If you’ve been following our fashion graduate show coverage over the past year, you’ll be aware of the cruel circumstances that the pandemic has imposed on an entire micro-generation of students. Cut off from the equipment and technical support of their school’s studios, and robbed of the runway moments they’d been working towards for years, fashion students the world over have invariably demonstrated incredible resourcefulness, skill and verve in bringing their visions to life.

The members of Central Saint Martins’ MA Fashion Class of 2021 are, of course, no exception. Having entered their degrees with dreams of showing their work in the school’s annual London Fashion Week show — without doubt one of the most eagerly observed platforms for promising talent in the industry — the way they’re showcasing their final collections is, of course, a little different to what they expected. But, as the guise that this year’s CSM MA graduate show proves, ‘different’ doesn’t mean a drop in standards.

This year, the King’s Cross institution has pulled out all the stops to create an interactive 3D exhibition, navigable from whichever screen you’re sitting behind right now. We won’t spoil it for you, but — featuring a spoken word recital by Michèle Lamy, a limited-edition photography book by Anna Fox documenting the making of the collections, and virtual white cube spaces for each of this year’s 33 graduates — it’s easily the most immersive, impressive fashion graduate showcase we’ve seen. To whet your appetite for the stylish bounty that awaits you here, we asked 10 of this year’s graduates to tell us about themselves, their collections, and how the past year has shaped their perspectives on fashion.

Adam Elyassé

How would you introduce your graduate collection? As extremes in a constant shift between products of power and pain. It’s about communication, cooperation, duality and concinnity. How did you find developing and creating your graduate collection during the pandemic? I didn’t know it at the time, but I was ready to work in isolation. I’d been romanticising the idea of this moment for years prior, which compelled me to fill my room with almost all the machinery and necessary tools I needed to complete an entire collection at home. It’s been an unorthodox journey during the pandemic, but this distant period has felt really personal. You’re graduating at a time when conversations around race, gender, sexuality, class and wider issues of identity have never been more prominent in fashion. How do you position your work with respect to these conversations? My dual identity inclines me towards representing the African diaspora in the UK, but not limiting myself to that. I placed myself in fashion at a time when it disturbed me, and I turned to my community and to craftsmanship for morale. Years later there’s a shift in conversations in the industry and for me internally. The disturbances I felt have begun to disappear, though not entirely. Tupac once said: “When they see me they know that every day when I’m breathing it’s for us to go farther. Every time I speak, I want the truth to come out.” There’s an excess of anger and passion within our community that cannot stay silent. My work comes from a place that voices the many and not the few. How has the past year shaped your understanding of fashion’s purpose? It’s been a catalyst to remove the smoke and mirrors around fashion. Subsequently, necessary conversations are being had as we search for solutions. Other than craftsmanship, I think that the most powerful thing in fashion is the ability to communicate in a way that doesn’t require words for understanding. Those who won’t hear must feel.

How would you introduce your graduate collection? It’s about dressing the type of person who feels abnormally normal being abnormally dressed, ignoring stubbornly generic dress codes and actually enjoying colour, craft and dressing up. I was hugely drawn to this idea of creating an almost childish character who explores surreal video game-like fantasies, feeling empowered to explore the most infantile version of themself and let go of toxic stereotypes. The process was quite playful and the collection turned out to be undeniably personal. It explores my obsession with raw clumsy art and nostalgic memories of childhood. You’re graduating at a time when conversations around race, gender, sexuality, class and wider issues of identity have never been more prominent in fashion. How do you position your work with respect to these conversations? My work is heavily influenced by sexuality, gender and my personal experience with my identity. With my work, I try to swap the dominant figure of imposed conventional masculinity for an infantile and imaginative alternative. While I would label myself as a menswear designer, I wouldn’t necessarily say that my work can’t be considered womenswear as well. This collection is not about ‘sexiness’ and doesn’t seek to contribute to the societal pressure of physical attractiveness. As a designer, you have to question and constantly ask yourself how you would feel about your own work from a different perspective. You need to be aware, reflect and question if your work is actually empowering or potentially causing harm. How has the past year shaped your understanding of fashion’s purpose? I believe that fashion is one of our most important tools of communication. It connects our society, and everyone that’s part of it participates in it. Even being anti-fashion is, was and always will be a fashion statement. You simply can’t not take part in the conversation.

