Smack in the middle of Fire Island, a decadent strip of beach south of Long Island where New York’s queer partygoers from Andy Warhol to Halston came to let loose for summer, lies the remote hamlet of Cherry Grove. The Grove, as locals and regulars affectionately call the area, has an almost century-long history as a queer refuge that’s equal parts tranquil and hedonistic. It became a hotspot in the 1930s; by the 1950s, most of Cherry Grove’s population was made up of queer people, co-existing in harmony alongside straight families that had long-occupied the area.

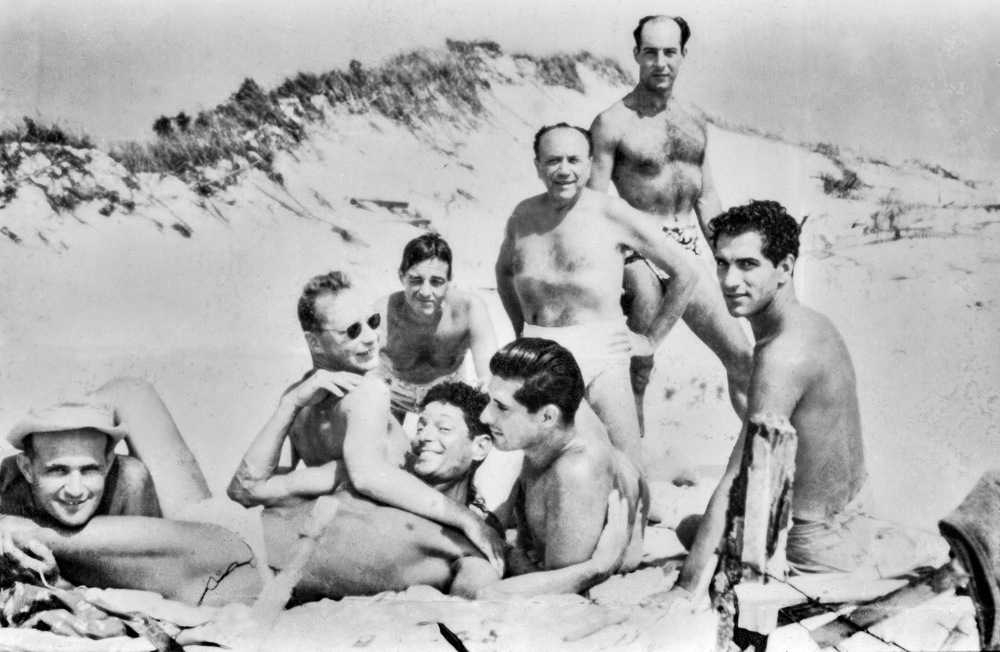

Before the AIDS crisis, before the Gay Liberation movement began to pick up speed and before the first brick was thrown at Stonewall, Cherry Grove became one of the few places in America where queer people could live their truth out in the open. Socializing without fear of judgement or persecution, taking lovers freely and reveling in their authentic selves, this sentiment of liberation persists on Fire Island to this very day.

