For Stacy Kranitz, confronting the complicated tradition of documentary photography means reckoning with a long history of colonialism and capitalism. The question of how these three forces intersect to exploit vulnerable populations shapes her practice, which, at its core, calls attention to the medium’s limitations by subverting what we inherently perceive as true or false. “The threshold for what kind of photography is sensitive or insensitive isn’t just about the photos,” Stacy says. “It’s also dependent on personal experience or someone’s relationship to poverty and class. The concept of poverty porn is vague, and that’s really interesting to me.”

Stacy discovered her love for photography in college, intrigued by its immediacy and how she could simply step outside with her camera, into a world of infinite possibilities. Once she graduated, she juggled gigs as an assignment photographer for different magazines and newspapers, a job she maintains with current clients such as National Geographic, Vanity Fair, and The Atlantic. Still, even after a few years in the industry, something seemed amiss, causing her to feel disillusioned with her creative work. In 2010, she decided to pursue her broadest project to date, setting her sights on the rolling hills and Smoky Mountains of an often misunderstood terrain.

“I took a step back to see what I really wanted from photography,” Stacy says. “I realized my work had been living on the surface of an idea and I wanted to make work that lived the actual idea.”

Over the last 12 years, Stacy traveled through parts of Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia to examine how photography can reinforce and debunk deep-rooted biases. Rather than portraying Appalachia as poverty-stricken or selectively focusing on its positive aspects, she sought to capture the complexity of rural, working-class life from a nuanced viewpoint. “Something about asserting right and wrong onto a work inevitably makes me hate it,” Stacy says. “Photography best illuminates societal problems when it exists in an ambiguous place.” As It Was Give(n) To Me, a monograph available for pre-order through Twin Palms Publishers, follows her exploration through a collection of 187 candid color photographs, some of which are accompanied by drawings, maps and other ephemera.

