This story originally appeared in i-D’s The New Wave Issue, no. 373, Fall/Winter 2023. Order your copy here.

It’s early July when Sampha announces a pair of London shows at Hackney Church. Satellite Business… a place to explore again… if you’re interested come join us. My group chats and timelines are flooded with the same notions, the same questions: ‘Are we getting tickets for Sampha?’ ‘Will we secure tickets for Sampha?’ I miss out on the initial drop but somehow, through a little luck and manifestation, end up with a pair of tickets. Somehow, I’m making the journey from South East to North East, towards the church, wondering what we’re about to experience. Somehow, I’m standing shoulder to shoulder in the swelter of the space, all of us sweating as we wait for Sampha. As he emerges with his band, into the space in the centre of the church, all of us circling him; as he begins to perform, playing songs we know all the words to and songs we’ve never heard. As the spirit really begins to take him, a bend in his knees, the bop of his head, each vocal utterance reaching towards something higher, something more, all I can think is that this was worth the wait.

A few months later, Sampha opened the door of his studio to me. Despite the fact the 34-year-old is from South London, by way of Sierra Leone, I’ve always thought of him as a global citizen, due in part to his wide reach. In addition to 2013’s Dual and 2017’s Mercury Prize-winning Process, Sampha’s voice and production can be heard on Stormzy’s This Is What I Mean, FKA Twigs’ LP1, Travis Scott’s “MY EYES” and Ragz Originale’s “BARE SUGAR”. Elsewhere, on Solange’s A Seat at the Table, Frank Ocean’s Endless, and more recently, a scene-stealing feature on Kendrick Lamar’s Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers. This broad list speaks not just to musical dexterity, but a talent and openness which transcends space and genre.

When we speak, we’re in his studio near Islington, North London. He’s quiet and watchful but immediately warm, fussing over me a little, finding me a comfortable chair for our conversation, asking if it’s ok if he completes his ritual on entering his workspace: burning a stick of palo santo, cleansing his space. He apologises for the mess, but it’s the kind of mess I like, where you can see and appreciate the mind’s beautiful scatter: his instruments from touring are boxed up and spread around the back of the studio, towards the front, around his workspace I spot the distinct blue of a Noah Davis book of paintings I also own. Splayed open by a synth is a Liz Johnson Artur monograph. When we finally settle down, I ask him, “how is your heart?”

He’s thinking about the release. It’s been a minute—at the listening party, Sampha jokes that the record has been in development since around 1990; his last album, Process, came out in 2017 — and the landscape of music and the way we consume media has changed. The demands outside of the creative process have also shifted, with touring taking on more importance alongside the necessity of some sort of social media presence. So, he’s thinking about the release, specifically around how listeners will connect with the album — “how a collective consciousness might meet this piece of work.” Which makes sense for an album that feels as communal as it is driven by a singular voice.

