“My godparents are from Louisiana, so I always thought of New Orleans as my God city,” Sultana Isham says. The composer and scholar, known best for her work in film, moved to the gothic Louisiana city after college. Something was pulling her there, away from her native Virginia or the roots she set up in college in New York. New Orleans is the focus of her current project: a multi-modal exploration of a club barely anybody has heard of, but that holds the key to how trans women were seen in the American south across nearly six decades.

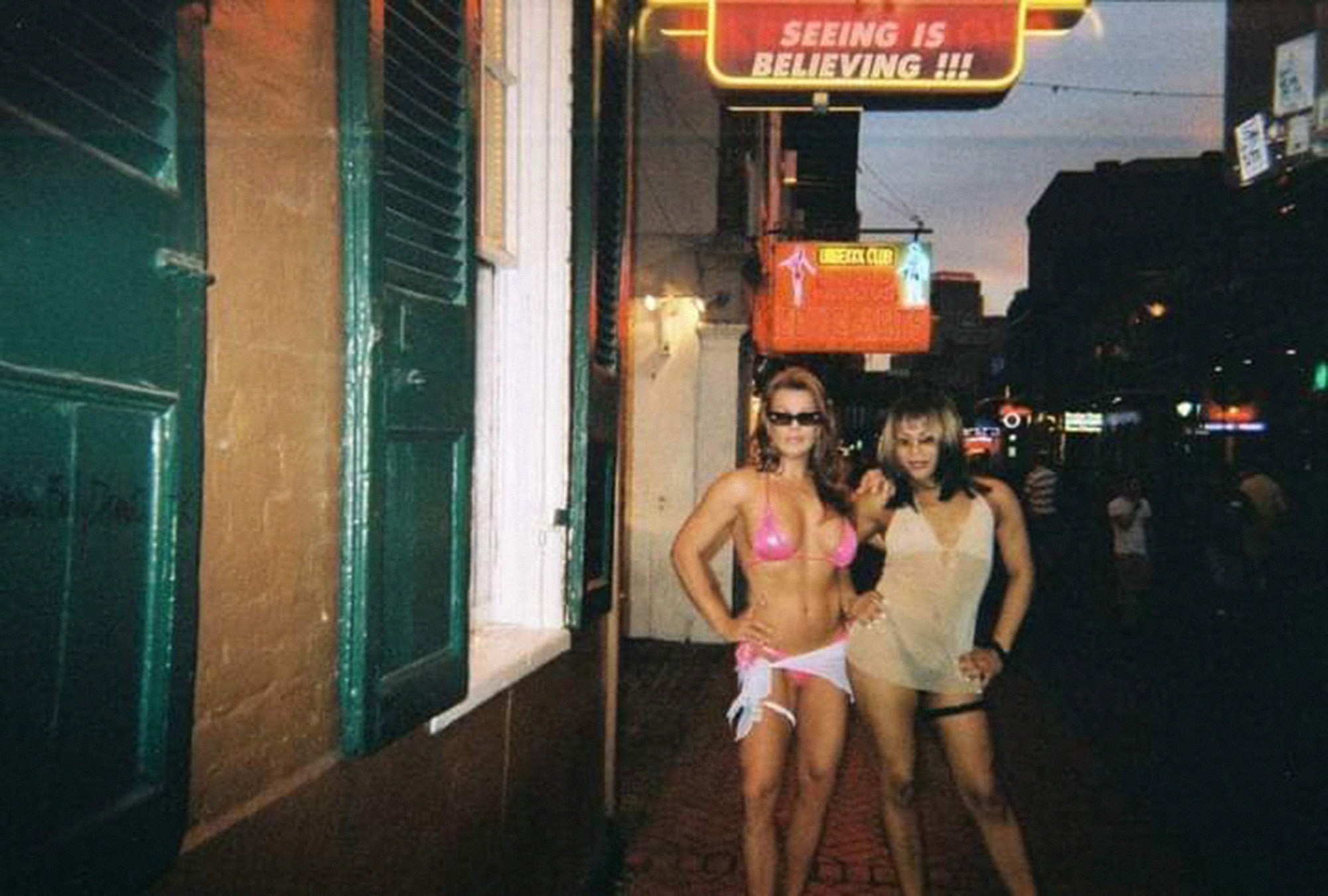

In the 1950s, Papa Joe’s Female Impersonators opened in New Orleans, a strip club populated with transgender women who danced and served drinks to visiting patrons. Some guests discreetly slipped through the back doors, others openly enjoyed the company, a handful came just to gawk in disbelief at what they saw. “Usually when people talk about trans people, they think that, you know, we just got here, back in the ’80s,” Isham says. “They center on really big cities, like New York or L.A. or London. The idea is that you have to move to [one of them] in order to develop. This is not that.”

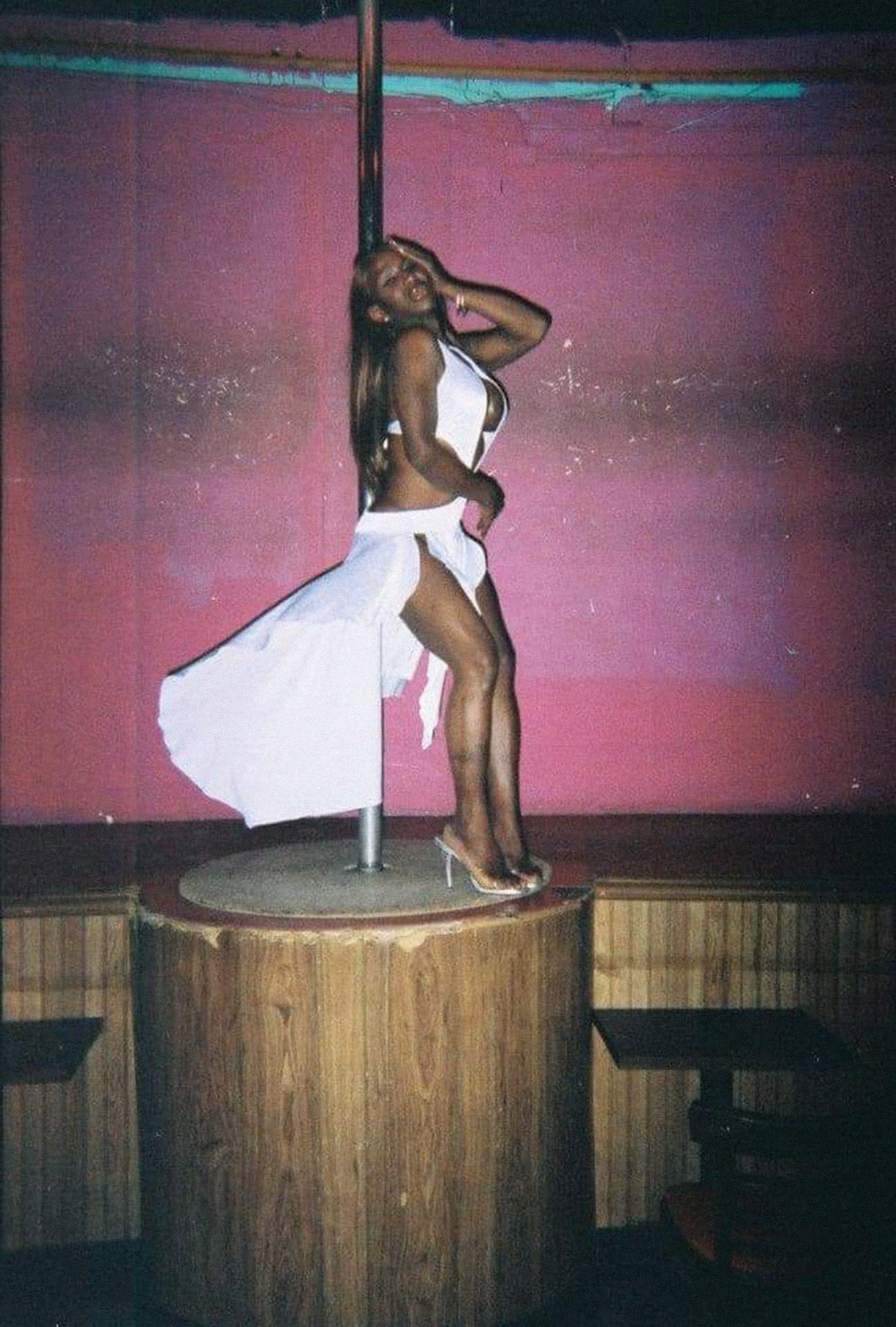

Papa Joe’s, though brash and exciting, provided the opportunity for trans women in New Orleans to make money in a working world that traditionally shunned them. It was imperfect – as Isham tells us – but one of the rare careers at the time that gave these women both creative and financial autonomy.

Originally a documentary, Isham’s project on Papa Joe’s has since expanded into different mediums, making use of her familiarity with sound and performance, with the intention of creating what she calls ‘performance lectures’. “I don’t want it to be super didactic,” she says. There’s also the issue of creating a place for the scarce information surrounding the club to live. “I’m making this film, but I also want to build the scholarship of Papa Joe’s, and create a digital archive crediting the women.” Before Isham started talking about it, “Papa Joe’s [was] not on the internet at all.”

Here, Isham tells i-D, in her own words, a brief history of the mystery and magic of Papa Joe’s Female Impersonators.

“Papa Joe’s has been a ghost in my background my entire life. I call the women from Papa Joe’s that I speak to my ambassadors. I discovered one of my ambassadors, Kineen Mafa, on YouTube when I was in high school. At that time there weren’t many trans people on YouTube. She was a woman with a full, complex story beyond her gender. Kineen was very spiritual and is a theologian. She had already transitioned at that time. It was good for me to see that.

In 2018, at a storytelling workshop for the Center of Black Trans Women, I actually got to meet Kineen in person. The majority of the people there were much older than I was. I’d heard them talk about so many different things, but one of the things that intrigued me was Papa Joe’s. They knew that I was in film and doing composition, so they put that bug in my ear to do something. I just needed a little bit more time to learn what I was doing.

