Joel Meyerowitz: From rising stars to industry heavyweights, i-D meets the photographers offering unique perspectives on the world around them.

It’s estimated that in 2018, over one trillion photos were taken. Of these, 100 million were uploaded to Instagram every day, accruing around 4.2 billion likes between them. In 1962, when a then-24-year-old Joel Meyerowitz quit his job on a whim and began photographing the streets of New York, a camera may have been an affordable and accessible item, but the medium wasn’t largely understood — barely considered an artform, much less a language that helps us understand the world around us.

“I borrowed this camera, I bought two rolls of colour film and I went out onto the street… but I didn’t know what the fuck to do,” Joel says in a thick Bronx accent over FaceTime. Warm, engaged, he seems incredibly enthusiastic to discuss the work he made 60 years ago, answering each question first with a thoughtful pause. “I didn’t really know how to work the camera, I just had to figure it out, so I walked around and thought, what do I want to photograph?”

He quickly found what he was looking for. Placing his lens towards the street Joel found lightness, darkness, tragedy, humour, joy — fleeting moments of absurdity amongst trudging normality. He saw life in all its mundanity and all its brilliance, and with his contemporaries of this era, changed the way we visually communicate. In 2019, his work belongs to a canon of American photography that has conveyed the historic truth of the street.

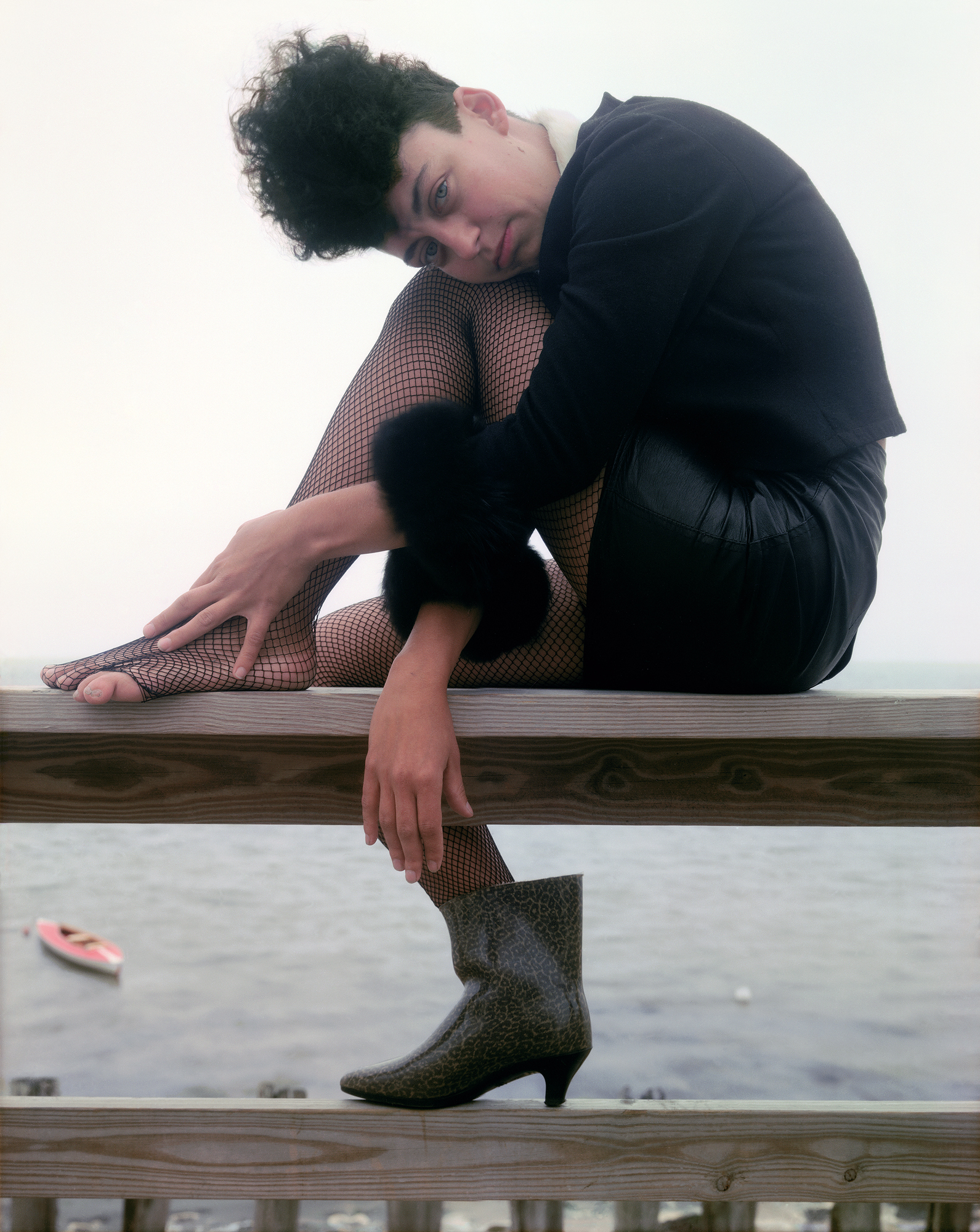

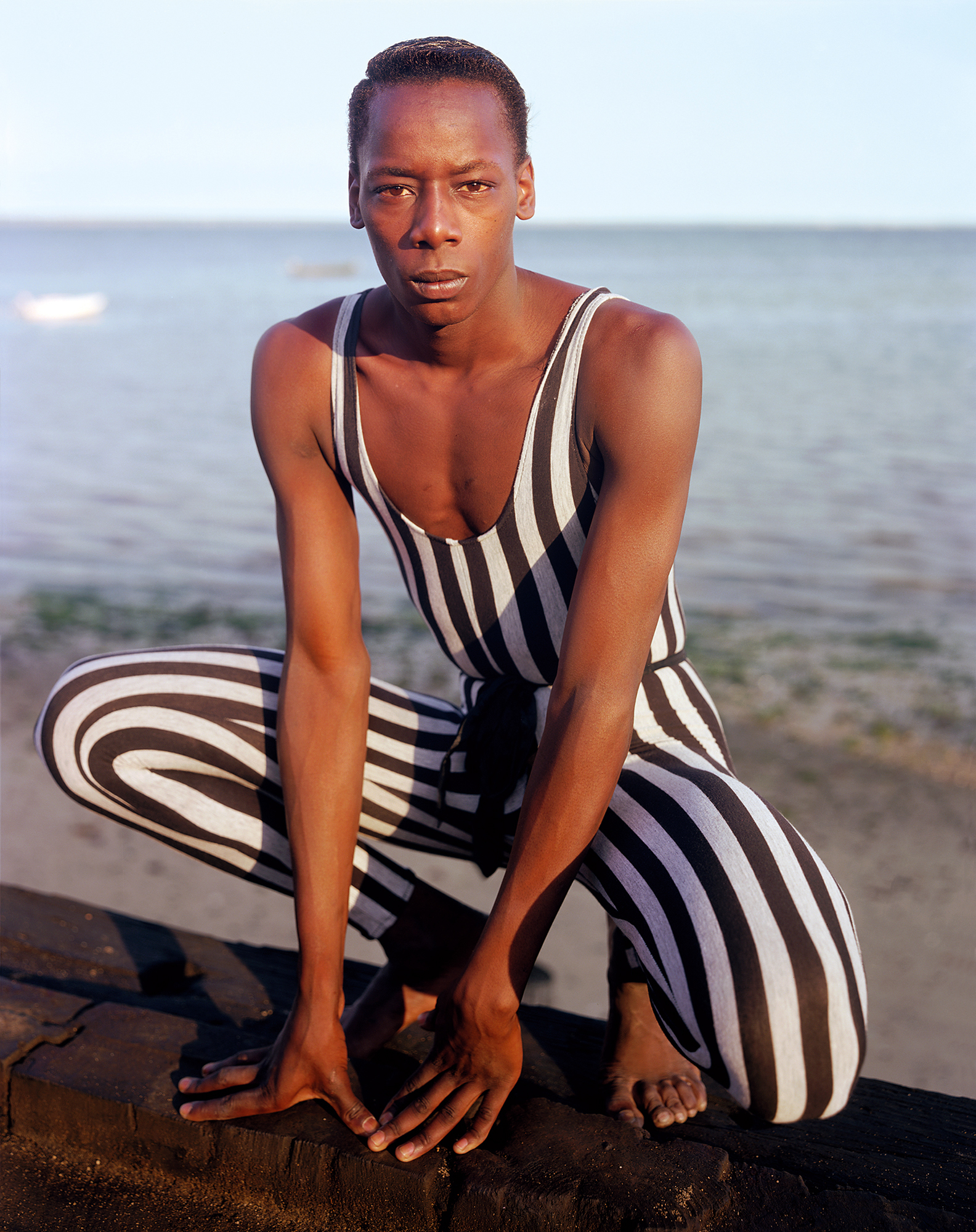

Joel’s latest publication bears the hallmarks of his precise photographic style, but takes us away from the vignettes of life in the city he’s better known for, into Provincetown, a small community on a peninsula south of Boston, 300 miles away from his home in New York City. The town was a sanctuary of tolerance and peace for the queer community in the 70 and 80s, when the LGBTQ rights movement raged in parallel to the devastating fallout of the AIDS crisis. Joel arrived to capture its wide open landscapes but stayed to enjoy its liberal freedom and fertile creative scene. “Because it’s land’s end, people often go there to escape their lives in the city,” he says. “It’s always been a place of creative freedom… 19th century painters, early 20th century playwrights, poets and writers went there… contemporary painters went there.”

