This story originally appeared in i-D’s The New Wave Issue, no. 373, Fall/Winter 2023. Order your copy here.

When the mixes for Potter Payper’s album arrived and he first listened to the project in full, he cried. Sometimes he would be in the gym, playing the album during his workout. He would get around six tracks in and then the feelings would come, and the tears would follow. He wasn’t upset, or dejected. He was overwhelmed. To write and record Real Back in Style, he had gutted himself. He had emptied the tank and laid his life bare, tapped into traumatic emotions he hadn’t felt since jail, tussled with the label to make an album on his own terms, and given himself wholly over to the process. And so, when the songs played in his ears, he could hear more than just music. He could hear rebellion, his own resistance, could hear how he had dug deep into his history, bringing the rawest of emotions to the surface. Potter could hear the fight to make himself heard, feel everything he had poured into the fifteen songs, the 51 minutes, and the toll it had all taken on his mind.

“I was overwhelmed,” he says, “by my own resolve. You get me?”

The three years leading to this point had felt like some kind of daydream. In early June 2020, he was serving out the last few days of a prison sentence for intent to supply and conspiring to supply crack and heroin. That summer was the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. The country was on lockdown. Prisons across Britain were cracking under the strain. Inside, support services had disappeared. Family visits had halted. The gyms were closed. Education sessions had been terminated. Potter was sitting in his cell for four, sometimes five days straight. No relief, no showers, little food, prisoner A6586AM eating raw mackerel from his tin. Hungry. By the middle of the month, he was free.

Freedom was heading straight to the studio and recording six songs. Freedom was recording a music video the day after. It was the choice and the chance to pursue music relentlessly. It was releasing an EP, 2020 Vision, on June 19th, and then purging his jail diaries on the 24-track mixtape Training Day 3, released the following September. Freedom was seeing his career finally hit its stride. It was independently entering at number two on the UK album charts, with his follow-up mixtape Thank You For Waiting charting at number eight a year later. It was his own headline tour. It was the shows abroad; signing a deal with 0207 Def Jam; recording sessions in the countryside. It was seeing world heavyweight champion Anthony Joshua walk out for a title defence at Wembley Arena as one of his songs, “Purpose”, boomed out to thousands. Freedom was life-changing. It was a career, stability, all he had never had. It was finishing his first album and then sitting in the gym one day, feeling tears well in his eyes as he sat and listened back.

At this point in his career, Potter was one of the leading names in British rap, acclaimed for a stark vulnerability in his songs, a poetic vividness in his verses and brutal honesty about who he was and what he’d seen. His willingness to lay bare his traumas and his scars had forged a deep bond with legions of loyal listeners. Real Back in Style, highly anticipated and set for a May 2023 release, was as much a triumph for them as it was for him. They had followed his journey from boy to man, from mixtapes to album, listening in at his side as he lived out this new dream.

When he awoke from the fantasy it was spring 2023. Potter was back in a prison cell for a new charge that he and his team kept disclosed. Real Back in Style was due out in a few weeks. He would remain incarcerated for its release.

The first time Potter went to jail was for robbery. He was fourteen, and being dragged into the bleak orbit of an institution that would shackle his future. A path was being set out ahead, a dark road of re-offending and court dates and sentencing and then Young Offenders Institutions and HMP Feltham and Chelmsford and Avebury and Glen Parva. ‘When I was little,’ he raps on Training Day 3, ‘a judge sent me Feltham for the summertime / It made me worse, I came out and got a gun and line / And since then I’ve been in and out a hundred times’.

But before that, there was Barking. He grew up on the Gascoigne, a vast housing estate in the far east of London, bordered by Barking Central on one side, and on the other, the long A13 road that bleeds the East End out into Essex. The estate was built in the 60s, during the postwar housing boom. Terraces were razed, the tower blocks went up and the population spiked. The estate and wider Gascoigne ward would eventually house over 10,000 people. When the local factories began to close, the work went away and a range of social issues took root. By the late 90s, there were reports of low literacy and numeracy levels on the estate, high crime rates and unemployment, the Gascoigne labelled as one of the most deprived areas in the country.

Potter grew up here with his nan, his mum and his extended family. His lyrics diarise an early childhood out on the ends, encase stories of fledgling friendships: the weed his boys split and smoked four ways, the days playing out in the park till dark, the one-pound chicken and chips, the all-nighters on the number 25 bus into the city to see the West End lights. His family, like many on the Gascoigne, were not from this place. They converged here — lives moving across continents and countries like shadows, stumbling into one another by chance. His nan came from Ireland, fleeing with her children to escape an abusive partner. Potter’s dad was Algerian, his immigration story set into stone in the track “All My Life, If I Had…”

“From Algeria to Belgium, from Belgium to France, so far away from home, living life on the run / Then he made it across the border, fell in love with my mum / She was fresh from Ireland, seventeen so young / I was conceived in Barking and Dagenham you cunt / No ifs or buts, it’s just in my blood.”