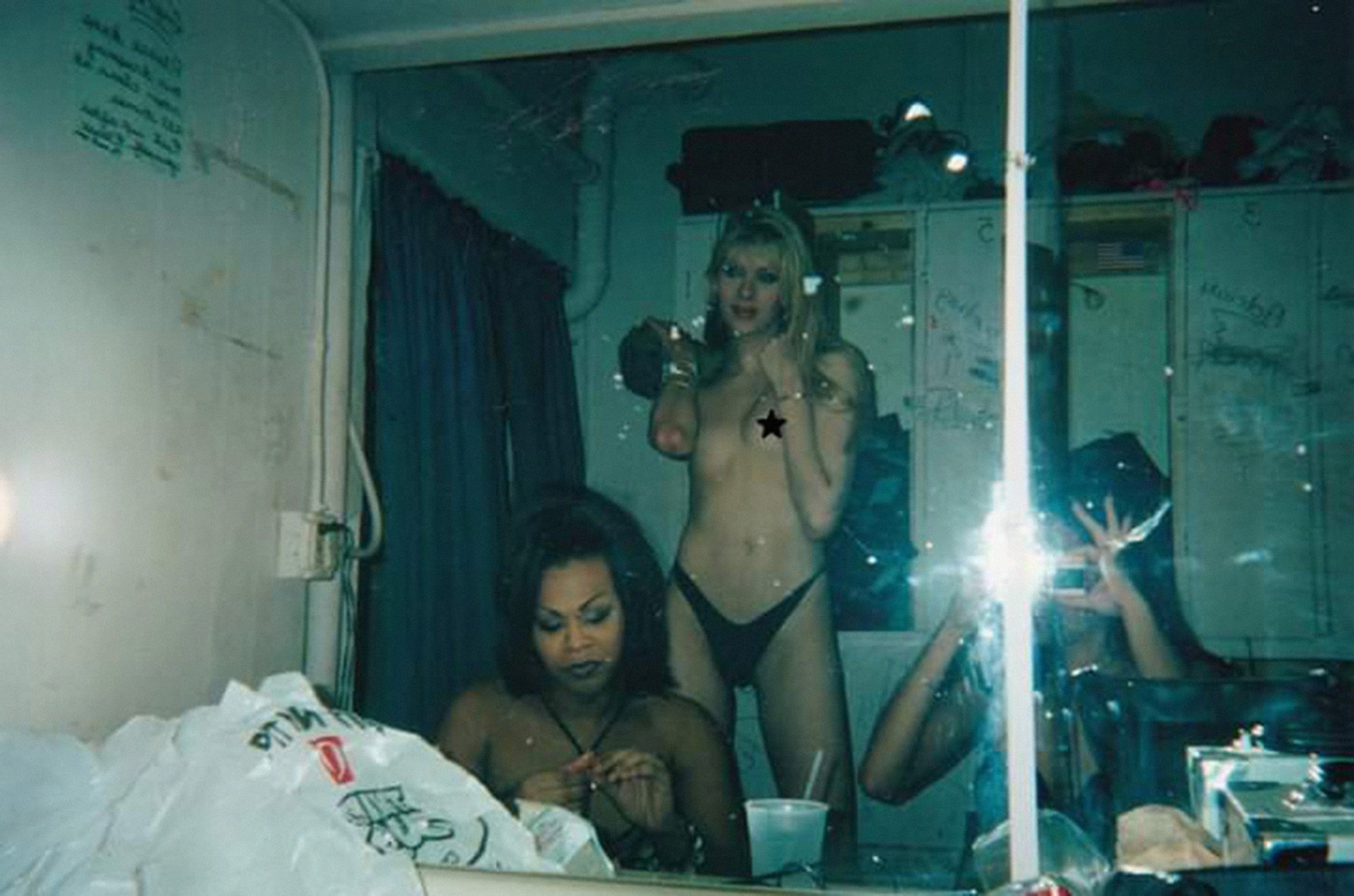

A year ago, I was with two sisters of mine, two other trans women both from New Orleans, and we went to a performance literally across the street from my apartment where three of the girls that worked at Papa Joe’s were performing. I have three ambassadors: Jasmine White, Kyra Auzenne and Kineen Mafa. And I knew Jasmine and Kineen before. It was just the four of us in the dressing room, Jasmine and Kineen had already talked about doing some work with the project. I told Kyra about this idea, and she immediately loved it. She said: ‘Come to church with me’.

When you Google the club, nothing at all comes up.

Now, I’m a Buddhist. The thing I’m talking about in this project that I’ve never seen in other projects is the connection to spirituality. New Orleans is a very complicated place. It’s a very Catholic city, but it’s also witchy and voodoo and all that kind of stuff. These things that seemingly are in opposition to each other are, in New Orleans, in a deep relationship with each other. Meeting transsexual Catholic strippers is not unusual. So I went to church with them, and what was so interesting about that experience was that everyone at that church was a trans woman. There was one woman who wasn’t – and her son, who was gay, was the pastor. After that, we had dinner, we did some recording and talked more about the project. That’s how it kind of started.

After that, I officially started to work on filming, interviewing and diving into the little bits [of information] that I could find. The youngest people that were at Papa Joe’s are now in their late 40s, and the oldest living ones are, like, 81. Many are deceased. When you Google the club, nothing at all comes up.

