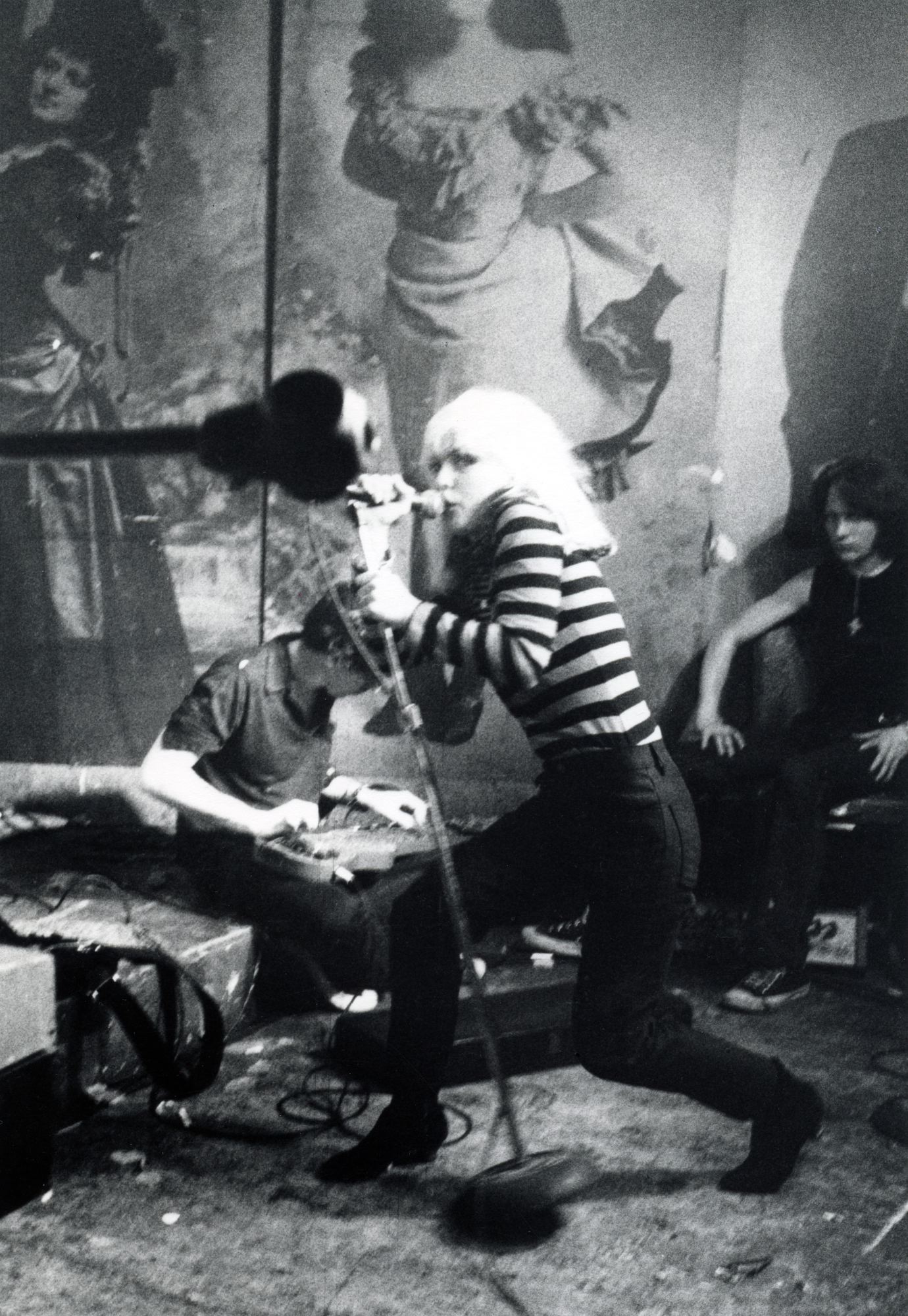

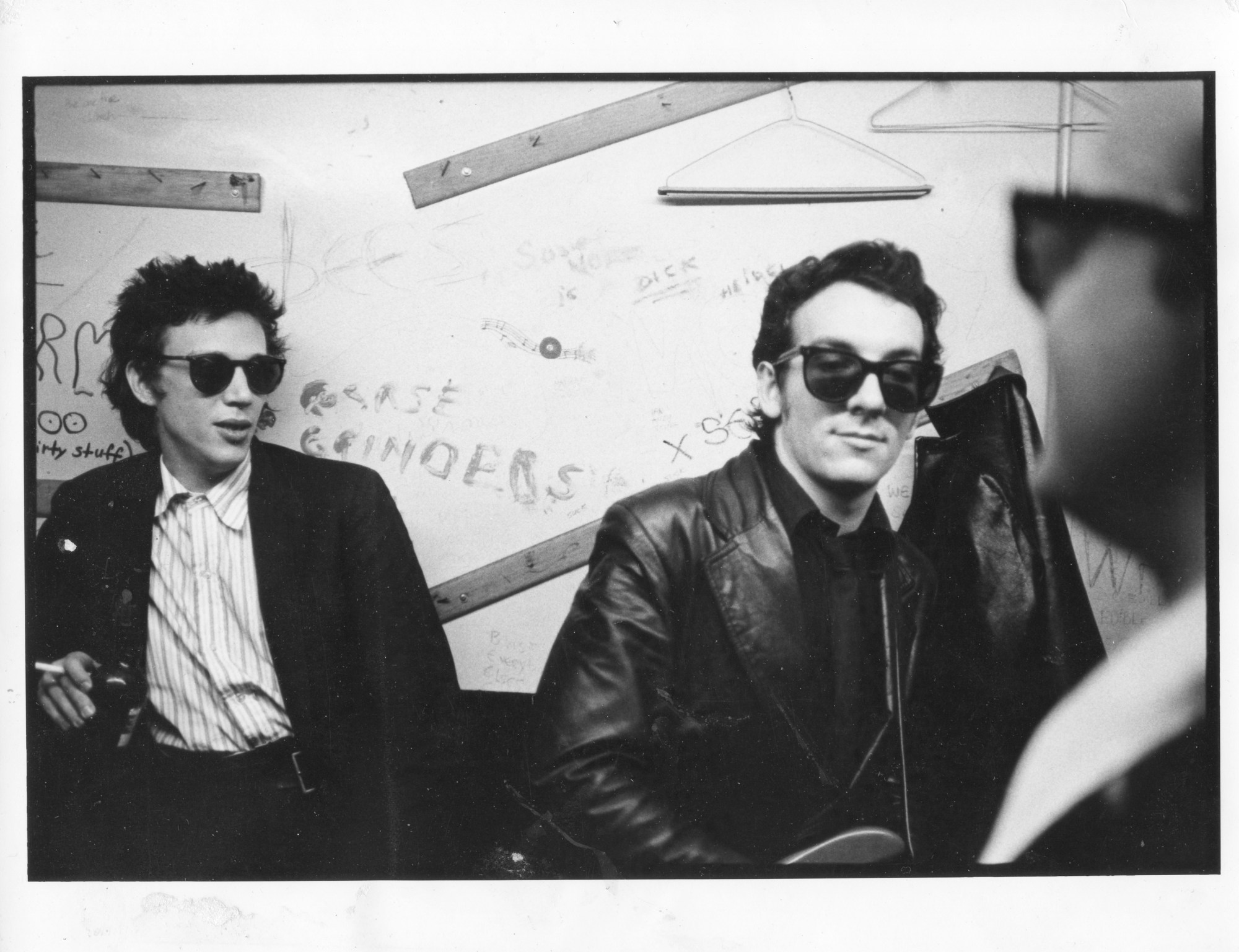

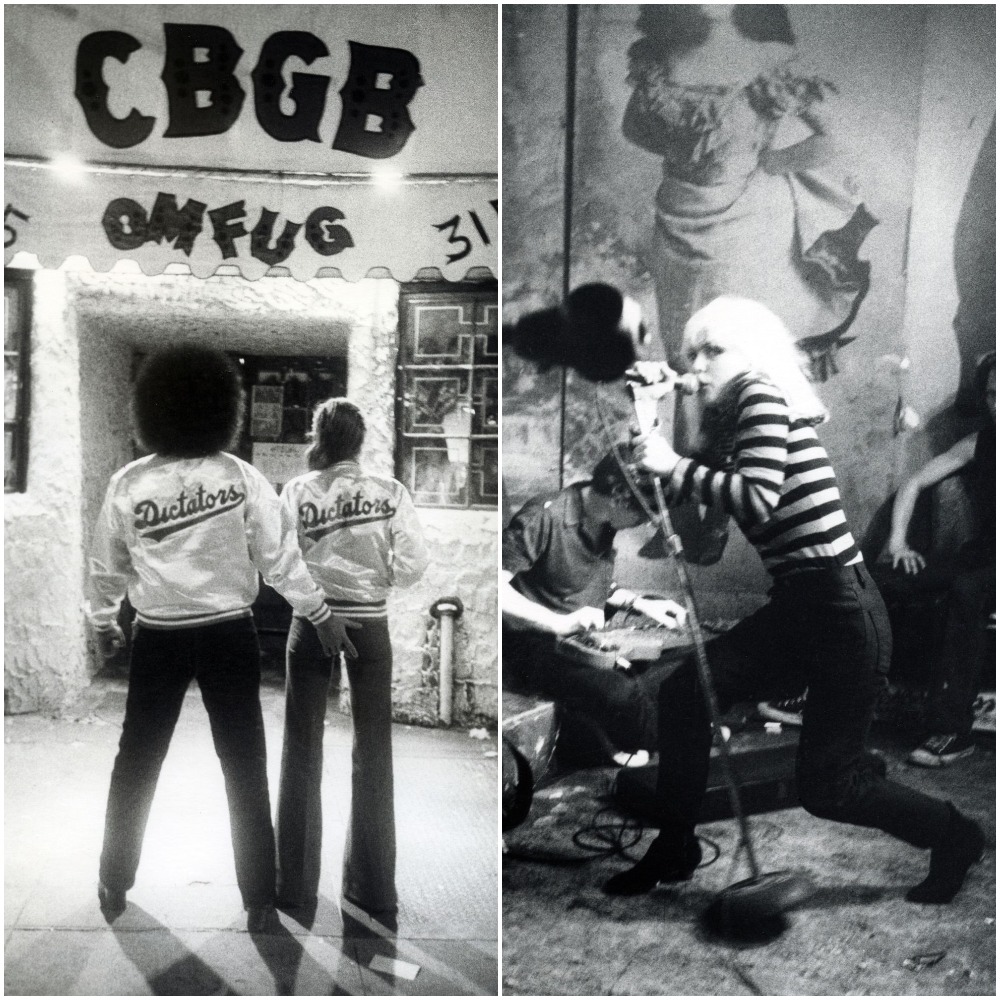

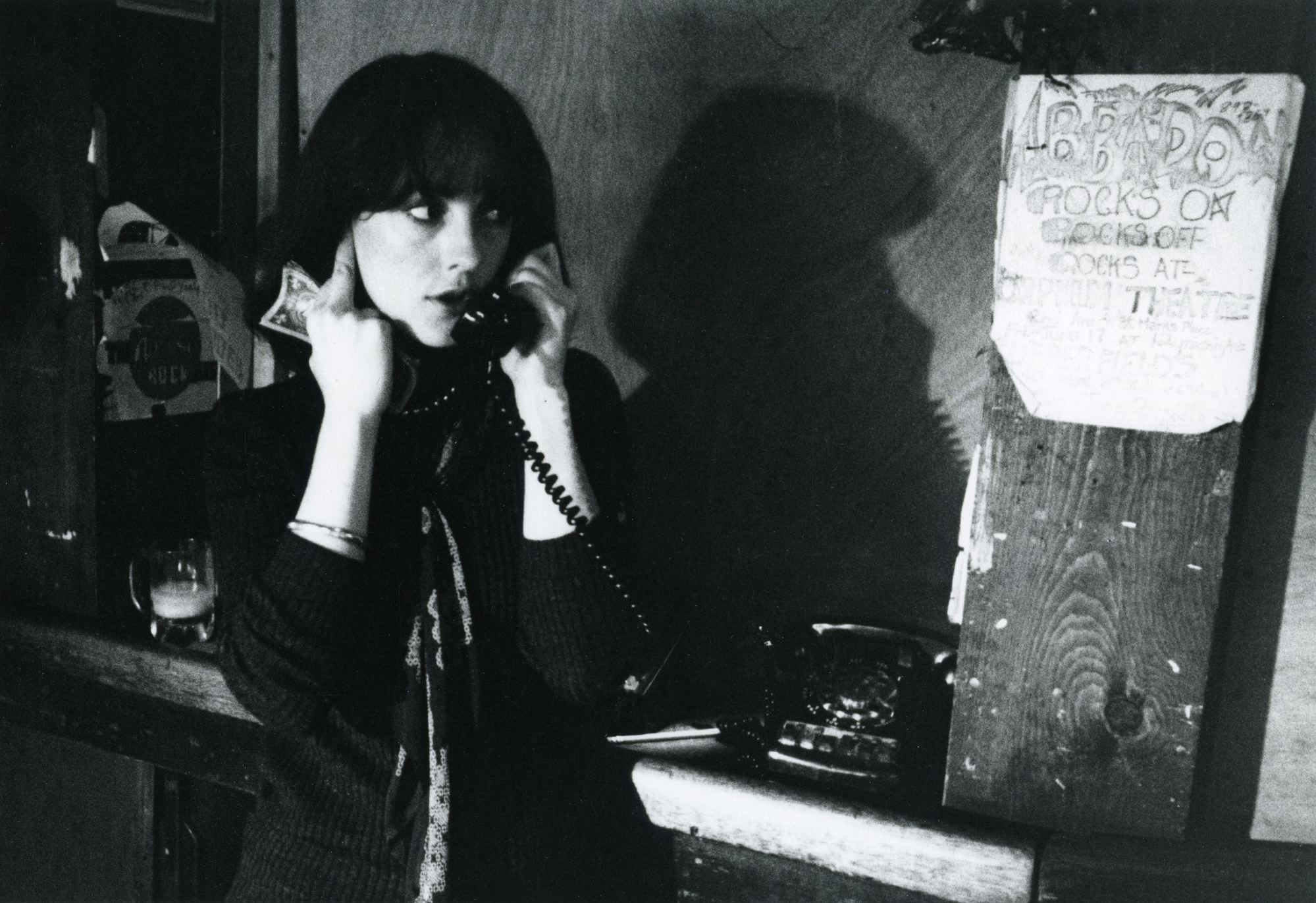