Growing up, Potter’s dad wasn’t around at times, and on occasions, his mum wasn’t either. On “Purple Rain” he raps about once being told as a kid that she was on holiday, only to later find out that she was in HMP Holloway. In that parental absence, Potter and his sisters lived with his nan, raised by her and their teenage aunt.

On the Gascoigne there was music. In the deeper parts of the East End, garage had been morphing into grime, the new sound slowly dispersing outwards across the city into regions like Barking and Dagenham, the genre building atop an old legacy of MC culture rooted in the city’s working-class regions. Music wasn’t chosen, it was inherited, woven into the bricks. His mum knew a few people on the local pirate radio circuit. Sometimes she would help install aerials for a station called Temptation FM, every now and then bringing her eight-year-old son along with her to the makeshift studio. For as long as he could remember, he wanted to be an MC.

Potter came of age listening to young East London legends like Dizzee Rascal and Wiley and N.A.S.T.Y Crew, listening to early Skepta productions, listening to the older spitters on the estate and in the youth clubs. And then he started MCing himself, first on the Gascoigne, imitating the olders’ bars; then, on the first day of year seven, a big circle of kids gathered around in the playground with Potter and a few other boys in the middle, reeling off their lyrics. “I just liked the respect the older MCs got,” he says. “There was no money in it. It was just kids fucking about.”

Music wasn’t salvation — it was a pipedream, a fantasy while he began to withdraw into the cracks. There were problems at school, in the brief time he attended. There were problems at home: poverty, empty fridges, hints of drug abuse and violence, days he would beg the older kids to come back with him, because, as he once explained “if I bring friends home, then my mum’s boyfriend ain’t gonna beat her up.”

By his early teens, he was finished with education and on the streets. His family struggled to hold him in the house and, “with them failing to do that I was always going to do what I wanted.” He was doing robberies, and would soon start selling drugs. Something was catching flame in him, a hunger for more, no care of how it came about, a disregard for the consequences that lay ahead. “I need Ps. I need money. I need to have nice shoes, nice trainers, nice fucking clothes. I need weed, I need food. I need to be a G. I’m looking at all these other guys and that’s what they got, and I’m just gonna follow how they get it.”

Potter knew jail and prison would come, and still he pressed forward, not caring if he ended up in HMP. Not thinking about the addicts he was selling to — vulnerable and fragile, like himself. He would tell himself that his crimes were victimless, that “I’m just shotting,” that “if I don’t shot to them someone else is going to shot to them.” Would tell himself that, “I came up in a household of drug abuse… I’ve lived with the effects of drugs first-hand. So, if anyone deserves to make a bit of money off this, it’s got to be me.” He wasn’t surprised when, at fourteen, he was finally incarcerated.

He lost around twelve years of his life to jail, back and forth fifteen times in a period stretching through his teens, 20s and early 30s. A catalogue of these years is captured throughout his lyrics: memories of legal aid lawyers and jailhouse violence, nights on blue mattresses, nights he froze, sleeping in his clothes because the cell window wouldn’t close. Memories of trials at Snaresbrook Crown Court, of praying in a court cell for bail, of being released in 2006 and 2008 and then again in 2010, before going back inside, falling deeper into a hole.

“I knew I had my yard; I’ve got this, I’ve got that. I’m gonna go studio. I’m gonna make Training Day 3.”

