What a year it’s been for fashion! Across every level of the industry, seismic change has been afoot, but perhaps more than any other alleyway of fashion, it is the students around the world who have faced the most adversity due to the pandemic. Many of them have had their courses paused and re-structured, workshops closed and vital equipment and resources out of reach, communities in isolation, technical training reduced to digital presentations. But they move. Last night, Central Saint Martins’ BA Class of 2021 showed up and showed out.

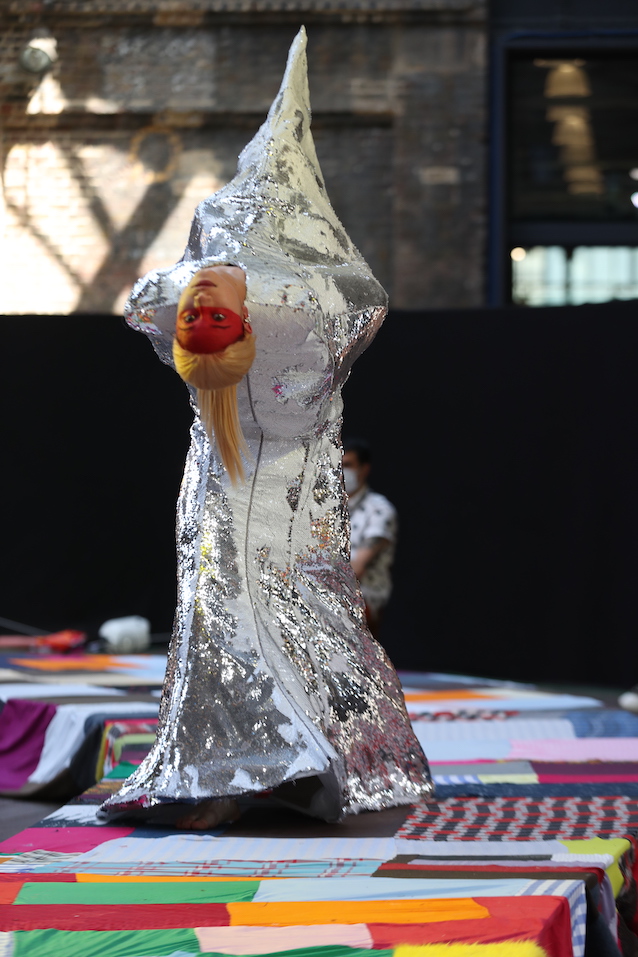

In what must be the first proper fashion show in London for over a year, the socially-distanced, outdoor extravaganza saw each of the 100-or-so graduates of the BA Fashion course model their own designs on a catwalk crafted from upcycled fabrics, surrounded by huge cardboard sewing machines and… giant inflatable rubber duck containing a model writhing around in a paddling pool. Yes, that’s right, the fashion show is BACK. Haven’t you missed it?

But beyond the weird and wonderful, there were also important messages in the work itself, showing that fashion can be a conduit for cultural conversations. Of course, given that these are the young fashion superstars of tomorrow, it goes without saying that the work on display grappled with the most pressing issues facing fashion today. Most of the designers can tell you the myriad ways they’ve sought out solutions to fashion’s endemic waste and excess, and many of the collections took a hand-crafted approach to textiles. Themes of decolonialism, gender identity, body distortion and innovative artisanal techniques also rose to the fore, and it was truly diverse as a result.

Here, we speak with ten of CSM’s Class of 2021 about their collections, the task of creating them during lockdown and what it’s like to graduate at the weirdest time in history.

Ben Redouane Bennai

How would you introduce your graduate collection?

It’s an attempt to explore the intrinsic appetite for stories and escape that we humans seem to share. Throughout my life, I’ve found myself drawn to using humour as a coping mechanism and this collection has been a way to disarm harsh realities in order to make work that is both melancholic and credible.

What were the most unexpected challenges and positive outcomes you experienced while creating your collection?

