Halston, Charles James, Calvin Klein, Tommy Hilfiger, Tom Ford… you’re already familiar with the usual protagonists in America’s fashion story; the designers that are cited as the bedrock of the nation’s industry. And they are an integral part of it. But in the privileging of a coterie of mostly white, mostly male designers, swathes of vital contributors to the tale of how we got to where we are today have been systematically overlooked. Over the next 12 months, The Met’s Costume Institute will open a two-part exhibition that has the potential to rectify that. In America: A Lexicon of Fashion, opening in September 2021, and In America: An Anthology of Fashion, opening in May 2022, could address and go some way towards remedying the imbalanced perspectives that have shaped our understanding of American fashion.

Even if it is not a result of explicit intention, the Costume Institute, like many institutions that stage fashion exhibitions, has arguably played a part in contributing to this skewed view of American fashion history. By reproducing implicit biases entrenched in wider society, it has reflected a white-centric narrative that has long been taken as a given. As Vanessa Friedman illustrated in a recent article for The New York Times, “at the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, none of the named designers in the three pages of online “highlights” from the 33,000-piece collection are Black”. And it’s hardly an issue confined to the New York institution; at the Palais Galliera in Paris, only 77 out of its collection of 200,000 objects are by Black designers. In the wake of America’s reckoning with entrenched systemic racism and inequity, the duty of the country’s fashion industry to acknowledge the impactful roles played by individuals belonging to marginalised communities has come into sharp focus. In turn, conversations around the need for truly diverse representation in the upcoming Met exhibition have come to the fore.

“There are so many designers, especially designers of colour and Black designers that don’t get their dues in any sort of context, especially in American fashion history,” concurs Luke Meagher, a fashion commentator and YouTuber. “I’d love to see research on designers like Patrick Kelly, Stephen Burrows, Zelda Wynn Valdes, Anna Sui,” he continues, drawing attention to the plural voices that have shaped the course of American fashion. These voices also include formerly enslaved dressmakers in the 19th century and Arthur McGee in the 1950s and 1960s; modest fashion designers like Nzinga Knight, a Black Muslim woman, and contemporary Asian American designers like Peter Do and the trio behind Commission NYC; Jewish immigrant Jacob Davis, who designed the rivet-lined jeans patented by Levi Strauss in 1873, and Black designers like Dapper Dan, April Walker and Willi Smith, who played essential roles in the development of the category we now call ‘streetwear’.

“Something else that is very important is the inclusion of designers who are descendants of the First Nations of America,” Luke says, noting the general lack of awareness around the historical contributions of Indigenous figures to contemporary fashion — the remarkable, romantic work of Navajo designer Orlando Dugi, for example, or the elaborately patterned collections of Northern Cheyenne/Crow designer Bethany Yellowtail. These are just a few of the names in the “anthology” of American fashion history that this exhibition has a duty to explore, especially in the time we currently live.

“Some of the most crucial moments in American fashion history have taken place beyond gilded runways — which is exactly what makes it so special.”

Of course, there is only so much that any given exhibition can contain, and there are features that some deem important that will be omitted. Still, it is exactly this inevitable truth — one that is inherent to curatorial practice — that makes questioning the motives behind each inclusion so important. “Everyone who chooses to work in museums should be grappling with the institutional context of exhibitions, the legacies of exclusion, the biases of predominantly white museum staff,” says Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, the curator of contemporary design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum and curator of Willi Smith: Street Couture, the show currently on view at the Upper East Side institution.

In light of the exhibition’s remit to explore the legacy of the legendary Black American designer, she saw her task as one of creating space for narratives not typically seen in Eurocentric-leaning institutions, while delivering abundant and inspiring content to as wide an audience as possible. This task, of course, was not without its challenges. “After fully grasping the importance of [Willi’s] work, I certainly questioned whether I was equipped, and the museum was equipped, to interpret his experience as a gay Black man without his guidance. Willi Smith: Street Couture became about understanding Willi Smith through a community, rather than through an institutional lens,” she says, turning the space into an arena for Willi’s story to be told on its own terms.