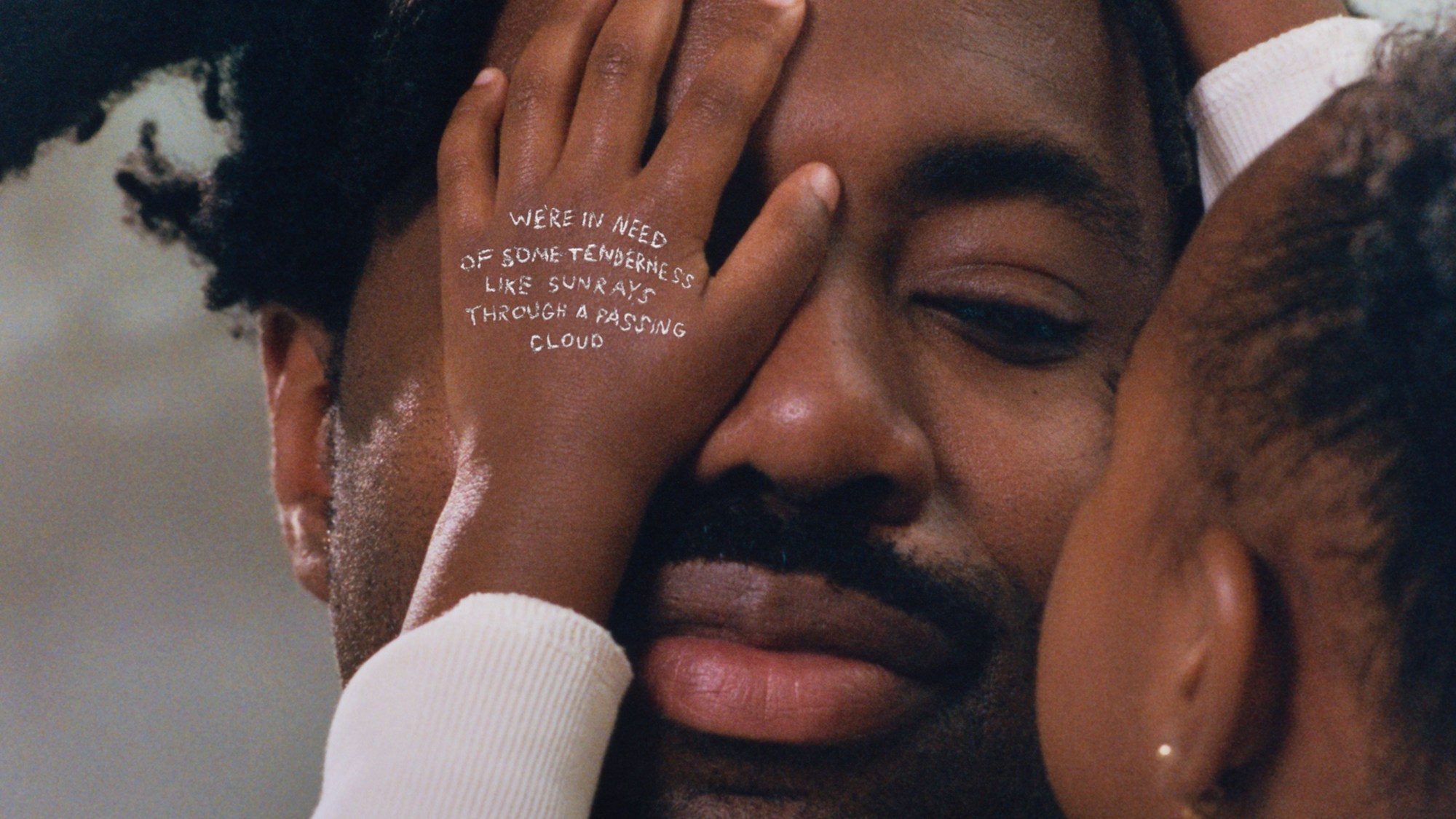

Still, I don’t think he should be worried. By the time we meet, I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve listened to his new album, Lahai, named after his late grandfather, a name Sampha also shares. I’ve played it out loud at home, letting the music wash over me, on long car journeys on my own tour. It’s a gorgeous, expansive record which, from the opener of fourteen tracks, invites the listener to travel with him across time and space, to ask questions of our place in this world, of the ways we love and our need for tenderness in the everyday. It’s a record which encourages time to stop, encourages you to be present. Encourages you to be with yourself, whether that’s alone with headphones pressed to your ears, or on a Thursday evening in a church in Hackney, standing with a community of people for whom music means everything, too.

The inception of Lahai arrived in late 2019. Sampha was working, working on many tracks which didn’t end up on the record but were in line with the sound which would become the spine of the album. Much of his process is reliant on feel and so when that feeling arrived, that oft-elusive sense which artists are striving towards: an opportunity to sit with an honest version of the self, too, as he sings, “gift my feeling language”, he had to go towards it. When I ask him how he knew, he says, “you just do. It’s the feeling, really trusting that feeling.”

One of those early songs would become “Spirit 2.0”, an ecstatic, glitchy number where the drums and synths create a harmonic sonic bed for Sampha to croon over. Once he had this song, once he had that feeling, he planned to hunker down and get the album.

The world had other plans. 2020 arrived, and with it a global pandemic. A shift in the way we were, in the ways in which we were connected. Many of us who were working and living within a chorus were severed down to solos. During that time, Sampha’s partner fell pregnant. It was an intense time, he says, but rather than fold, it was a time to reconsider. Rather than his original plans of flying over here, and doing sessions there, many of the tracks came together in his flat, usually in his bedroom. It makes sense. Despite the fact it feels extraordinary in scope, there’s still a warmth and intimacy which arrives and mirrors those moments of inception.