The resulting book, Provincetown, released next week, is full of quiet, tender and engaging portraiture. Sanguine expressions bathed in cerulean evening light; faces that tell a much bigger story than simply what’s captured within the frame. Loss, fear, escape, faith, optimism are all present. It’s a series of images that would’ve remained unseen, had an inquiry not been made into Joel’s personal archive to better understand style in the 70s. Just one of many collections Joel has yet to publish. Here, we discuss with Joel his expansive body of work, why he thinks photography can never be made the same way it once was, and Provincetown.

Tell me about the first time you truly discovered the power of photography. Do you remember the first time it had a profound impact on you?

I actually do. It’s how I began. I was an art director for a small advertising agency in New York and I had done a little magazine and my boss hired the photographer Robert Frank to shoot it. I knew nothing about photography. I went to the location and he was a furry little quiet guy who paid me no attention whatsoever. I was watching him work, because I had never seen a photographer work like that before, and it was so magical. Every time the camera clicked, the action seemed to be at a peak moment. I couldn’t believe he was getting these moments of beauty. When I left and walked out onto the street, the world overwhelmed me. Everything I saw seemed to have importance.

When I got back my boss said, “How was the shoot?” and I said it was great… I’m quitting on Friday. He said, “Oh no was it a disaster?” and I said it was the most amazing thing I ever saw, the world is full of amazing photographs and I want to go out and take them. He said, “You have a camera?” and I said no, and he said “You shmuck! How are you going to make photographs without a camera. Here, borrow mine!” and he reached into his desk draw and he gave me his camera. On Friday, after the pictures came back, and I had designed the booklet, I left the job and I have never been back since.

What were those early pictures you made like?

They’re quite innocent. On the very first day I made a roll of pictures and I took them into the lab. The next day I went to the lab to pick them up. I’m laying them out on the lightbox and there was another guy in there, with a beard and long hair, looking at his pictures on the lightbox. So you know, he looks at my pictures and I look at his, and we begin to talk about photographs. That was Tony Ray Jones. We started shooting together, as a way of learning how to be on the street. We were able to look at the pictures together, projected on a screen at night in my apartment, so that we could learn how to talk about pictures. Tony left New York after his visa ran out and came back to England and became a mentor to Martin Parr.

In these early years, when it was beginning to be be understood what that art form was, did you feel like you were a part of a vanguard of artists creating something new, or was it less tangible what was happening in the moment?

It took a little while for us to see it. Individually and together. Because I was a painter beforehand, and I was in graduate school for Art History. So I understood painting, abstract expressionism, but you know, me and Tony, and Tod Papageorge, and Ralph Gibson, Garry Winogrand, these are all people who were turning to photography who might’ve been artists, I had to give up being a painter to be a photographer, because there was something about it that was a stimulating call-to-action. It felt like it was the right tool for the way urban life felt, at that time in the 60s. I saw that more and more young people, your age and my age then, were turning to photography because it was a sort of poetic art-form.

In a way, I was in that moment, and my connection with Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Tony, Garry… there were quite a big range of photographers out there who made their livings in the magazine, but who thought of themselves as serious artists. But that made it exciting.

Did you ever connect with Robert Frank later on?

Yes, I did. He always laughed at me because I would see him and say, ‘Hey Robert I’m Joel, remember…’ and he would say ‘Of course I remember you…’ Over the years I became friendly with him.

Thinking about the story of Vivian Maier, and how she was able to create such interesting work in total anonymity, what resonance did that have with you as a street photographer of the same era?

You know, in the early 60s, there was only one gallery in New York, so photography wasn’t seen very much. You could go to MoMA to see a show, or maybe this one gallery called The Underground Gallery. The collective were a small group of people who knew each other. But we did have John at the Museum of Modern Art and I could go and bring my work to him. Vivian didn’t have that, she was living in Chicago, and she was working as a nanny, so when she took the kids to school, between picking them up and leaving them off she had a few hours in the day to make her photographs. So in a way she stayed invisible, she didn’t mix with other photographers, she didn’t engage…

I have to say I am part of her discovery, I don’t know if you know that… About eight years ago, John Maloof, who was about your age, bought the stuff from the storage place and when he discovered he had all these pictures in there he contacted me and said “I’ve found this case of pictures and I think they’re really interesting, can I send you some and you tell me what you think?” So I gave him my email and he sent them and I was just bowled over. I thought, she’s the real thing… although of a certain era and a certain point of view. But nonetheless her instincts, the way she worked with people, how she could be invisible and still be close, these were all characteristics of a good street photographer. So I called him, and said, you’ve really discovered something.