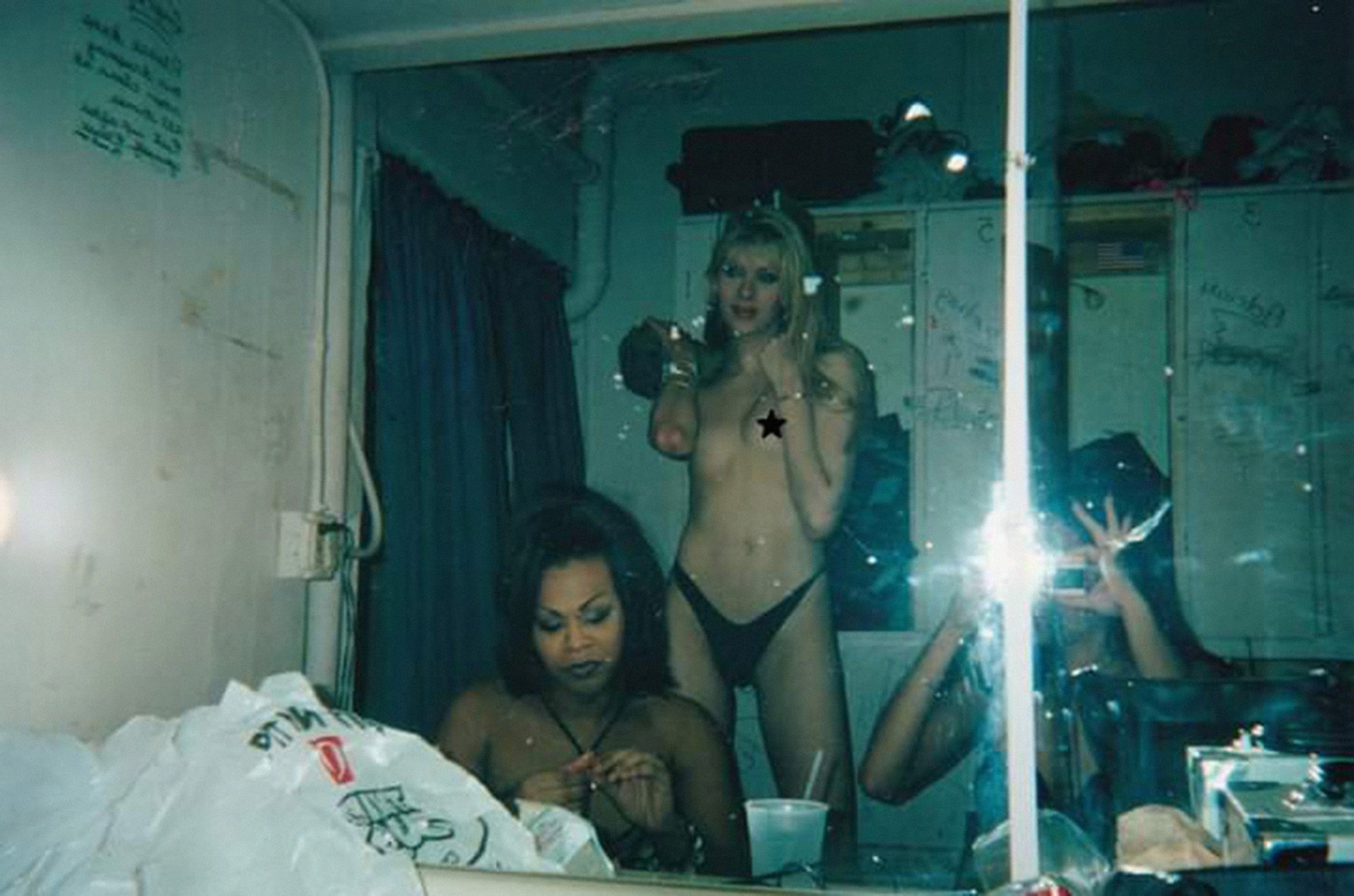

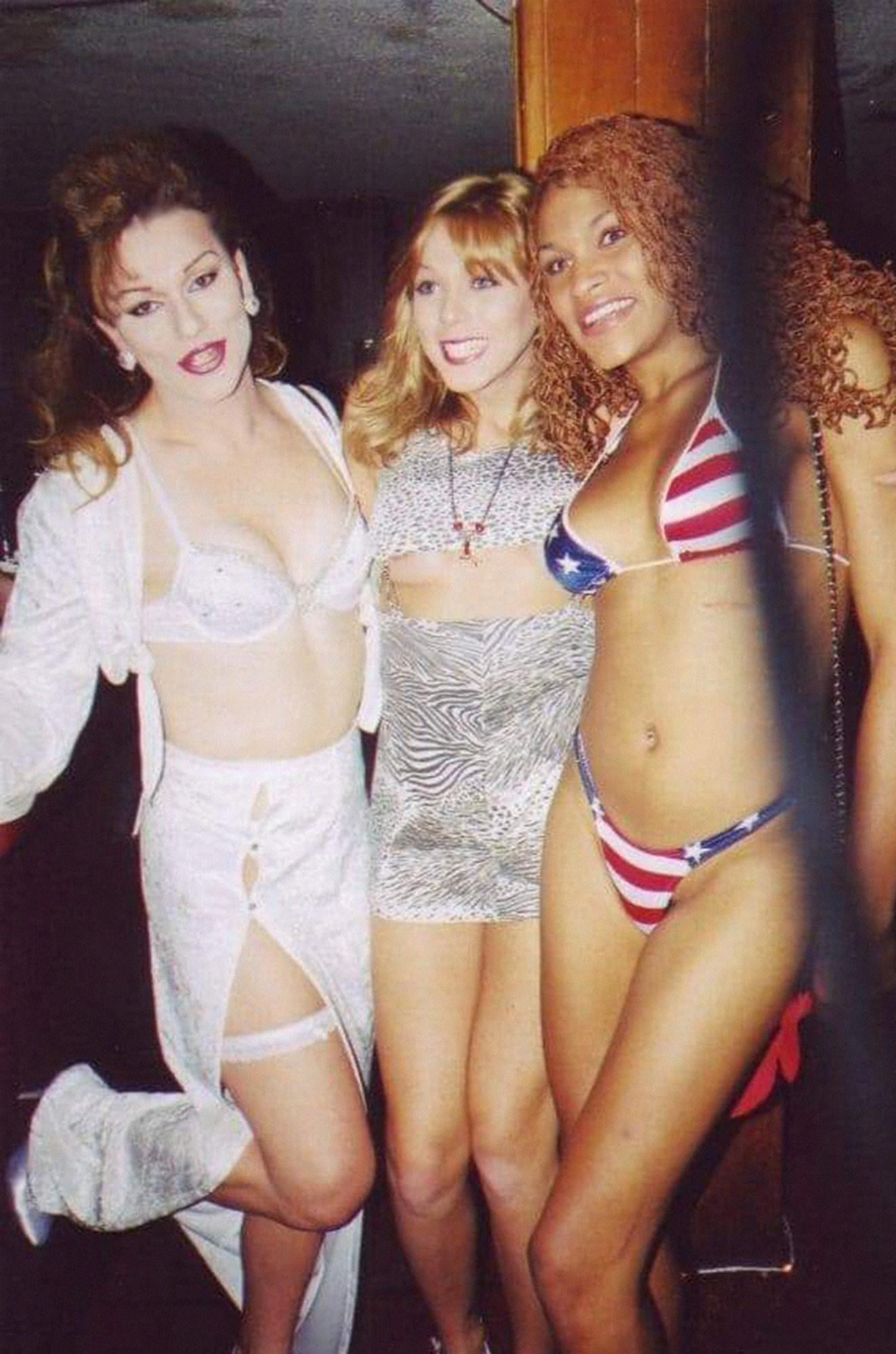

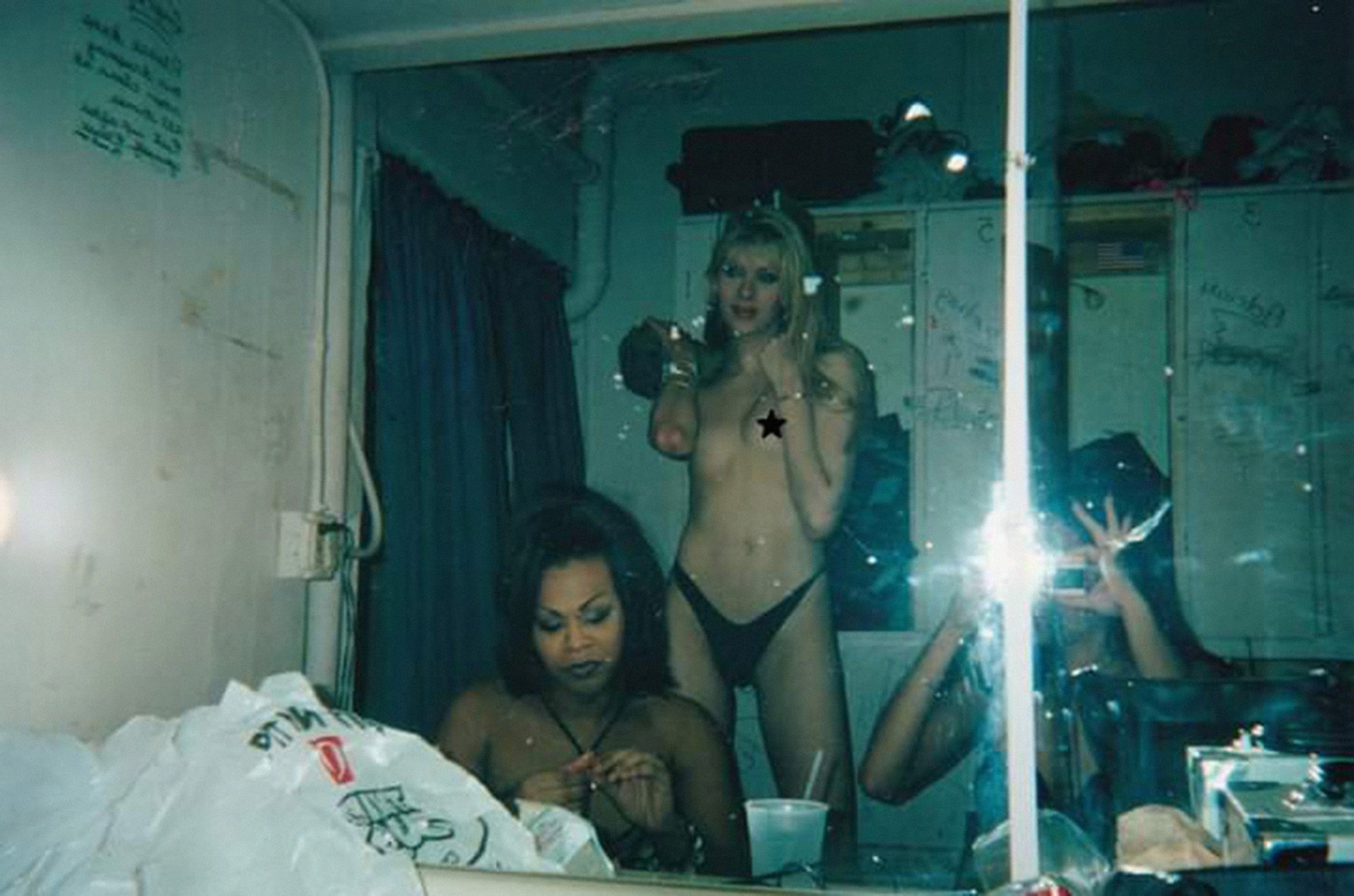

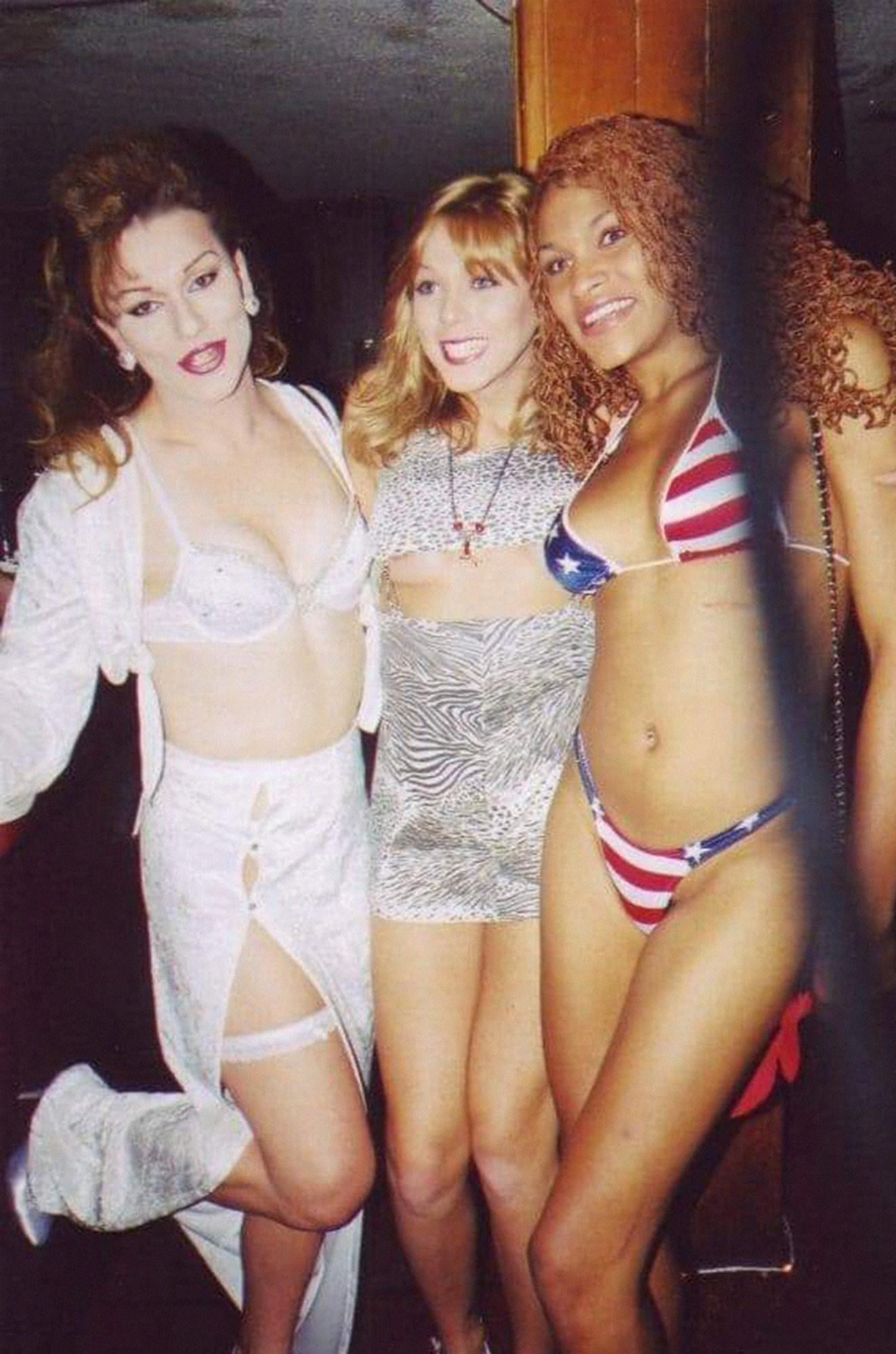

