Ewen Spencer isn’t as sentimental as you might imagine a seasoned chronicler of British youth culture to be. “I’m quite wary of nostalgia,” he says. “As an idea. It feels like the end.” It’s worth remembering this when diving into his back catalogue and the misty-eyed rabbit holes they lead you down. Lost London blogs where Northern Soul disciples reminisce about venues; YouTube spirals leading to Mark Leckey interviews and early grime demos; DIY retailers flogging Ellesse tracksuits à la eighties Football Casuals. It’s a disparate cultural inventory, held together by romance and memory for some, but for the majority who weren’t participants themselves, via images.

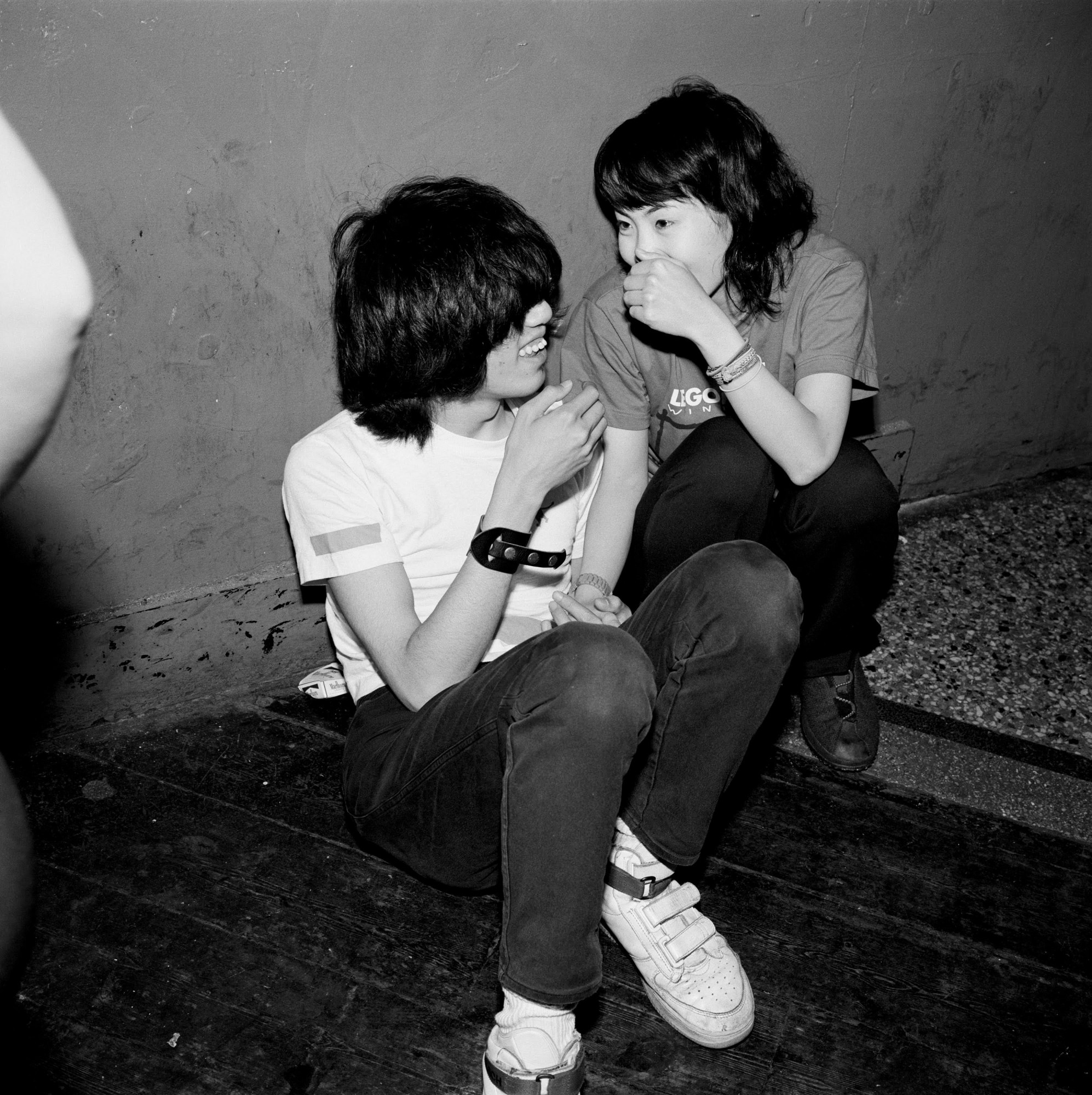

Ewen’s photographs depict the soundtracks and uniforms of Britain’s youth from 1997 to today, captured in clubs and street corners before being beamed to a captivated public. First in Sleazenation and The Face magazines, then in his influential photobooks, films and exhibitions: Open Mic and UKG (on grime and garage, respectively); Young Love; Brandy & Coke; Street, Sound and Style (made in collaboration with i-D) and now, While You Were Sleeping, a selection from the thousands of images he made travelling around UK nightclubs between 1998 and 2000.