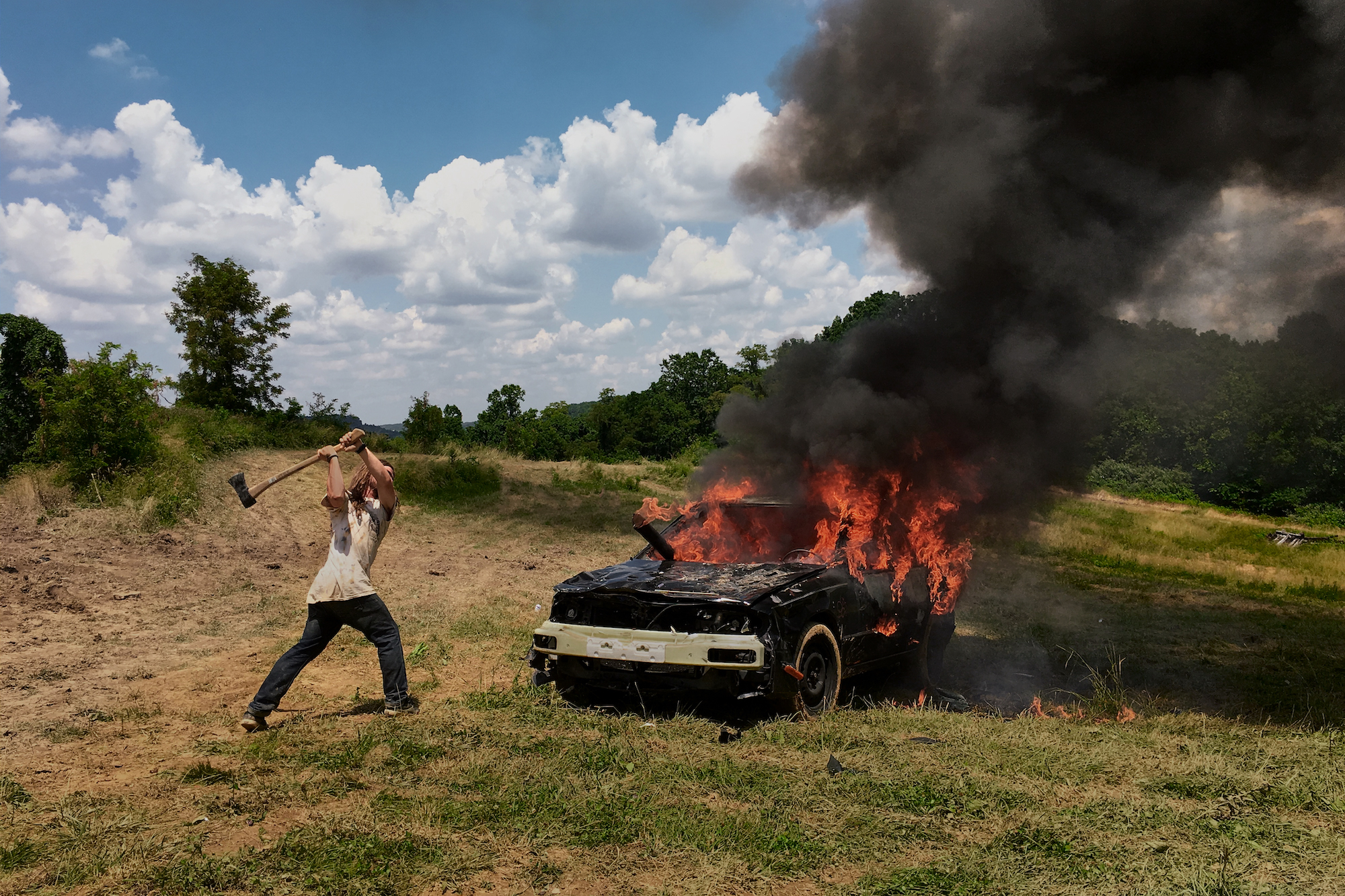

Recalling a classic colonial chronology, the book is divided into multiple chapters: Arrival, Exploration, Extraction, Mutiny and Salvation. Stacy modeled this narrative structure after a catalog of paintings about Daniel Boone, a frontiersman who encouraged westward expansion into present-day Kentucky and incessant brutality against Native Americans. As It Was Give(n) To Me features similarly frenetic pacing, beginning with calmer images like children riding bikes in ‘Arrival’ and culminating in ‘Mutiny,’ which captures cars ablaze, women rolling in the dirt and other hectic scenes. Interspersed clippings from a weekly column in The Mountain Eagle, a Kentucky newspaper, share anonymous opinions on anything from the opioid crisis to political polarization or systemic discrimination in healthcare.

“If you take mining out of here, do you think Walmart is going to stay?” one passage asks. “Do you think any of these places are going to stay with just minimum wage jobs? You better thank a miner, because without them this place would be a ghost town.”

Appalachia started experiencing the detrimental effects of coal mining in the 19th century, after the industry stripped the region of natural resources and left indigenous inhabitants landless. Standards of living had scarcely improved when President Lyndon B. Johnson declared a “war on poverty” during his 1964 State of the Union address, prompting a slew of government-funded programs to reduce economic scarcity, enrich society, and uplift those whom the American Dream had excluded. Appalachia became ground zero for the initiative. Journalists and news crews swarmed the region, ultimately typecasting its inhabitants as down-and-out or undignified. While many of these programs have now seen severe reductions in aid, the cruel stereotypes continue to haunt locals like a specter of shame.

“I was drawn to Appalachia because I was interested in the failure of objectivity, specifically looking at a place where photography had failed the people it was trying to help,” Stacy says. “I wanted to make work that both critiqued and celebrated the documentary tradition.”

As It Was Give(n) To Me doesn’t attempt to rewrite this problematic past or rectify present circumstances. It offers an honest glimpse at an ideologically diverse region, juxtaposing pictures of public school teachers wearing face masks with men flaunting the Confederate flag. Fascinated by the blurred separation between art and life, Stacy was more than a mere observer during her journey. She befriended some of her subjects over an extended period of time, partied with them, and did drugs with them, fully immersing herself in the circles she captured. This could explain why so many images look casual, shocking, and intimate, like couples canoodling naked in a hot tub or having passionate sex on a dryer. Everyone goes about their business as usual, outwardly relaxed in front of the camera.

“My understanding of agency, consent, and the complex power dynamic between photographer and subject is always changing,” Stacy says. “Developing deep bonds with the people I photograph is the central reason I continue to pick up a camera and engage with strangers. The experiences I have are far more interesting to me than the pictures themselves.”

Documenting the shifting landscape of Appalachia has also allowed Stacy to reflect on her role as a record-keeper, in preserving certain moments or places long after they’ve vanished. One somber shot shows a large, abandoned treehouse in Crossville, Tennessee, originally built in the 90s by a local minister, Horace Burgess. Over the years, the structure assumed many forms, its first incarnation being a church where Burgess held Sunday services. Safety code violations eventually shut the space down, but it was later reborn as an illicit hangout spot, its multi-level structure the ideal layout for an all-night rager. Then, in 2019, catastrophe struck when the treehouse caught on fire. It burned down in less than 15 minutes, destroying a piece of history in the process.

Only debris and memories remain today, reminding us that an image’s significance can change over time. As she grew more familiar with the multidimensional region, Stacy evolved as well. It might be easy to miss her self-portraits scattered throughout the book, reimagining herself as Christy Huddleson, the protagonist from Catherine Marshall’s 1967 historical fiction novel Christy. Wearing a flowy blue prairie dress in one picture, Stacy stares intensely at the camera, her presence shattering the illusion of impartiality. She’s cultivated her own unique connection to Appalachia in the last 12 years, and hopes As It Was Give(n) To Me will spark a conversation about how marginalized communities continue to suffer, their struggles so frequently ignored.

“I see photography as a triangle between subject, photographer, and viewer,” Stacy says. “You don’t need to know every reference to appreciate or value it. I tried to create a book with multiple entry points because I want viewers to find their own way through these images.”

As It Was Give(n) To Me is available for pre-order from Twin Palm Publishers.