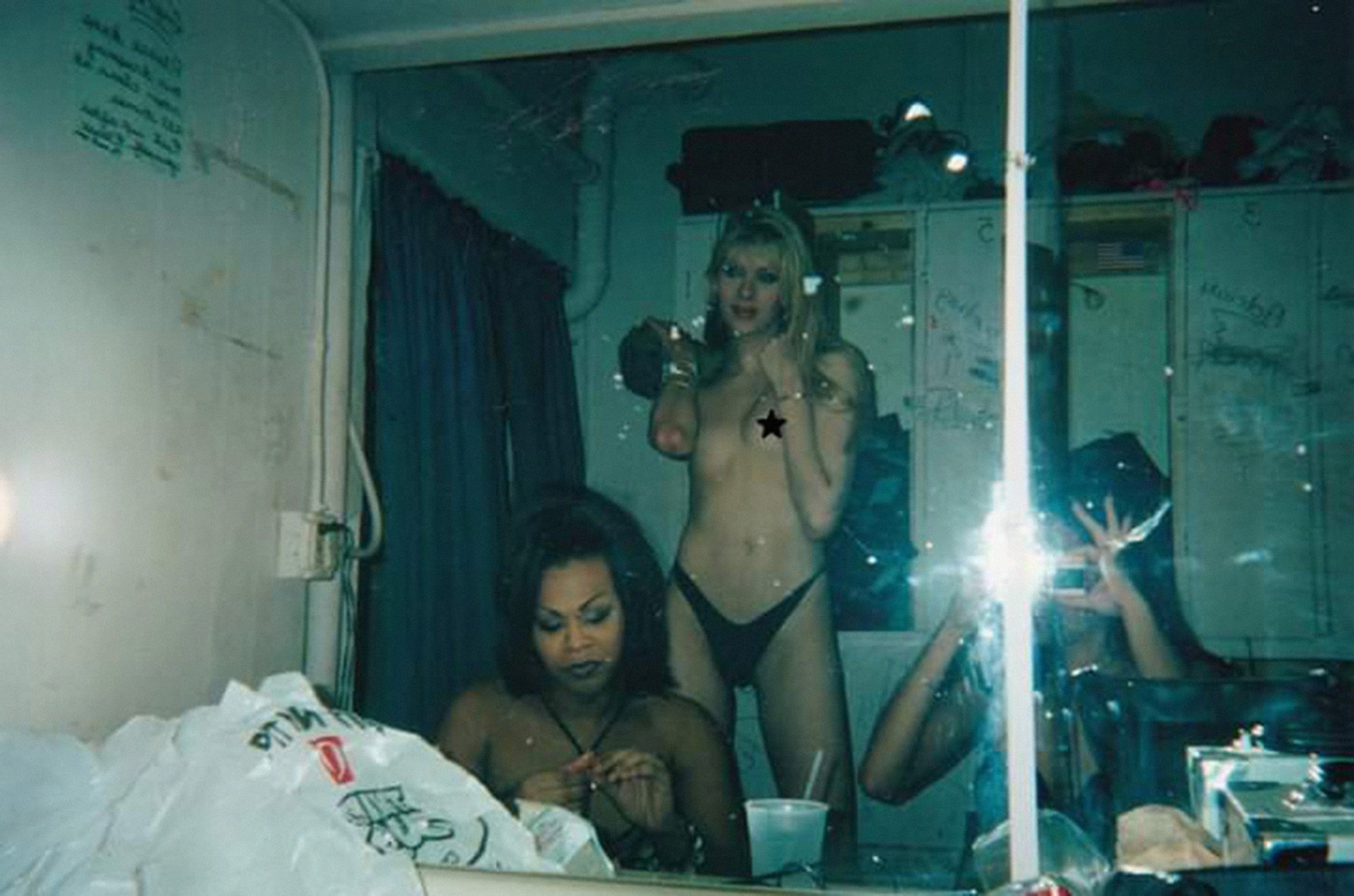

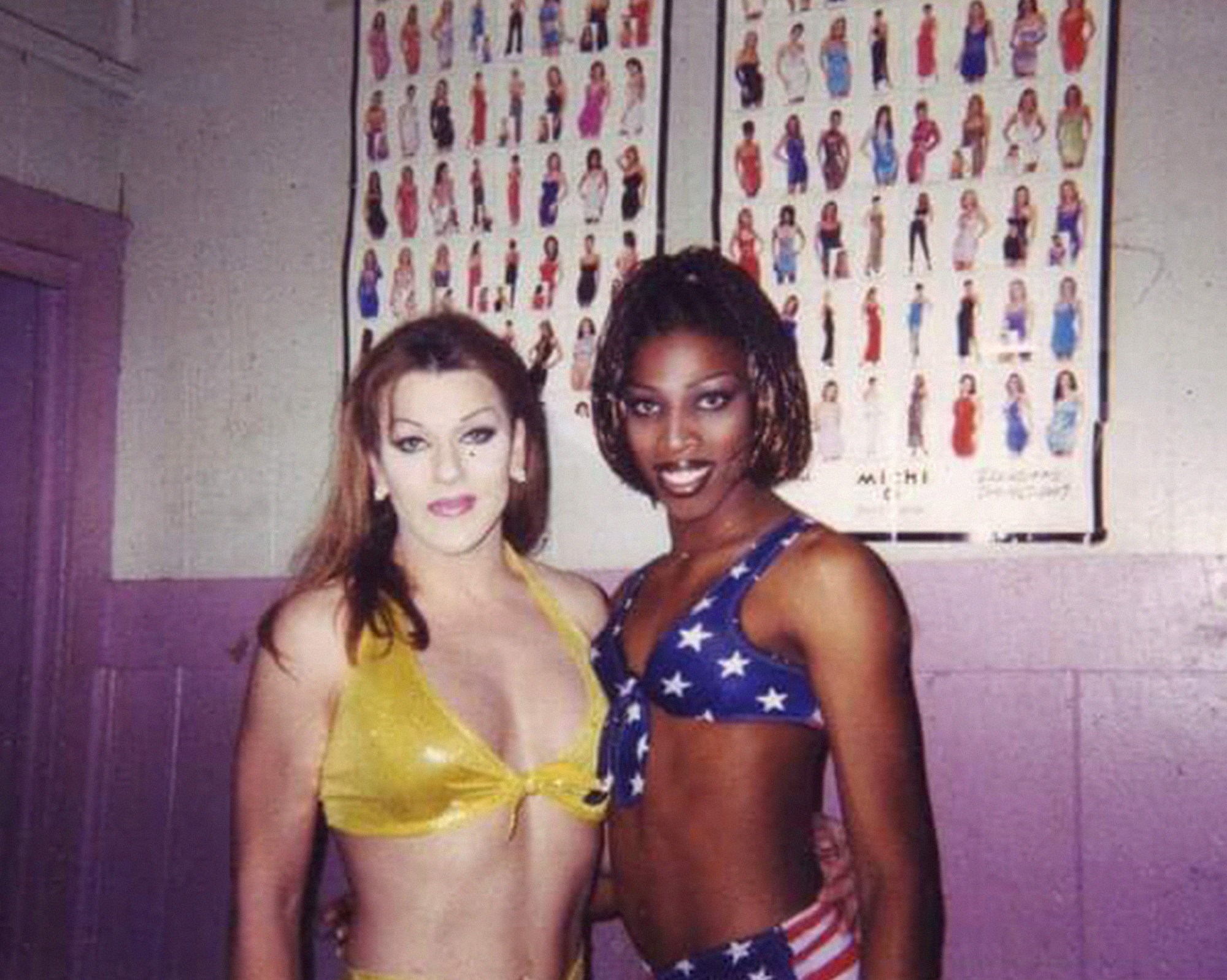

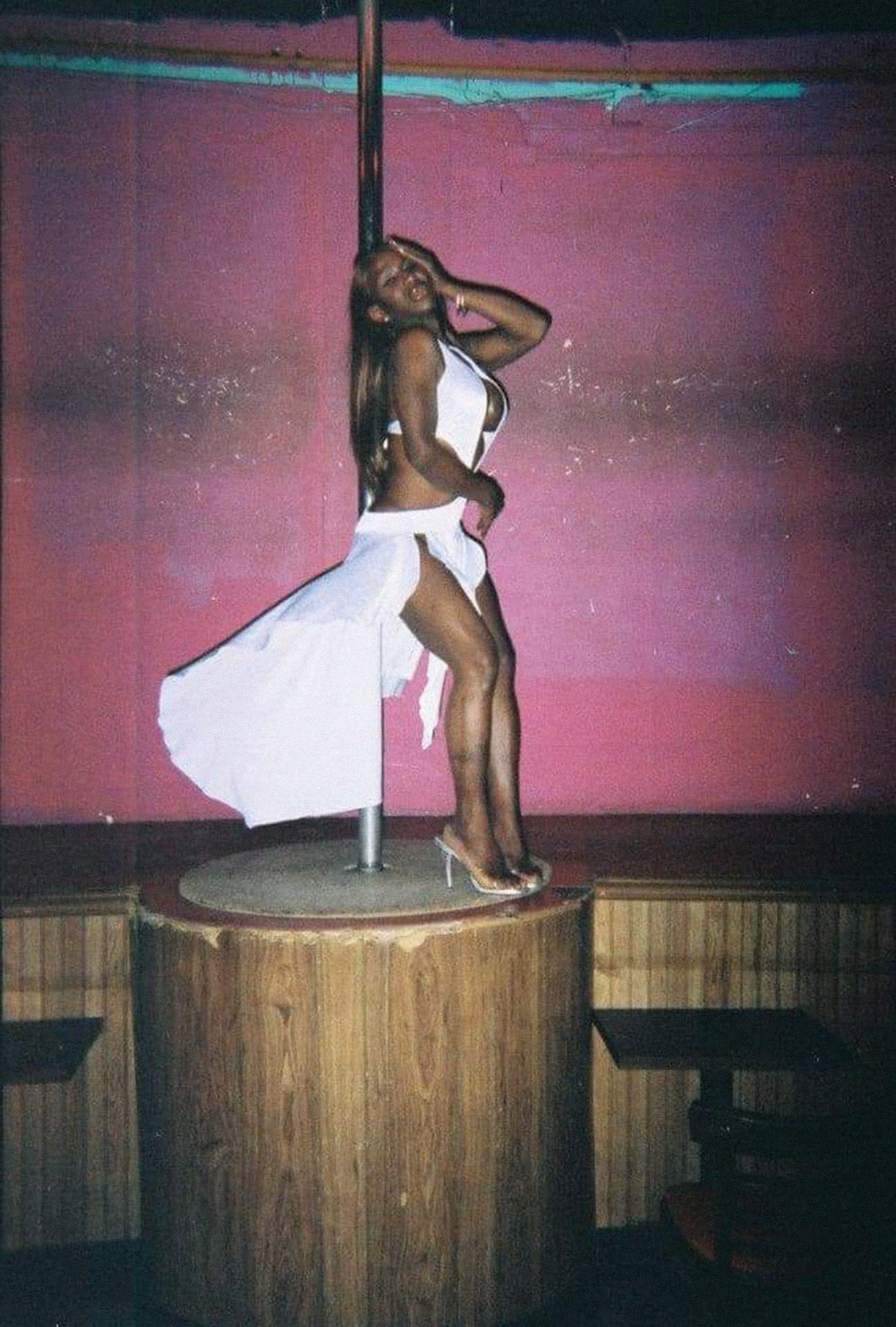

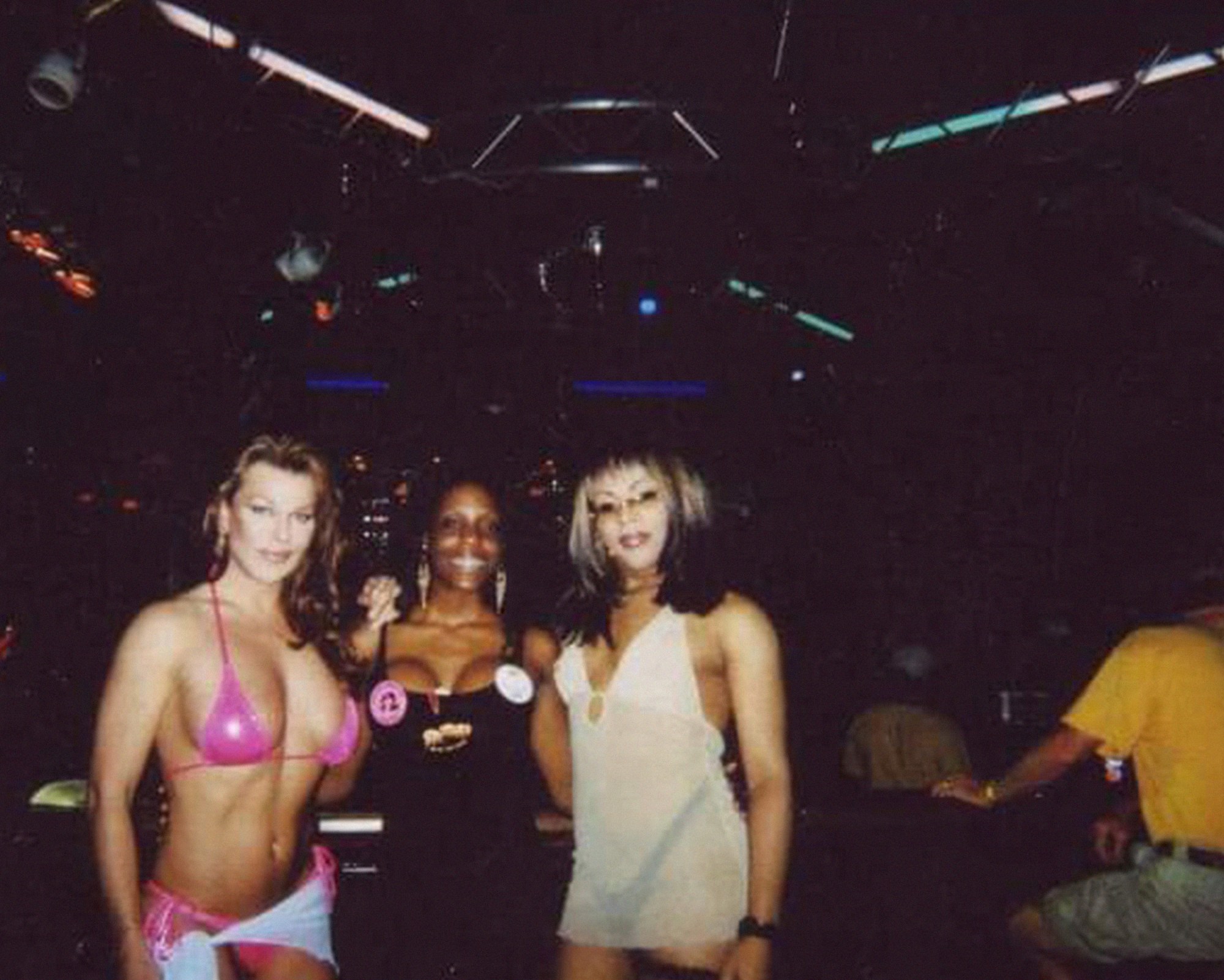

