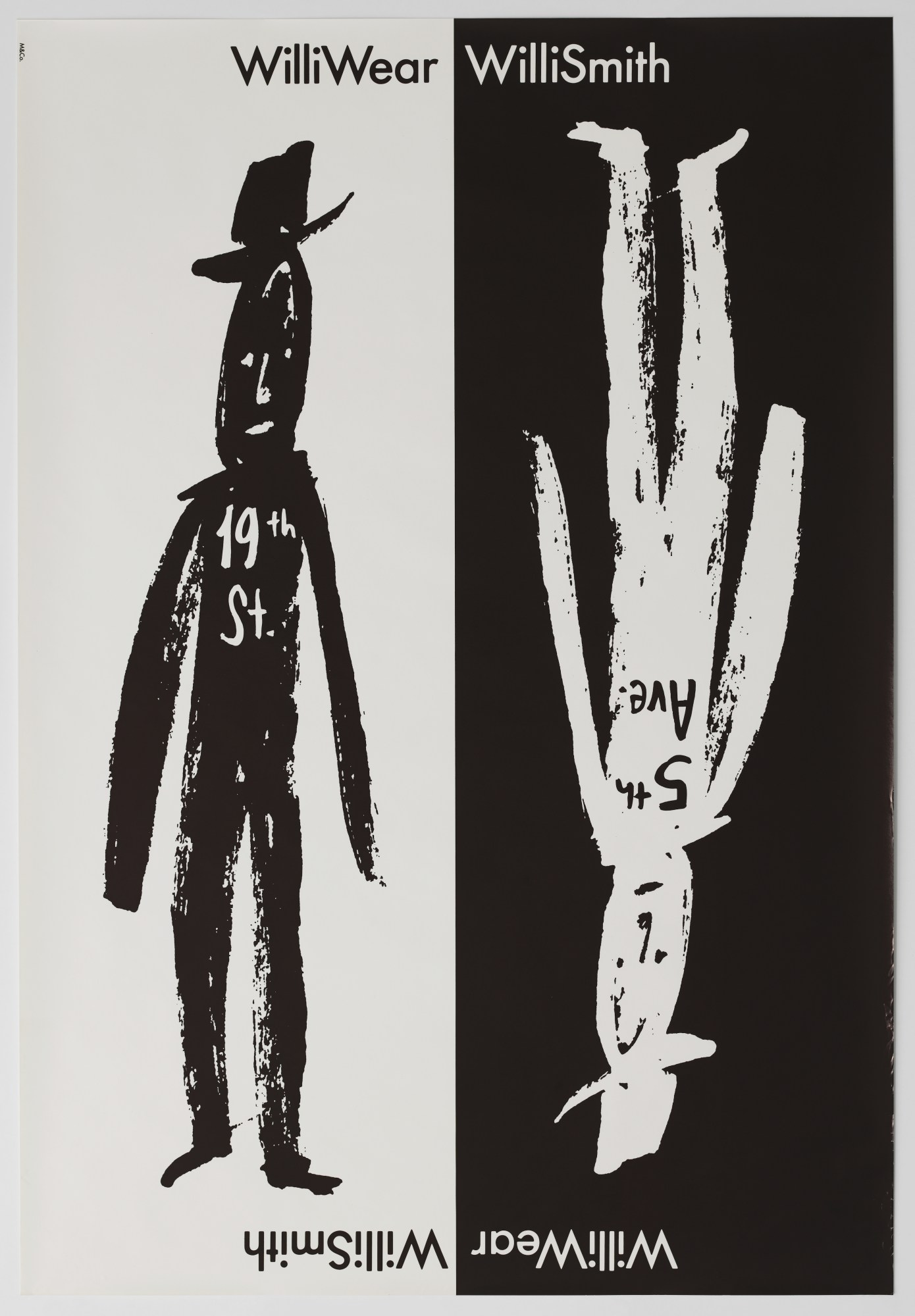

Willi Donnel Smith, founder of WilliWear, was at his peak in 1987, with his label grossing an approximate $25 million in sales. A Black, openly gay and widely-revered designer, he’d managed to carve out a forceful identity that influenced fashion the world over from his Seventh Avenue perch. An inherent sense for what the everyperson wanted to wear allowed him to confidently strike through antiquated ideas of luxury, creating what he dubbed ‘Street Couture’. “He was taking what was on the street and putting it on the runway, to give back to the street. Not as an artistic concept for high-end clientele, but as a means of bringing people with diverse lifestyles what they needed to face the world,” says Alexandra Cunningham-Cameron, curator of Willi Smith: Street Couture, a recent exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York that lives on as a book and digital archive.