Chaney Manshu Diao

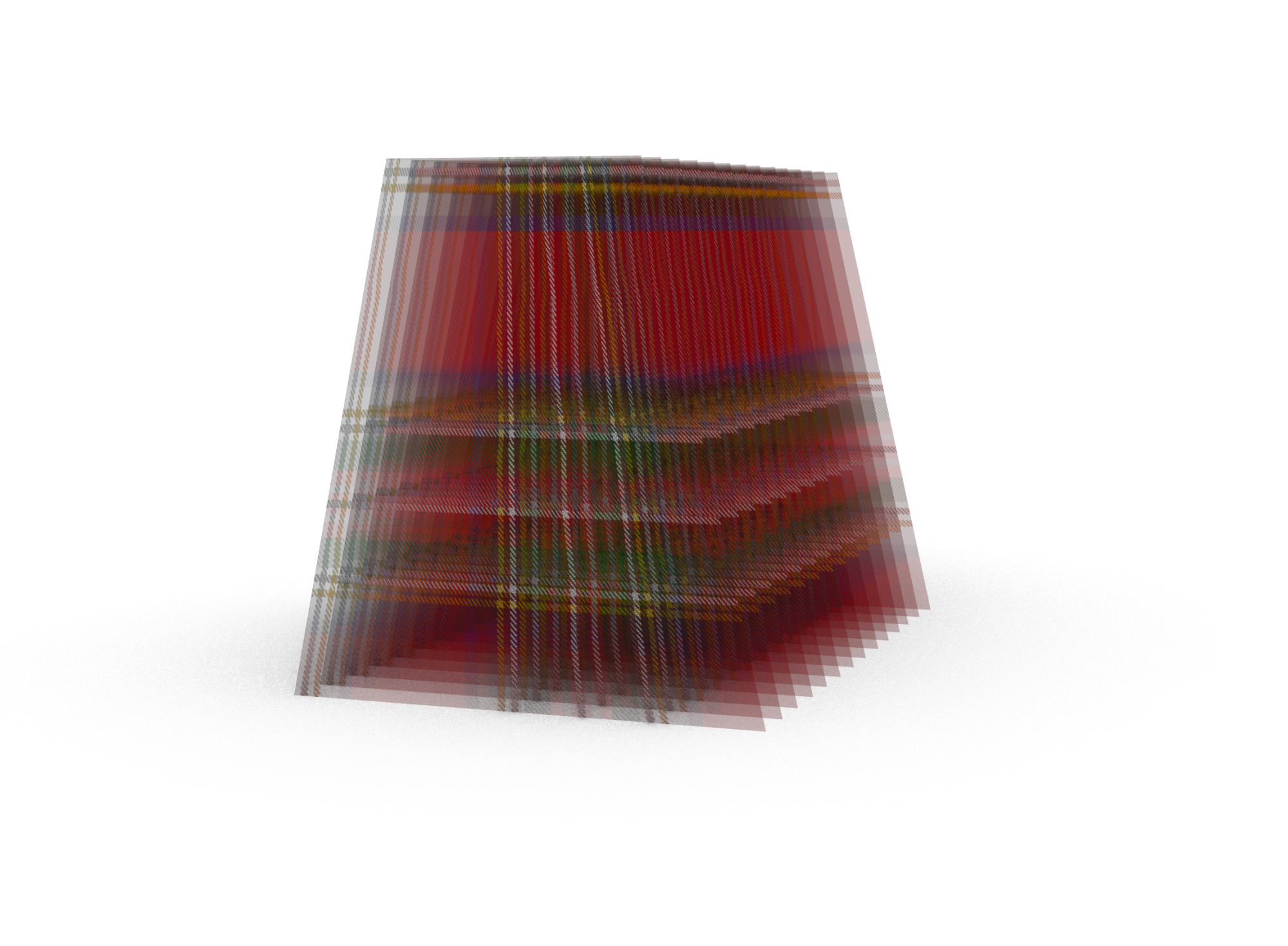

How would you introduce your graduate collection? It’s quite theoretical, yet visually straightforward and artistic. It’s a step further from my BA final collection in terms of expressing my uneasiness around the norms of wearing. Its central theme is the paradoxical relationship between the inner-self and the outer, visible self. Philosophically speaking, it’s a result of the separation of the mind and body in an object-oriented world. Sociologically speaking, it’s a result of how we are defined and perceived through others’ eyes. How did you find developing and creating your graduate collection during the pandemic? I didn’t encounter any actual disadvantages, as I decided to make a collection that is not physical. But I did suffer from the isolation and a lack of positivity, which are the main challenges I was, and still am, facing in this turbulent time. You’re graduating at a time when conversations around race, gender, sexuality, class and wider issues of identity have never been more prominent in fashion. How do you position your work with respect to these conversations? My work stands in opposition to the ‘gazing’ behaviour that’s present in every aspect of social interaction. Here, I am not trying to fight for my own identity but to question how brutally, in fashion and out of fashion, different races, genders, classes have been labelled as very flat, almost 2D impressions, and have been given social advantages or disadvantages. How has the past year shaped your understanding of fashion’s purpose? From my very personal perspective, this past year has made me believe in the artistic capacity of fashion, in its ability to welcome the transcendence of its commodity status, superficiality, and ephemerality. But, depending on the ‘form’ it takes, fashion should have more than one purpose. The term ‘fashion’ already contains multiple meanings, relating to garments, style, imagery. To me, fashion should serve the purpose of provoking, causing us to question and to think.