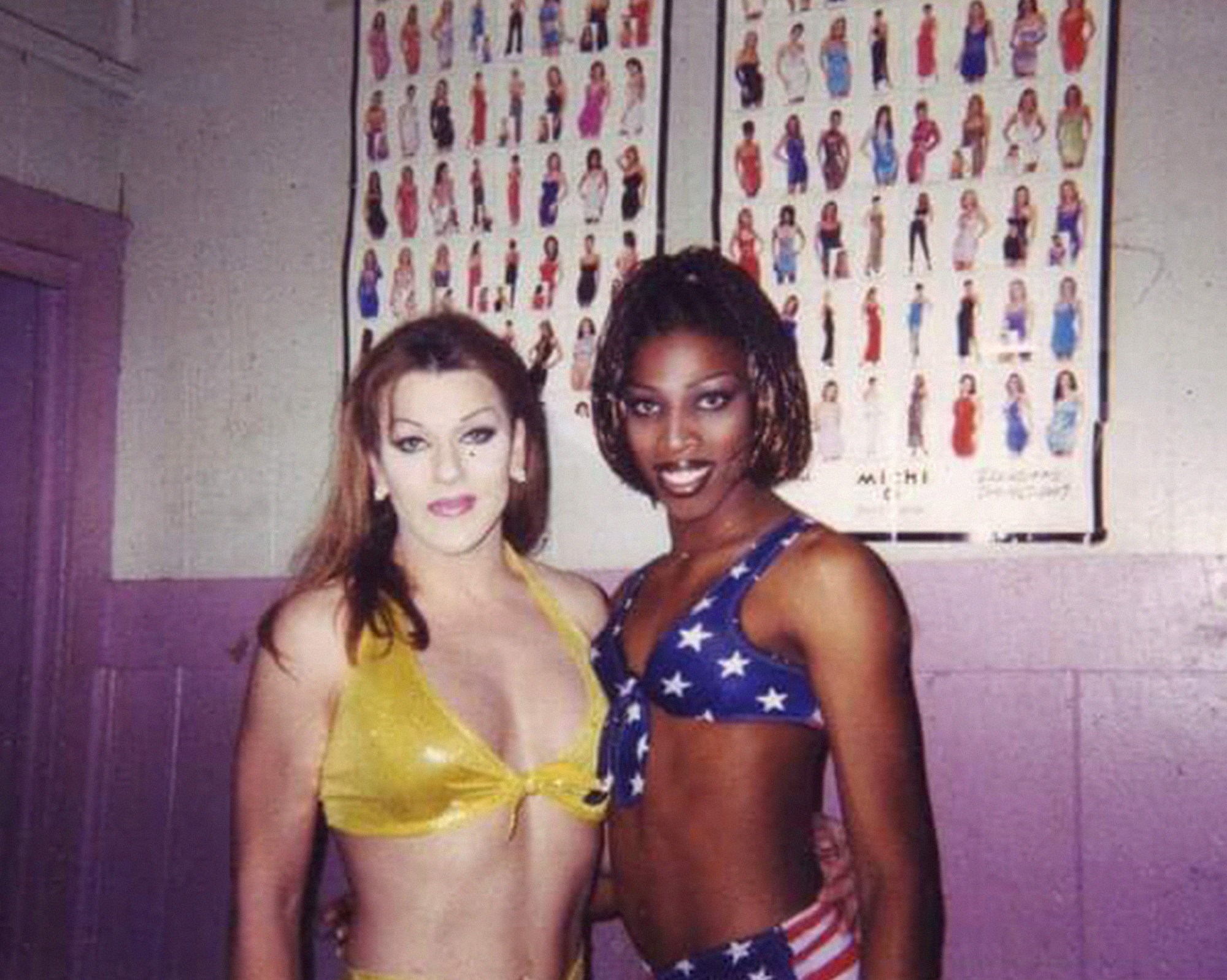

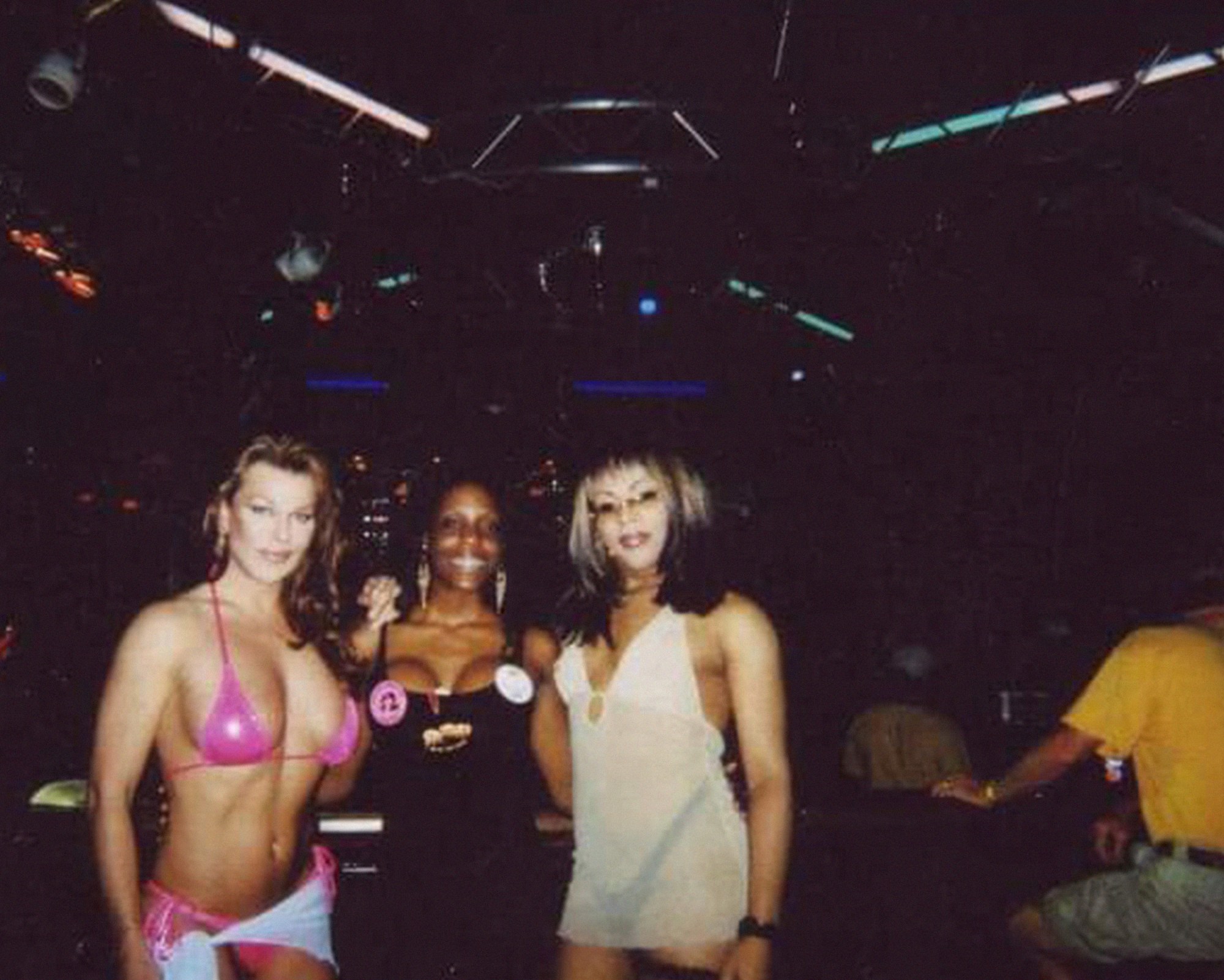

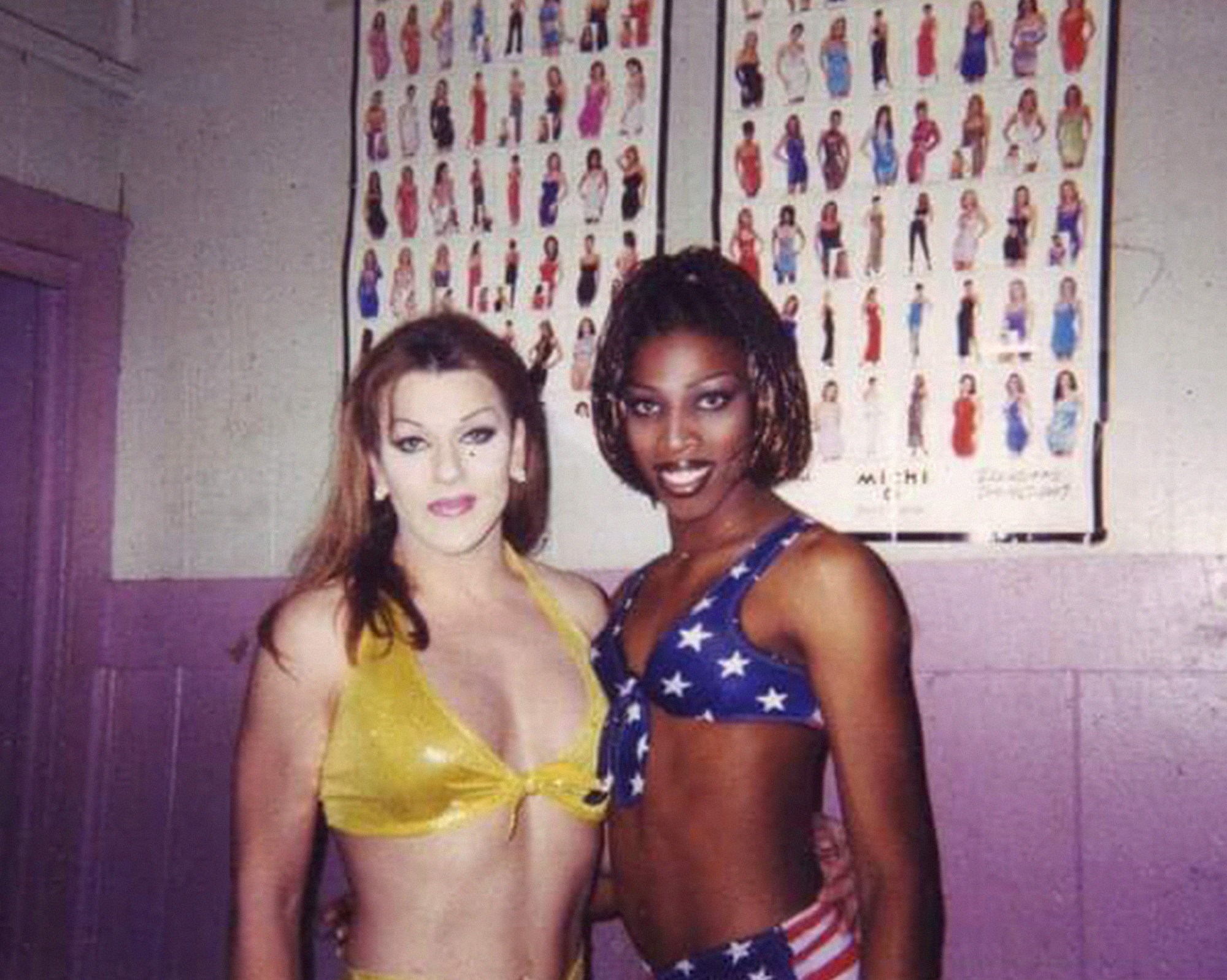

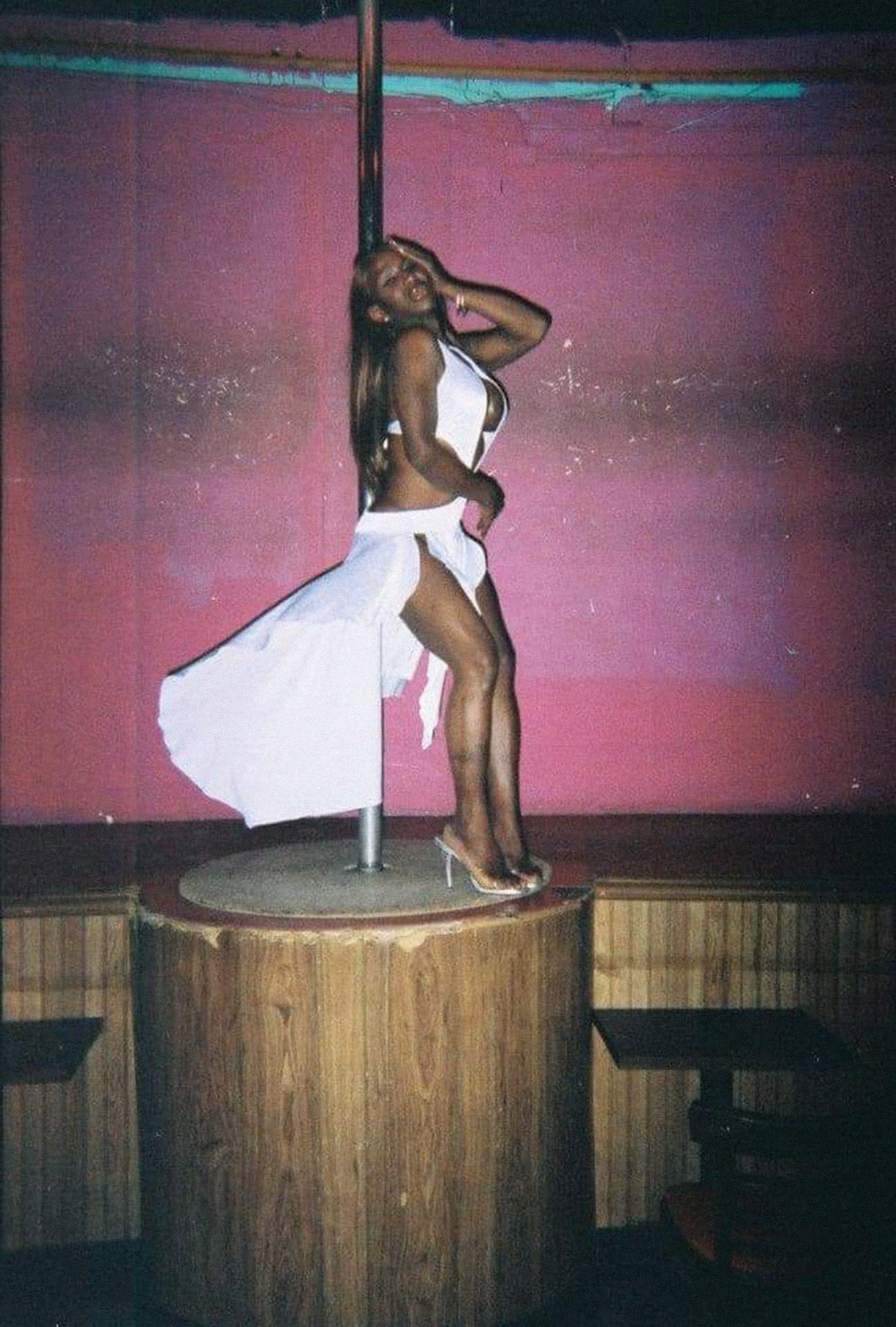

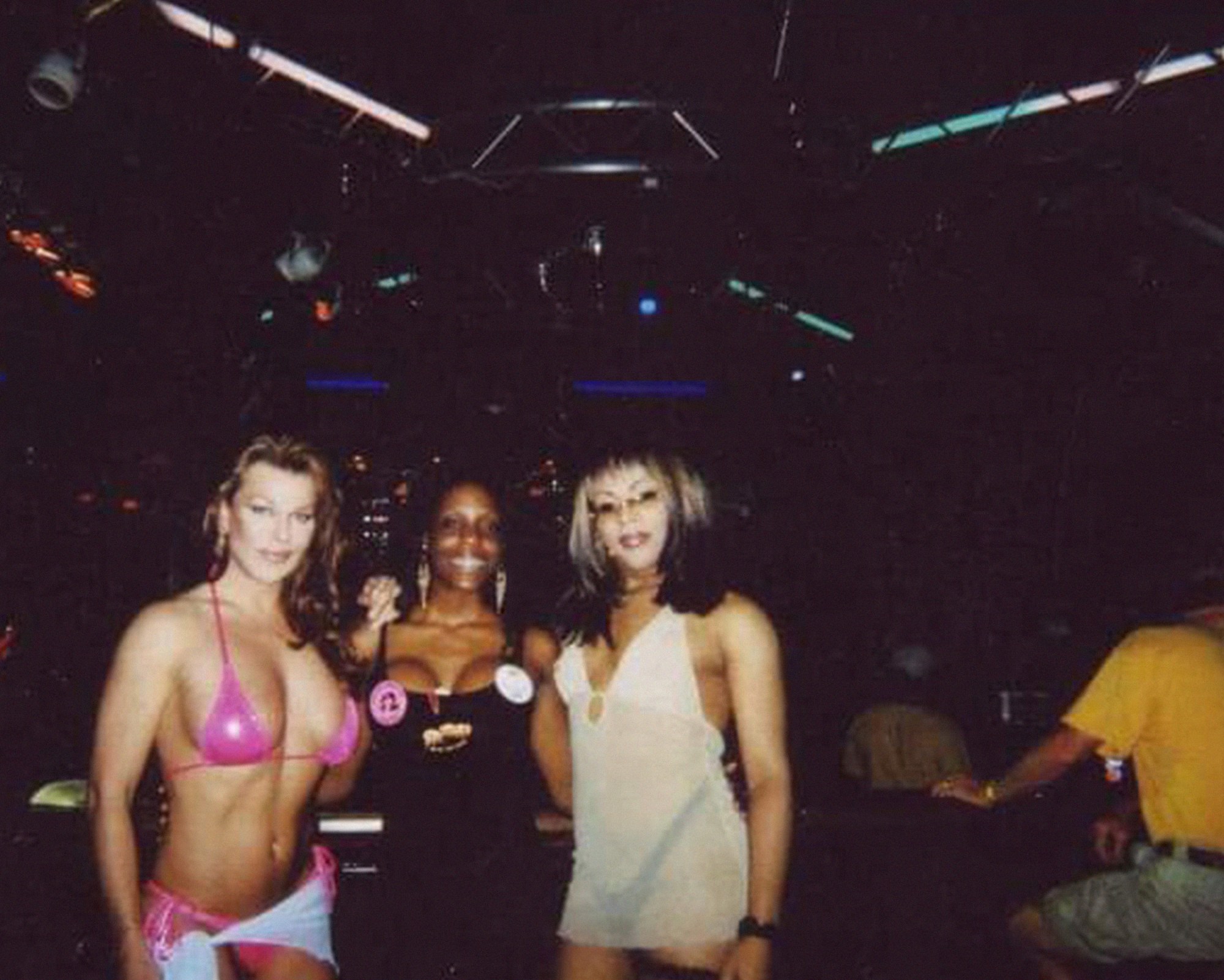