Listening to Andrew Bolton, the Wendy Yu Chief Curator of the Costume Institute, speak during the Met exhibition’s official press presentation, it appeared that he and his team have adopted a similarly expansive approach, geared more towards embracing polyvocality than imposing a definitive, singular narrative. The first part of the exhibition, In America: A Lexicon of Fashion, sets out with the intention of “establishing a lexicon of American fashion based on the emotional qualities of dress”, he says, creating “a new vocabulary that’s more relevant and more reflexive at the time in which we’re living”. This notion is then to be expanded on in the second part, In America: An Anthology of Fashion, which will open further discussions around the cultural vibrancy of, and unsung heroes within, America’s fashion canon.

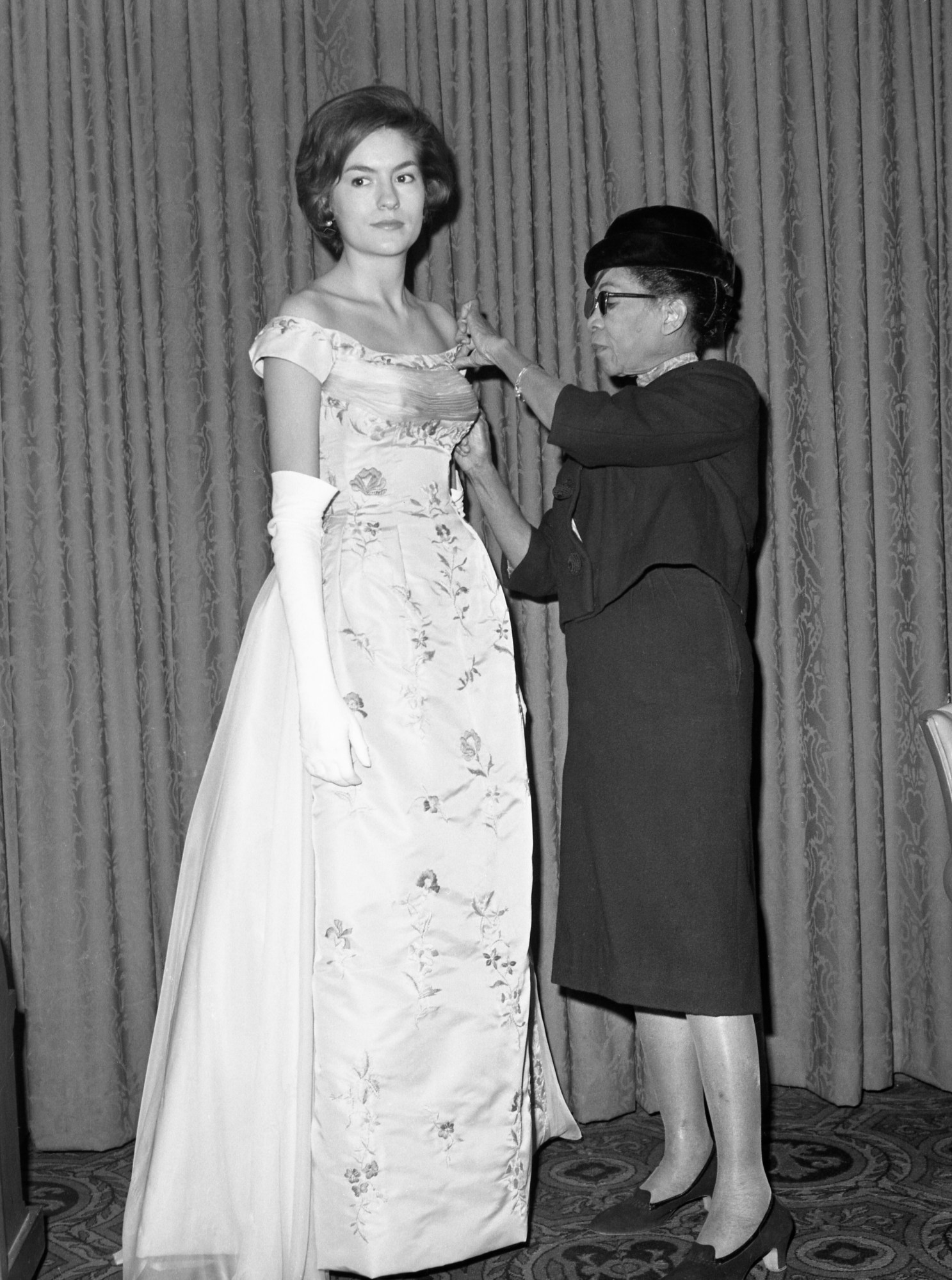

“It has been mentioned that the curators plan to include the stories of Elizabeth Keckley and Fannie Criss,” says fashion scholar Rikki Byrd, the former being Mary Todd Lincoln’s dressmaker and the latter being a renowned designer for the elite. Both, it bears noting, were Black women. “I’m interested in how they will share their stories while also acknowledging the many Black seamstresses born during the same period whose names we don’t know,” Rikki continues. She mentions Ann Lowe — the designer of Jackie Kennedy’s wedding dress, who was only ever credited as “a coloured woman” during the socialite’s lifetime — and Lois K. Lane-Alexander, a designer and founder of the now-defunct Black Fashion Museum (the collection of which was acquired by the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture), as stories that she hopes to see told.

Indeed, in the wake of conversations around the disproportionate representation of the Black community at the industry’s heights, the essential contributions of Black designers to American fashion history is something that must be boldly illustrated throughout both parts of the exhibition. This is, it bears noting, a responsibility that extends beyond the inclusion of contemporary designers like Virgil Abloh, Shayne Oliver, Telfar, Christopher John Rogers and Kerby Jean-Raymond, crucial as they are in shaping the American fashion landscape today. Historical landmarks like the 1973 “Battle of Versailles”, a fundraising event for the French palace that pitted five leading American designers of the era against five of their foremost Gallic counterparts, are important in this respect. While attention is often placed on the participation of