Like much of his work, the music started where he’s happiest — freestyling at the piano. It was one of the things which struck me on my first listen, the improvisational quality of a record which still manages to maintain an incredible cohesion and harmony. He also wanted to challenge himself to be more conceptual, which this time round, involved recognising what he was gravitating towards, and kept returning to.

When I ask what these were, he sits back in his chair, pausing for a moment before reeling off those curiosities: time as a constant; the way it flattens, pulls, shrinks, glitches and stops altogether; the way it relates to mortality. The bird too, is a constant image, a constant presence. “Flying and the feeling of it… I got into wondering what it would feel like to have the wind blowing in your face, what it would be like to be a bird, to translate that feeling,” he explains. The natural world and its beauty. Transcendence. Having a daughter and family, recognising himself in the bigger picture. How all these strands can come together to act as a document for those moments, for the time. How the record was allowing him to see things.

“What could you see?” I ask.

“Myself,” he says, nodding. “The things I’m preoccupied with, dealing with. Yeah, I saw myself.”

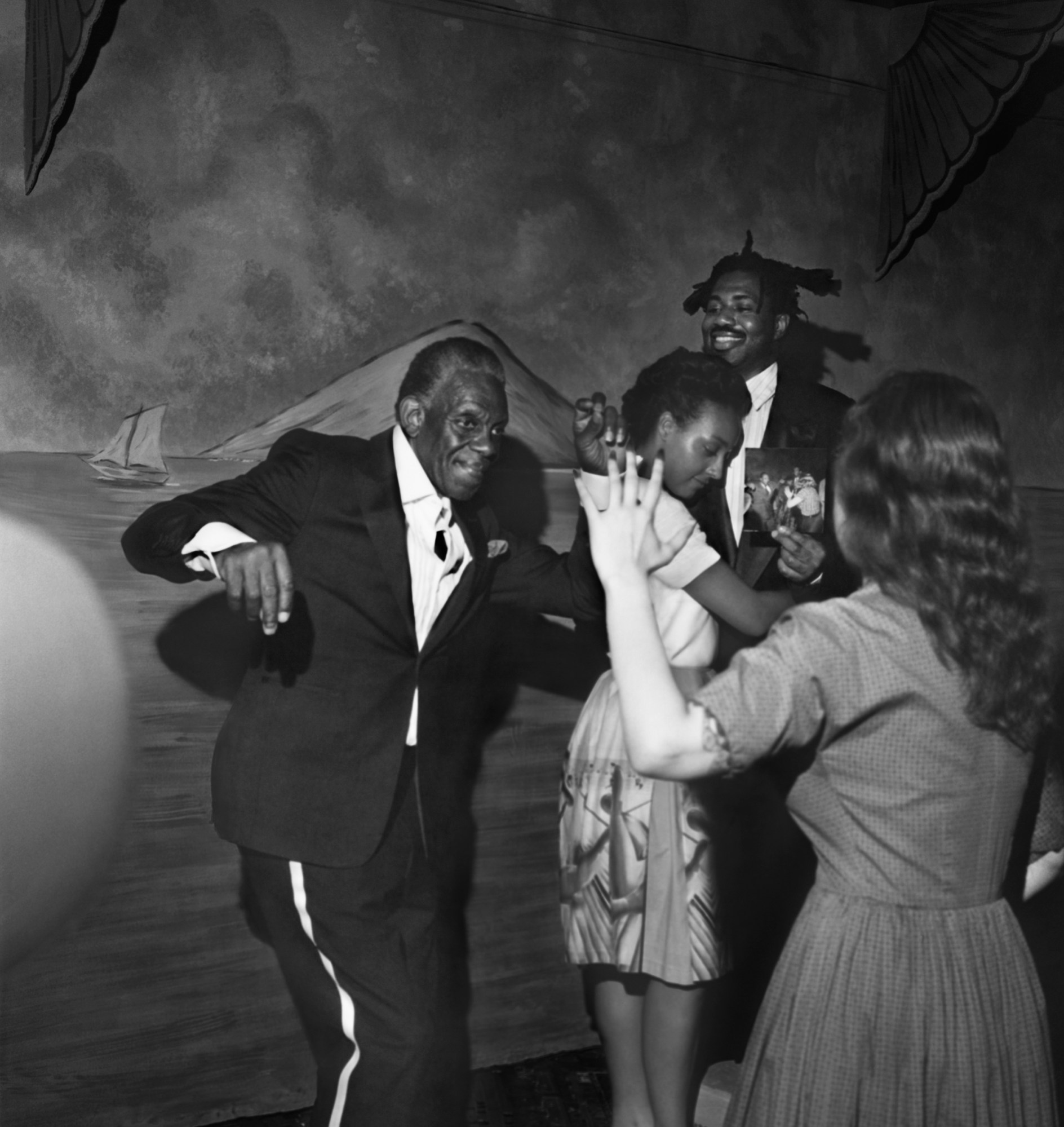

With that self that he’s seen—“they aren’t different, both just versions of me”—he’s been trying to approach his own vulnerability. We speak about him trying to get out of his way when he performs, letting go of himself to get into himself. I’ve witnessed his (successful) efforts firsthand, at the recent show, where he looked so carefree in his motion. Dance is a beautiful space. Regardless of the witness, the dance is always yours, a time to be loose and limber with your body and self, even if it’s just for a moment.

