If you’ve ever spent more than five minutes on TikTok, chances are you’ve happened upon a teenager talking about #health. The hashtag accounts for over 20 billion views on the platform and its more ‘niche’ iterations — be it #OCD, #ADHD or the Tourette’s-positive “tic” Tok — are rabbit holes of candid journey-sharing content: some serious, some uplifting, some self-mocking. But scroll to the bottom of any such video, and you’ll quickly come across a comment that calls bullshit, and accuses its creator of being a fake.

Becca Braccialle was diagnosed with Tourette’s in October last year and has been using TikTok to raise awareness about the condition ever since. Her account — @tourettesbian — has 568.3k followers, and her videos have over 12.3 million views. But, almost instantly, Becca’s decision to document her experience made her a target for hate and accusation. “I get these comments a lot,” she explains in a recent video, “and I just thought I’d let you know… how proud I am for doing this. And I really hope you’re proud of yourself too for bullying disabled people online.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the global pandemic, health-related content looks to have taken off on TikTok over the past year. As Gen Z faced school closures, fractured social structures and increased levels of depression and anxiety (which more than doubled among UK teenagers during the pandemic), the app provided a sense of community and belonging to people like self-proclaimed mental health advocate Max Selwood. “TikTok is like a form of therapy. If I just speak about [my mental health] to as many people as possible, it feels less scary.”

In October last year, TikTok acknowledged the influx of new creators by introducing its network of “wellness warriors”. In April 2021, it launched its #WellnessHub — a space for users to connect and discover lifestyle and health tips. But as health-related content surges, and its most popular creators are quick to reach influencer status, an insidious trend is rising in tandem — those who appropriate illness for clout.

Faking illnesses is no new ‘phenomenon’ — some of those who do it have a recognised mental illness known as Munchausen’s syndrome, or ‘factitious disorder’. Those with this complex psychological disorder feign or deliberately induce symptoms of illness in themselves. There’s also Munchausen’s by proxy — which you might be familiar with if your lockdown binges included either Hulu’s The Act or Netflix’s The Politician. Both were inspired by the story of Gypsy Rose Blanchard, whose mother subjected her to a lifetime of abuse, lying about her cancer diagnosis, and forcing her to act as if she were physically and mentally disabled. Eventually, Gypsy Rose arranged for her boyfriend to murder her mother.

And since the advent of the world wide web, there’s also ‘Munchausen’s by internet’, a term coined by MD Marc Feldman in 2000. “I first became aware of it in 1997,” he says. “One of my student nurses told me about a monk who had been documenting his experience of terminal cancer in an online forum. His religious vow of poverty had meant he was unable to get treatment and he was suffering severe loneliness.” But his posts were incredibly lengthy, involved and continued well past the time Feldman would have expected him to pass away. “Eventually, after receiving several private emails, he — or I’m not even sure it was a ‘he’ — admitted the whole story was a hoax.”

Earlier this year, doctors from the UK’s Great Ormond Street Hospital said they were seeing a significant increase in tics in teenage girls – despite Tourette’s being much more common in boys.

Stories like this are not uncommon, and many are much more high-profile. In 2014, there was Belle Gibson — the apparent “cancer patient” who survived her battle with a brain tumour after cutting out gluten and dairy, and became a wellness warrior. ELLE called her “inspiring”, Penguin published her cookbook. She was then supposedly diagnosed with other cancers, before finally admitting it had all been a lie. Five years earlier, there’d been the April Rose hoax, which still stands out to Feldman because of its magnitude. “April Rose was the name this woman gave to her non-existent foetus,” he explains. “The [supposed] unborn child allegedly had a severe chromosomal defect that was invariably going to lead to death, either in the uterus or shortly after birth, but she chose to carry it to term.” April Rose became the poster child of the Pro Life campaign, an emblem for the anti-abortion, anti-choice community. “It became a big movement,” says Feldman. “She became a cause celeb and immense numbers of people were deceived.” Beccah Beushausen (previously known only as “B” or “April’s mom”) was exposed shortly after ‘giving birth’, when she posted a picture of the stillborn baby, which turned out to be an ultra-realistic doll.