Making this collection in my childhood home was cathartic and hellish at once. I found comfort in burying my head back into the books I used to insist on being read to me before bed, but it was a challenge not being able to work with my classmates. I love them a lot and I really missed having nobody to annoy all day. Making the majority of this collection in a state of isolation felt dystopian and I felt as though I was losing my marbles slightly, but I didn’t mind at all. It was actually quite chic.

You’re graduating at a time when conversations around race, gender, sexuality, class and wider issues of identity have never been more prominent in fashion. How do you position your work with respect to these conversations?

My work is about the human psyche and our collective experiences. The world has faced so much turmoil lately I think we need a form of escapism more than anything. There is no political trojan horse here — I want the work to represent a neutral experience that isn’t culturally derivative. Inclusion is the main incentive, and I don’t want any one person to like my work more than another because of where they’re from or their gender. I am from a very working-class background, but I’ve never attempted to fetishise this. I think the things that anybody can relate to will always be most powerful.

Bysanz Baizhen Zhou

How would you introduce your graduate collection?

I named this collection ‘Facima’, after a hunter who represents the post-human and the cyborg body. This collection also serves as a metaphor for the introduction of regeneration potential into the human body through a combination of knitted techniques and materials. It is also a representation of a cyborg ‘sex symbol’ figure — a hybrid of object, animal and human. A machine without boundaries.

You’re graduating at a time when conversations around race, gender, sexuality, class and wider issues of identity have never been more prominent in fashion. How do you position your work with respect to these conversations?

I think my work communicates a utopian ideal, in that when technology brings us closer to the concept of cyborgs — when body, clothes, fabrics, wearables all integrate with the human body — it allows us to break the boundaries and conflicts of identity. But it’s not only in fashion that the issue of identity is being discussed so intensely today, and that we are all becoming more concerned with self-identity. I hope that by creating the image of ‘Facima’, we can bring more attention to the development of the relationships between people and technology, and how that could enhance the further development of how we understand identity.

How have the past 15 months shaped your understanding of fashion’s purpose?

Because of COVID, we’ve seen a lot of brands present their work in many different ways. It makes me feel that even if you can’t see a showcase in person, you can still present the clothes very well. Garments are only one part of the design process — creating a visual identity, an image, a short film and the design itself is the only way to fully express your collection; to tell a story that makes the audience want to be a part of it.

Chie Kaya

How would you introduce your graduate collection?

Growing up in Japan, I was always inspired by the concept of timeless Japanese beauty. Since I was a kid, my grandmother used to tell me that women preserve beauty naturally and age gracefully. The frustration of admitting that aging is human nature, while also believing in the idea of aged beauty, lead me to explore this unspoken ‘tension’ by using fabric manipulations to express my emotions towards the contemporary obsessions with youthful attraction and status.

What were the most unexpected challenges and positive outcomes you experienced while creating your collection?

This collection could be described as a realisation of myself. It was very challenging to try to evoke a very specific thing that departed from an abstract feeling. I’ve always been a detail seeker, focusing on very well-made finishings and tailoring during my first and second years. Experimenting with materials that were unfamiliar to me was very tough, to the point that there were times I really doubted if it would actually work out! It was a big push to keep challenging myself, but that’s how I found who I am today and why I make fashion.

How have the past 15 months shaped your understanding of fashion’s purpose?

After this collection, I realised that I want to make pieces that are timeless, which won’t be replaced by changes in trends. Fashion should have a purpose, and mine is to deliver pieces that are very well-made, refined, and high-quality; pieces that you could wear for 10 years, just like how my mother still wears a jacket she purchased when I was born — and it’s still in such good shape! And, as a woman, I think it is crucial to think about my own experience — how clothes make me feel; how the drapes and the cuts of a silhouette, for example, can defend against fear, vulnerability and insecurity. I want the women I am designing for to feel confident.

Claudia Gusella

How would you introduce your graduate collection?

A useless exercise in theatrics (in the best possible way) without any side effect on the planet! I wanted to make the escapist collection of my dreams, finding refuge in history and hiding secrets in symbols. All of this, while having the least environmental impact I could do.

