The trouble with reverence arriving after an artist dies is that we can’t retroactively fill in the gaps of their life in their own words. Being told you are an icon means your life is pored over constantly, each moment saved by someone – if not yourself – in scrupulous detail. We know exactly who they are because people cared enough to help preserve that memory.

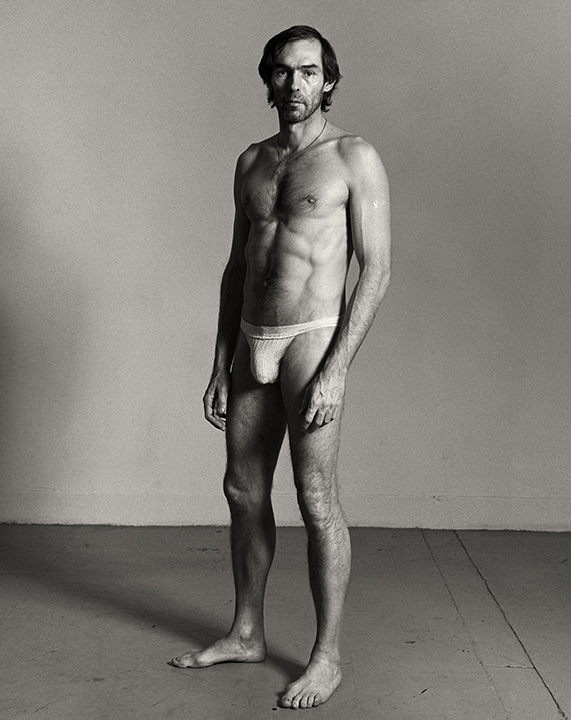

After photographer Peter Hujar died of AIDS complications, aged just 53 in 1987, he became more famous than he had ever been alive. During the ’70s and ’80s, a golden age of queer American photography, Hujar’s work had been overshadowed by his contemporaries, notably the boundary-pushing Robert Mapplethorpe. Mapplethorpe and Hujar are considered artistic bedfellows, intertwined by their shared embracing of sex, bodies and enrapturing portraiture – shot in black-and-white.

While Mapplethorpe released nearly a dozen monographs in his career, Hujar made just one: 1976’s Portraits in Life and Death, a stark selection of images of his friends on New York’s Lower East Side (Divine, John Waters, Candy Darling, Fran Leibowitz) and embalmed bodies, skulls and tombs in the Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo. The foreword came courtesy of Susan Sontag, who wrote her introduction in 40 minutes from a hospital bed, having been recently diagnosed with breast cancer. But when it was released, he was disappointed by its reception, and of the quality of the finished product. Though Hujar’s work was no less provocative, the camera lens and the dictaphone swung Mapplethorpe’s way in the time they shared a creative space. People cared less about what Hujar said until it was too late to ask him any more questions.

When one of his more kinetic and expressive portraits, “Orgasmic Man” (1969), graced the cover of the deeply depressing Hanya Yanagihara novel A Little Life in 2014, the novel itself outsized Hujar’s history. Even today, the image’s reappropriation is more recognisable than the man who made it. Still, it laid the groundwork for a tide turn towards what Hujar made. According to many of his friends, in 2018, when an exhibition of his work titled Speed of Life ran at New York’s Morgan Library & Museum, that was solidified: all of a sudden, a penniless photographer the art cognoscenti broadly ignored became lauded as a great.

It’s spiralled upwards since then: at the Venice Biennale in 2024, 41 images of Portraits in Life and Death appeared for the first time in their entirety in Europe. After being out of print for decades, the monograph itself was reprinted by Norton and Co in October last year. Copies of the original had become a rarity, with some retailing for nearly £1000 on the second hand market.

Later this month, Raven Row in London will play host to Peter Hujar – Eyes Open in the Dark, the first posthumous exhibition to have access to Hujar’s entire oeuvre, and the most comprehensive presentation of his work in the UK. It’s been curated by Raven Row’s director Alex Sainsbury, Hujar’s biographer John Douglas Millar, and Hujar’s close friend, the artist and master printer Gary Schneider. (Millar’s biography is due to be published in 2029.) Then, after its debut at the Sundance Film Festival, Peter Hujar’s Day, a new film directed by Passages’ Ira Sachs, starring Ben Whishaw as Hujar himself, should receive a release in late 2025.

Peter Hujar’s Day is based on a conversation between Hujar and the writer Linda Rosenkrantz, played in the film by Rebecca Hall. The audio was lost, but the transcript was discovered decades later, and was published as a novella in 2022. On the surface, the day he describes feels quotidian for a photographer on assignment, albeit the figures it includes, in retrospect, feel profound and interesting, among them Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs. There are mundane conversations about Chinese food and lovers that unspool with such quiet sophistication and profundity that they sting: this is all we have.

These words, along with a brief, fuzzy audio clip from an interview conducted by David Wojnarowicz – an activist, artist and his former lover – are some of the scant examples of Hujar’s thoughts that have been salvaged from history. There’s a world in which a film adaptation of Rosenkrantz’s novella would have taken liberties with the circumstances Hujar describes, acting out these scenarios, filling in the gaps, in an effort to make something more cinematic and traditional. But Ira Sachs, a filmmaker aware of how little we know about Hujar as fact, studiously honours his words. Shot within the four walls of Rosenkrantz’s apartment, it’s a play-like enactment of their conversations, lustrous and real. It’s a beautiful film about a brilliant artist that sells you on his soul rather than his work.

The film should, in theory, give Peter Hujar another boost in public profile; convince another young photography obsessive to dig more into what he made. Today, his legacy is kept alive by two things: his work and his friends. They have spoken about the bittersweetness of someone so talented and excellent becoming revered only today, when he’s not alive to see it for himself. Perhaps if the right people had cared four decades ago, we’d know more about what went on inside his head. Instead, his photographs – all strange and sad and dangerous – are what’s left for us to lean into.

‘Peter Hujar – Eyes Open in the Dark’ runs at London’s Raven Row from 30 January to 6 April 2025

Credits

Words: Douglas Greenwood

Photography: All images courtesy of The Peter Hujar Archive / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY, DACS London and Pace Gallery (2025), except the final image.