Both Belle and Beccah typify the average “poser” in Feldman’s experience (“I struggled with what to call them. Patients? Perpetrators? Both seemed too judgmental.”). They were both women in their mid to late twenties. Feldman explains that most posers have suffered some form of childhood trauma, and have developed personality disorders as a result. They are not delusional — they are fully aware that they are lying. Nor are they deceitful for practical purposes — to claim disability benefits, for example. They start GoFundMe’s not for money, but “for attention, care, concern, tangible evidence of another person’s sympathy towards [them]. They have longer term, maladaptive ways of trying to get their needs met.”

And online, where popularity is visibly quantifiable via ‘likes’ and ‘shares’, getting needs met has never been easier. In an age of diminished attention spans, endless scrolls and fake news, deception requires little energy, and to some extent, we’re all guilty of it — if not entirely fabricating, then presenting more polished versions of ourselves and our lives. “Social media is seductive,” Feldman explains. “It appeals to people who are hungry for attention and sympathy.”

In Feldman’s experience, the most common stories of Munchausen’s by internet follow widely-known, well-documented narratives. “Cancer is always the number one offender, because everyone knows what cancer is,” he explains. “It doesn’t involve a long, manufactured description or explanation, and it instantly evokes an emotional response.”

But video-first platforms like TikTok are changing the way Munchausen’s syndrome manifests. As moving image eclipses static posts, posers are choosing dynamic disorders — and ones that can be easily exaggerated for comic effect. One apparently common culprit is Tourette’s, as well as the general impersonation of similar motor and vocal tics. Videos show mundane activities being interrupted by expletives, and often more extreme outbursts than those most common with Tourette’s, which may be less noticeable in a short video.

There’s also dissociative identity disorder (or #DID), which, despite being a relatively uncommon disorder, has over 700 million views. Previously known as multiple personality disorder, the psychological condition is often defined by the experience of two or more distinct personality states (‘alters’), showing up on TikTok in the form of (literally) characterful videos. There’s the “meet the system” trend (here, here, here and here) in which people introduce their different alters, and the “catching my switch on camera” trend, in which those claiming to have DID capture the experience of dissociating on camera. For a poser, DID offers the opportunity to adopt and act out different comedic personas.

The romanticisation of suffering on social media is nothing new. Before TikTok we had pro-ana “thinspiration” on Tumblr (which is slowly creeping into TikTok), and the glamorisation of self-harm. Instagram meme account @mytherapistsays has 6.4 million followers for its ‘relatable’ depression-heavy content. In 2013, The Atlantic wrote about the “online cultivation of beautiful sadness”. A 2017 study found that social media promoted psychological burdens as “desirable and necessary” — (even Billie Eilish has been called out for it.) The image of suffering is so prolific that mental health struggles have almost become a personality trait, and Feldman affirms that more “exotic” conditions play into this complex. “I would ask what is their agenda — if they have legitimate DID — for parading it online to strangers? Unless one is seeking to elicit attention and sympathy, or is seeking to be special in some way — like they’re deeper than most other people, because they supposedly have DID, or some other relatively esoteric ailment.”

Feldman explains that because DID is a subjective diagnosis it makes it hard to irrefutably contradict someone who claims to have it. “It’s one of those faddish diagnoses that has actually fallen out of favour a bit recently,” he explains. “It always struck me as being suspect. But I’m a little surprised to hear that people are doing that frequently. Most people can’t willfully, at least early in therapy, call on one personality or another to make for a great video.”

When it comes to Tourette’s, the water gets even muddier. Earlier this year, doctors from the UK’s Great Ormond Street Hospital said they were seeing a significant increase in tics in teenage girls — despite Tourette’s being much more common in boys. While this is largely suspected to be an anxiety response to the pandemic, there’s also speculation about TikTok’s direct role in the uptake of tics. The normalisation of Tourette’s on TikTok has not only allowed people to recognise its more subtle symptoms in themselves, but could apparently also be causing its surgence in the form of ‘suggestibility’, or thinking into existence (whereby people essentially copy and absorb behaviours they’ve had exposure to). Researchers have likened the phenomenon to “dancing mania”, which saw a mass outbreak of spontaneous dancing in the Middle Ages.