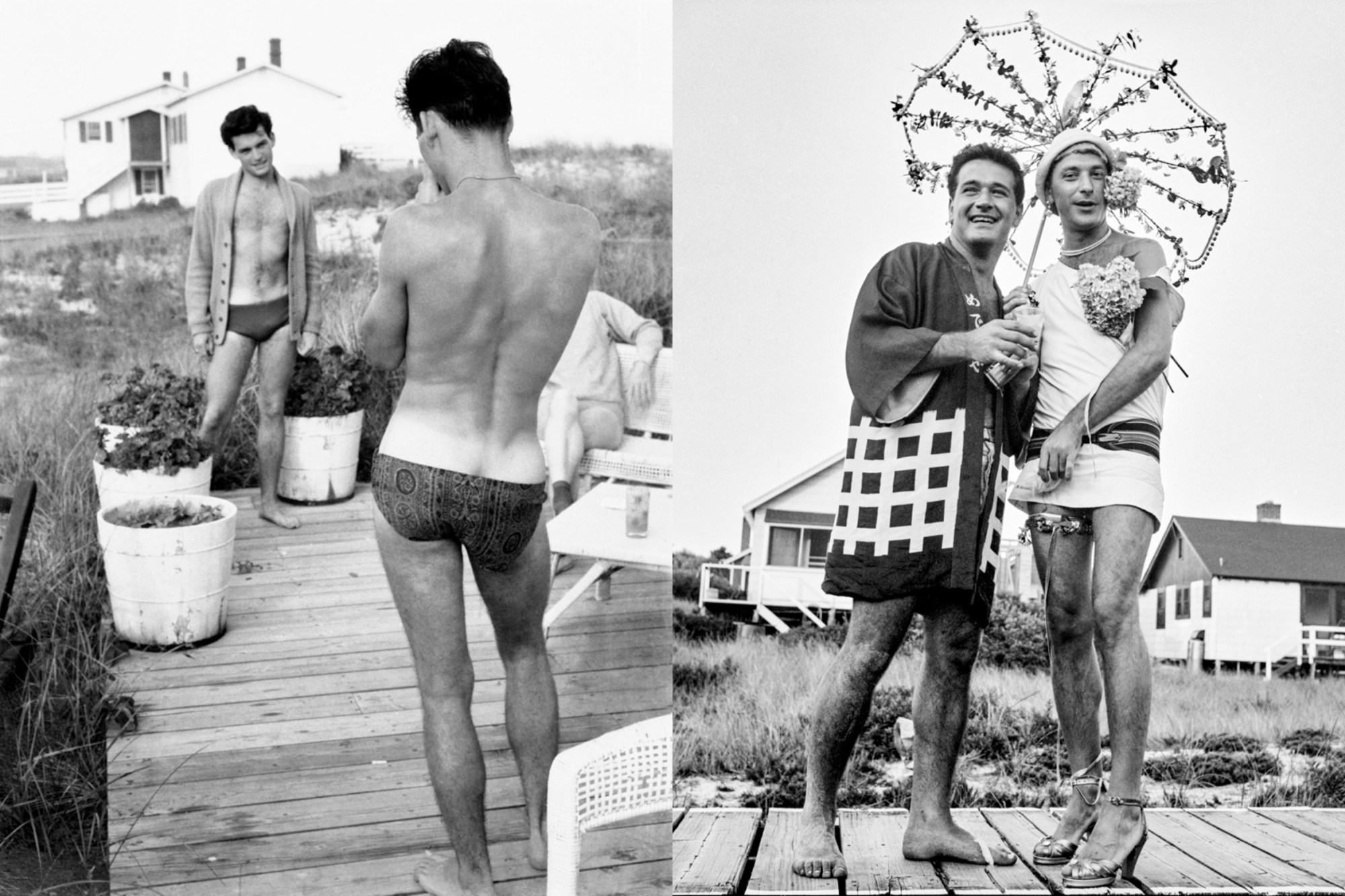

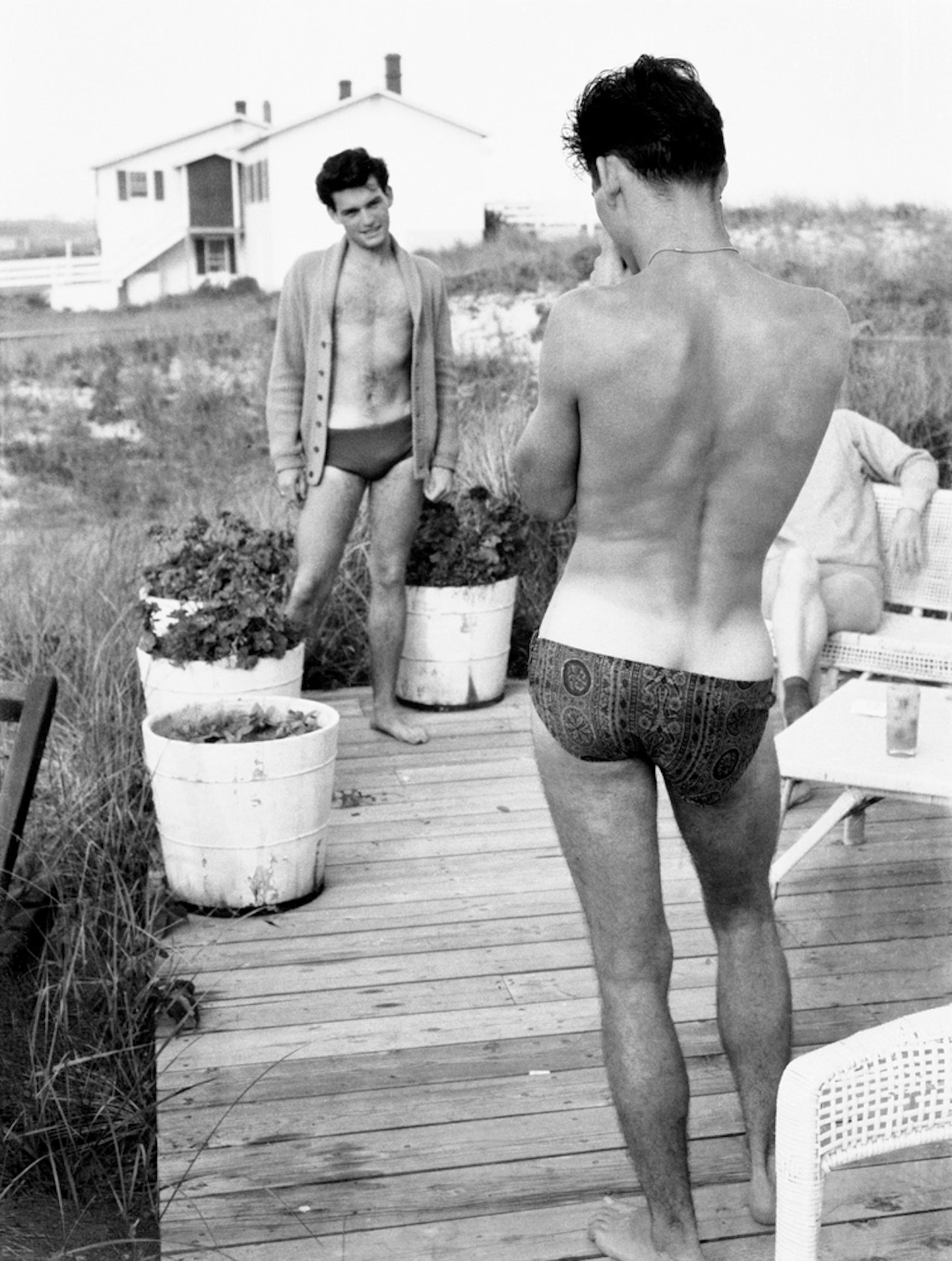

Safe/Haven, a free outdoor exhibition at the New York Historical Society, showcases this rich history through tender vintage photos of the era. Presented in conjunction with the Cherry Grove Archive Collection and co-curated by Brian Clark, Susan Kravitz and Parker Sargent, the intimate collection of home photographs documents markers of Cherry Grove’s golden age: decadent costume parties, lazy beach days and the extraordinarily brave people that dared to live truly under fire.

“During the 1950s it was extremely dangerous to be identified as a homosexual; a person could lose their employment, housing, family, or be arrested, physically assaulted, or even be psychiatrically hospitalized,” says Brian Clark on the exhibition. “To have a secluded safe place where one could joyfully explore one’s gay identity and openly experience a budding gay community must have been simply magical.”

