These days, how many photographers set out to a remote area, learn the local language, stay for a couple of years, and produce a body of work that ends up in some of the biggest museums around the world? The answer is, of course, not many. Immersing oneself in a community, and really becoming ‘at one’ with it has always been something generally more reserved for anthropologists than your average photographer. Such dedication outside of this academic practise is rare. Dutch photographer Bertien van Manen (1942), however, has employed this tactic throughout her career.

Some of the incredible results are now on show as part of a vast retrospective at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum of Modern Art. Initially starting out as a fashion photographer in the 1970s, she decided to change course after seeing Robert Frank’s photobook The Americans (1958), a personal and poetic masterpiece that offered a glimpse into both the high and low strata of American society. The book inspired her to concentrate on her own projects, taking a more spontaneous, unforced approach than she had before.

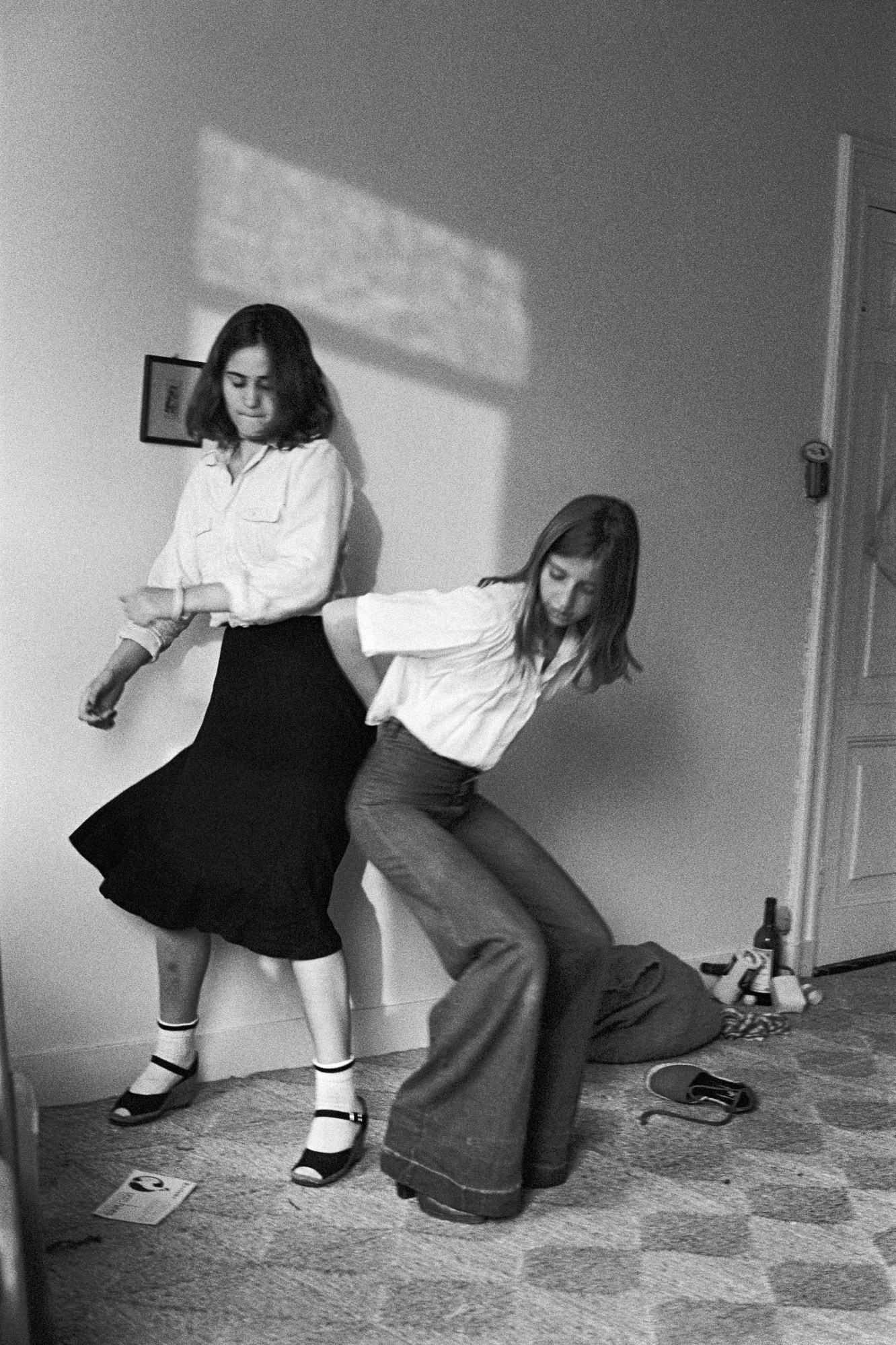

Much like her hero, Bertien’s initial work was defined by documentary photo reportage, shot in straightforward black-and-white which, up until the 1980s, was an important and popular genre. Since then, however, her work has gradually evolved into a poetic form of colour photography that reveals enduring, personal relationships with her subjects. Take her seminal series A hundred summers, a hundred winters as an example; it covers her travels through the former Soviet Union, and first appeared in book form in 1994. Now, it’s almost impossible to get your hands on.