Halston and Bill Blass, as seen in the recent Netflix mini-series Halston, the crucial role the event played in expanding the reach of the American fashion industry is in part due to the ingenuity of Black American designer Stephen Burrows, as well as a league of Black supermodels such as Pat Cleveland, Bethann Hardison and Billie Blair. And then there’s Oscar de la Renta, the Battle’s sole Latinx designer, whose romantic silhouettes set new benchmarks in American ready-to-wear from the 1960s onward.

Not to mention that some of the most crucial moments in American fashion history have taken place beyond gilded runways — which is exactly what makes it so special. It is filled with examples of designers working beyond the parameters of convention, leading the charge in using fashion as a means to engage with and shape ideas around gender-neutrality, activism, and street culture, for example. Willy Chavarria — a designer known for fusing social justice and design in his denim ensembles and Chicano streetwear-inspired collections, and the recently-appointed Senior Vice President of Design at Calvin Klein — and urban wear companies like WalkerWear, FUBU, and Cross Colours are cases in point. They embody how inspirations from the streets of various communities, particularly marginalised ones, have intermingled over the past 75 years to create the distinct spirit of American fashion today, which has made its mark in Paris, Milan, London and beyond.

Standing beside a billowing taffeta Christopher John Rogers gown, an Andre Walker wool frock, and a cotton poplin dress by Prabal Gurung during the Costume Institute’s virtual press presentation, Andrew Bolton concurs. “This past year confirms […] that American fashion is undergoing a renaissance; that the fashion industry globally is experiencing a process of reinvention and self-reflection, and American designers are embracing this fully at this moment of possibilities,” he says. But, just as designers are engaging in this process, so too must the institutions that contextualise and offer the public access to their work. That the stakes are high for the upcoming Costume Institute exhibition is a given — at the same time, the opportunity for one of the world’s greatest stages for fashion studies to show that its reputation is deserved, and not simply assumed, is unparalleled. In his presentation, Andrew mentions that the Costume Institute’s original mandate was to celebrate the American fashion industry. Seventy-five years on from its founding, we hope that In America will do exactly that.