Over the past 200 years, New York’s Lower East Side (LES) has been the epicentre of immigrant culture. As new arrivals crossed the ocean in search of the American Dream, many found shelter among their own in relatively homogenous ethnic enclaves that offered them a sense of familiarity in a foreign land. Living in slum conditions, many became radicalised, making the neighbourhood a hotbed left-wing politics.

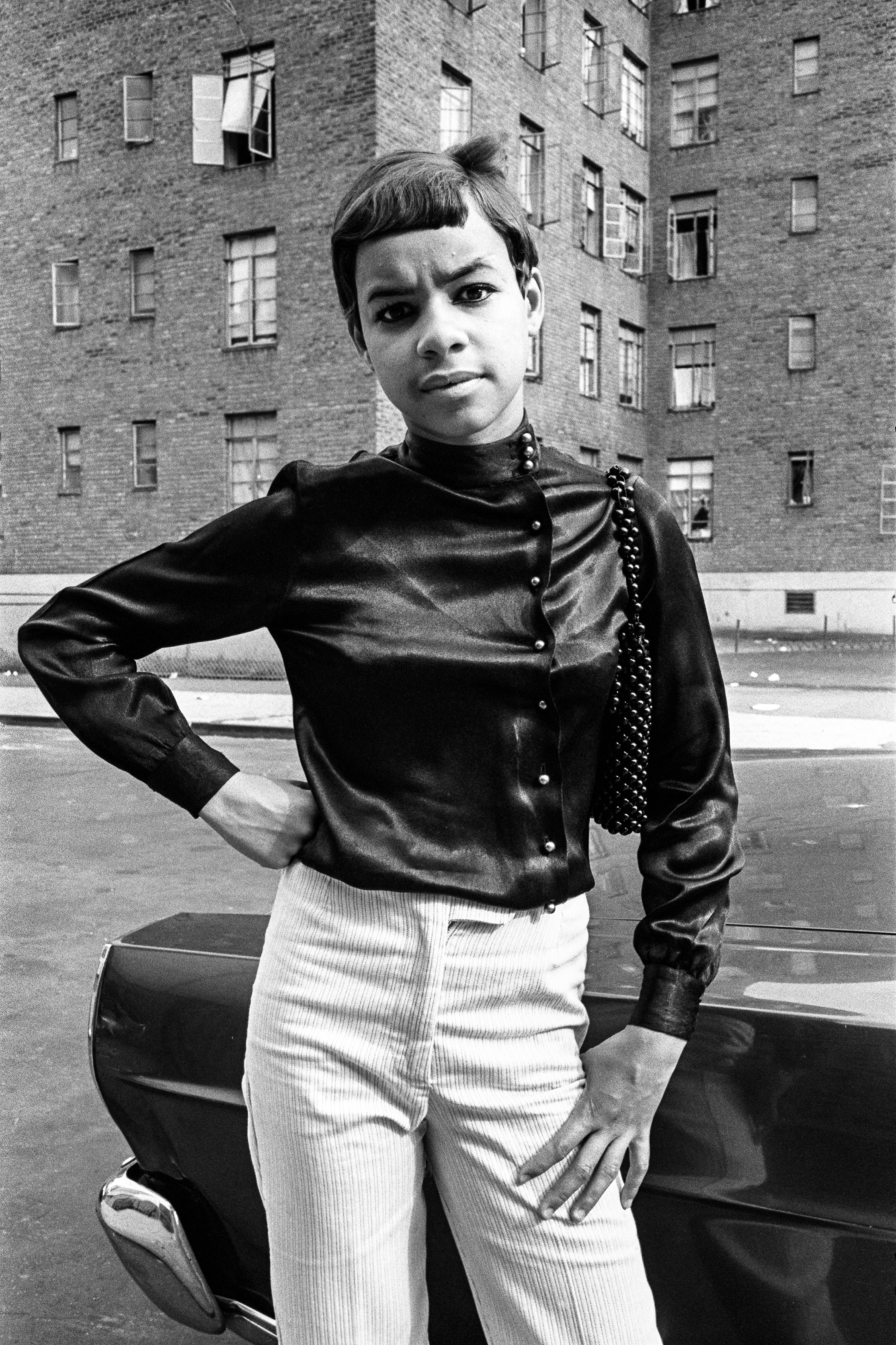

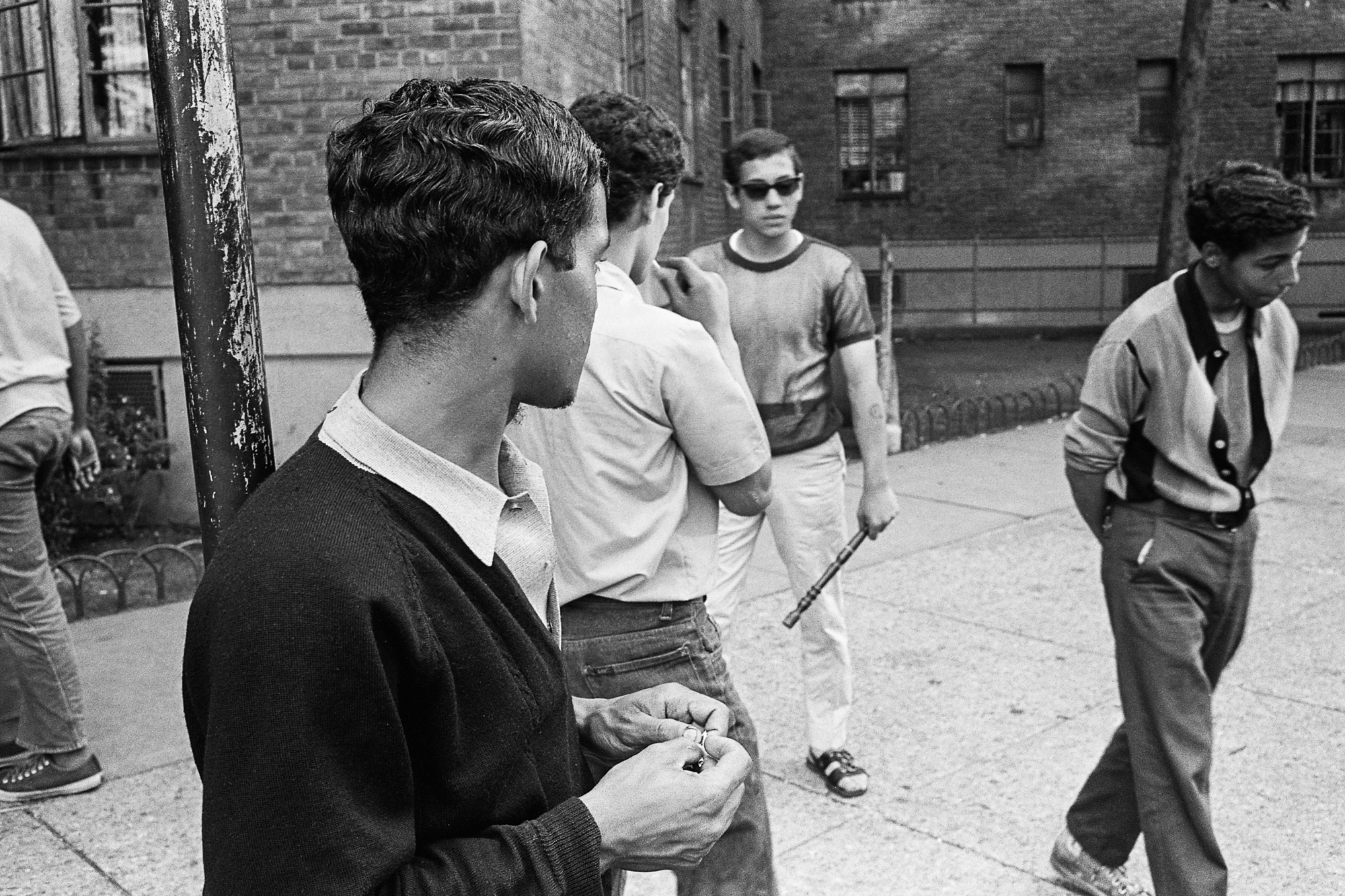

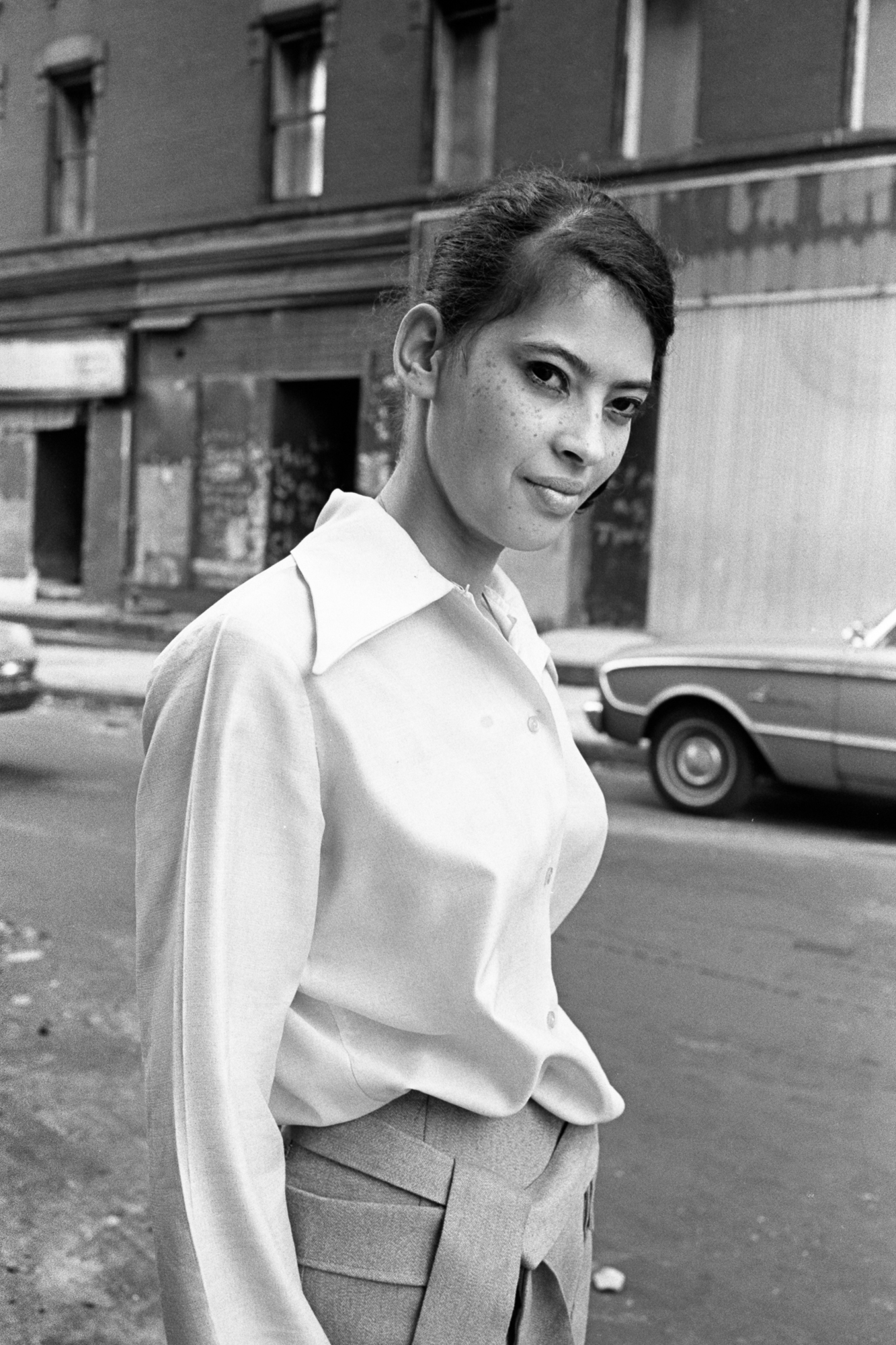

After World War II, the LES became New York’s first fully racially-integrated neighbourhood, as Black Americans headed north during the Great Migration to escape segregation, and Puerto Ricans moved en masse following the US radically reshaping the economy of the colonised island. By the 1960s, the people of the LES were plagued by poverty, crime, and drugs — but the community was also an oasis for bohemian culture, drawing artists, musicians, and writers into the mix.