There’s always a canon in the history of anything. Music, photography, whatever. And then someone comes along and they have to sort of fit in. All of us who were there already have to move over one space. And you know, that’s incredible.

Can street photography be made in the same way now as it was back when you and Vivian and your contemporaries were discovering it?

Yes and no. Sure, if you have 35mm and you want to go out and disappear in the crowd and make pictures of what you see, absolutely. Is the street as innocent as it once was? No. Most people didn’t want to spend money on a camera, on the film, and carry it around with them. So people didn’t take pictures on the street. So therefore there was a kind of innocence. When I would make pictures on the street, or Garry, or anybody, people didn’t look at us if we were doing something that was going to appear somewhere… I think today’s shooting on the street has a very different feeling. There is no street that you can stand on where there isn’t somebody doing [gestures staring at a phone] you see a hundred people in the course of a block with a phone. There’s a kind of posing and consciousness, that human activity looks like on the street, that I think undermines the best qualities of street photography.

What do you think about the fact it enables people to be so much more engaged with photography and access so much of it, could that ever be an inherently negative thing? iPhone photography has allowed the medium to flourish and become this thing that can often bring people together, at the cost of being able to create imagery that stands out as easily. On this, do you think it has advanced or devalued the craft?

That’s a good, rich question. Thank you. I think it’s a double-edged issue. On the one hand, I celebrate the billion people who are now making photographs. They’re going to add to the history of photography. At the same time, it’s made it so generic, everybody does it… there’s a sameness to a lot of photography that is boring. You must see a million boring pictures when you look at your Instagram feed, or when you use Facebook, who cares? But you also sometimes see really interesting, sometimes quirky, thrilling moments of human behaviour.

I do see a lot of engaging work online. I meet somebody, we talk photography for a few minutes, I go and I look at her website and I think… holy shit, this is a poet. I had a feeling she was interesting. Or I look at somebody else and I think… more pussycats. It’s a gamble.

What first drew you to Provincetown as an area and why was it such fertile ground for shooting beautiful portraiture?

I was at a point in my life where I needed to change something. I realised I had to use a bigger camera, other than a 35mm. My best friend who was a painter said, you oughta go to Provincetown. He said it has a main street that has action like Greenwich Village. He said it has street life and nature, that way you’ll be able to work any way you want. I found a house to rent and I started making pictures. My pictures were mostly of landscape. But somewhere in that first year I made a few portraits and those portraits really did something to me. So each summer, over the next few years, I made portraits there.

When you talk about the area as something of a sanctuary, where marginalised groups could find shelter and community, was that something you were particularly interested in documenting or does that merely play in the background of your photography?

The latter is closer to the truth. We all knew the AIDS crisis was happening. It affected all of us… but I wasn’t documenting it. I was photographing the life of the town that I spent my summers in. And the town was everything. It was part of the overall worldview, which I had, which embraced everybody. I didn’t have to be one thing or the other.

How was the collection curated? Because looking at it, the first thing that’s quite interesting is that it’s female-heavy, and photography ostensibly tied to the LGBTQ communities in and around New York in this era are often very male-centric.

You’re right there are more women in there than men. I wasn’t making a polemic or a political statement about the AIDS crisis, but I was showing gay couples. There were a lot of pictures of people making love, that I photographed. Women making love, that they didn’t put in the book. I have a whole body of work that I did because my next-door neighbour was a gay woman who ran a gay hotel and I was invited into that hotel as the sort of resident photographer.

It’s funny, I think nowadays people are more focused on going and documenting something because things are more polarised, or divided, or compartmentalised. At that point it had a different kind of flow. In those days there were people who were still coming out, they were in the regular community, and then they moved to become part of a freedom, in a way. It’s hard to define, I just saw it as ordinary life.

The idea that you could be invited into someone’s bedroom to document them having sex strikes me as something that also couldn’t be considered as “innocent” nowadays as it was then. People must have seen you, the photographer, as something completely different to what a photographer would be considered now.

Yeah, and it happened so naturally. Gabriel — she’s in the book — was my next-door neighbour, we had dinner together, we partied together, we swam together. At one point she asked me if I would photograph her and her lover in bed. We were all naked all the time swimming. Because in Provincetown, if you live on the water, you just walk out your door naked and go in the water. That’s just how it is. So there wasn’t any sense of shyness. We did it in such an innocent way, it didn’t seem like I was making a heterosexual picture of gay women. It was just a picture. At one point she said, “You know, I betcha there’s some of the guests in the hotel who would love to have you take their picture.” It wasn’t like, I gotta do this. I gotta go to the brothel.

Joel Meyerowitz: Provincetown is available to pre-order here.