So much of this opening up to himself was down to his list of collaborators for this album, which includes Ben Reed, Kwake Bass, Mansur Brown, Yussef Dayes, Sheila Maurice-Grey, Riccardo Damian, Léa Sen, Lisa-Kaindé Diaz of Ibeyi, Yaeji, Kwes, Laura Groves. Much of this extensive list were natural connections, people he has long-standing relationships with, people who were coming in and out of the studios, participating in jam sessions which lasted days and helped mould and shape Lahai. Much of this list are also London-based musicians, which we both agree adds a certain texture to the music, one you can always sense, if not articulate. A big part of that has to do with the diasporic nature of the community. How many of us are from somewhere else — West Africa, the Caribbean and beyond — and carry this elsewhere with us. What we’re hearing on Lahai is what happens when influences, often things which have been passed down to us from parents and grandparents, meet with someone else’s influences, the space that makes. What happens when Sampha’s love for Wassoulou music — a huge influence on the album, he says — meets Yussef Dayes’ drum & bass pockets and sensibilities? What happens when Sheila Maurice-Grey’s or Mansur Brown’s jazz influence is thrown into the mix? The record grows, and the vision expands. Beauty emerges.

In addition to this, Sampha feels he and his collaborators were participating in some form of communal Afrofuturism. Everything they were expressing was asking the question of what it means to be diasporic, this feeling of alienness which often arises. But running both parallel and counter to this notion, he was interested in what happens when you gather people; what happens when soloists form a chorus; where there’s a handful of mics in the room and a real energy and intention? What happens when you gather a group of people who know what it feels like to be diasporic, to be alien. Can that feeling be transcended?