In 1963, native New Yorker Nick Lawrence, then 22, and a friend from college, hopped in a car and drove around Manhattan to find their first apartment. “Somehow we ended up on Clinton and Stanton Streets, which we knew nothing about,” he recalls. “There was a sign in the window of luncheonette that said, ‘Apartment for Rent’ and that was it. It was a two-bedroom for $63 a month. My father was absolutely outraged. He said it shouldn’t cost more than $16 a month.”

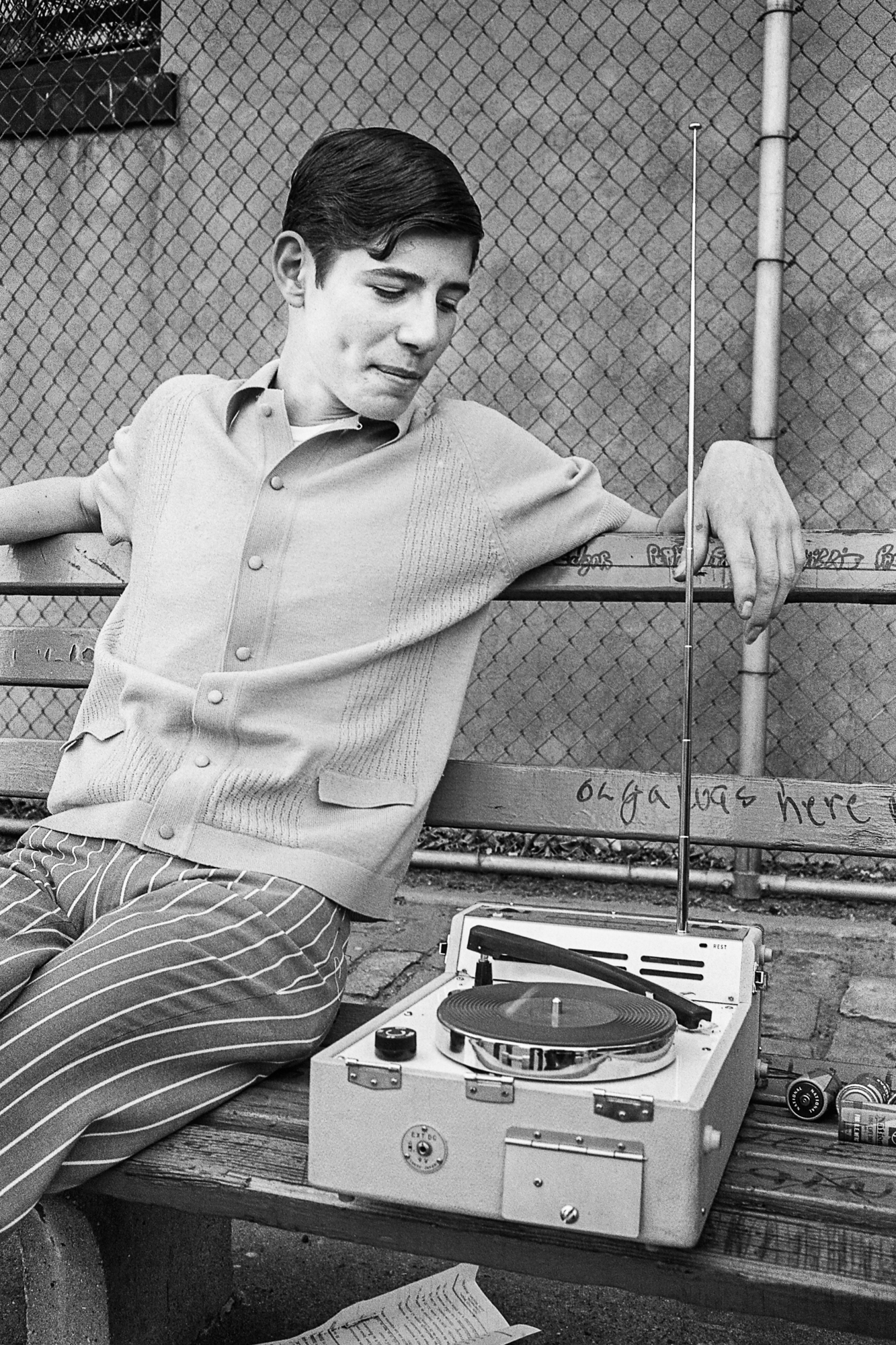

By this time, the neighbourhood was primarily Black and Puerto Rican, with a smaller community of Jewish people left over from an earlier era. “Our apartment was on the second floor, over the luncheonette. Across the street was a teeny little record store blasting salsa music all day long. The second or third day we were there, we were looking out the window and saw some guys coming down from the building across the way with a television that they were obviously stealing, and they waved to us!”