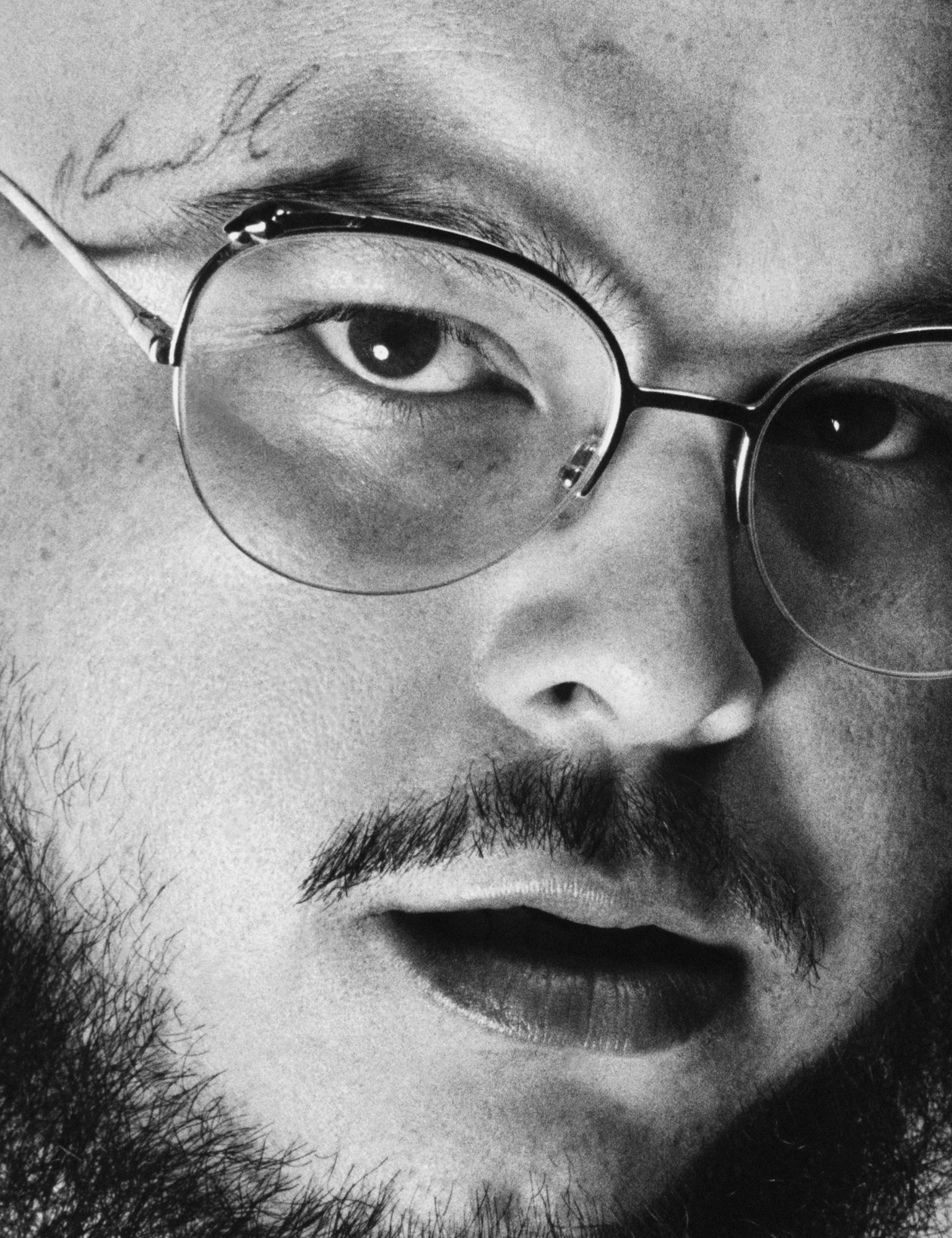

There were parts of who he is and would become that were formed in prison. It was there he got the nickname Potter because of his bowl cut and thick glasses, and was also where music and writing became a true part of his expression. Sometimes he did creative writing courses where the teachers would contrast poetry and Tupac lyrics. On other occasions, writing was a tool for survival. In jail he spent stretches on ‘basic regime’, the lowest tier of The Incentives and Earned Privileges system designed to encourage good behaviour among prisoners. Basic was for a small minority who would resist and fall short of these behavioural standards. On basic, there would be reduced contact with other prisoners, your television would be removed, and contact with the outside world would wither. It was punishment by deep seclusion. Only around three percent of the prison population were kept on the tier. Potter was among them.

“They put you in a cell for 23 hours a day and you stay in there, in that room,” he says. “So, if you can’t read and write, lord help you, you’re fucked. What you gonna do? Count the bricks or something? That’s where a lot of my initial writing came from.”

Bored in his cell, he would pick up a pen and paper and write. Some days it would be lyrics, other days it would be poetry or short stories, words falling from his mind, telling a wider story about the man he was becoming. When back out on road, he began building a buzz with music that let listeners in on the wars in his head, the wars in the street, the hopelessness of a cell, the reality of his Barking. There are stories of addicts and shotting, of shootings and traphouses, of broken families and broken spirits. Youth workers who told him he would be dead before twenty. Friends who had already passed.

But music wasn’t paying. In 2018, Potter was found guilty of conspiracy and intent to supply Class A drugs, accused of running a County Line and transporting heroin and crack out of London to the coastal town Clacton- On-Sea. At Ipswich Crown Court, he was sentenced to five years and four months in prison. It was his fourteenth time in prison. He was only 27.