Willi believed that fashion should be affordable, accessible and explorative, seeking new means of expression in collaboration with art, dance, music and film. Staunchly democratic in his approach, he reshaped ideas around what fashion was and what it could be, inviting everyone from members of the downtown ballroom circuits — as attested by an honourable mention of the brand in FX’s Pose — to the townhouse dwellers uptown. In its 10 years of existence, the WilliWear brand paved the way for a multifaceted approach to design that relied on elevating the everyday, sowing the seeds that designers like Kerby Jean Raymond, Virgil Abloh, Samuel Ross and Telfar now reap. Despite his success, however, when we discuss the evolution of the fashion landscape, and the American designers who have significantly contributed to it, his name figures on the lips of very few. “Willi Smith was the first to do things that no one had ever done before,” recalls Bethann Hardison, confidante, muse and one-time assistant of Willi’s. “And Patrick Kelly! He was the first to go to Paris as an American designer and be part of the Chambre Syndicale. Not just Black American, but American! When these things happen with people of colour, they get lost. People don’t know, they don’t remember, and any new kid on the block is suddenly the next big thing.”

Born in Philadelphia, 1948, Willi was a bookworm and an artistic child with the full support of his parents. In 1965, his grandmother, Gladys ‘Nana’ Bush, secured him an internship with Canadian couturier Arnold Scaasi through the connections of a family whose home she cleaned. It was his first taste of the cutting room floor, making clothing for ladies of note like Brooke Astor and Elizabeth Taylor. That same year, he relocated to New York City and enrolled on the fashion programme at Parsons School of Design, where he studied for two years before being expelled for an alleged affair with another male student. He quickly found work in the Garment District, hopping from one design role to another, the most notable of this period being his tenure as a designer at Glenora Juniors from 1968 followed by a post as head designer at sportswear brand Digits in 1969. The following year he would meet Laurie Mallet, his future business partner, and hire her as his design assistant in 1971. “There were many little tribes on different levels of society but then it all merged in the music, the dance and the discos,” Pat Cleveland, a friend of and model for Willi, recalls of the seventies. “That was the best social scene. Going out to Fire Island where all the designers, architects, writers and models were merging. No door was locked!”