How would you introduce your graduate collection? The collection is about French suburbs, the South, football and romanticism. It’s influenced in equal measure by both sportswear silhouettes favoured by the youth of the small French suburb I spent much of my childhood in, as well as by traditional French textiles and craftsmanship. I wanted to tell a modern story of France… staying away from clichés of ‘Parisian chic’ and proposing a new reference point. YYou’re graduating at a time when conversations around race, gender, sexuality, class and wider issues of identity have never been more prominent in fashion. How do you position your work with respect to these conversations? I wanted to open up what we know about French culture; I wanted to give insight into my country’s diversity and dynamism. Secondly, as a girl doing menswear, it was interesting for me to approach ‘masculinity’ through a tender prism. A friend of mine described the collection as ‘sensitive sportswear’, which I quite like. Claiming tenderness as cool is, to me, quite progressive… and sexy 😉 How has the past year shaped your understanding of fashion’s purpose? Make trackies not dresses lol! Comfort is key.

How would you introduce your graduate collection? It’s a fusion of the British countryside and city. Looking at materials and garments associated with history and the symbols of the upper class (18th Century military dress, hunting attire) and repurposing them to apply to the street. It’s about the idea of treating the formal in an informal way, and taking the control and structure out of things; seeing how materials and garments associated with British tradition can be appropriated by casual clothing. Classic films like Barry Lyndon and Trainspotting, made me look at the idea of a character’s free will, or lack of it, and how that plays out in their life depending on the circumstance they were born into. You’re graduating at a time when conversations around race, gender, sexuality, class and wider issues of identity have never been more prominent in fashion. How do you position your work with respect to these conversations? This collection is meant to make the inaccessible accessible. I was evaluating where masculine power lies in the elite and then looking at ways to break it down and soften it — something that I think is slowly starting to happen with all aspects of culture at this moment in time. How has the past year shaped your understanding of fashion’s purpose? It’s made me realise the extent to which it’s not a stand-alone thing. It exists to interact with people and the outside world, but I don’t know yet what that interaction will look like after this is over — I’m waiting to see.

How would you introduce your graduate collection? ’Tomoe’ is a reaction to escapism and liberation, inspired by the cross-cultural influences of British and Japanese 80s New Wave Bands. Think if ‘King Arthur’ and ‘Tomoe Gozen’ teamed up as an unexpected duo in a Kill Bill-style movie! You’re graduating at a time when conversations around race, gender, sexuality, class and wider issues of identity have never been more prominent in fashion. How do you position your work with respect to these conversations? My collection really started when I read an article discussing how British New Wave bands used fashion and music as a form of escapism from their surroundings, both geographically and from limitations due to class imposed by Thatcher. During the pandemic, it has felt like students, particularly in the creative arts have had little certainty or support, and I have felt an intense estrangement from the people who are running this country. 80s New Wave bands used dressing to project nuances onto high society menswear, seeming to almost queer it — like Duran Duran’s “Seven and the Ragged Tiger” album cover. In a similar way, I wanted to embody the high-class dress codes seen in the likes of Dafydd Jones’ images, and utilise them as a kind of armour. How has the past year shaped your understanding of fashion’s purpose? When the pandemic hit, I felt like what I was doing lost meaning and really found it hard to find the motivation to create something I felt connected to. I think that as the year progressed, though, people started turning to art and fashion for a sense of escape and entertainment. Fashion isn’t a necessity, but it’s definitely crucial for people to express themselves.

How would you introduce your graduate collection? My graduate collection is an action as well as a reaction. ‘Cheers, j’ai de la Fortune’, also known as SHEER GOOD FORTUNE, is a collection of ideas rather than a collection of clothes. It’s about: Generation. RE-Generation. Self-Sufficiency. How did you find developing and creating your graduate collection during the pandemic? I don’t really want to talk too much on how hard it was, because the way I truly feel is: blessed. I was privileged enough to be in education, rocked like a baby within a system. Neither worrying about having lost my job, nor being expelled from my flat. You’re graduating at a time when conversations around race, gender, sexuality, class and wider issues of identity have never been more prominent in fashion. How do you position your work with respect to these conversations? All these topics are meaningful conversations that fashion designers can’t avoid having anymore. We are identity workers. Identity barometers. We ask: ‘Who are you? How do you feel in those clothes? Do you think I have understood your attitude better than you have yourself?’ The conversation starts with ALL identities. One designer can’t pretend to be able to talk to half the planet. We need thousands of designers for everybody to be included. I think permitting thousands of designers to exist is permitting people to understand that each being a unique case is far more inclusive than everyone being part of a homogeneous majority. Regarding class, I do agree with The White Pube’s posters: it would be interesting to voice if our parents’ wealth helped us in getting where we are. It is not about shaming privilege; it’s about raising awareness, and almost gathering statistics about the reality of the industry. If we want it to change, it starts with honesty. After stating this, I feel like it’s my turn to express my personal position. I am from a privately educated background. The left-wing environment is the one I chose for myself, not the one I was raised in. Is being privileged a problem? Or is the problem what you do with your privilege? Allow me my past, make me responsible for my future.