During this stint, he stumbled to some of his lowest moments. A year and a half into the sentence and he was overweight, fighting with other prisoners, fatigued by it all. At times, when frustrated and resigned about his situation, Potter would talk to God and say, “this can’t be it bro. Is this all you want from me? Is this what you brought me here for? Is this what you made me born for? This life? This dead life?” Music was a dream he says, “but my reality? I’m calm with my reality. I’ve lived that reality in and out of prison, committing crime. I was a career criminal. I didn’t see nothing else. I didn’t want nothing else.”

Then there was that night in 2019, when Stormzy headlined Glastonbury Festival and many of the prisoners were watching on TV. During the set, Stormzy paused the music and began to read out a list of 52 British artists who influenced and inspired him. When Potter’s name was called the prisoners started banging on their doors, shouting his name. It lit a flame in him. He began writing incessantly in his cell and in the yard, filling up book after book with his thoughts. Training Day 3 was born from those sessions.

In one of those lyrics, he wrote ‘Now I’m looking at my daughter through this picture frame / God let me go I swear I’ll never sell that shit again’.

“That was the honest truth,” he says, “as I wrote that, I meant that.” He had made the decision to change, to wrestle control of his future, and told himself: “Rise again brudda, bring your knees to your chest. Rise again bro, sort yourself out.”

Among the most crucial moments was when Potter realised the tangible rewards music could offer. He had got a pouch of tobacco from another prisoner, and now needed £350 to pay for it. So he called his manager, Bills, to see if he could chip in. Bills told him to use his own money. When Potter said “Bro, I don’t have no money,” Bills reminded him that they had put his catalogue on Spotify in 2018. Bills checked the bank account and rang Potter back, telling him there was £50k in there. Unsure if the funds were real, Potter sent a chunk of money to his nan, and then asked his little sister to go to a petrol station and make a withdrawal from her account. When she confirmed the money was there and real, he paid the guy off for the tobacco and then, for the rest of his sentence, didn’t touch the account. He was leaving it to accumulate for when he got out.

“From that point up until 2020 was pure training, planning, straightening my relationships with my family, trying to do wholesome things and to be a better person. Reading more, stopping getting drawn out into silly little situations,” he says, “enforcing that on yourself and forcing your peers to be comfortable with that. After a few years of that, I was ready to come out and smash it.”

The streaming money meant that he wasn’t hustling to survive anymore. He had breathing space, and could look beyond the day ahead and out into the future. When he was released in June 2020, Potter wasn’t starting his life over, and wasn’t thinking, “Where am I gonna live? How am I gonna live? How am I gonna get about? What am I gonna do?” he says. “I knew I had my yard; I’ve got this, I’ve got that. I’m gonna go studio. I’m gonna make Training Day 3.”

“I suffered to convey this message. Not to be ‘this rapper’, ‘this rich guy’ or something like that, but this message in the music. Whatever is getting people saying to me ‘you stopped me from this’ or ‘you helped me through this.’ That’s what it was for.”

With the success and freedom that would follow, it felt as if one, dark chapter of his life had finished, and a brighter dawn was opening out ahead. There was learning. There was growth, and evolution. It was challenging. He had to surround himself with the right people, and stay away from Barking because “that’s a dangerous place to be. I ain’t tryna go out like Nipsey, I ain’t tryna go out like all the greats who still stayed around in their areas and ended up, you know.”

There was loss, too. His aunt passed, and so did his nan. Potter tattooed her signature above his right eyebrow. He kept on working, relentlessly pushing forward with music and everything else. He signed with 0207 Def Jam, started putting out music on his own label, released two mixtapes and two accompanying documentaries, and finished his album. Its approaching release felt like a victory lap, a crowning moment for a man who had overcome the devil on his shoulder, whose hundreds of thousands of listeners had watched him make a climb out of the darkness. It was bigger than him. A line on “How Can I Explain?” captures the mood: ‘Now I’m free to make a living, God knows I’m grateful’.

During Potter Payper’s stint in jail earlier this year, the album debuted at number two on the UK album charts. He was released later that summer, bringing his fifteenth sentence to a close. When we sat down and spoke, he said, “I’ve just got to keep making sure that I’m not doing nothing, then they can’t do nothing to me. Even if they arrest man, or send man jail they’ll never be able to convict me of nothing because I don’t do nothing.”

There is no straight road. There is difficulty in the walk. When you have been where Potter’s been, the past never leaves you — and it appears at unlikely moments, intent on dragging you back to what once was. There may be more of these moments in his future. And yet, despite what he has lived, there is little he would change.