Hailing from Manhattan’s posh Upper East Side, the LES was a culture shock — but one Nick warmly welcomed. “I never really fit uptown, nor [did] my parents. They moved there so my sister and I could go to [good] schools but growing up, I wasn’t part of a community. In the LES, a lot of life took place on the street. There were older people hanging out, sitting on doorsteps and boxes talking while kids played in the street.”

In 1964, Nick joined the Fayette County Project and went to the Tennessee as part of a Civil Rights voter registration program to promote free and fair elections. He brought his camera on the journey — a wise choice considering no one else did. After working there for nearly two months, Nick was invited to travel to Mississippi and photograph for a couple of weeks. The pictures were published, and he became serious about photography. After returning to New York, Nick took to the streets, trying to photograph the texture and scenes. “I was looking for something, but my pictures weren’t really catching on,” he remembers.

Later that year he began working as an art teacher at a local junior high school just below Delancey Street. Although he didn’t have a calling, teaching was the perfect solution to a couple of issues at hand. Although Nick had not yet determined his direction in life, and teaching positions provided an exemption from the draft, which would send more than 110,000 Americans to fight in Vietnam that year alone.

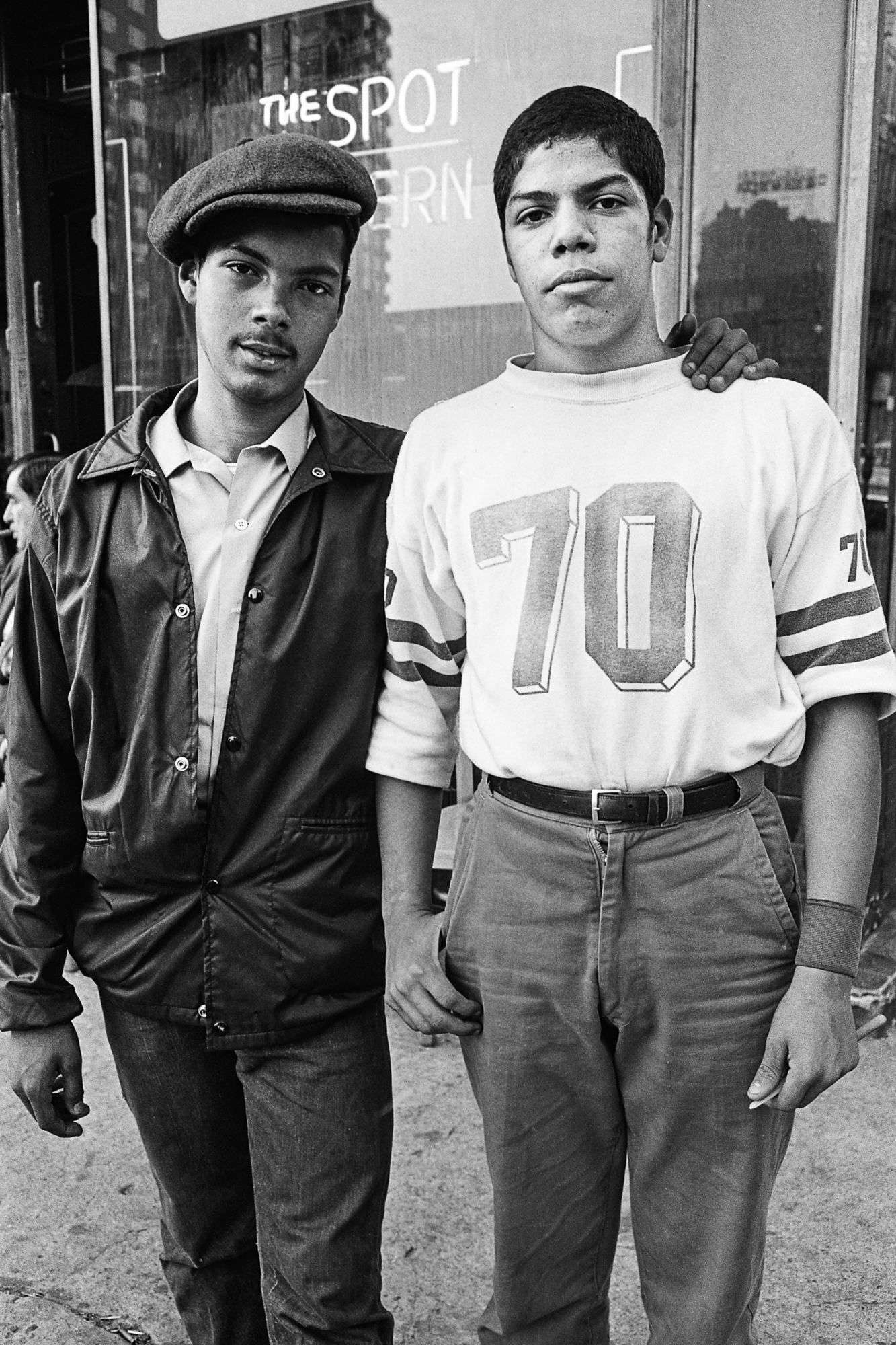

Nick quickly discovered he had a talent for teaching, but what he loved most was the relationship he shared with the students. The school assigned Nick to teach the “troublemakers” — a group of kids who had been sent to youth detention centres at some point. “They were all dumped into one class,” he says. “Discipline was enforced, and the main thing was to follow rules as opposed to educate them. I had my hands full but I really liked the kids and bonded with them.”

In the winter of 1966, Nick took a class with Lisette Model at the New School. She immediately took notice of the photos he was making of kids in the neighbourhood and encouraged him to keep going. Inspired, Nick brought his camera to school to photograph his students but found that setting far from ideal. Instead he decided to tag along with them at the after school program.