But while it’s incredibly difficult to definitively ‘diagnose’ a fake, many users who create health-related content are becoming subjects of aspersion, facing backlash and trolling in both their comment section and elsewhere online.

At some point in our lives, we’ve all embellished the truth, told tales, or flat-out lied for one reason or another. I once claimed my dad was Charlie from Busted to make friends with a popular girl at school. With apps like TikTok, we’re seeing those lies becoming more prolific, exaggerated and consequential – precisely because they are so public.

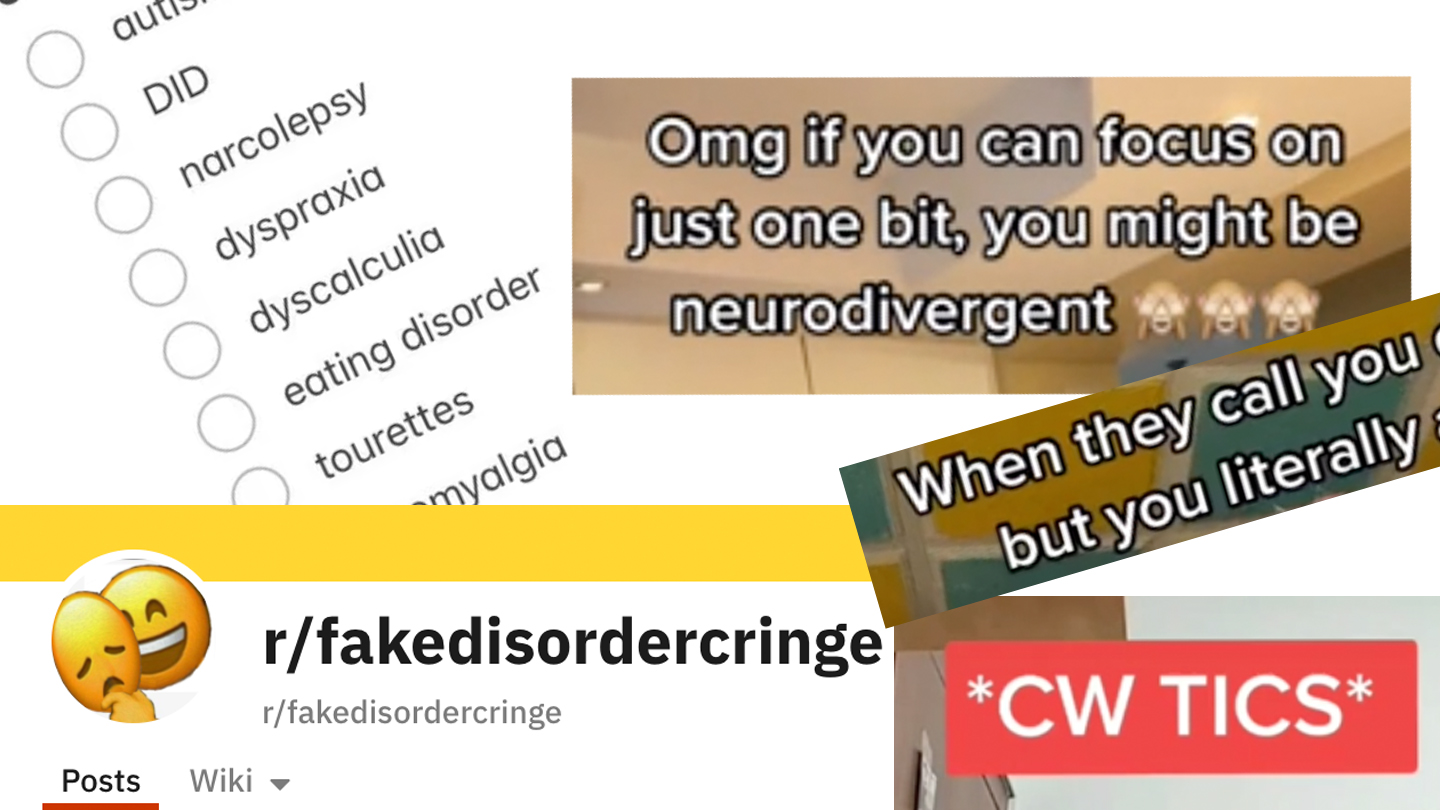

The subreddit r/fakedisordercringe has been dedicated to outing posers online since before TikTok, but it’s now overwhelmingly dominated by content from the app. There’s an entire subreddit dedicated to exposing the now-deleted (and thus supposedly now-exposed) account @ticsandroses, who was being lambasted online by many people — both with and without experience of diagnosed Tourette’s — for “obviously faking tourettes for attention”.

This policing of illnesses online often verges on bullying, and can have serious ramifications for both posers and people with real-life conditions. It creates a “boy who cried wolf” culture around health on social media, which subjects actual sufferers to skepticism and condemnation. “It’s really damaging,” says Becca, who has also had videos of herself posted on the Reddit forum, eventually resorting to uploading her diagnosis online in order to put an end to the accusation. She’s still frequently tagged in comments by users asking her to clarify whether someone else’s tics are real or fake. “I’m not a medical professional,” she says. “It’s not my place to decide.”

Feldman calls actual sufferers “the real casualties of deception — because they are there legitimately seeking help. When the skepticism ends up undermining their efforts to get it, that’s just deeply unfortunate.”

And it easily becomes dangerous for posers, too. Doxxing, in which an individual’s private or identifying information is revealed online, though technically banned on most sites, is becoming more frequent. “I certainly have a problem with that,” says Feldman. “We all make mistakes. I don’t think visiting someone’s home or making them a public spectacle beyond what they’ve already done to themselves is useful.”

