A number of eschatological beliefs predicted the world would end on December 21, 2012 — the last day of the 5,125-year Mayan calendar. In preparation for the apocalypse, survivalists turned to YouTube to learn how to best live off-grid, while conspiracy theorists flocked to the French village of Bugarach to access a mountain thought to be the landing site of a UFO that would rescue them from disaster. In Taipei, art student Pin Chun Kuo was far more accepting of her fate, and settled on photography as the medium for her salvation.

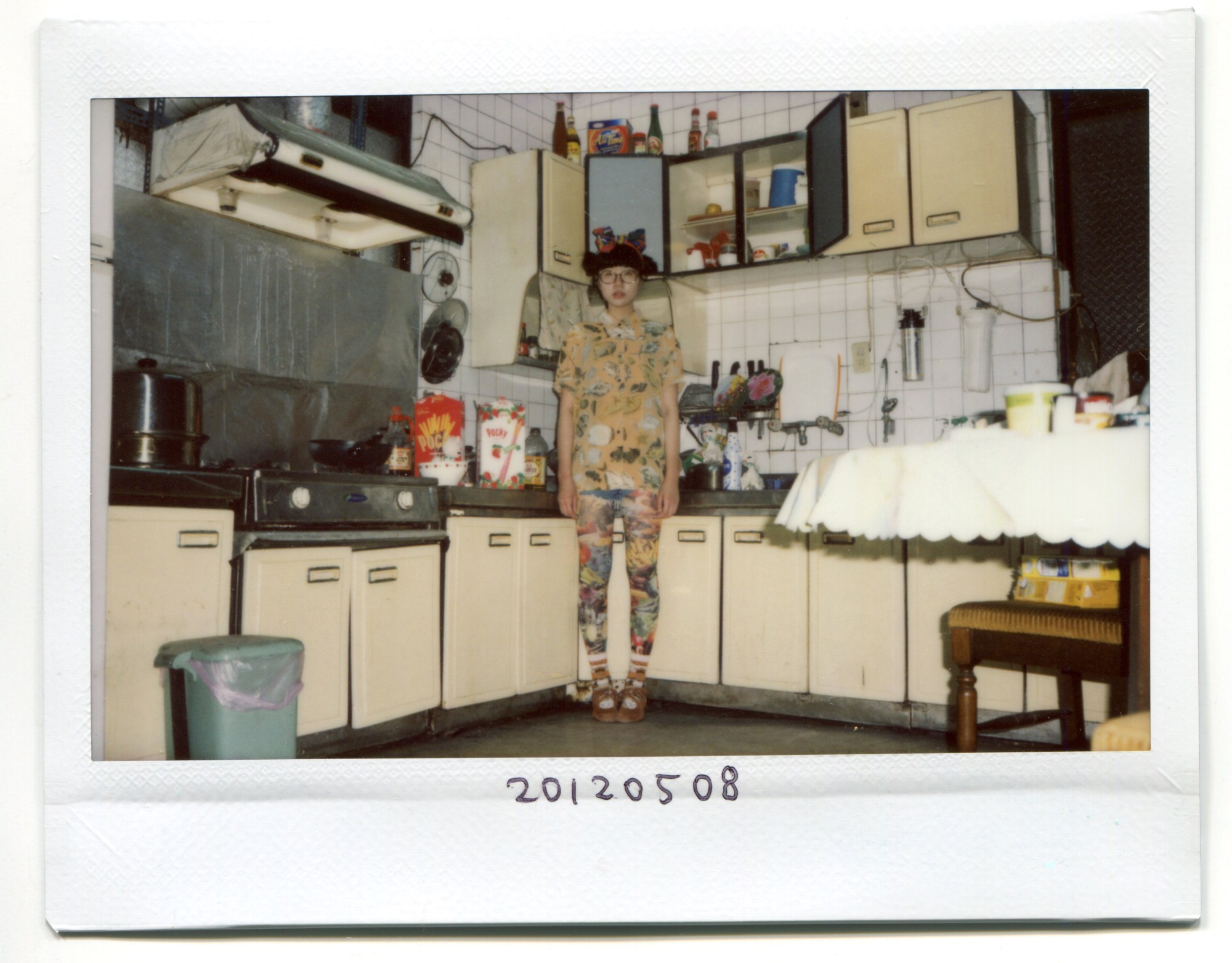

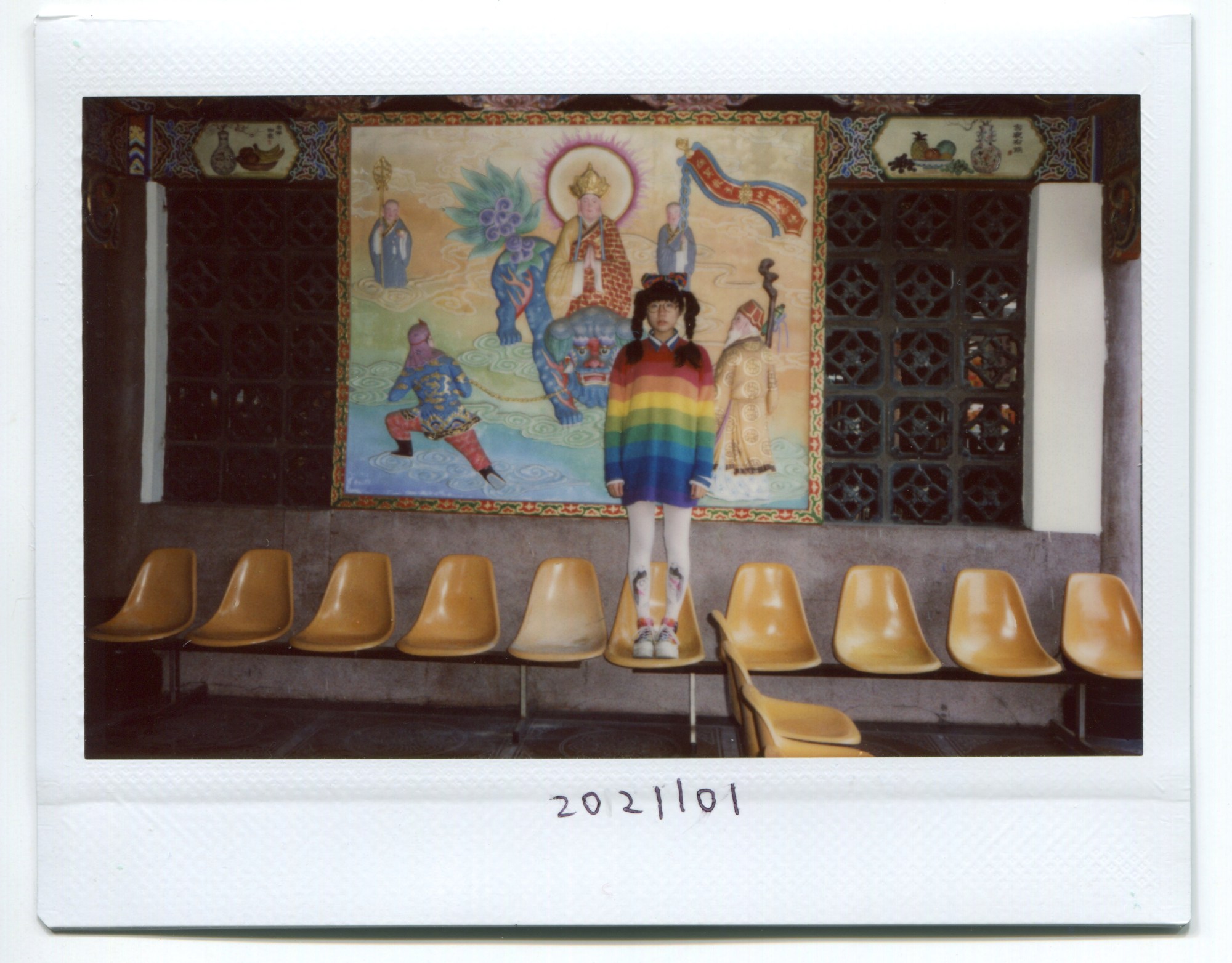

“People kept telling me that artists are never recognized until after they’re dead,” she says. So on January 1, 2012, Pin — an installation artist whose work explores the relationship between pop culture, contemporary society and modern technology — picked up a polaroid camera and took her first self-portrait. It was an ominous shot, lit by the reflective vest of a street cleaner outside Taiwan’s Presidential Office Building, at twilight. For the rest of the year, she took a