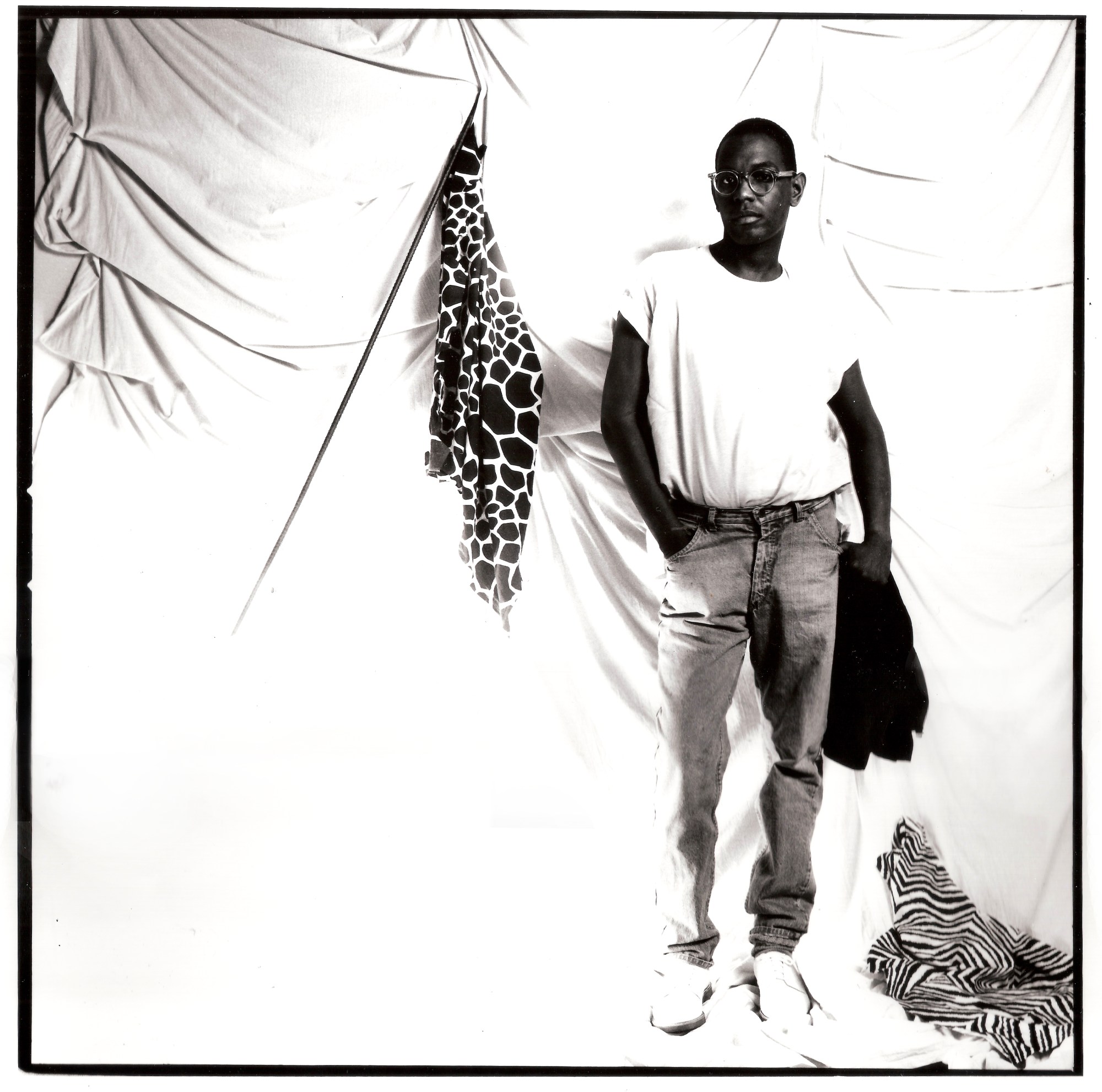

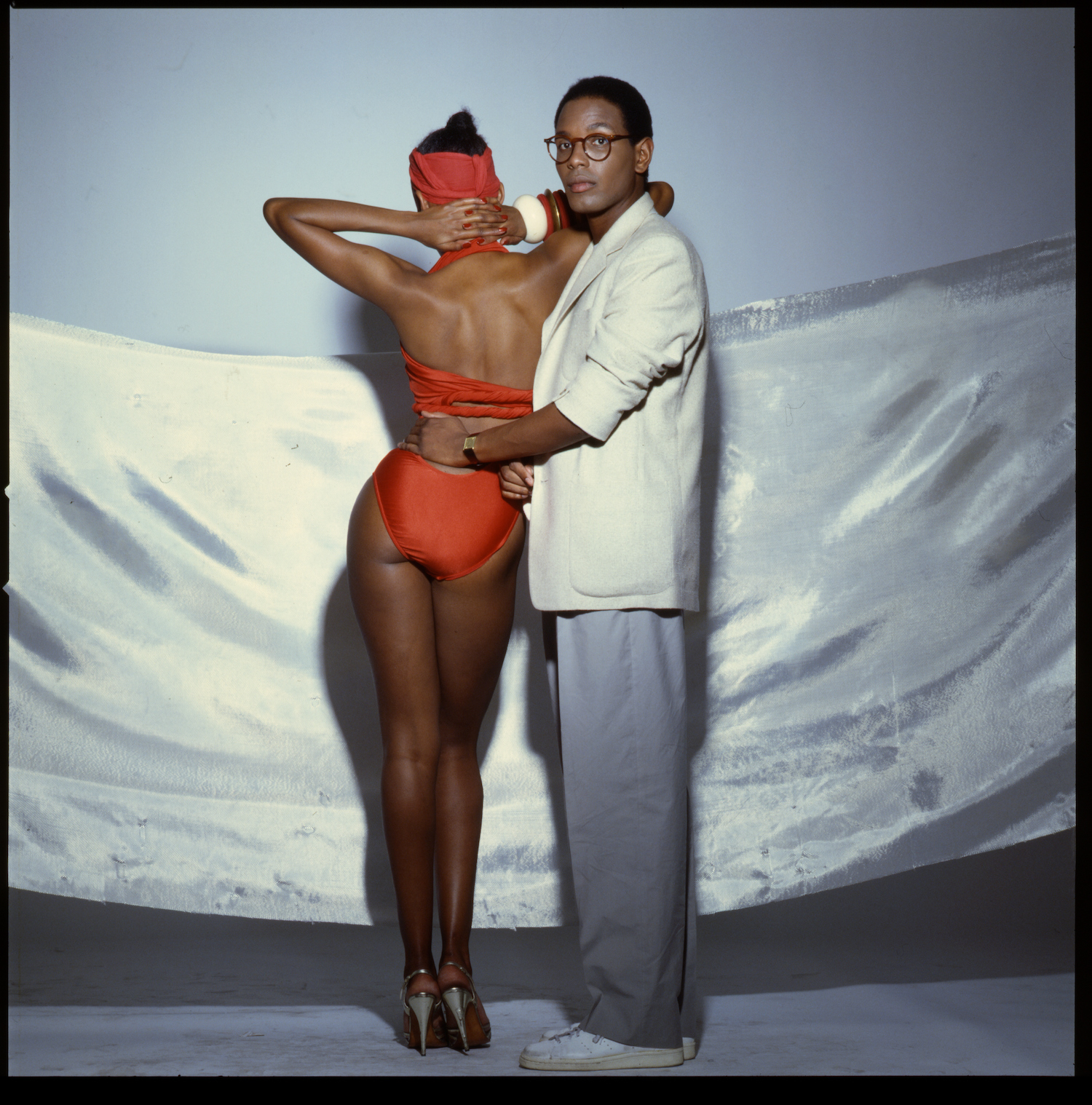

By 1976, with Laurie’s help, WilliWear was born. Returning from a trip to Mumbai, they brought with them a collection of four basic garments: a jacket, a shirt, a skirt and his infamous high-waisted and relaxed fit ‘WilliWear Pant’. “He was a great pant maker. There are only a few people who made pants that fit really well. I always gave that to Kenzo, God rest his soul, and Willi,” says Bethann. He was equally deft with unisex designs that were “architecturally done,” explains Pat. “It was cut and draped for that figure, it wasn’t like you took a top and put it on a girl, and you took a girl’s top and put it on a boy. No, it was cut for those figures, but they were like twins.”

What set WilliWear apart was his refusal to define his audience and what they should wear. While Ralph Lauren dangled old money prestige to a WASPy new money clientele with preppy signatures, respectable clothing and wholesome American tact, Willi Smith eschewed elitist branding and embraced commercialism with the same zeal as adherents to the pop art movement did before him. And while Bill Blass was devoted to cavorting with and dressing New York’s uptown it-clique in clothes that communicated the excess of their ever-accumulating wealth, Willi Smith mingled downtown with the artists he admired. “The reason that Willi was considered ‘street’, was because everyone in the street owned WilliWear and wore WilliWear,” notes Bethann. Alternatively, he provided a range of means to define yourself, however you saw fit, ideas echoed today in the free-for-all fashions of Stefano Pilati’s Random identities, Telfar and Eckhaus Latta. “He loved Sonia Rykiel, Betsey Johnson, Stephen Burrows, he admired and respected so many designers of his time. Arthur McGee was one of his mentors. But he and Laurie had a very different vision for the role that fashion needed to serve in daily life,” says Alexandra.