Kids fib. At some point in our lives, we’ve all embellished the truth, told tales or flat-out lied for one reason or another. I once claimed my dad was Charlie from Busted to make friends with a popular girl at school (I didn’t realise he was only nine years my senior). My friend, an only-child, pretended to have seven siblings to impress a boy on MSN (he came from a big family.) With apps like TikTok, we’re seeing those lies becoming more prolific, exaggerated and consequential — precisely because they are so public. “Social media isn’t easy,” Max affirms. “Being in a world where your life is on camera and fully accessible to pretty much everyone — it’s hard. Kids are kids — and kids are going to say shit that they don’t mean.”

Unlike most previous cases of Munchausen’s by internet, many of these supposed TikTok posers are literal minors — children who may be living with personality disorders and/or trying to compensate for a deficit in care and attention. Berating them on the internet does little to help solve the issue at hand. “Cancel culture is a double-edged sword,” says Max. “There are of course times when people need to be corrected, because being corrected is essentially just being more accepting and inclusive, but I think people should be allowed some sort of leeway.”

Feldman describes individuals with Munchausen’s as both “troubling” and “troubled”, and that kind of hits the nail on the head. Accepting that posers also suffer, but from a different kind of condition to the ones they adopt, does not diminish the harm caused or the ramifications of their deceit — it merely helps us understand the psychology so they may be treated. Feldman stresses that the most important part of treating a poser is finding a therapist who is able to reserve judgement, which can be challenging when hearing about the magnitude of the number of people who have been hurt and deceived.

“It’s important to understand that many people with personality disorders have been traumatised in childhood — that can range from emotional neglect to sexual abuse. They may have PTSD, and depression is common. So [Munchausen’s] becomes a contorted way of trying to get the support for otherwise unrelieved depression.”

In fact, Feldman suggests that a diagnosis like depression, bipolar or an anxiety disorder in a poser actually improves the prognosis. “That may seem counterintuitive, but those are generally readily-treated ailments. And once we’ve effectively treated them, the impulse to engage in deception to get needs met really fades.”