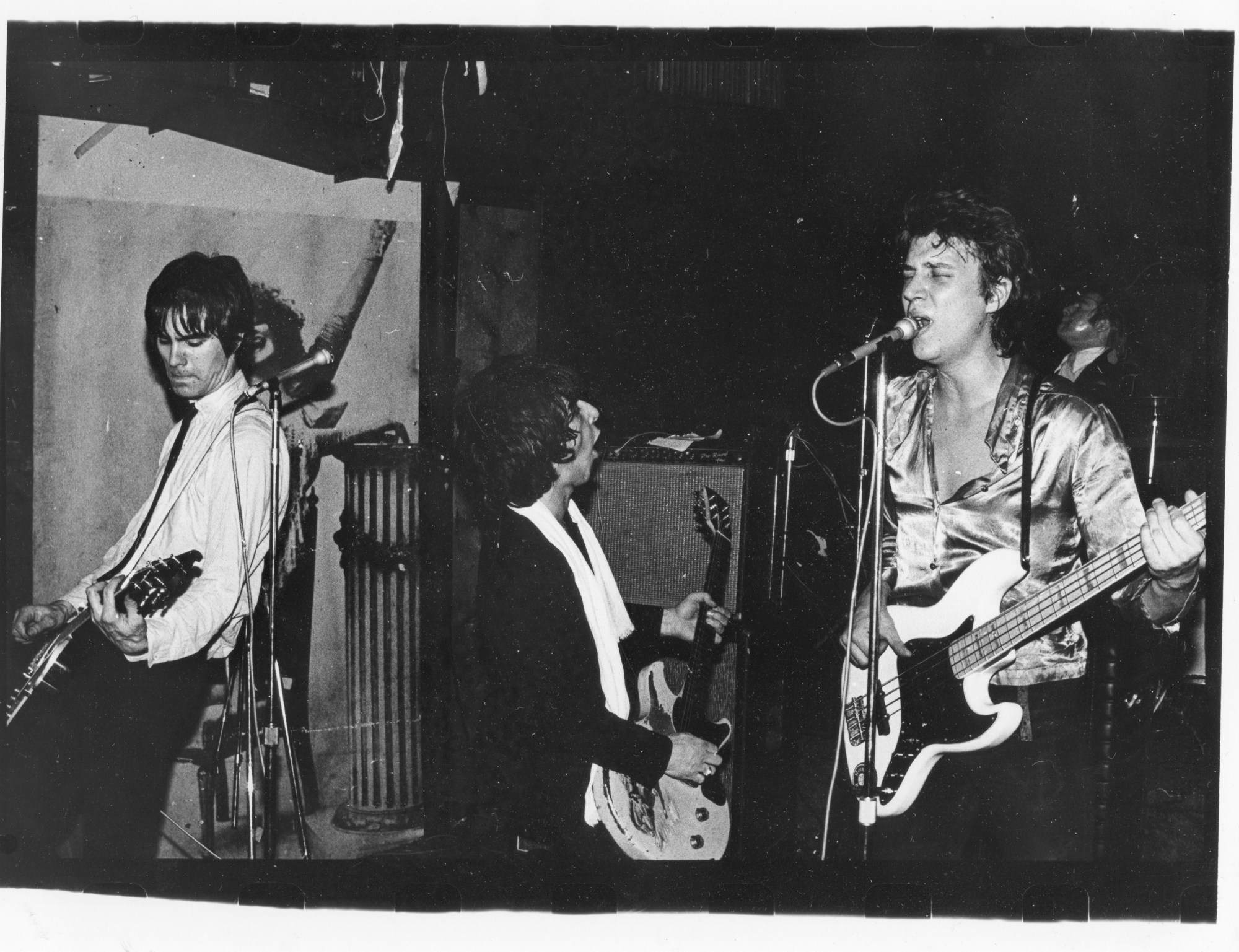

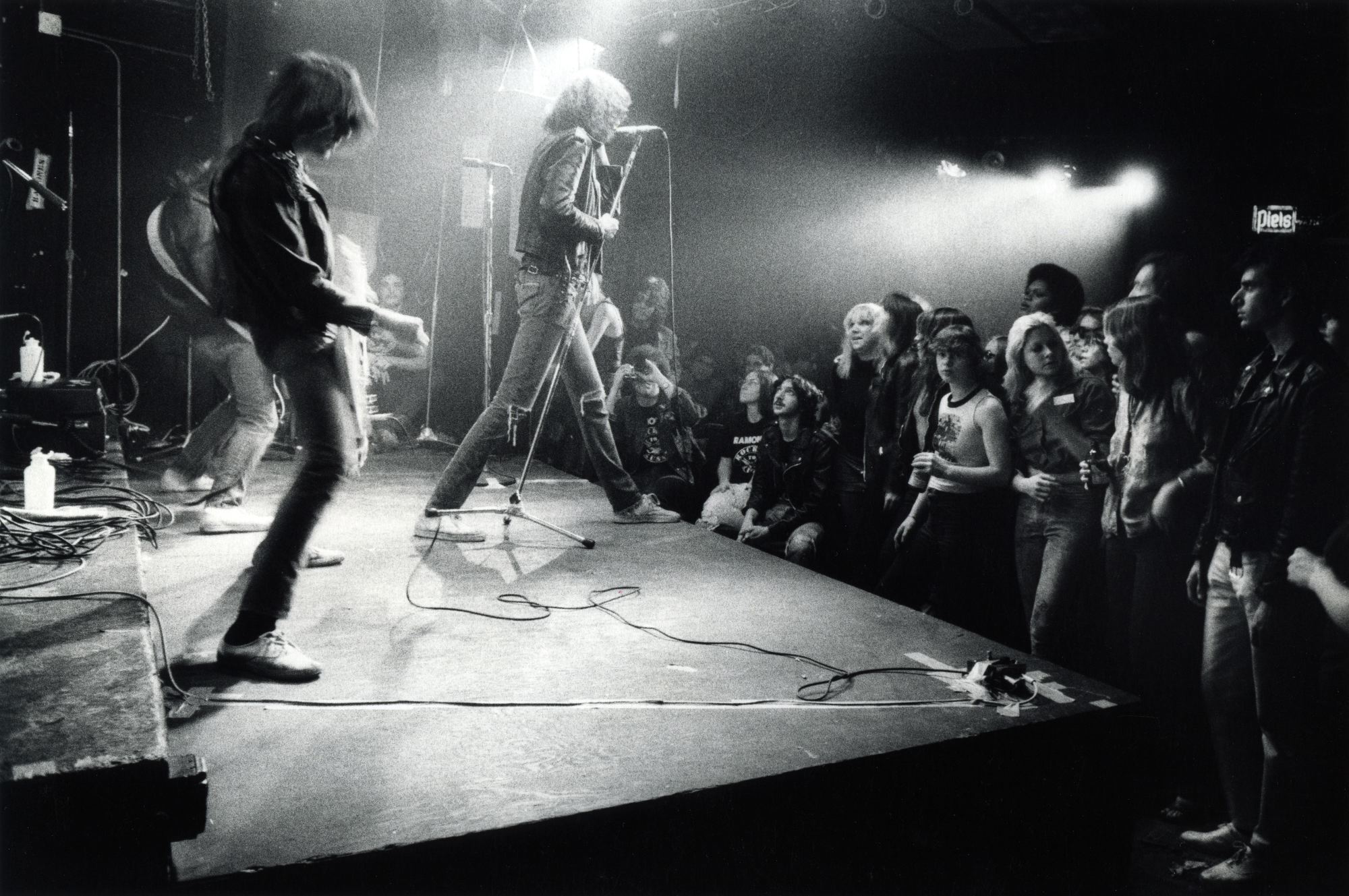

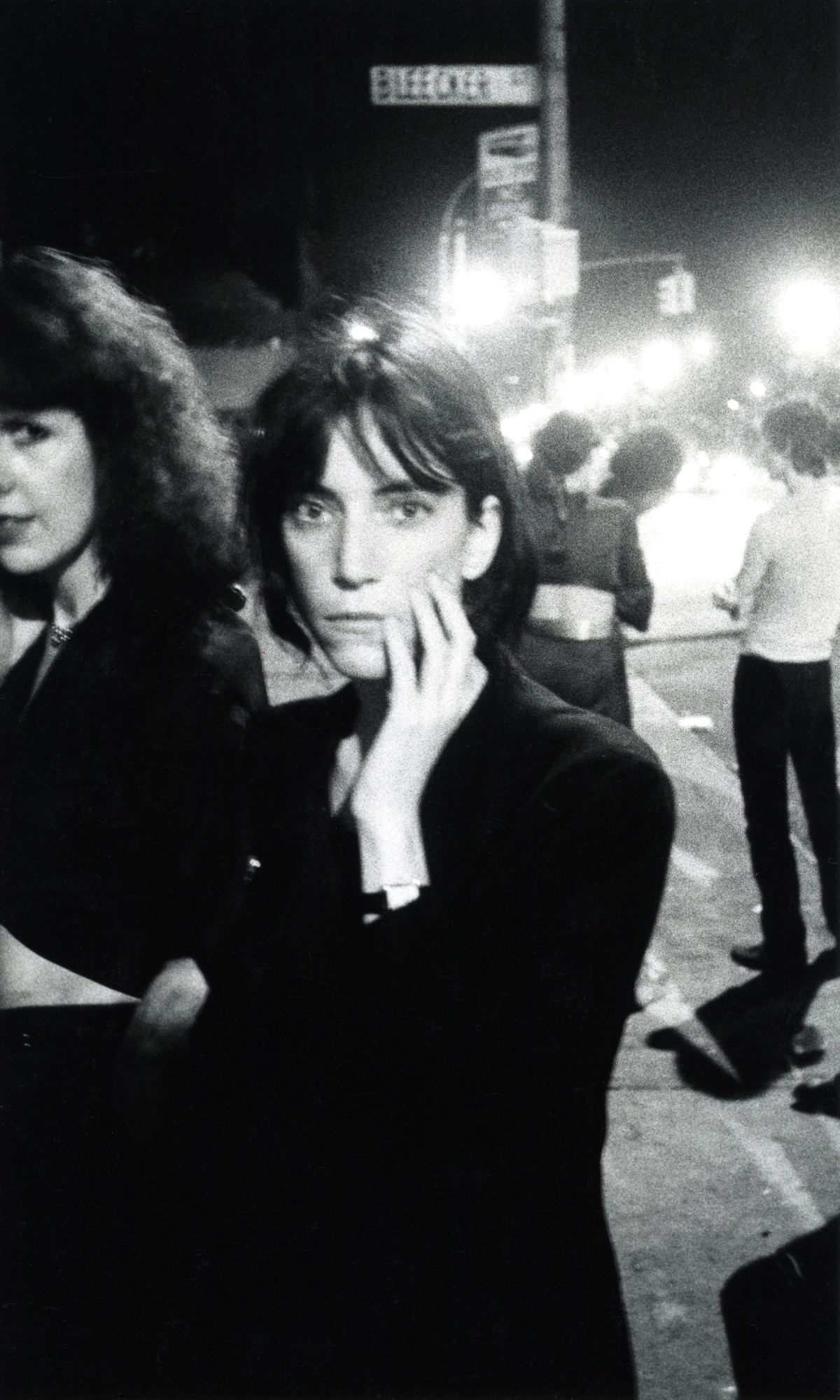

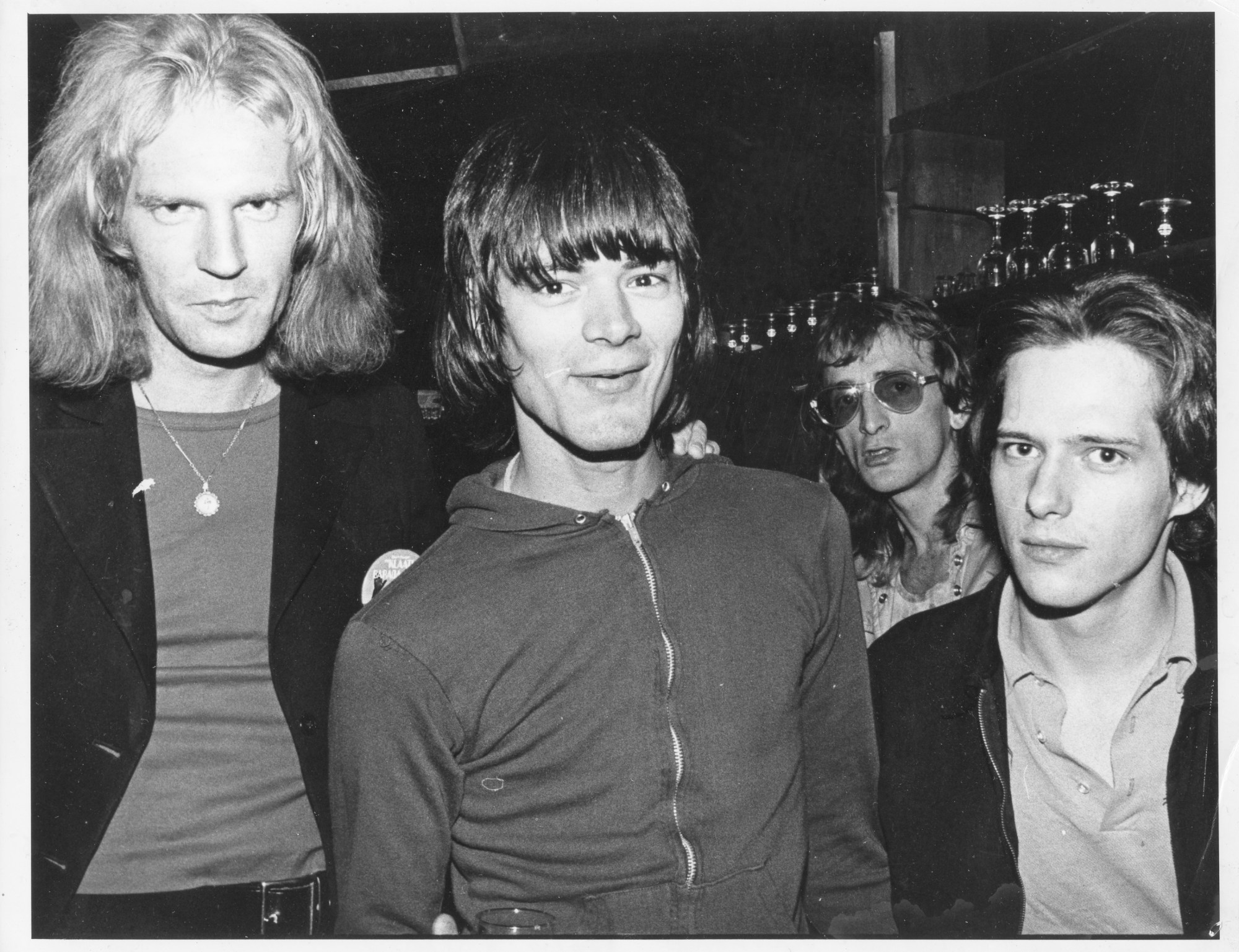

In the 45 years since CBGB‘s opened its doors on the Bowery, the club’s legend has hardly faded from memory. Perhaps this is thanks to the many iconic photographs, often taken by Roberta Bayley and David Godlis, that seem to suspend New York’s punk scene in time — like that of a young Patti Smith smoking a cigarette between sets or the Ramones crouched in an alley outside. Chances are if you walked into CBGB’s between 1975 and 1978, you’d be greeted by Roberta, seated at her post by the door where she’d collect the $3 admission. Occasionally, she’d pop back and take a few photos of her friends performing — like Richard Hell with his Heartbreakers, Talking Heads, or Blondie — often to print in Punk Magazine, where she was the chief photographer.