“I’m very mindful that the position I’m in is not by accident,” he says. “I suffered to be this, to convey this message. Not to be ‘this rapper’, ‘this rich guy’ or something like that, but this message in the music. Whatever is getting people saying to me ‘you stopped me from this’ or ‘you helped me through this.’ That’s what it was for. That’s what I went through all of that for, to be able to convey that message.”

And so, he moves forward, away from a version of himself that some still define him by, moving forward, carrying his freedom in his hands while his past looms large in the shadows.

Credits

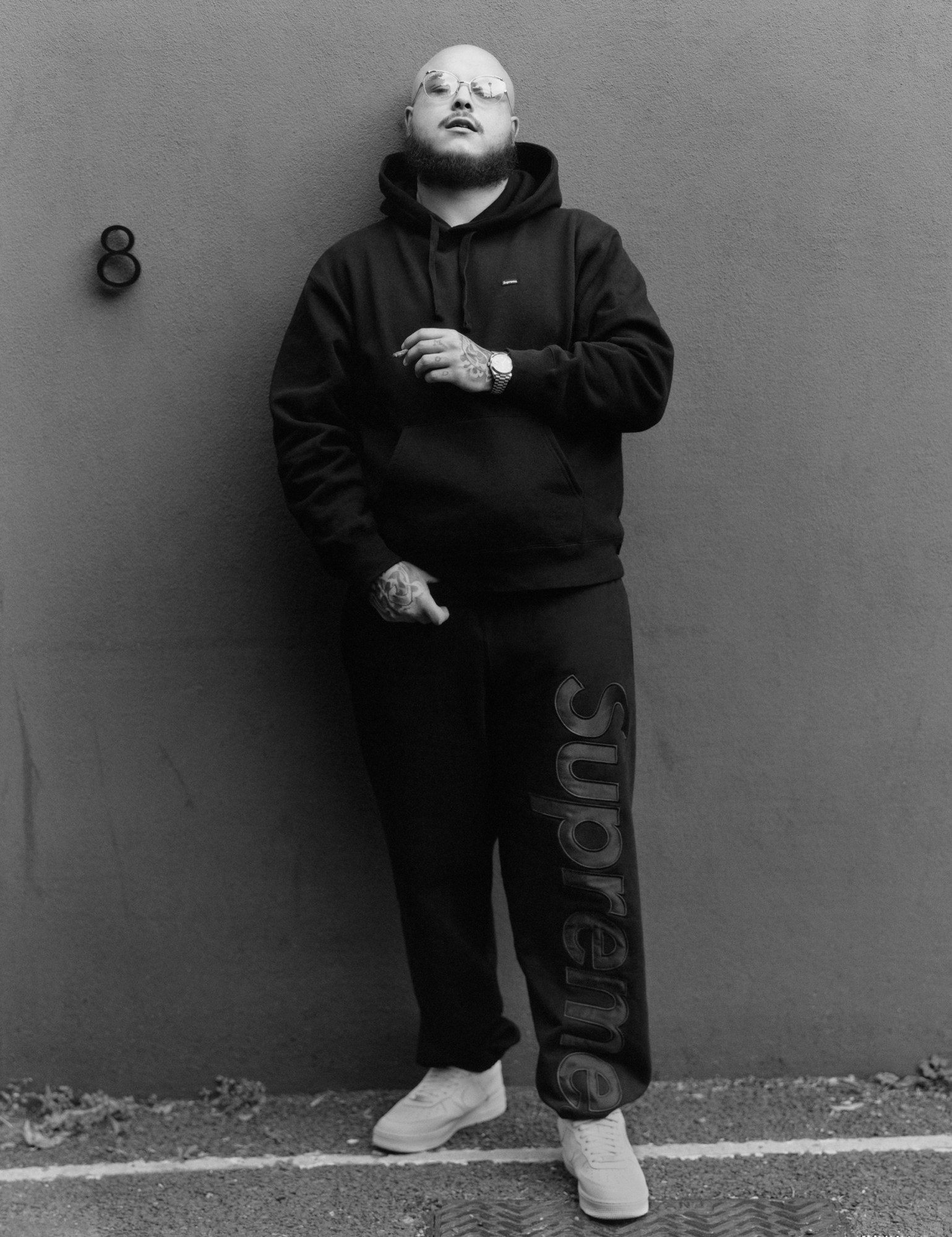

Photography Maxwell Tomlinson

Fashion Louis Prier Tisdall

Grooming Nat Bury at Leftside Creative

Lighting Assistance Andrew Moores

Hand Prints Dot Imaging

Retouching Lasso Studio

Potter Payper wears all clothing SUPREME. Glasses (worn throughout) CARTIER. Watch model’s own. Shoes NIKE