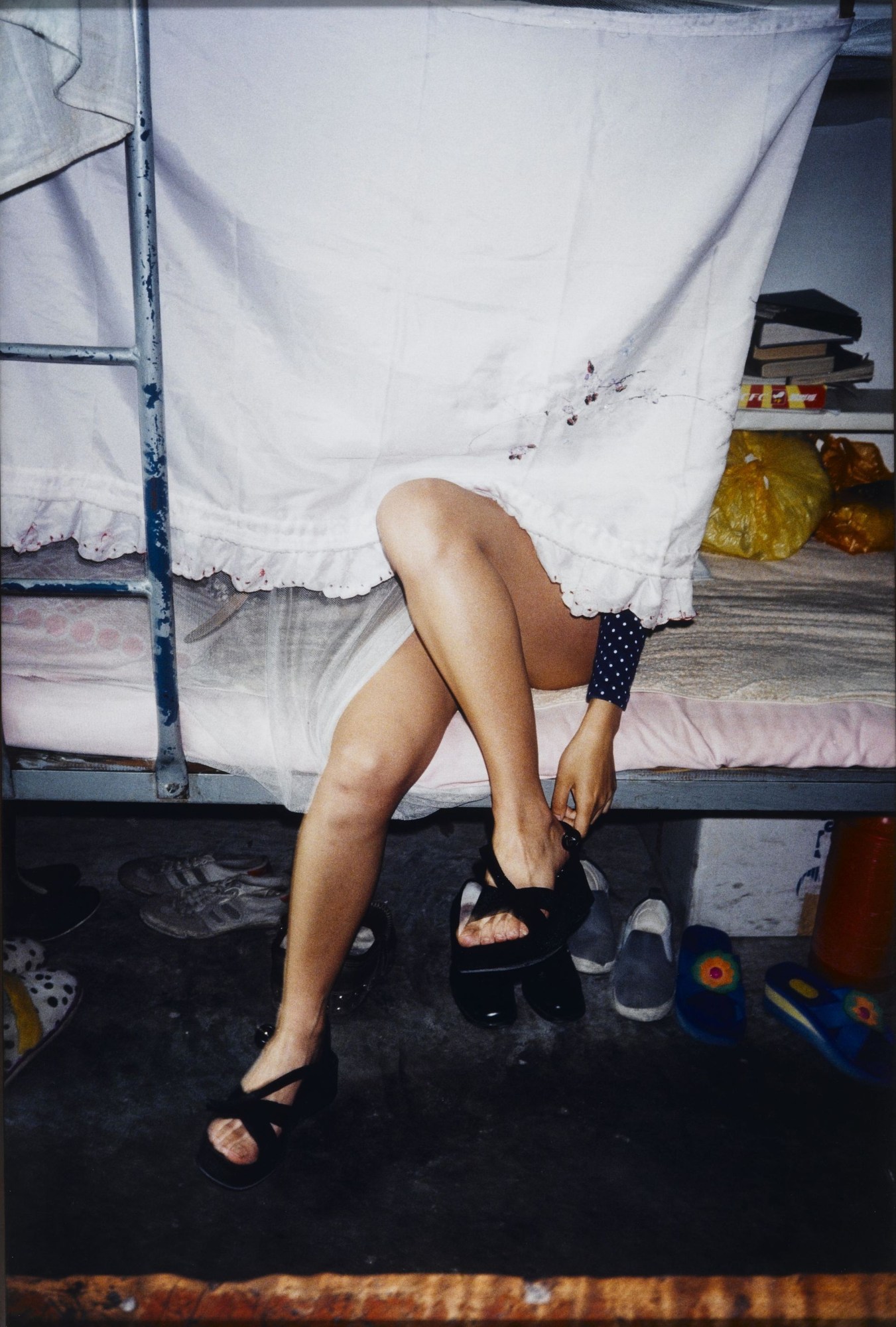

Bertien, who had studied Russian at university, travelled to the Soviet Union following its economic and political collapse in the early 90s — not to report on any particular historical events or people, but rather to provide an account from life within. For a couple of consecutive years, she went into the poverty-stricken underbelly of Russian society, staying in the homes of families, capturing her hosts and travel companions, who often became her friends. That sense of intimacy is palpable throughout the series. Shot on a simple, small handheld camera she was able to get incredibly close to her subjects. We see a young couple cuddling in bed; a girl posing proudly in her finest gown in front of a relative’s portrait; a young and elder woman taking a bath, young men running around in their army gear. Rather than succumbing to the desire to romanticise and fetishise poverty — a tendency often seen in photographers capturing remote communities — Bertien’s photography is earnest and optimistic.