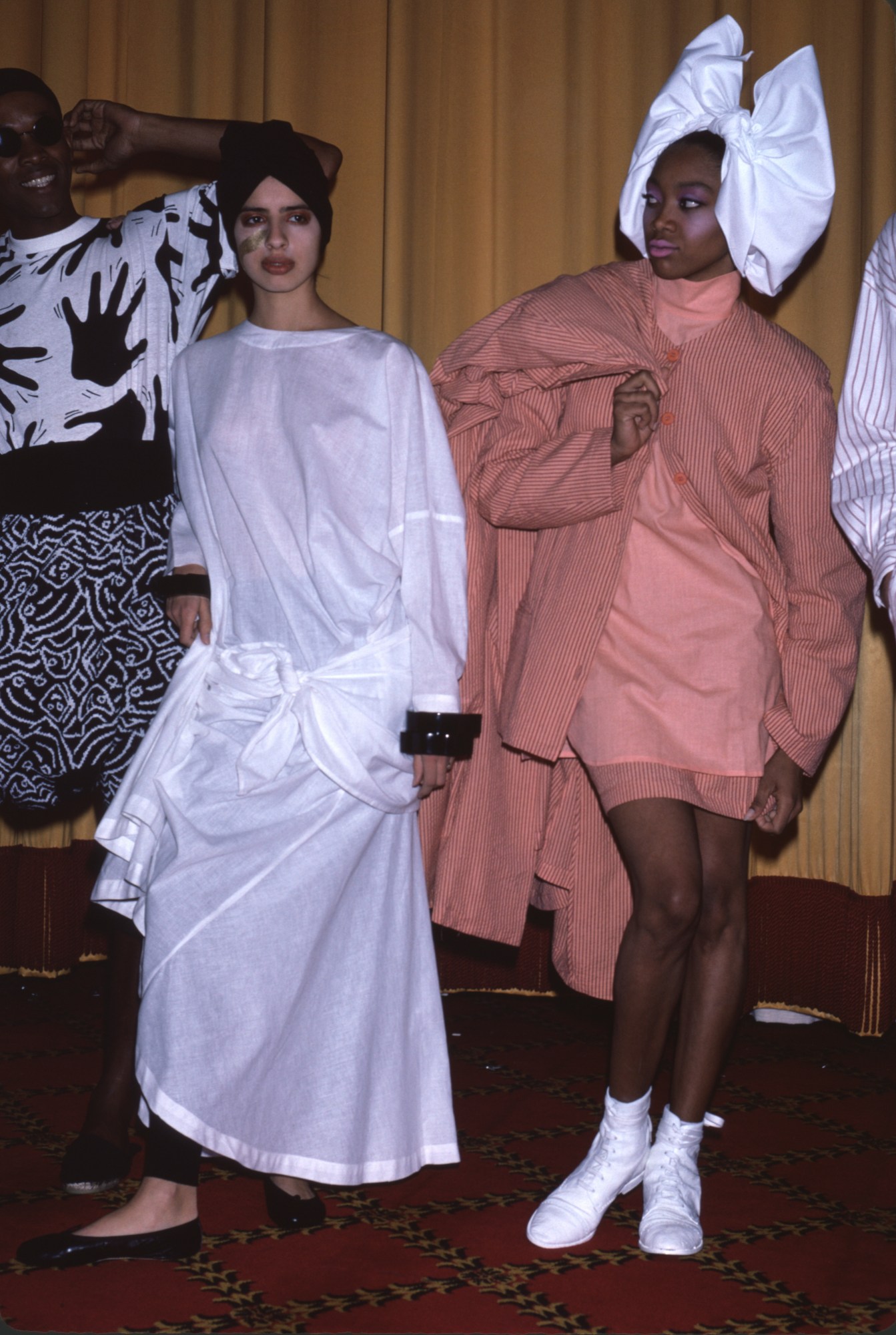

There was a country club WilliWear, a Caribbean-inspired WilliWear, and in 1986, an African WilliWear inspired by his trip to Senegal in 1985, during which he produced ‘Expedition’, a short film in collaboration with photographer Max Vadukul and scored by Peter Gordon. Thirty years later, experimental fashion films like Grace Wales Bonner’s Harley Weir-shot and Dev Hynes-scored ‘Practice’ (2017) evoke the same notions of exploring the complexity of cultural identity through fashion and style. In Willi’s film, models were street-cast and draped in neatly coiffed headwraps, bodypaint, pastel tailored suits with pith helmets and saturated wax prints; a concoction of European and African styles he wanted to both reflect on and encourage his audiences to explore. It was one of the first instances in which a fashion film was used in lieu of a runway show — odd for its time indeed, yet a prescient foreshadowing of how the fashion presentation formats we’ve grown used to in today’s COVID-culture. “He was a designer way ahead of his time. As a person, he was really very, very nice and not bitter and twisted like most designers!” says fashion journalist Michael Roberts. “Willi and his sister Toukie were a dynamic force at the time. Breaking the mould.”

Contributing factors in his ability to do so were his innate curiosity and artistic sensibility. He was a member of a burgeoning artistic milieu in Lower Manhattan, and in the same year he was expelled from Parsons, he met and collaborated with artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude on their seminal work The Wedding Dress. When the artistic duo set about enclosing eleven small islands in hot-pink polypropylene in Biscayne Bay, Miami, Willi was on hand to produce uniforms and merchandise. When they wrapped the Pont-Neuf in Paris, he designed a sky blue, loose-fitting smock modelled after the iconic bleu de travail French worker jacket. “He was the guy, he crossed so many things. Not merely the apparel business, but the arts, so many facets of it. He worked with Bill T. Jones. He was the one who dressed (Edwin) Schlossberg to marry Caroline Kennedy,” Bethann remarks.