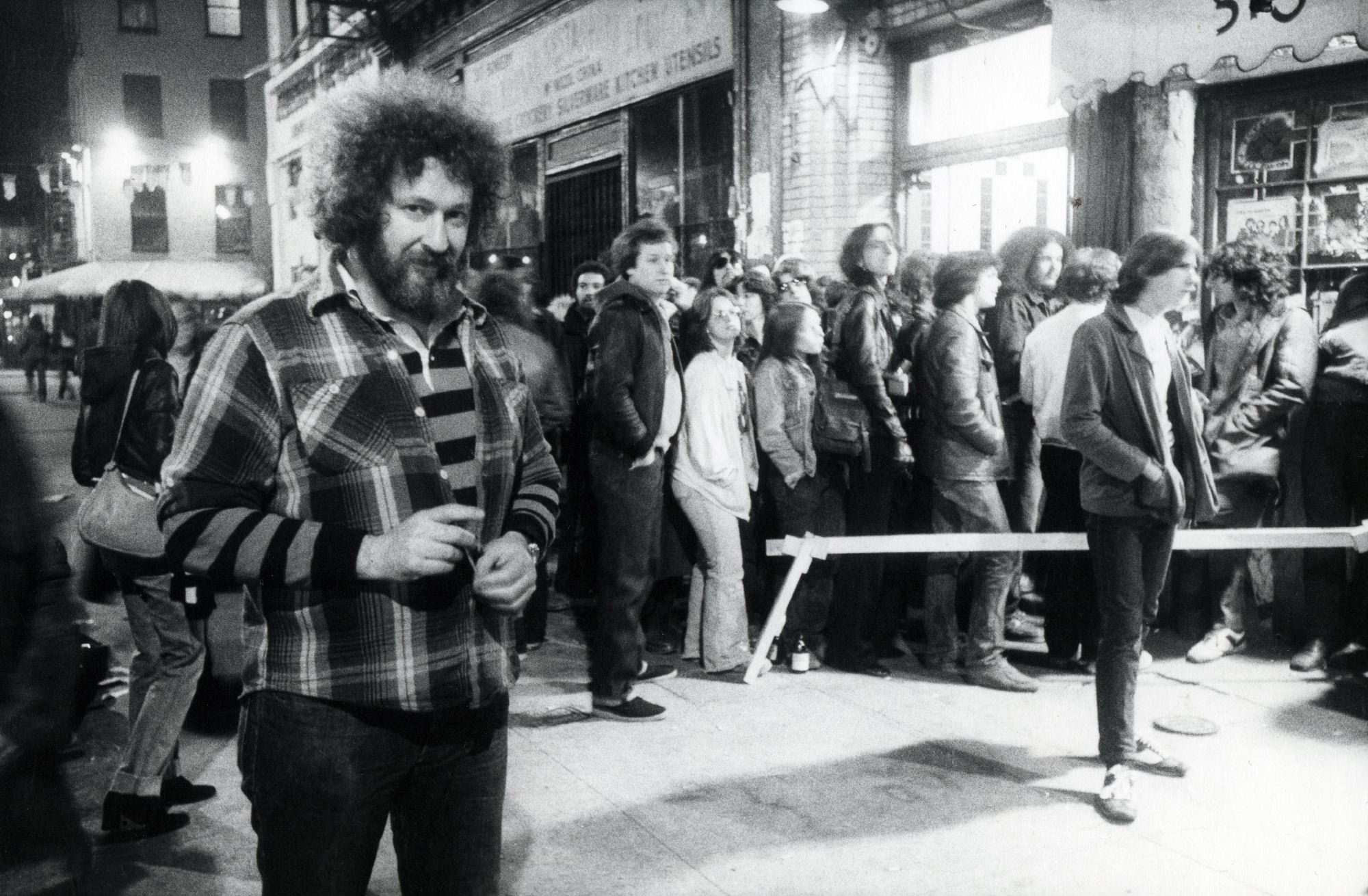

In 1976, Roberta greeted David Godlis (a.k.a. GODLIS) at the door and the two photographers became friends. After moving to New York from Boston, where GODLIS studied photography alongside Nan Goldin, he became fascinated with the underground scene at CBGB’s. It’s well documented in his book History is Made At Night, published just last year. “By the 70s people perceived New York as not a place they wanted to be. But I can tell you that everybody hanging out at CBGB’s in those days really wanted to be there,” he says. “They knew something was happening. You couldn’t not know it… You’re never guaranteed how long that’ll last and there was that feeling that you don’t want to miss it.”

i-D spoke to Roberta and Godlis, who still live on St. Marks to this day, to find out just what made photographing the iconic New York venue so special.

When did you start getting into photography?

Roberta Bayley: I took a few classes in high school, when I was 15 or 16, and learned about developing in my own darkroom and printing. I was fooling around with taking pictures, but it wasn’t a serious thing and I didn’t study it. I went to college at San Francisco State and the photography department was really popular. Everyone wanted to be a photographer. From the beginning, I started selling photos for almost no money. I didn’t see the point of taking pictures that I couldn’t sell, which was stupid in a way. Now, I could kill myself because I should’ve taken like ten thousand more pictures, especially in certain situations. I did a fair amount with Blondie, just because they were easy to photograph and I travelled with them. I’m glad I stopped when I did because when I look at Godlis, he just has thousands and thousands of rolls of film and I wouldn’t know what to do with that.