picture each day, dressed in maximalist costumes to complement the environments she found herself — a pair of fruit and vegetable printed tights for a kitchen portrait, and a rainbow jumper worn outside the graphic walls of the Guandu Temple.

When December came and went without catastrophe (no black hole emerged at the centre of the galaxy nor did the Earth collide with the mythical planet Nibiru), Pin decided to continue the project, “until the real doomsday finally comes or I die,” she says. “As time went by, I have become more and more proficient with the compositions and the colour of the photos.” The series that emerged from all of Pin’s polaroids is as much a personal diary, as it is a sociopolitical commentary on life in Taiwan.

In March 2014, hundreds of student protesters took over Taiwan’s national legislature for three weeks to oppose a proposed free trade agreement with China, which they believed would hurt the country’s economy and leave it open to political pressure from Beijing. Named Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement, after the thousands of sunflowers that were donated to the front lines of the protest by a local florist, the movement joined a wave of youth-led protests across Asia, where activists have fought against repression and brutal crackdowns on civil liberties and human rights.

After joining the crowds that had gathered outside the legislature, Pin began to incorporate politics into her polaroids (her April 10, 2014 self-portrait was taken in front of the armed police deployed to keep the students at bay). Although always with a side of the dark humour she admires in her favourite artists: the French conceptual artist Sophie Calle, and the work of the Tokyo-based art collective Chim Pom, whose multi-disciplinary practice responds to contemporary social issues. “I don’t think I’m an aggressive activist,” she says. “But I care about political issues in my way, using art to deliver messages.” Highlighting issues that are close to her heart, Pin’s portraits are taken in front of signs that advocate for change to Taiwan’s high school curriculum, at election rallies, on fallen advertisements and at a recycling plant for plastic.