Early on, Ewen would shoot whichever scene he himself was involved in. In 1997, as a recent graduate of the University of Brighton’s editorial photography course, it was the Northern Soul revival — music-minded partiers who escaped the acid house frenzy via dub, soul and rare groove.

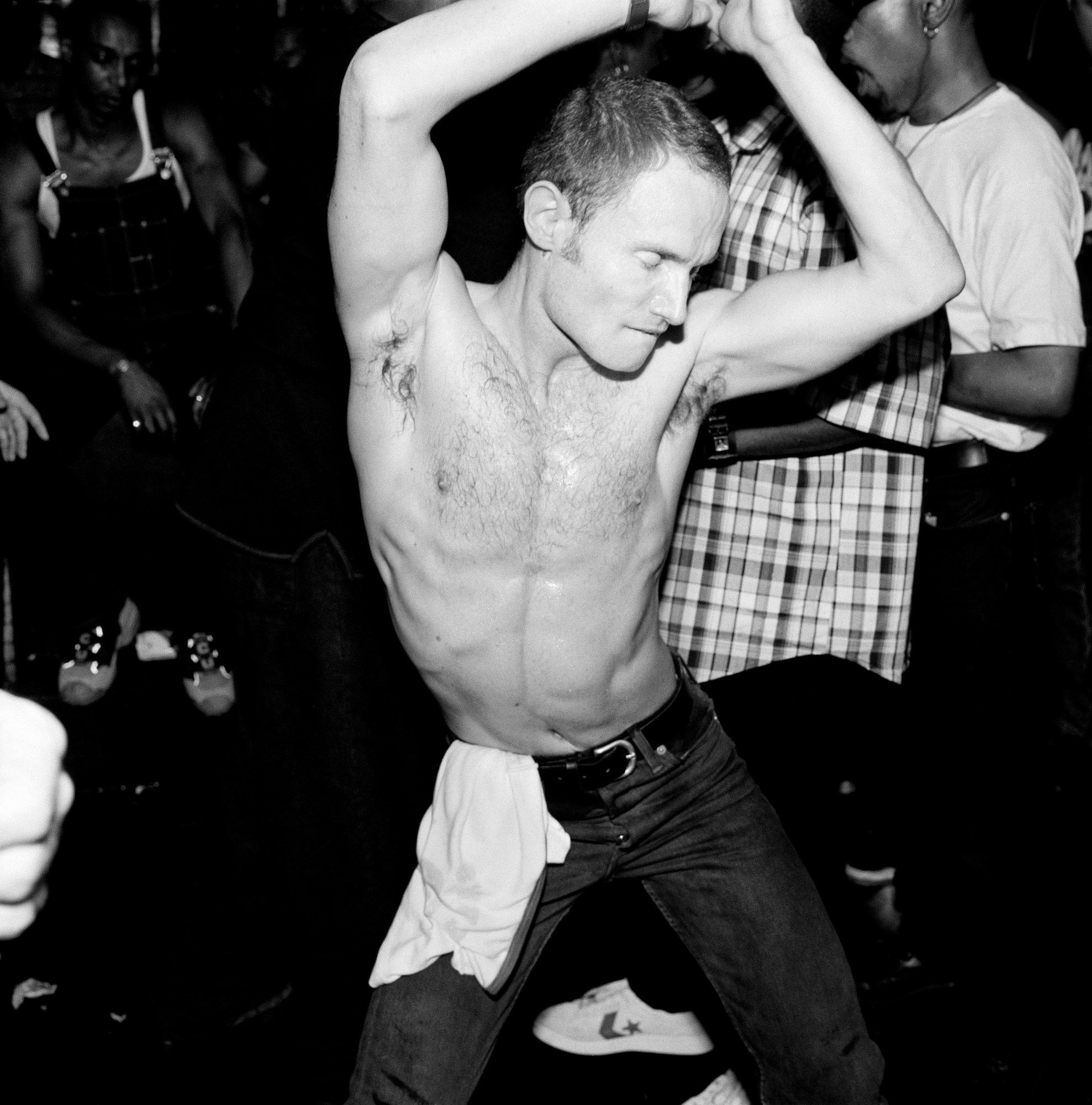

Sleazenation, a “post-drug culture” magazine (according to editor Steve Beale in 1999), at the time printed photographs by Wolfgang Tillmans, Jurgen Teller, Elaine Constantine and David Sims. Steve Lazarides, the photography director, asked Ewen to replicate his Northern Soul imagery across other subcultures, “which was contrary to the idea of contemporary club photography,” Ewen explains. His photographs were unchoreographed, visceral and raw: fly-on-the-sticky-wall rather than tripod behind the booth, a wry teaser to the club listings they accompanied at the back of the magazine. “I liked its Britishness,” Ewen remembers of Sleazenation. “That subversive, irreverent attitude to design. It was cheeky.”