You’re graduating at a time when conversations around race, gender, sexuality, class and wider issues of identity have never been more prominent in fashion. How do you position your work with respect to these conversations?

I come from a very working-class environment in an industrial region of North-Eastern Italy. My first job in London was as a kitchen porter, then I was an apprentice in an upholstery studio for a couple of years. Eventually, CSM happened, and being a full-time student during the pandemic meant ending up on universal credit. My collection is an ode to resourcefulness. My ecological choices were also moved by the intention to keep the costs low. It’s still an awkward conversation in the fashion industry, class and money. Working-class people are simultaneously fetishised and excluded through entrenched behaviours like unpaid internships and the difficulties of accessing student maintenance loans if you weren’t born in the UK. My insignificant way to address this issue in my collections is to make posh, powerful, wealthy people desire a dress made of beer cans and food waste.

How have the past 15 months shaped your understanding of fashion’s purpose?

The pandemic made me question all the life choices I had made up until then. Who needs fashion in front of illness? In front of death? It turns out that I did — a lot. My little lockdown projects made with upcycled materials from previous work kept my hands and mind busy. It made me confident that, no matter what, I will always find a way to express myself creatively. That said, I am still asking myself if these feelings are enough to justify the horrors we allow in this industry — the tremendous toll on the environment, a toxic ‘you have to sacrifice everything else if you want to make it’ attitude, the burnouts, the free labour, ageism, ableism…

Dylan Mekhi

How would you introduce your graduate collection?

An exploration of the self and individualism through community, an examining of culture, heritage, and personal history; of characters whose paths crossed over mine, lending to the development of my experiences and perspective. Family members, friends, lovers, neighbours, uncles who aren’t uncles, cousins who aren’t cousins. Community, conversations, memories, dreams: does the self exist without these things, without the collective? The collection also explores Creole and Jamaican aesthetics, informed by Caribbean philosophy and the central notion of the literary movement créolité — an active process of forming identity that looks forward to a post-essentialist future.

What were the most unexpected challenges and positive outcomes you experienced while creating your collection?

My most unexpected challenges and positives kind of went hand in hand. Due to the global pandemic and the fact that I am an international student, the travel bans did not allow me to return to London for my final year. I made my entire graduate collection out of my small New York apartment. The lack of studio space, lack of access to industry-level machines, and working in comparative isolation was a huge challenge throughout. But at the same time, the lack of resources forced me to push myself further than I would’ve in terms of what I was making and the execution of it. And the extreme isolation from all of my classmates really allowed me to create in a way that had absolutely no influence whatsoever from any others, resulting in the most real and authentic work I have ever created.

You’re graduating at a time when conversations around race, gender, sexuality, class and wider issues of identity have never been more prominent in fashion. How do you position your work with respect to these conversations?

As a gay Black American man living today’s reality, everything and anything I do in life is political. Whether I am directly referencing my race, gender, or sexuality in my work and in conversation, or even just doing something as simple as walking down the street, every living moment for me is positioned and situated within these narratives, whether I want it to or not. My work is entirely autobiographical and autoethnographic — in this sense, in its rawest form, I am my work. By doing the type of work that I do and creating what I create, I hope to provide new perspectives to certain narratives directly in relation to my experiences as a Black gay man, and to create celebratory spaces full of love and community.

Freyja Newsome

How would you introduce your graduate collection?

Feral scrabblings of a nymphomaniac’s last clutches at reality. Making this collection has felt very chasm-esque especially during toiling when I was locked at home with no studio access, scrambling around in my cave cultivating the bones of the clothes. It was very embryonic actually, like a period of incubation.

You’re graduating at a time when conversations around race, gender, sexuality, class and wider issues of identity have never been more prominent in fashion. How do you position your work with respect to these conversations?