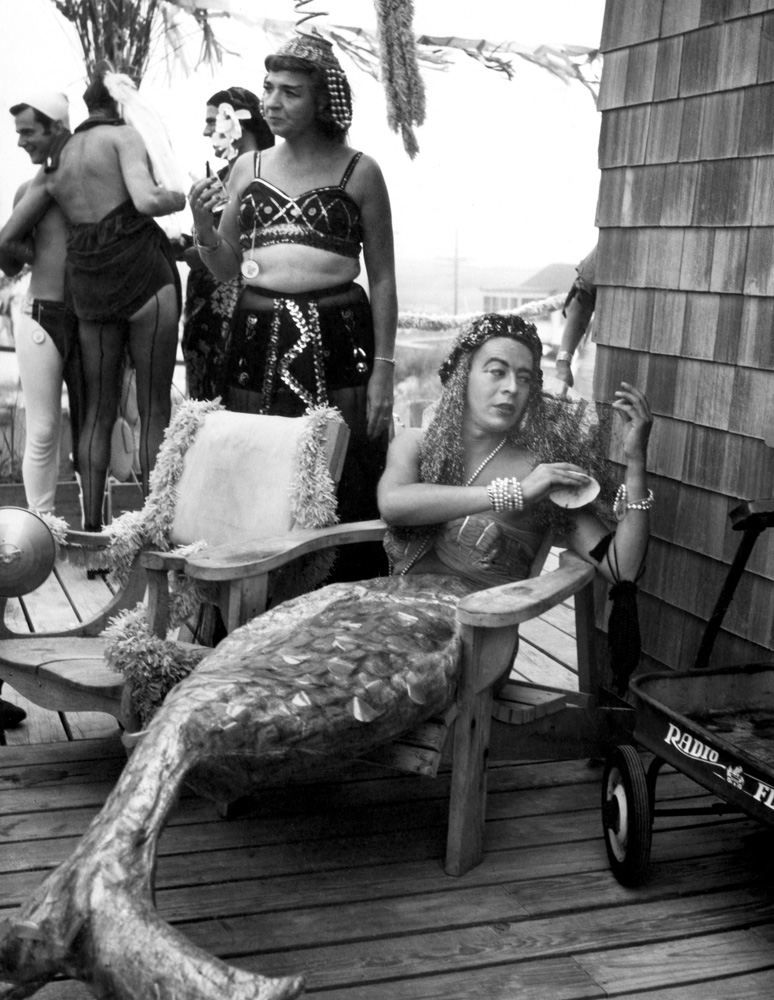

A sanctuary from the relentless oppression and persecution they faced, Cherry Grove was a safe place for its queer visitors to exist fearlessly. The community allowed creativity and personalities to flourish, from lavish costume parties thrown by party girls Mary J. Ronin and Kay Guinness — who famously told her husband that “when she came to the Grove, she arrived alone” — to performances from budding talents like Bob Levine, who quickly became a staple of productions in the Grove as his drag alter-ego Rose.

“Stonewall has always been a benchmark in gay rights, and for many of us, it’s where our idea of gay community begins,” says Parker Sargent. “These photos dispel the concept that all queer people were lonely and unhappy before the Gay Rights movement. In this very unique safe haven of Cherry Grove, gay men and women were discovering themselves and expressing their sexuality in ways they couldn’t even in the bars of New York City, likely taking those feelings of acceptance and freedom with them when they went back into the ‘real world,’ during the highly tumultuous McCarthy era.”

This break from reality had an element of bourgeois gatekeeping in place: most of the queer people that enjoyed the freedom of Cherry Grove in the 1950s and 1960s were white or wealthy people with the means to get there. The Grove enjoyed a cavalcade of high-profile (usually closeted) artists and writers basking on the sands including Anglo-American writers Christopher Isherwood and W.H. Auden, New York School poet and curator Frank O’Hara, The New Yorker’s Paris correspondent Janet Flanner (who wrote under the pen name Genêt after the legendary queer writer) and Italian cinema darling Gar Moore, whose Indigenous roots as a Cherokee Nation member are typically erased.