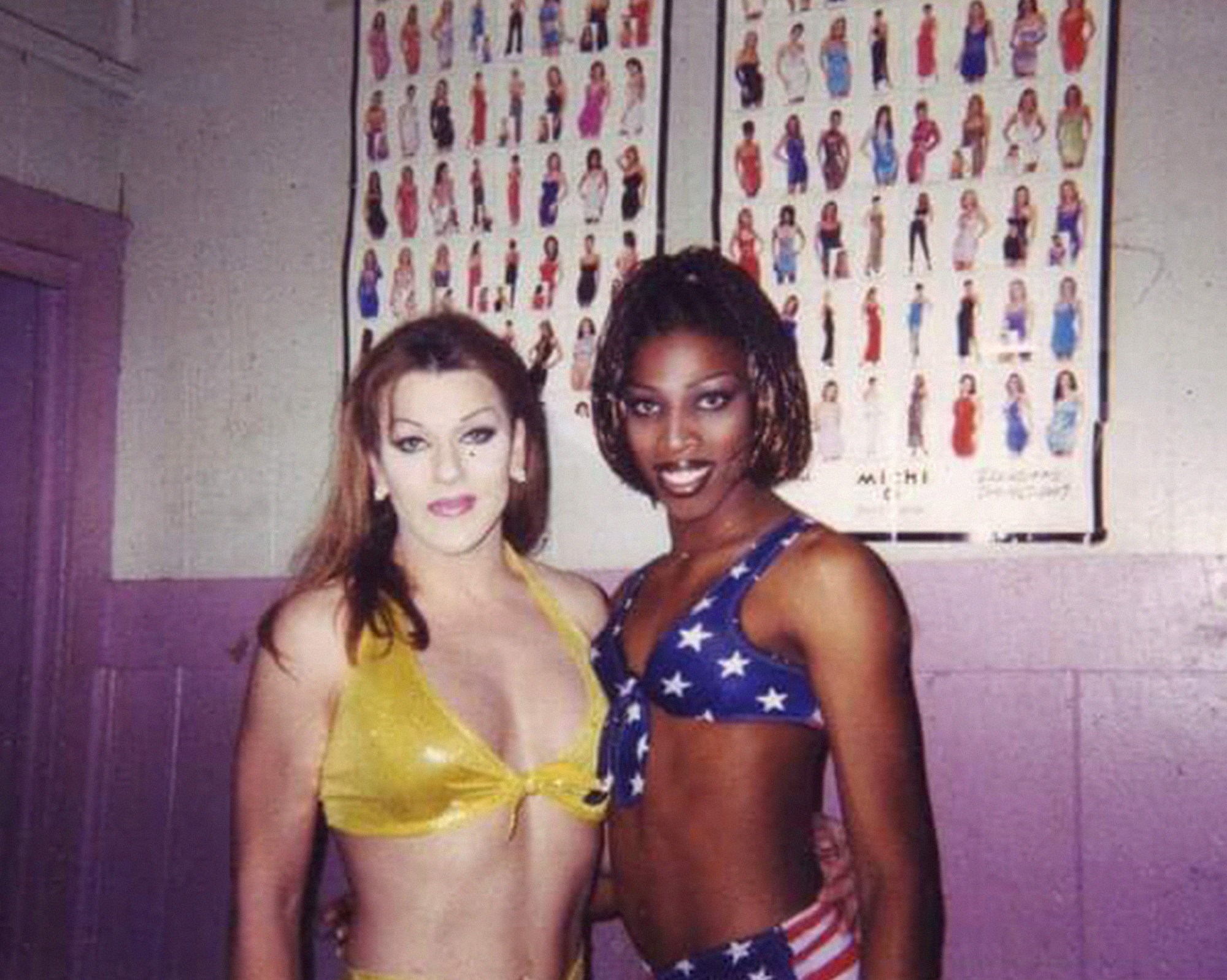

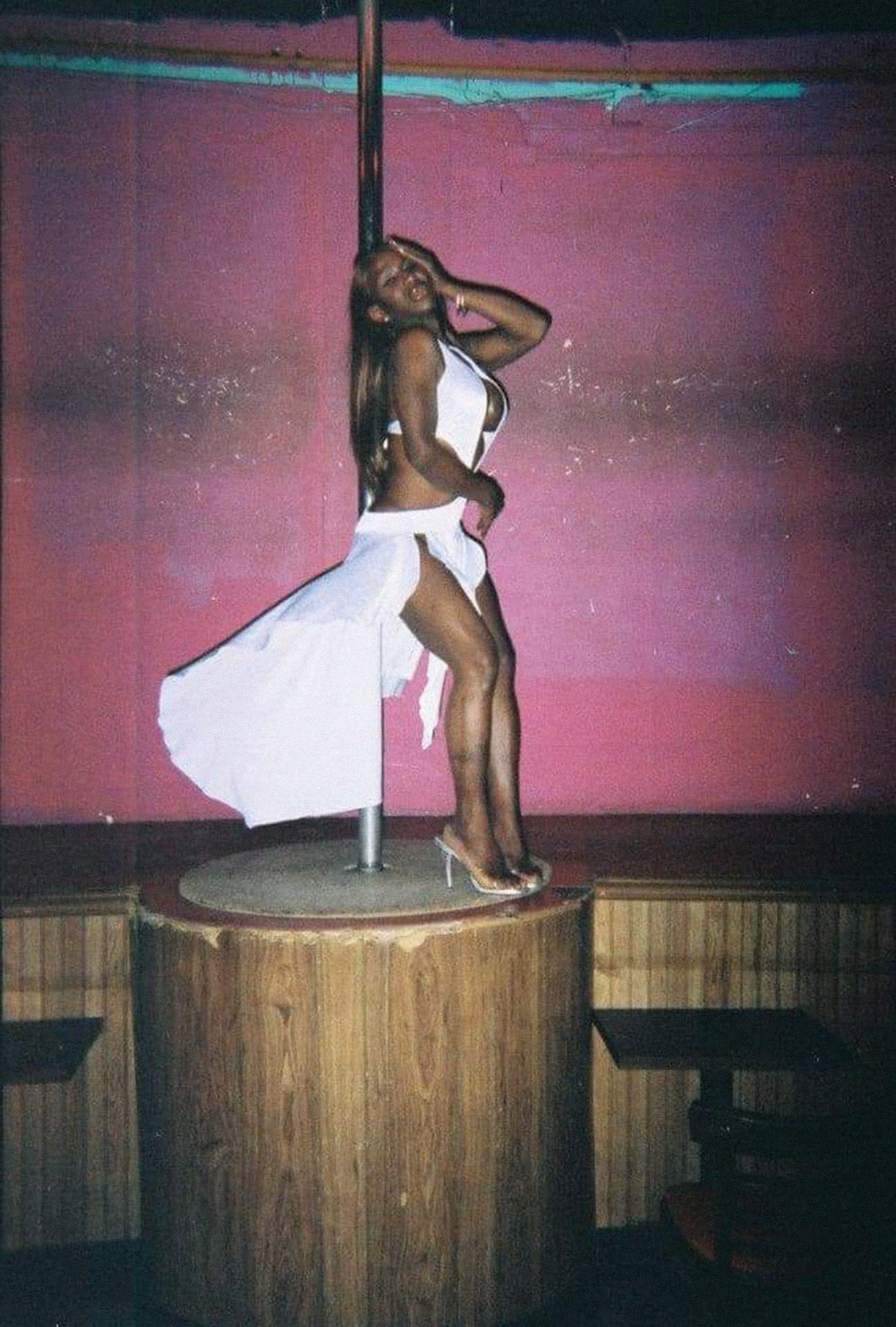

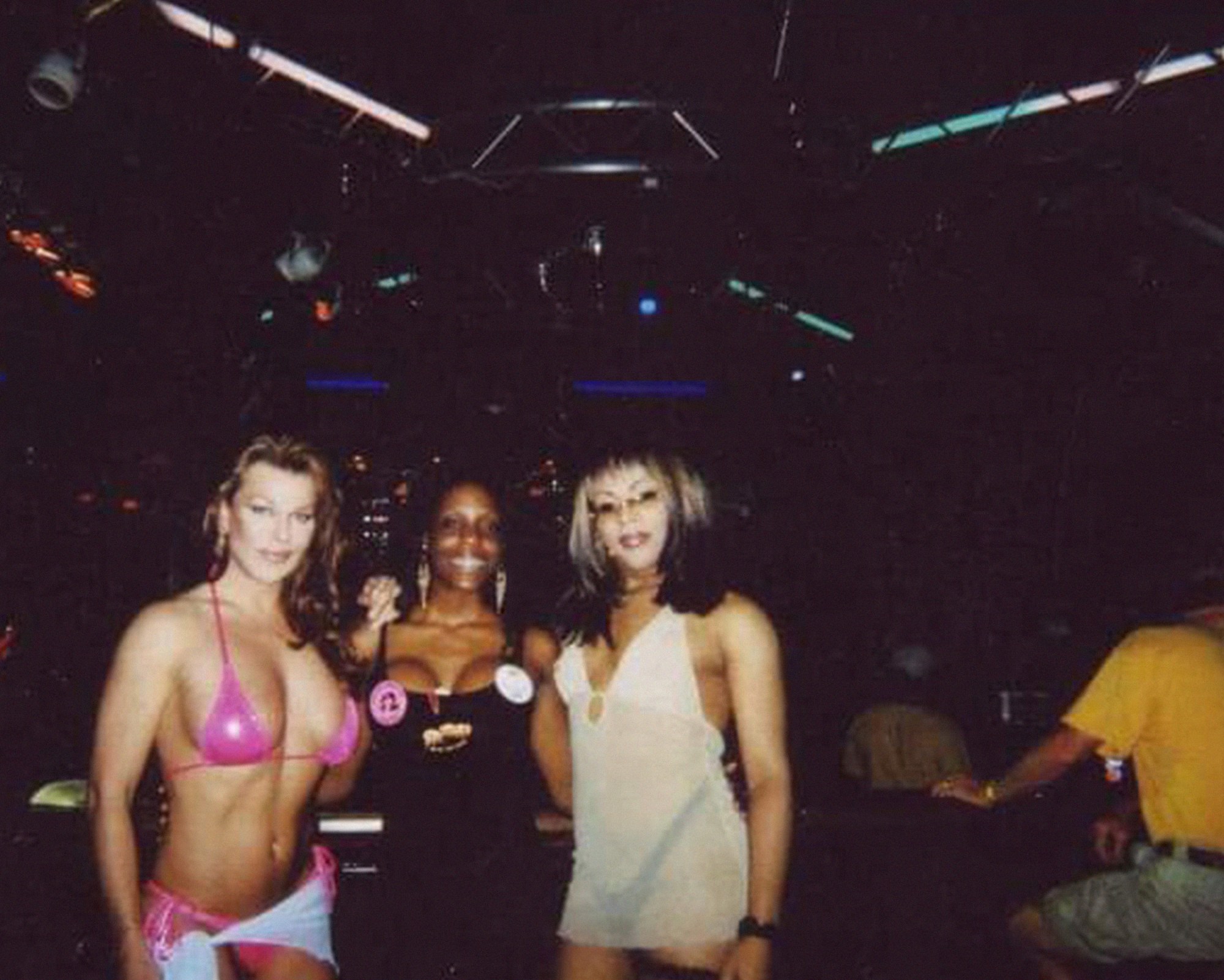

All of the photos that I have were shared with me by them. There’s a Facebook group, and I’m the only person in the group that’s never been a Papa Joe’s girl. They gave me all of these beautiful images.