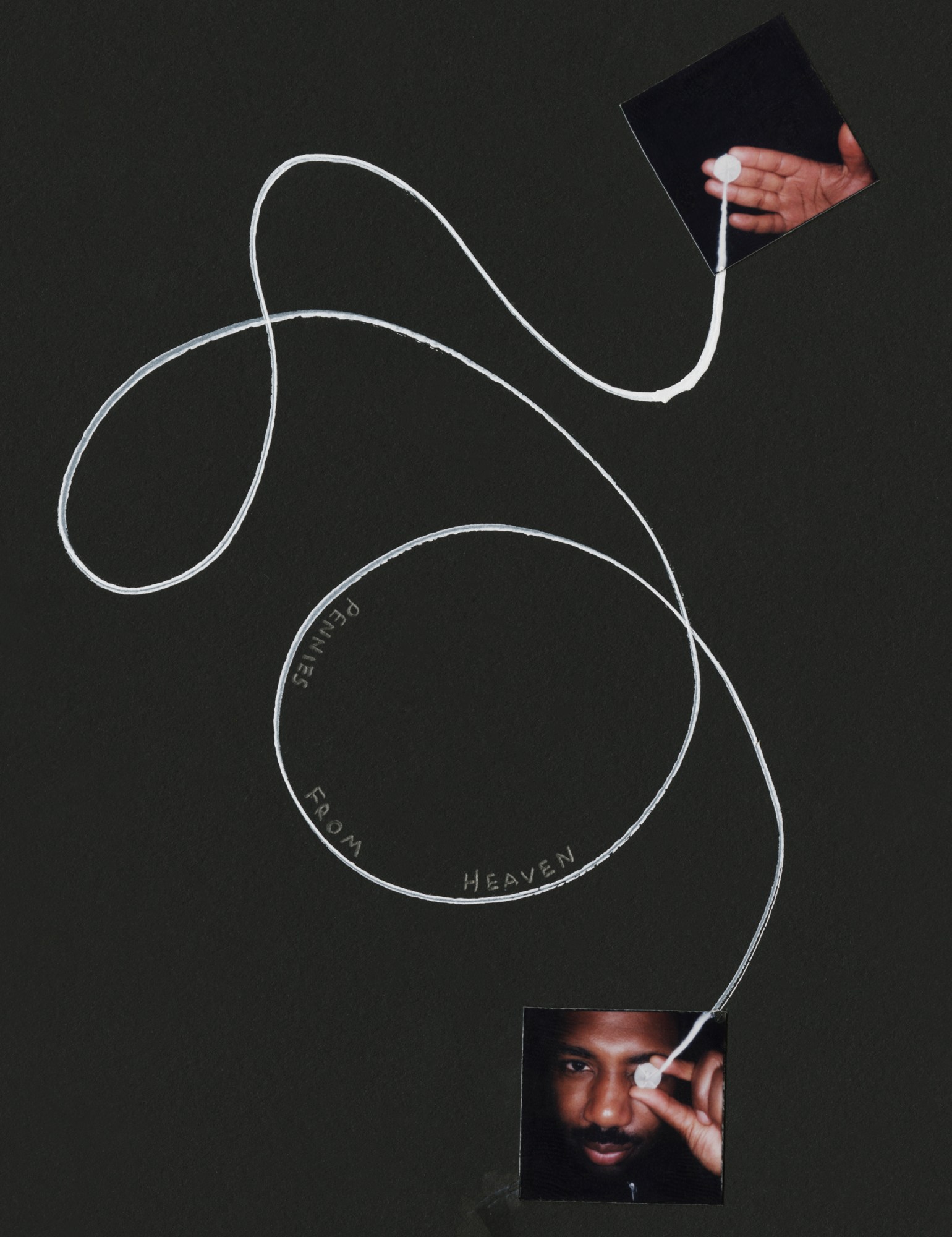

Sampha’s immediate community has grown, now that he has a daughter. He couldn’t articulate what becoming a father did to the record at first, but he could feel the influence deeply. As the creation of the record continued, old griefs began to resurface. Not just because he was thinking of the new life in front of him, but also because he could see others in her, like his mum and grandad, those who were no longer with him but who were still present in a gaze, in movement or motion, those small nuances which make us who we are. Now, a month or so away from the release of Lahai, he can see how fatherhood has encouraged a patience in the music, with others, with himself. It’s encouraged him to want to be better, now that he’s responsible for someone else in this world. It’s encouraged him to be more grateful for the women in his life, of whom he says the deep love and patience and care they have, were a clear presence on the record.

As he speaks, I’m reminded once more of the listening party held at Young Space, the week before he and I spoke. We were all sat on cushions spaced about the place, having already been fed on entry, asked if we needed anything to drink. We were already deeply immersed in the music playing from a beautiful hi-fi setup at the front of the room, when, somewhere in the gap between the first and second song, Sampha’s deep, sonorous voice emerged.

“Is the music too loud?” he asked.

Many of us shook our heads. Many of us said something along the lines of, ‘no, it’s perfect’. Many of us smiled at this man, with a deep consideration for his community, with a love and care that is all over the music. Sampha surveyed the room for any objections, and when none came, he nodded, smiling to himself, letting the beauty of his creation fill the space, letting the music play on.

Credits

Photography Frank Lebon

Fashion Tom Guinness

Hair Takuya Uchiyama

Make-up Athena Paginton at Future Rep using Fenty Beauty and MALIN+GOETZ

Set Design Arthur De Borman at Magnet

Photography Assistance Rory Cole, Beatriz Gonçalves and Dylan Massara

Fashion Assistance Archie Grant and Eibhilin Moores

Set Design Assistance Ted Pearce, Roisin Jenner and Rosie Kidd

Production Dobedo

Casting (models only) Sarah Small at Good Catch

Models Johnny Mitchell, Emma Zarifi, Grace Davey, Claudia Celeste, Christopher Lilleorg, Freddie Mackenzie, Solomon Robinson and Titas Mackevičius