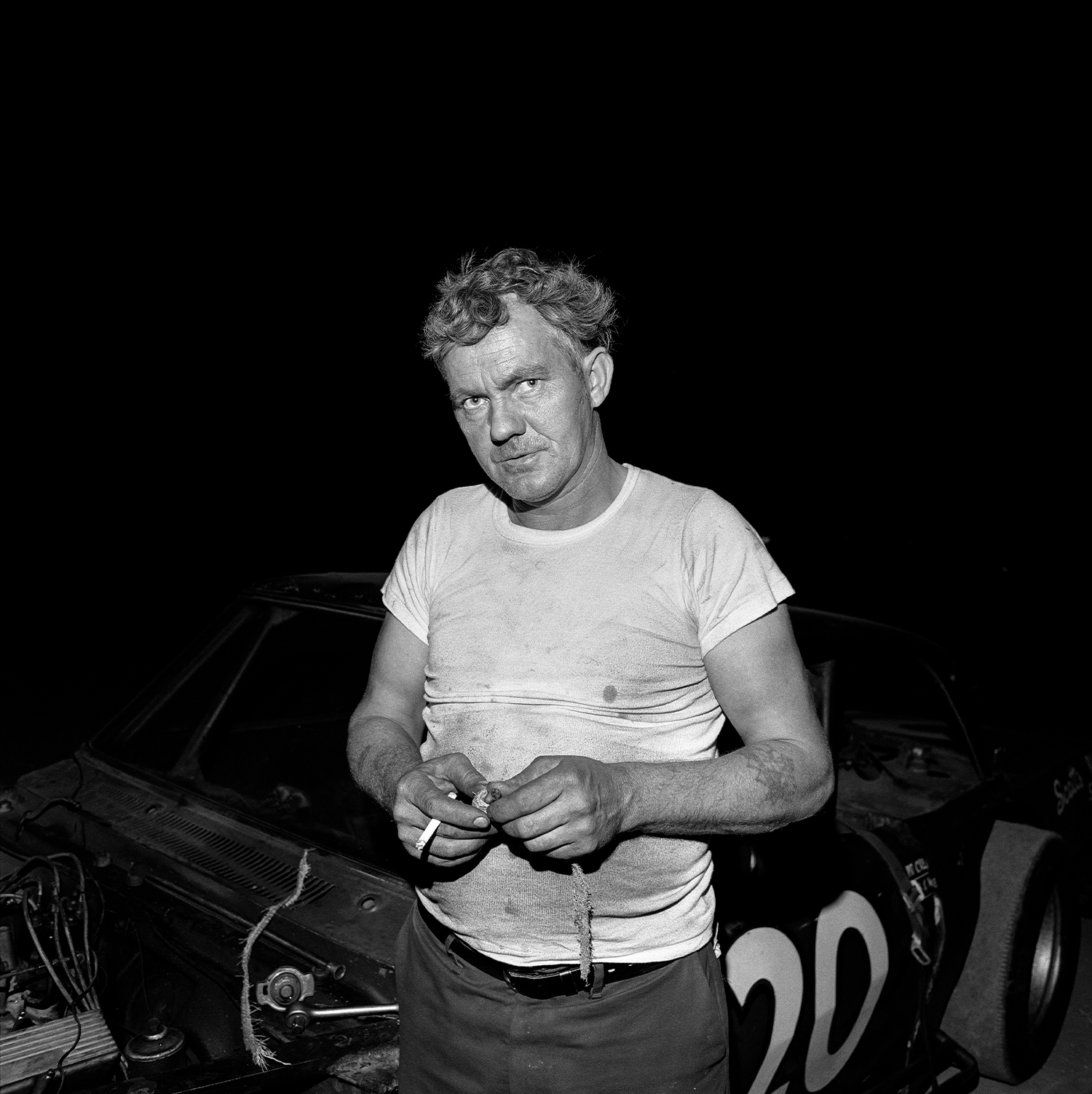

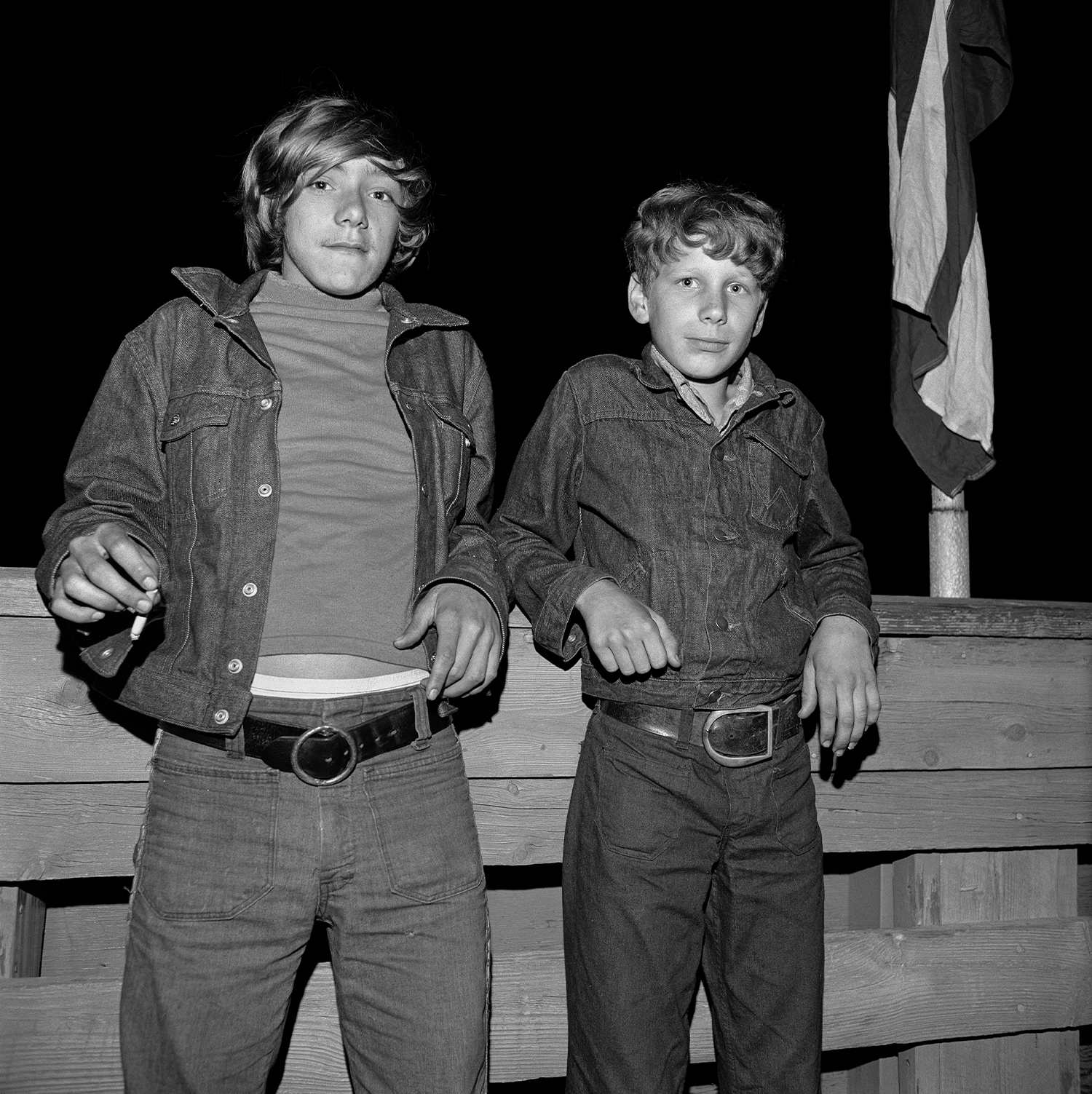

“I looked for subjects that were not being covered by other people,” he continues, relaying E.P. Thompson’s quote. “I wasn’t interested in celebrities or landscapes, I was interested in cultures, subcultures, communities that were maybe going to be forgotten down the road.” Mostly shot at night — there were very few events during the day — and exclusively produced in monochrome, in Henry’s pictures men hang out of car windows, couples wrap themselves up in blankets, and young kids play with balloons. While the vehicles are present, they’re not the focus, the photographer instead leaning into the crowds and the visceral buzz of a big day out. “It was different then, now there’s so much awareness of photography, but they were indifferent or fine [with having their photo taken],” he notes, recalling the interactions with his subjects. “Many times, they were flattered — they wanted to be in the programme.”

Published this month by Stanley/Barker, the idea for Speedway 72 initially emerged close to a decade ago, when Henry found the prints in a box while he was moving studio. “I’d kind of forgotten about them. But I looked and thought ‘these aren’t bad, this could be a book’,” he says. “I think because I came from an academic background, I thought photobooks were so cool — there weren’t many in the 1970s for a lot of reasons. One being, they were really expensive before the technology changed.”

The experiences and expectations of those he teaches has also changed in recent decades, something he considers often. “Every year there’s a group of young photographers and there’s incremental differences — things change with time of course, the world changes. When I started out, no museum showed photography. The first one was the Museum of Modern Art in New York — that changed everything in this country in 1976. I was young then and I didn’t have a plan — my plan was to keep taking pictures, to not get a straight job. I was a hippy, I wanted to make enough money to buy beer and dope, have a lot of friends and relationships,” he reflects. “Now, students have their artist statement before they have their art, they have their career strategy. I don’t think it’s bad, it’s different, it’s optimistic.”

‘Speedway 72’ is published by STANLEY/BARKER and will be available to order soon.

Credits

All images courtesy Stanley/Barker