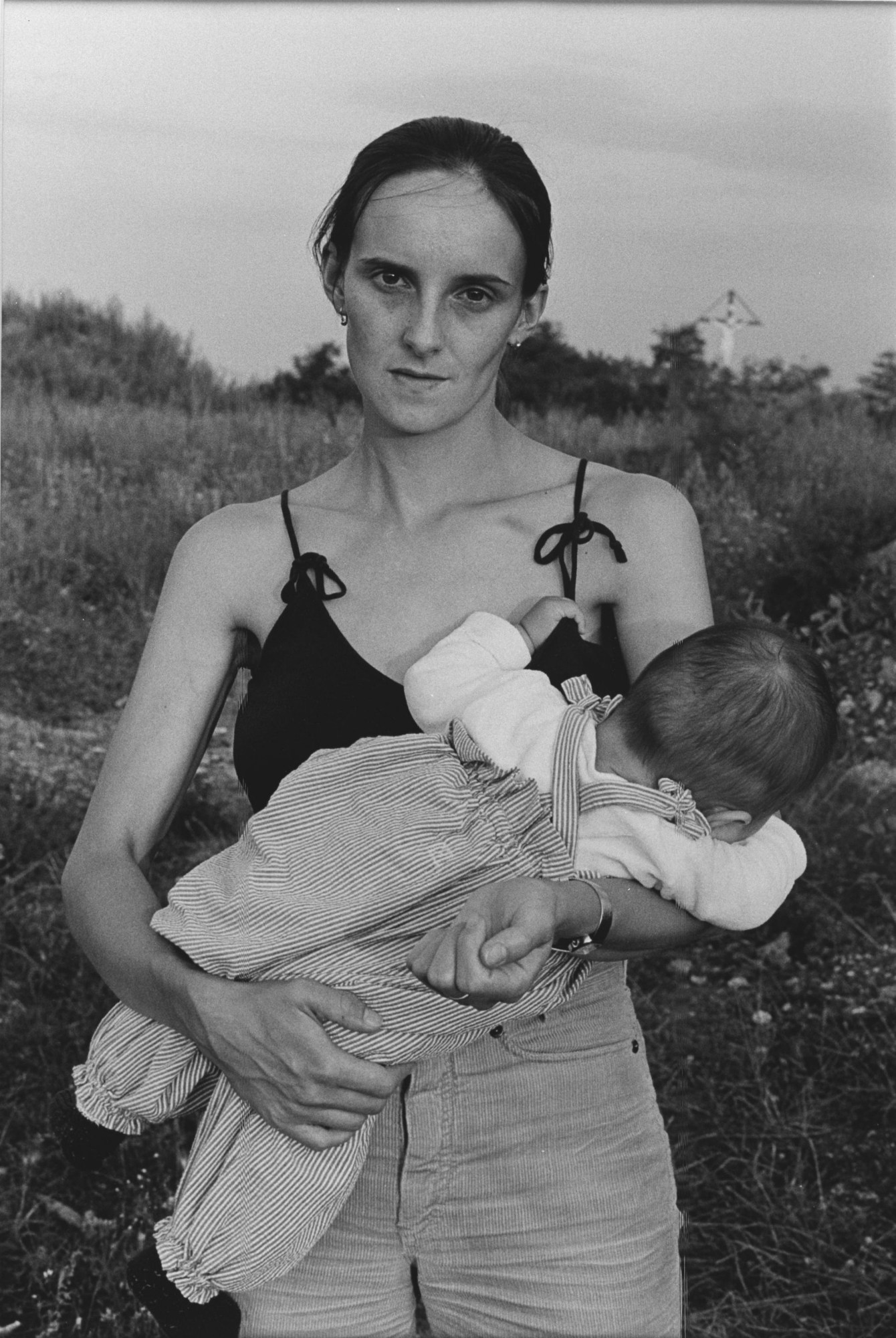

Another seminal work is the series she shot during her time in the Appalachians, a mountainous region of the United States that, in addition to its beautiful unspoiled nature, is also known for its abject poverty. There, Bertien became acquainted with Mavis and her husband Junior, who worked in the mines. They lived in a trailer on a hill overlooking Cumberland, Kentucky. Bertien stayed with them and listened to their stories. She published the confronting and intimate photographs she took of the couple and others in the 2014 book Moonshine. Other works on display at the Stedelijk Museum of Modern Art include her 1970s series on everyday life in Budapest under the yoke of communism, a black-and-white series on female migrant workers and nuns in the 1980s, her series on young Chinese people coping with changes in society in the 1990s and the sensitive landscape photos she took after losing her husband in 2010.

Bertien, who was incredibly flattered to have been approached, insisted on combining each of her series with the work of another photographer she herself admired. These turned out to be fourteen in total, including established photographers such as Nan Goldin, whose works offer an intimate and heartfelt ode to her flamboyant friend Cookie Mueller, Rineke Dijkstra‘s famed Beach Portraits, Martin McGagh’s series about boys on the brink of manhood set against the backdrop of Irish suburbia — just to name but a few.

Their works, which are beautiful in their own right, provide an interesting balance to Bertien Van Manen’s work, giving her pictures a broader context, emphasis, contrast or counterbalance. And while we appreciate Bertien’s modesty, the photographer has no reason to feel too humbled: her vast body of work has finally landed itself a spot which it deserves.

‘Beyond the Image: Bertien van Manen & Friends’ is on show from now till the 4th of October at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Visit here for more information.

Bertien van Manen, Novokuznetsk, Siberia, 1991, from the series: A Hundred Summers, A Hundred Winters, chromogenic colour print, Collection Nederlands Fotomuseum Rotterdam and Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.