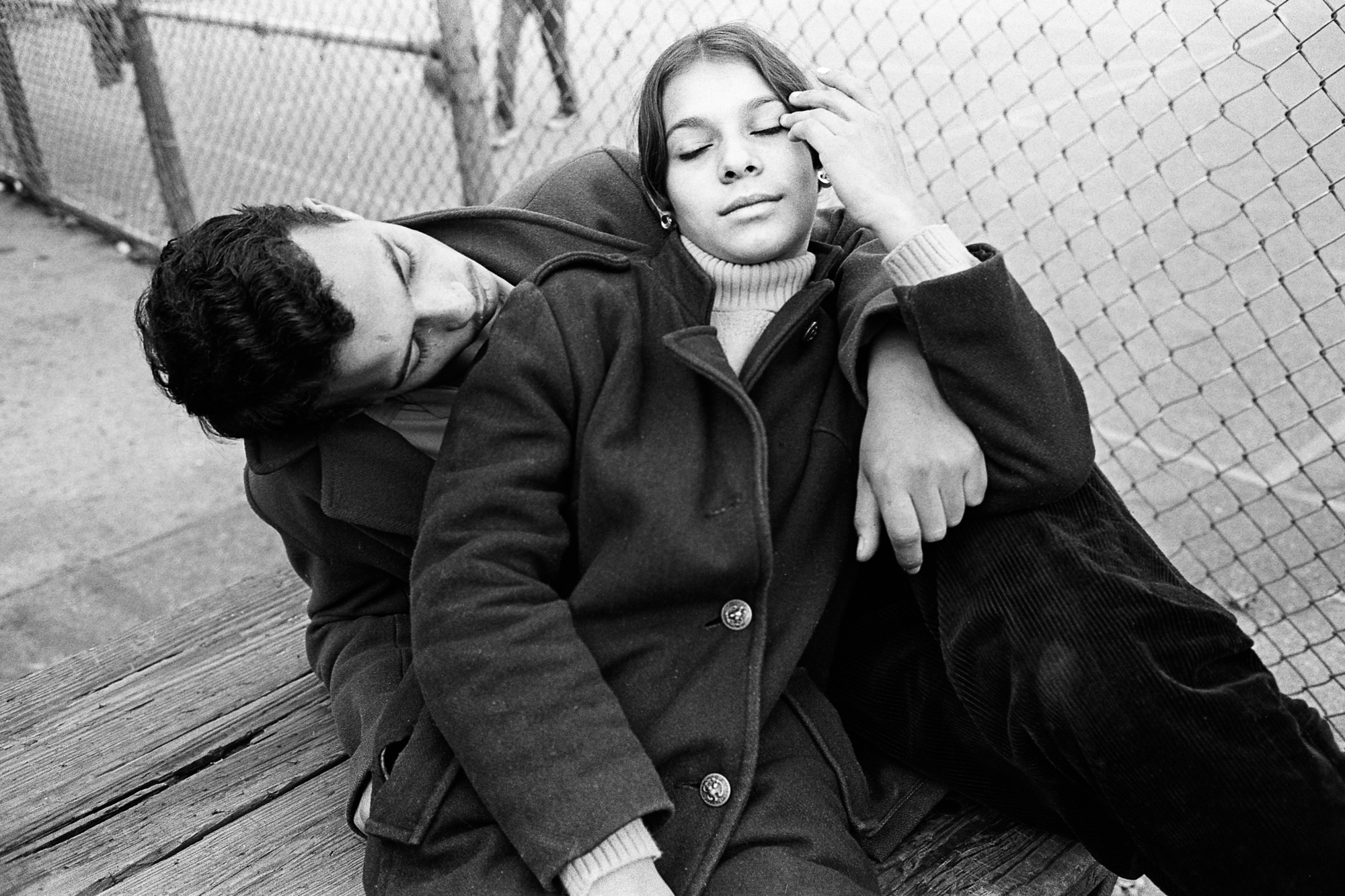

“I wasn’t part of the program but I could hang out with them,” he says. “I started taking pictures and became part of the fabric of the community. Everybody knew me and I knew everybody by sight. I was the only one taking pictures but I also blended in so that the kids weren’t really paying attention to me. I was looking for something deeper than the superficial pictures where people give you the cliché snapshot smile or start posing.”

For the next three years, Nick hung with the kids, amassing an extraordinary collection of work now on view in exhibition: Lower East Side Teenagers in the 1960s. “I have a lot of nostalgia for that period of time,” Nick says. “I was living a little bit of the street life I never had growing up. That was something special to me.”

Nick shares the story of one of the boys in the photographs named Carmelo. Their first encounter was a test: Carmelo raced down the school stairs and pushed Nick. “He was a tough guy,” Nick recalls. “I grabbed him and told him, ‘You can’t do that.’ He was screaming and I let him go. Then he left. I didn’t feel good about that confrontation, it wasn’t a typical thing that happened at the school.”

The next week, the school administration assigned Carmelo to Nick’s class, and they made peace. “We basically hit [it] off,” Nick says, “He used to keep order in the class and I couldn’t understand why. Then one day, I heard him telling someone, ‘Hey, watch out for Lawrence! He’s really tough.’ I realised he needed that as a way to justify respecting me because I was a total wimp.”

Although adolescence can be awkward, Nick found beauty and joy in these fleeting moments of life, just before innocence is lost. In 1969, heroin would flood the streets of New York. Sadly, the LES was hit hard as a result of Nixon’s “War on Drugs,” with many in the community falling victim to heroin addiction, including Carmelo. “A friend later told me he died of an overdose,” says Nick, who left the neighbourhood and moved to California in 1970.

“It’s a long time ago, but I miss the vitality and connection with community that comes from people pouring out into the street. My son, who is 29, moved to New York and lived with roommates on the Lower East Side just a couple of blocks from where I taught. Now it’s expensive apartments — a totally different experience. There’s something really positive about street culture and I hope it doesn’t disappear as a result of gentrification.”

‘Nick Lawrence: Lower East Side Teenagers in the 1960s’ is on view at Euqinom Gallery in San Francisco through March 5, 2022.

Credits

All images courtesy of artist and EUQINOM Gallery