Fashion has absolutely no place in any of these issues outside of extorting them for capital. I’m not going to wash my collection with any falsehoods of virtue signalling. CLOTHING, DRESS and PERSONAL STYLE however can be, and are, extremely empowering. ‘Fashion’ for me now seems like a soulless metal tin can being wound up and left to run season after season. I don’t know how you can talk about class division in fashion when fashion, in the traditional sense, is completely inaccessible to most working-class people, and when working-class people start to form our own cultures of dress they are co-opted by massive fashion houses with no regard for the original inception. So yeah, the idea of a facet of the fashion industry making work about any of these subjects and profiting off them is vile to me.

How have the past 15 months shaped your understanding of fashion’s purpose?

Making clothes has always been the purest form of escapism for me, and being stuck inside constantly swimming around my own bubbling cesspool of interests really enabled me to nosedive into my own world. I’ve matured like a really old stinky cheese and I am now even more delicious and a bit poisonous and definitely not for the faint-hearted — but that’s okay, you can’t win ‘em all, and I don’t think I want to anyway.

Luma Guarçoni Louzada

How would you introduce your graduate collection?

My graduate collection is ‘An Ode to the Gambiarra’, a practical investigation into the Gambiarra; an epistemology of design rooted in a particular socio-economic context in Brasil. It explores how non-Western design practices that take place at the margins of capitalism can be seen as counter-narratives to the Eurocentric hegemony in the design field, and seeks to understand these practices as forms of resistance against capitalist imposition and contemporary neocolonial thought as well as a fundamental tool in the process of decoloniality.

What were the most unexpected challenges and positive outcomes you experienced while creating your collection?

When the pandemic hit, I was in the first month of what was supposed to be a six-month-long field research trip around Brasil, meeting the artisans and their techniques in person. To have something I had been planning for almost two years completely collapse felt devastating at the time. I then went back to my hometown (where I hadn’t lived since I was three years old) to “wait until the pandemic ended”, and that still feels like a very far-off future for Brasil. The biggest challenges were definitely dealing with the uncertainty of what was going to happen — having to readjust to my hometown and family setting, struggling with my mental health, the absurd political context in Brasil, and so on.

The positive experiences were mostly personal, and outweigh the challenges by far. I got to reconnect with my roots, create my own memories in a place I left so early, develop mature relationships with my family on my own terms, solidify my identity as a person that inhabits spaces in the Global South and Global North simultaneously, and I got to live a whole year near the ocean — so I could always take my panic attacks to Iemanjá.

You’re graduating at a time when conversations around race, gender, sexuality, class and wider issues of identity have never been more prominent in fashion. How do you position your work with respect to these conversations?

I see my work as being intrinsically linked to my political positioning. Through investigating Gambiarra and the socioeconomic reality it’s a product of, I’m actively engaging in conversations of globalization, capitalist imposition, neocolonial thought and power dynamics within the design field. In a more practical way, the fact that the entire collection is made from artisanal materials that are ethically sourced and environmentally responsible poses the possibility of a fashion production chain as a tool for social progress. Ethical use of artisanal work can offer a multi-pronged approach to sustainability that interacts with all four pillars of it: environmentally, the traditional techniques I’ve been working with use ancestral knowledge of local nature to sustainably harvest and preserve the natural fibers they work with, or use upcycled materials; economically, the cooperatives and artisans are usually from a more vulnerable socioeconomic backgrounds, and by collaborating with them directly I can maximise their earnings and expose their work to a more affluent market that can appropriately value and financially incentivise their craft; culturally, the valorisation of traditional techniques and the process of reimagining ways for them to interact with a modern world is essential for long term preservation of ancestral knowledge; and socially, in Brazil approximately 80% of artisans are female and through their craft they find an empowerment and autonomy that is seldom available for women in rural parts of the country. In this way, artisanal techniques are a significant form of emancipation for women.

What do you hope people will take away from your collection?

I hope people begin to see the potentiality and richness of marginalised creative practices and materials, and that this presents them a new vision for what fashion could be; an inclusive decolonial tool that works for social progress.

Mathilde Schaub

How would you introduce your graduate collection?