In 1982, he participated in a multidisciplinary program at Project Space One (now MoMA PS1) in which he exhibited his installation ‘Art as Damaged Goods’. Plastered clothing was laid out on the floor, flagged with evidence markers, and completely stripped of any recognisable fashion pretext. Through WilliWear News, a zine created in collaboration with friend and Paper Magazine co-founder, Kim Hastreiter, Willi linked his clothing with film, contemporary art and nightlife. In 1984, Willi and Laurie reached out to twenty avant-garde artists (including Keith Haring, Futura 2000, Nam June Paik, Jenny Holzer and a then-unknown Barbara Kruger) to design t-shirts under his new ‘WilliWear Productions’ art venture. Aiming to bring the spirit of “high art” to those who roamed the high streets, the t-shirts — all one-size-fits-all — were set on pieces of cardboard and cellophane wrapped, selling for $37 and exhibited at the Ronald Feldman Gallery in SoHo. It’s the blueprint for the likes of Uniqlo UT initiative, which has adopted the humble t-shirt as a canvas for artists including Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Takashi Murakami and Futura 2000. It also set a precedent for the kinds of collaborations we see so many of today, those that set out to bridge the gap between established high culture and what once considered underground. It begs the question: without Willi Smith, would we have seen Kim Jones’ pairing up with Supreme while at Louis Vuitton, or with Shawn Stüssy at Dior? “The breadth of who he was connected to and who respected or liked him was very interesting for a young man of colour. He was atypical. Very kind, very smart, very charismatic, very thoughtful. He was very special. Beautiful boy, too,” says Bethann.

After a buying trip to India in 1987, Willi contracted shigella and pneumonia and was hospitalised at Mount Sinai Hospital upon his return. He died the next day, in part due to AIDS-related complications, his life and thriving career abruptly ended at the age of 39. It’s unclear whether he knew of his diagnosis, or simply suppressed the fact, like many queer people at the time. “His career was so short, like one of those flying stars. He’s like that one candle on the cake that started burning bright and everybody was wishing on it,” recalls Pat.

Still, despite Willi Smith’s sudden, tragic death, his spirit lives on and continues to inform fashion as we know it today. When Telfar won the 2017 CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund, the brand was recognised for its suggestive slits and exposé cut-outs, asymmetrical lines and unisex positioning but especially praised for its “Not for you, for everyone” mantra; in 1983, WilliWear was awarded the American Fashion Critics’ Award by the CFDA (then Coty) for similar brand ideals. There was the troupe of blonde-haired voguers who closed Hood By Air’s AW14 show, calling Willi’s love for dance to mind — often his models would skip, twirl and dance down the runway, an unusual occurrence at the time. And when Samuel Ross of A-Cold-Wall* was tapped as a “friend of the brand” by Hublot this month, they noted “his multi-faceted approach” as well as the “collaborative approach to his work; combining object design, social design and garment design, and his ability to use them as mediums of connectivity” — à la Willi Smith, indeed. Even Virgil Abloh’s AMO-designed stores recall Willi’s collaborations with SITE architects on his showrooms. “In terms of how he’s had an influence, you know, you wouldn’t have Martin Margiela’s unconventional early 90s runway shows or white-out boutique aesthetic without WilliWear. You wouldn’t have Demna’s basic list of Vetements without WilliWear, or Eckhaus Latta’s gender-neutral sizing. Pyer Moss’ “This is an Intervention” film on police brutality opening a runway show…I don’t think you’d have any of that without Willi Smith,” says Alexandra.

Perspective broadens with hindsight, with histories that have long been forgotten rising to the surface to contextualise the world we know today. Thanks to the first major retrospective of his work at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, the life and work of Willi Smith is being brought to light and gaining the recognition it deserves. “For those who come out as creatives, it’s very important to remember, and remind people that before them, there were others,” says Bethann. “And there were others before them. I saw Virgil said something recently like ‘We’re going to be the first generation to move the needle’. And I’m thinking…no, you’re not because the needle has been moving all along.”