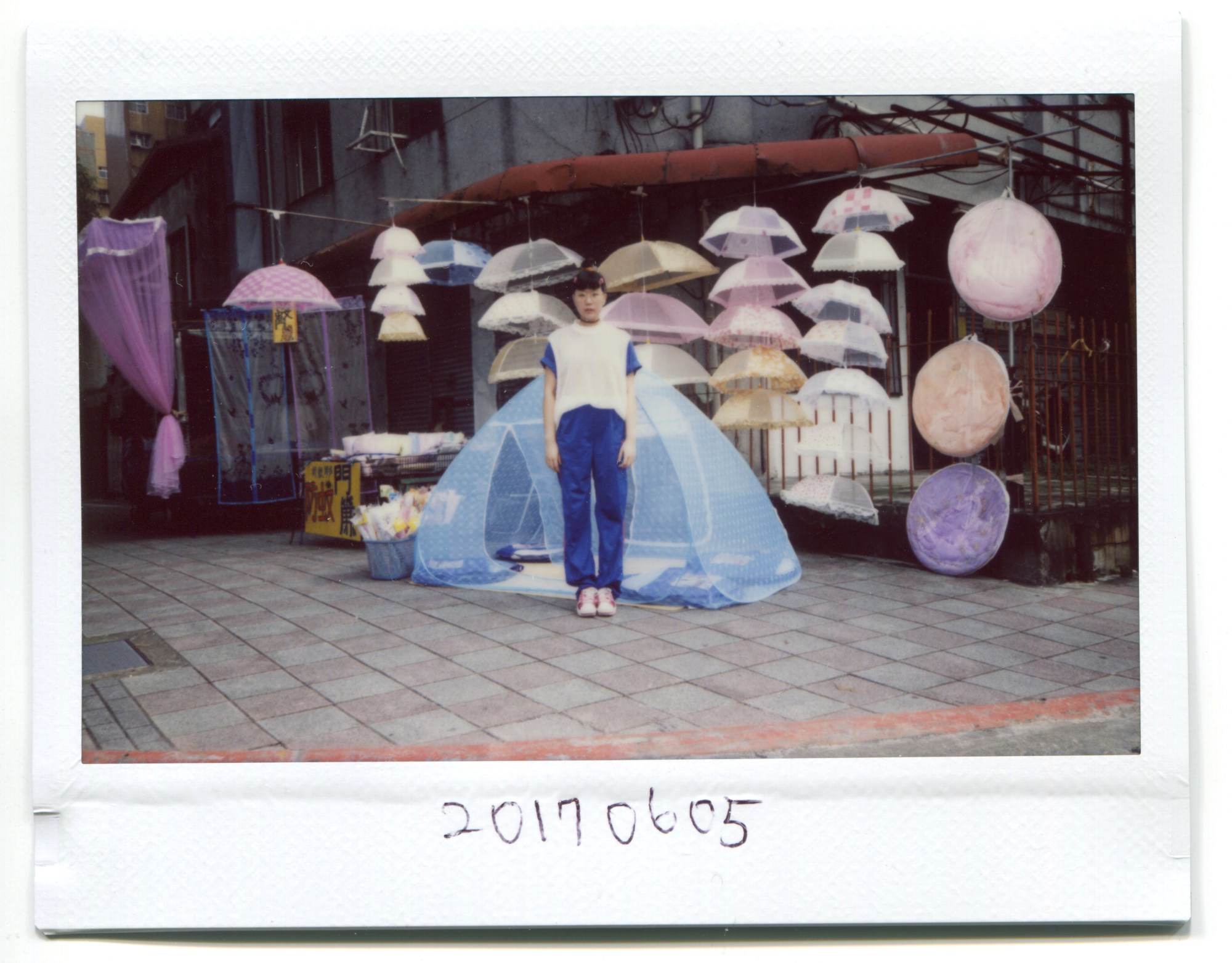

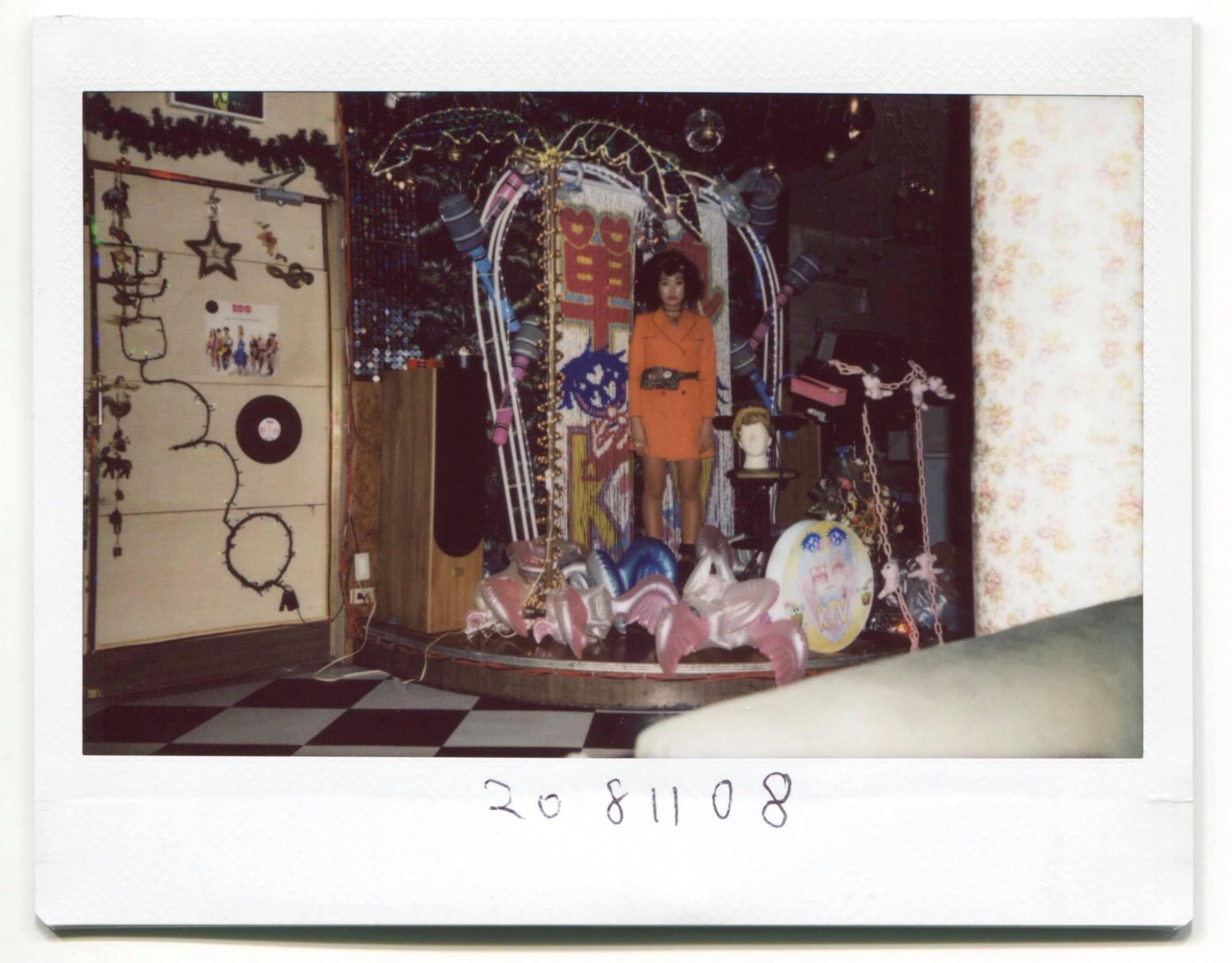

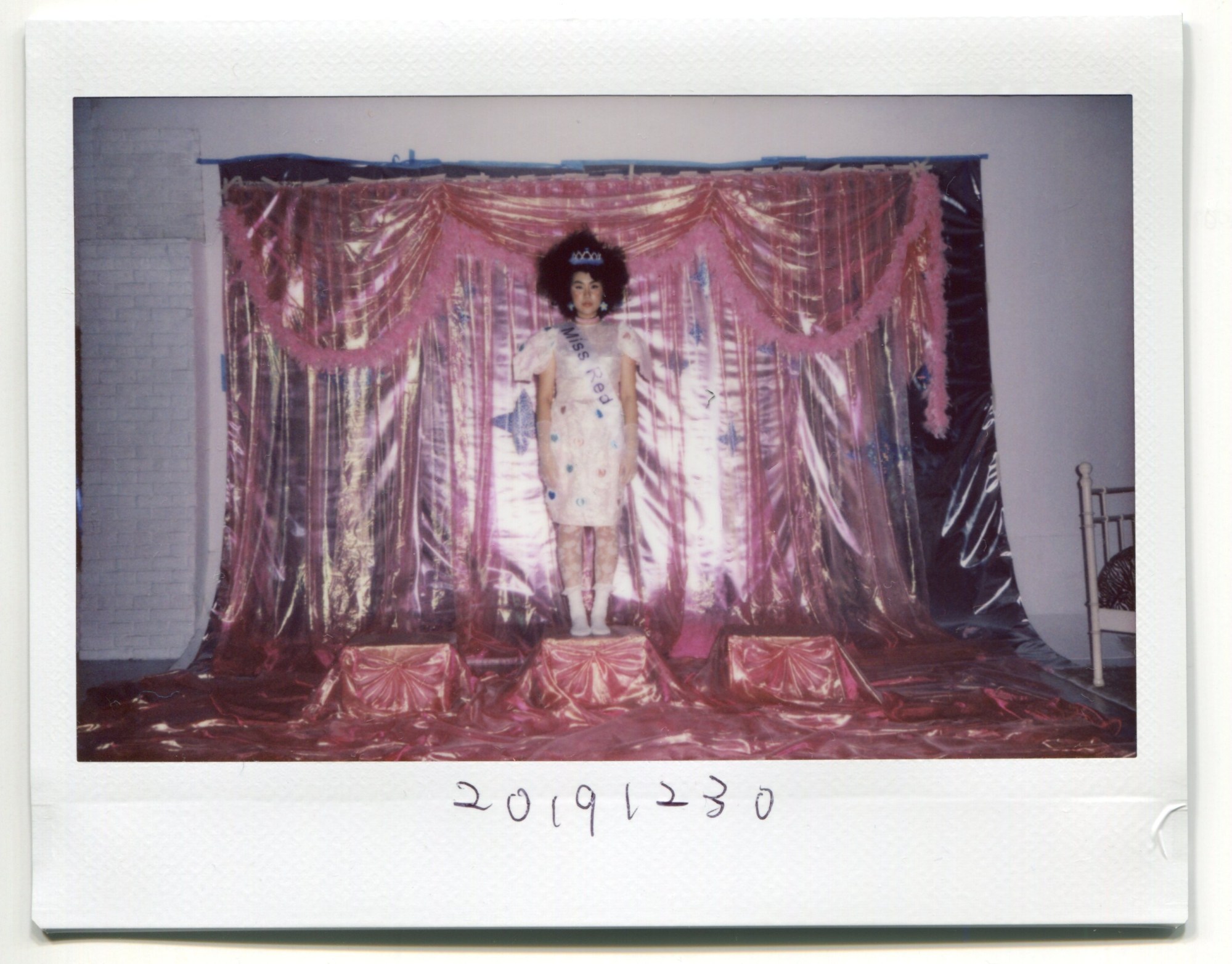

But equally important to Pin is colour. She’s drawn to Mika Ninagawa’s oversaturated photographs of flowers, goldfish and landscapes. “I love everything that is really eye-catching,” Pin says. “You can tell by looking at my work and outfits. I love a scene with a lot of information.” From overstuffed rooms painted pink and packed with cuddly toys, flags and giant plastic ice-creams, to a flamboyant set designed to look like a beauty pageant for Taiwanese model Kiwi Lee Han’s cosmetic commercial, her polaroids are filled with unconventional colours and curios.

With a day job at vintage shop called Flower Whispering, Pin always matches her locations to her clothes, inspired by early 00s fashion, as well as the costumes in the manga books she devours. “Nowadays we live in the era of information exploration — different clothing styles have become more accessible to young people,” she says. “[But] some young people treat culture instantly, blindly following trends without knowing what they want.” Recently, Pin has become fascinated with astrology, reading her daily horoscope and picking her outfits according to her daily colour.

The artist finds endless joy in the fantastical street scenes in Taiwan, where colourful advertising boards and written slogans, temple gods, mosquito net vendors and clothing lines, serve as the cinematic backdrop to her portraits. “Taiwan is a country full of cultural diversity,” she says. “It has been colonized by a lot of other countries,” including the Dutch and Spanish in the 17th century, followed by the Chinese in the Qing Dynasty and Japanese forces in the 1900s before their defeat in World War II. “Walking on the street you can see a conflict of cultural buildings, messy but somehow reasonable.”