Tasha Sweeney

How would you introduce your graduate collection? My collection is a series of hybrid garments that fuse the energy of the street with traditional Northern heritage, inspired by my family’s obsession with Everton Football Club, passed down for generations. It examines the relationship between sportswear and femininity and considers how the interior details can be worn on the outside and how this can affect or manipulate the silhouette. My aim was to create a collection that can be worn in a variety of ways — no garment has to be paired with the other, anything can be worn together. It’s an approach I use to dress myself. You’re graduating at a time when conversations around race, gender, sexuality, class and wider issues of identity have never been more prominent in fashion. How do you position your work with respect to these conversations? All of my work is always rooted in my Northern upbringing. Being from Liverpool and growing up in a working-class environment, it has a stronghold on my work aesthetic. Going to such a prestigious university as Central Saint Martins, I became more conscious of class. Before moving to London and going to university, I had never noticed how prevalent class divisions are within institutions such as universities. I feel that my work is a response to this and my own struggles as a result of my class. How has the past year shaped your understanding of fashion’s purpose? It made me reevaluate everything I do. Sustainability has always been important to me in my design process, but during lockdown, I was unable to buy yarns. Using dead-stock yarns from previous projects was the only option for me. With the final lockdown coming to an end, I think we can all be hopeful that there is a new outlook for how we see fashion. The past year has made me emphasise the fun element of creating collections; collections that are energetic and make people smile in a time when we all need it.

How would you introduce your graduate collection? I was inspired by images of Body Horror in art and cinema that depict the ultimate loss of control. Forms breaking free of the body, creating new and unwanted shapes and selves; disorder emerging from order. My goal is to engineer chaos in the heart of the familiar. How did you find developing and creating your graduate collection during the pandemic? It was a time for reflection for me. The pandemic has brought about so much sadness and dread: I felt I needed to be still, to be alone, and to think. What I struggled with most was hope and the lack of it. The main challenge was staying positive and not dwelling in sadness. So I read a lot, dreamt a lot, spoke a lot to family and friends, all of which helped this collection come to fruition. You’re graduating at a time when conversations around race, gender, sexuality, class and wider issues of identity have never been more prominent in fashion. How do you position your work with respect to these conversations? These conversations are helping to ground and educate an industry that would not have been so welcoming to someone who looks like me in the past. At the same time, I want to challenge ideas people might have of how Black women should design, purely on the basis of their race, gender, and background. Through my work, I want to show there is more than one way to own your identity. I do not have to live out preconceived notions of my identity to be heard – my identity reveals itself through various details in my work, from research to construction to end product. How has the past year shaped your understanding of fashion’s purpose? During the past year, I became quite confused about this, but now it makes sense to me. Hope is the first word that comes to mind. Fashion has a responsibility to bring people together as dreamers and thinkers and readers. Fashion’s purpose in doing this is to help us bridge the gaps between reality and fantasy.

Vivien Canadas

How would you introduce your graduate collection? It’s called “A sip of fresh air”. From the heart of the city, it’s an escape to a fantasy countryside — a playful and personal invitation for a city getaway. In less than a century, humanity has completely transformed its natural habitat by escaping the countryside in favour of the city. It’s a radical mutation that has cultivated some sort of nostalgia. My collection explores how the ideal of a life in the countryside redefines and transforms the concept of modernity. A celebration of the bridge between traditions and mankind’s (odd?) progress. The wind is blowing, full skirts are flying, coats are pushed against the front of the body. “A sip of fresh air” is also about reiterating our temperamental relationships to the elements. You’re graduating at a time when conversations around race, gender, sexuality, class and wider issues of identity have never been more prominent in fashion. How do you position your work with respect to these conversations? As fashion designers we are not only developing garments, we are creating a world. It is essential to take part in these ongoing conversations and reflect on the messages we’re spreading through our work. In my process, it was essential for me to understand who I am and what I represent in order to put out a progressive message that acknowledges and elevates others, irrespective of gender, race, sexuality, et cetera. How has the past year shaped your understanding of fashion’s purpose? Fashion is about sharing. It is a human adventure that reaches its fullest when you get to collaborate, interact and create with others.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more fashion.

Credits

All images courtesy of the designers