While You Were Sleeping offers a snapshot of the next two years on the road — a travelogue of wide eyes, gyrating bodies, and dancefloors of scratched wood, muddied tile, and rancid carpet. Although London is the focus, the regions are well represented. Heavy metal fans at Nottingham’s Rock City (“I found them funny, but in a celebratory rather than mocking way,”); ecstasy-fuelled grins at Brighton’s Zapp Club and naked bodies at Wild Fruit, the city’s legendary queer party; normcore dancers catching their breath at NY Sushi, a drum and bass night in Sheffield.

Ewen was sparing with his film, allowing him to photograph two or three parties each night. Venues often held multiple events simultaneously, so moving between floors became a portal to wildly opposing youth cultures. At the Mayfair in his native Newcastle, downstairs played “crab dub” while goths and metalheads let loose upstairs.

The London images tell a story of rapid development as the East End became the city’s creative hub. This was the Jonny Woo heyday, where a crowd of “painfully hip people were playing ironic heavy metal records” at nights like Sonic Mook Experiment at 333 Old Street. Trance raves and Queer Nation at Sub Station South carried on strong in Brixton, while messiness reigned at unpretentious piss-ups from Clapham to Camden. One image shows DJ Spoony playing at Twice as Nice, the Sunday speed garage party at The End. Around the same time, Ewen would begin working with Mike Skinner from The Streets, who introduced him to a set of young artists from Bow taking UKG and making it ‘Grimey.’

How to understand this history in an authentic, untainted way? Photography can often be hijacked in service of nostalgia, convenient narratives it never intended to propagate. Compiling images in a photobook can contribute to this. Important details are omitted. Individuals become archetypes. Connections are drawn when in reality there were none. While You Were Sleeping centres on a very specific element of British youth culture — going out. It was later, in an extended project for The Face, that Ewen addressed British youth in its wider totality (these images would feature in the 2001 Barbican Centre show, Jam: Tokyo – London, and go on to comprise Ewen’s 2017 book Young Love).

While You Were Sleeping depicts a time when “the youth explosion — youth identity — was still being played out on the dancefloors of the UK,” Ewen says. Grime, on which his later works focussed, was “more about a kind of lived experience than the dancefloor.” Sleazenation celebrated stylistic heterogeneity: that in the UK, die-hard genre kids could dance alongside oblivious students. Grime’s early innovators had been denied a club culture of their own, hence a more coherent, community-rooted movement now hailed as intensely political.

“As soon as something becomes a bit more sussed and a bit more obvious, it naturally becomes more mainstream and more pop,” Ewen says. “That meant, for me, it became less interesting.” His logic cuts through any rose-tinted vision of the period as a cultural utopia. In reality, there were a lot of outright bad parties. Sleazenation’s listings pages became infamous — “slanderous and pretty brutal,” he admits — but they needed to be, because some of the clubs and parties deserved it. He remembers despairing as football hooligans (some of them his friends) started turning up at acid house nights in the early 1990s, pushing him further into the Northern Soul scene. If enough people you thought were uncool turned up to your party, you upped sticks and found a new one. Even the genre and sartorial tribalism which organised urban nightlife — and which runs so unmistakably through the book — at times approached something of a ridiculous spectacle, such was the stringency of its codes.

Could these photographs be made today? Social, urban and political conditions are different, but technological development is the main distinguishing factor. “No one had a camera in their pocket back then,” Ewen says. “We now have a perceived idea of what a club night should be, because there’s so much historical access to imagery and film.” Serendipity and surprise are perhaps in shorter supply. Youth culture and nightlife are now more bureaucratised and marketised, as are the cogs of cultural production itself (Ewen got the gig at Sleazenation by walking straight into the office and bumping into the editor; Sheryl Garratt, editor of The Face between 1998-95, recalls the days of “knowing what club people went to and going down to ask them if they wanted to be on the cover”). But people today still have that essential desire for escapism through partying. That Ewen’s generation no longer has access to it is more a sign of its evolution than its dwindling. (He agrees).

These images are a series of irreplicable, extraordinary, but flawed moments. In any case, rescuing them from posterity’s cultural airbrushing is crucial. A certain ineffability surrounds them, even as Ewen attempts to define what he was searching for all these years later. “What I wanted was the manifestation of something, something that was happening,” he writes in the book. “You can’t really replicate that excitement. It’s those places where it’s just kicking off, you know?” Spoken like a true twenty-something describing a big night out to friends. That sense of togetherness, of witnessing something worth witnessing, cuts across sound, image, and time.

Ewen Spencer’s ‘While You Were Sleeping 1998-2000’ is published by Damiani www.damianieditore.com at £40.

Credits

All images courtesy of Damiani and Ewen Spencer