The girls told me that the original owner was actually from Italy, and he moved to New Orleans when he was six years old. The rumour was that he was actually a member of the mob. There were two Papa Joe’s. The first one started in the 50s, and was in that spot until the late 90s, then they moved a block away. The girls talked about [the original Papa Joe’s] like it was the good old days. They made more money there, and I think that was because the entrance was not at the front of the street, so people were able to be discreet.

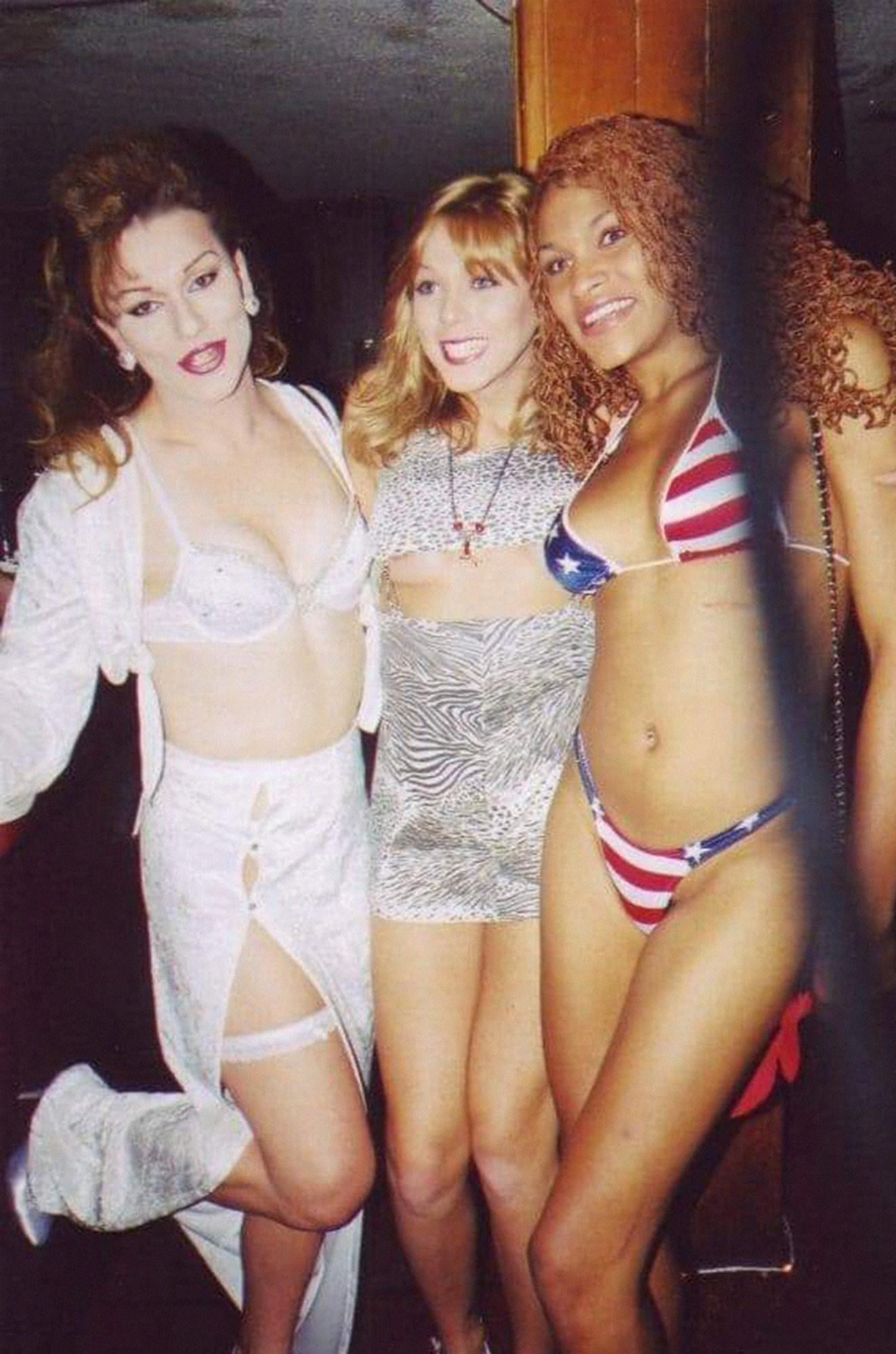

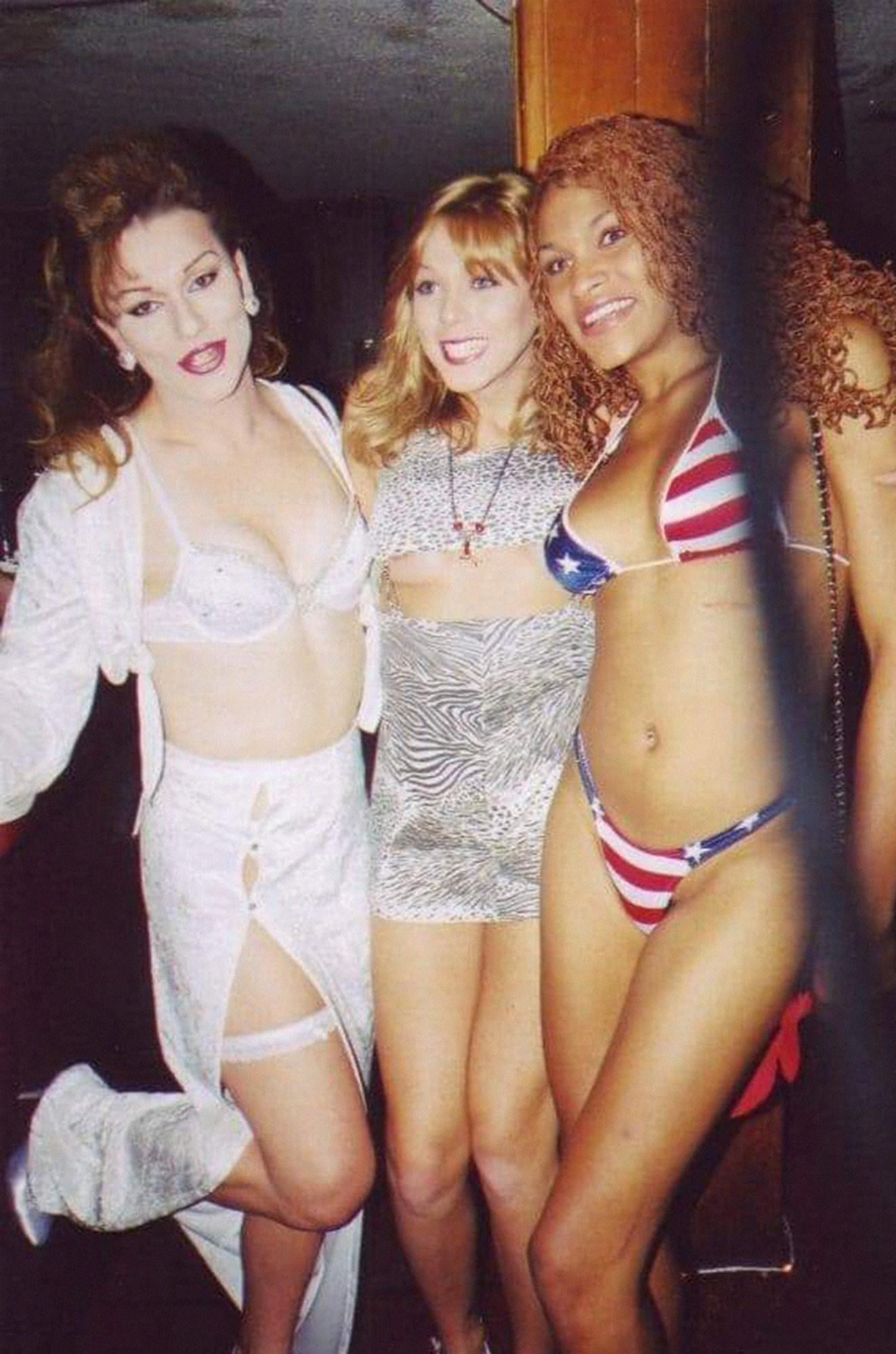

An older group of girls, who I think are probably all white, have their own group. That’s part of the complicated nature of this project: the intergenerational relationship between trans women of this age; a story of segregation.

Papa Joe’s Female Impersonators was historically only for white trans women. It started in the ’50s and was exclusively white. I think in the ’60s, they started to sprinkle one or two [non-white dancers] in, but they were never the feature. As a feature, you were never fired. You could work whenever you want. You could stop a girl’s routine and the middle of it and take up the stage. A lot of those girls were [in demand] all over the world, so they would be traveling. They wouldn’t really be there a lot. So the other girls were the ones that were really making the club sustainable and afloat and alive. When they started to incorporate more Creole or Black or Latino women, they would only have one at a time. By the early 2000s, they describe it as being mostly Black and brown women.

People could summon a trans woman from the internet, so they didn’t have to go out to the club.

LaWanda was the first and only Black woman to have ever been a feature, and that wasn’t until the 90s. Everybody loved LaWanda. Everyone speaks of her with high regard. She would call out the bullshit and still be friendly and genuine and defend girls who might be having a tough time. The girls described her as a comet: there for a short time, but made a big impact.

Whenever a war would come, the sailors would head to Papa Joe’s. Before going off to the [Iraq] war after 9/11, they said it was packed. They wanted to experience seeing one of the girls before possibly dying. Members of royal families also came, as did celebrities, government figures, talk show hosts… Jerry Springer used to come down.

I’m saying transsexual: I wanted to use that language. We don’t have a problem with it. With the term ‘female impersonator’, [you had to use it] to work at popular spots. You had to degrade yourself. You [were expected] to be grateful, and say things that you don’t feel about yourself. Even the name of the club. None of the girls liked it, but there is still clarity within that language. All female impersonators can do drag if they wanted to, but not all drag artists can do female impersonation, because the whole point of female impersonation was for people to not be immediately aware that this person was assigned male at birth. It’s not campy. It’s not dramatic in that way that drag is.

When they went to the second Papa Joe’s location, that’s when they’d say the good times were over. We were starting to get chat rooms and Backpage. People could summon a trans woman from the internet, so they didn’t have to go out to the club.

[The former Papa Joe’s dancers] all do different things now. A few work in health care; others are independent artists. Some married men and kept quiet. They don’t want to talk about those days. Many went to college. A lot of them felt like Papa Joe’s was college for them anyway.”