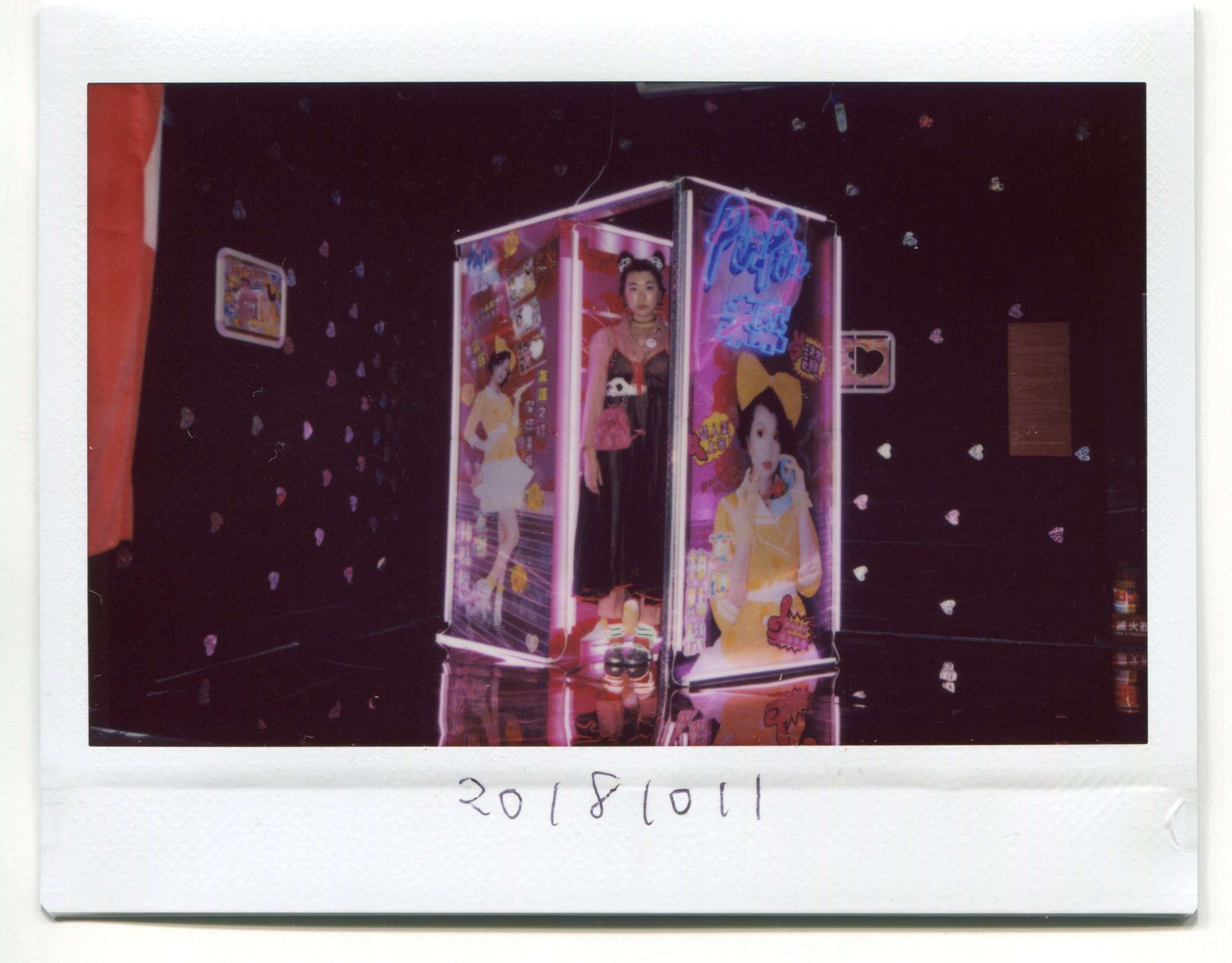

The 31-year-old artist incorporates her installation work into the polaroids too, such as one titled “Single KTV,” in which she set up a karaoke booth in a shopping mall and invited strangers to join or watch her sing a love song. “I have only had one boyfriend in my life,” Pin says. “After we broke up I’ve been single for over 10 years. In Taiwan people really like to sing karaoke. When I go out with my friends I sing some love songs for fun… But after I sang the love song, my friend looked at me in pity, like he was so sad for me because I don’t have a boyfriend.” The portrait “Single KTV,” and Pin’s body of work as a whole, intends to challenge society’s view that single people are lonely and depressed, and counter the pressures placed on women to find a partner.

Pin’s images are decorative, kitsch and playful, but at their core is the sense that life itself is fleeting and should be embraced. The photographs are a collection of memories — some bold and political, others unexceptional and mundane: from graduation, dinners and festivals to long walks. All of them imbued with nostalgia and magic. “Polaroids fade over time. My proof in documenting the world before the end will fade as well,” Pin says. “But the idea of images disappearing is very suitable for the end of the world.”