The concept of my collection is to metamorphose the human figure into non-binary characters: mixing the bodies of a man and a woman to make one garment for both. Each character becomes a third sex or a third gender (‘HIR’), where the individual is ‘neither man nor woman’, ‘both man and woman’, or ‘neutral’. It proposes a kind of ‘collective self’, creatures of a post-gender world, where Man will be free to create his own identity, and to accept himself as ‘monstrous’.

You’re graduating at a time when conversations around race, gender, sexuality, class and wider issues of identity have never been more prominent in fashion. How do you position your work with respect to these conversations?

My collection explores issues of binary and post-gender theory, and is inspired by Donna Haraway’s feminist writing and her essay “A Cyborg Manifesto”, a work that criticises the identity politics of traditional feminism based on a binary definition of gender. She used the metaphor of the cyborg, a ‘neutral’ being, neither man, animal nor machine, to urge feminists to go beyond the limits of traditional gender. It is a call for a return to the primitive state, stripping away the constraints of Western society.

How have the past 15 months shaped your understanding of fashion’s purpose?

Fashion has always played a significant role in our lives from a sociological point of view — just look at subcultures, for example. But a garment can also be a medium to express ideas, like through patterncutting and textiles. For this collection, I wanted to create a real ‘human sculpture’ to express my ideas and commitment. Fashion must dare to address the society and the people of our times without any fear of taboo.

Steven Chevalier

How would you introduce your graduate collection?

My collection is inspired by the different cultural surroundings I’ve experienced in my life. Whether it’s people I’ve seen on the street, on public transport, or in different areas of the arts and underground party scenes, living in Paris and London has really influenced my way of thinking and my perspective on art and fashion design.

What were the most unexpected challenges and positive outcomes you experienced while creating your collection?

As I was working and living in Paris for my placement year, back at school, I had to stop thinking about creating commercial product, and go back to the very creative approach we learn at CSM. I really had to push my self to create pieces that were closer to art than clothing. Making sculptures that connected with the human body was challenging, but I really wanted to use this time at school to push my creativity to the maximum.

How have the past 15 months shaped your understanding of fashion’s purpose?

The pandemic, and the multiple periods of isolation that came with it, influenced me heavily. I’ve long been interested in interior design, and wanted to create sculptures for my own place. If found the process really inspiring and it allowed me to escape the reality of the global pandemic.

Thomas Kindon

How would you introduce your graduate collection?

The collection is an exercise of the unconscious; the tale of a nomadic warrior falling asleep on horseback into a psychedelic dream. I formed a design language by combining research into the Huns, (4th-century barbarians), with graphics of the psychedelic movement. Notions of fluidity, graphic colour, and negative space are juxtaposed with rage and ferocity. Silhouettes are slashed and elongated, referencing painful rituals that distort Hunnic profiles into a wild and threatening image. Streamlined cuts dominate the collection, drawing upon their extreme archery skills and archival editorials from the psychedelic era.

What were the most unexpected challenges and positive outcomes you experienced while creating your collection?

My biggest challenges were fabric shop closures and online pattern-cutting tutorials. Both require a lot of interaction, so having a lot more patience and being more decisive helped overcome these issues. Spending time in lockdown taught me how to prioritise. I think was a lot more sustainable than spending the whole year in the studio in the sense — everything I did was authentically me and I gave myself time off to breathe.

The biggest positive has been looking back over the year now that I am doing my portfolio and seeing my growth — how the project evolved over time. Even looking at myself, it’s quite funny how my personal style moved with the project too! And the show yesterday was such a warm experience – the cherry on the cake!

How have the past 15 months shaped your understanding of fashion’s purpose?

They’ve put a lot of things into perspective with respect to how I look at fashion and how I want others to look at my work. I wanted my final collection to be stimulating for people to see and experience — so I pushed the work beyond fashion into film and music, collaborating with friends whose work I really admire. I think this is the purpose of fashion — it’s an experience of unity and a celebration of concept and creativity. It should be used to educate and/or inspire others and it should be a joy for the designer to create, too — which it was!