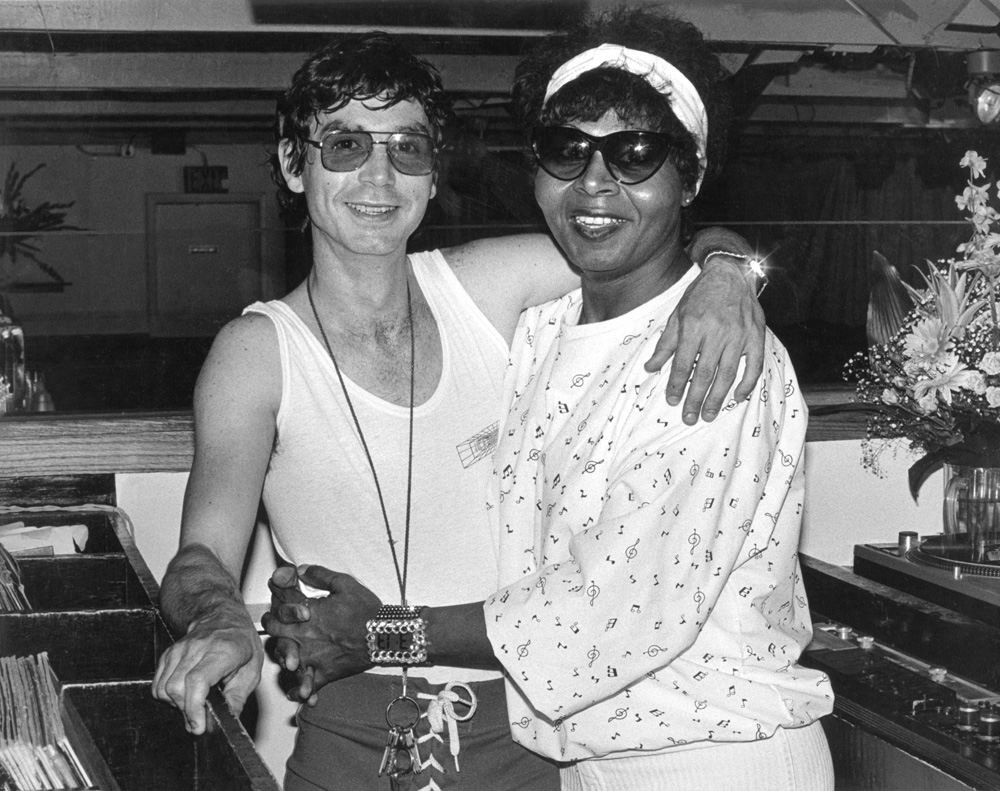

“Looking back at these images from the 1950s, we see all white faces, mostly men,” Parker says. “As a trans woman, I felt it was imperative to reflect that Cherry Grove is still a safe haven for so many of us. My trans siblings, people of color and anyone who feels disenfranchised for their self-expression of gender or sexuality, are still finding their way to this amazing strip of beach and experiencing the healing powers of nature and a community that accepts you.”

After the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, Black and Latinx people, as well as working-class lesbians and trans people, became a more potent presence in Cherry Grove. After the AIDS crisis devastated the area in the 1980s, it became a place of mutual aid networks as many cared for their ailing gay male friends. Eventually, the homes these men left behind would be bought largely by middle-class lesbians who ensured that the Grove would stay a queer created paradise that, now more than ever, is for all of us.

“Discrimination is a painful part of 1950s America, and while we cannot change history it is important to understand and learn from it,” Brian says. “We felt it was important to show that the Cherry Grove community had increasingly become a safe haven for a more inclusive community that welcomed a greater number of women, people of color and the trans community.”

Safe/Haven is open outdoors at the New York Historical Society through October 11. Reserve a timed-ticket here.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more photography.

Credits

Photography Cherry Grove Archives Collection