David Godlis: I bought a camera in 1970, when I was 18 or 19 — a Pentax Spotmatic. I’d seen Blow-Up, probably a couple years before, and it was a whole story about a cool photographer. So, I got a camera. It was just a hobby, I guess. I was taking English literature courses and thinking I wanted to be a writer, but from there, I went to the library and started taking out photography books. I wasn’t supposed to be taking photography courses, but I convinced the teacher that I wanted to learn how to be in a darkroom rather than send my pictures off to the drugstore and he let me stay. Then I went to Imageworks in Boston. I was definitely the guy who was doing the street photography. I did that in Boston and I was just like, I think I need to go out in the world and do this. Enough with school. So I headed to New York. It just so happened that New York was also where The Velvet Underground was from and when I got there, I found this scene kind of based on that.

How did you come to find CBGB’s?

RB: I came to New York in April 1974 from London, where I’d been living off and on for two or three years. I didn’t know anybody. I just came here. I got a one way ticket. One person had asked me, ‘What do you want to do here?’ You know, when you’re new everybody wants to show you around and so I said I wanted to see the New York Dolls. It turned out that this guy Dave not only had been their sound guy on the European tour, but he lived directly above Club 82, where the Dolls happened to be playing the next week. When I first saw David Johansen he was wearing a dress, high heels, and he had a bouffant wig on. I just started to get to know people on the scene. I saw Television at Max’s with Patti Smith. Not long after that I met Richard and we started a relationship. That was when Television was doing a residency at CBGB’s and so, Terry Ork, the manager, just said, ‘Can you sit on the door?’ And there would be 20 people there. Bands were looking for a place they could play on a regular basis, learn to perform in front of an audience, learn their craft. It makes sense if you think about it. It’s like The Beatles at The Cavern Club.

DG: It was pretty easy to see in The Village Voice that there was this strange place. I went down there thinking, this looks like a nice place to check out. The Bowery was pretty much empty back then. There was nothing happening except gas stations and bum hotels and, ‘this must be the place,’ — the place with the awning out front. I walked in and the first person I probably met was Roberta. New York had professional places, where bands with record contracts were playing, but CBGB’s seemed like something off the cuff, different. And that interested me. I had a day job as an assistant, but I always took my camera everywhere. I didn’t expect to take pictures. It wasn’t considered cool and artistic to take pictures of rock and roll stars and these weren’t rock and roll stars anyway, but it was something different. It was a scene.

What was it about the atmosphere of CBGB’s that made it such a great place to make photos?

RB: I took pictures a little bit of all the bands that I liked, but not very much else. I hardly have any pictures of Blondie there because it would be too crowded. That’s why I have good live pictures of the Ramones because there was no one there at the beginning. It was very early. The stage was right up to where the audience is. You knew. You just kind of had a feeling who the cool bands were and who the not cool bands were. And we liked a lot of people in the not cool bands. We just didn’t like their bands.

DG: I was a big fan of Robert Frank and his book, The Americans. It was like a touchstone for me. One picture I had in my mind, of a bunch of kids sitting around a jukebox in a candy store in the 1950s, and I kind of wanted to take a picture like that of the people hanging around CBGB’s. There was great subject matter, whether it was the way people looked and dressed, the way the place looked, there was always something every night. You’re peeing downstairs in the men’s room and you’re like, maybe I should be taking a picture of this? It was so easy and natural under the guise of being weird and strange, you know? If you could get over that it wasn’t really weird and strange, that it was just as natural as could be, that’s why everybody loved it. Hearing the Ramones didn’t sound like something crazy. It sounded like exactly what you wanted to hear and you wouldn’t hear it anywhere else.

When you were taking these photos did you ever think that you’d still be talking about them, so many years later?

RB: No. I mean, there was a real lull between the mid 80s to mid 90s when there was still an occasional article, but it was mostly ignored. It was right around the time of Please Kill Me coming out, that’s when I had my first gallery show. I’d never sold a print to anybody, ever. When did Nirvana get big? Early 90s? That helped too, that they were referencing those bands. But no, at the time, I didn’t think I’d be talking about it and I certainly didn’t think I’d be making money from it. Or that there’d be museum shows, or anything like that. And it’s still, as far as art goes and sales, it’s still kind of an uphill battle — rock photography.

DG: No. I thought I’d put out a book. But by the time 1980 rolled around and the Sex Pistols burnt out, Sid Vicious and Nancy’s death kind of tanked punk rock and turned it into New Wave, nobody wanted to do a book on those pictures. Then people started calling up because this scene back in the 70s, we think Nirvana is kind of influenced by. I’d been trying to convince people that it was an interesting scene! It became history, I guess. And at the same time, the thing that had never clearly been defined, which was exactly what happened at CBGB’s, that’s when Please Kill Me came out. And that cleared it up that this thing in New York had happened before this thing in England, and that they were both just as important. I think that everybody there wanted to last a long time. They wanted their music to last a long time, or whatever they were making. In people’s minds, what passes for nostalgia was simply what was going on down there. It was like a lightning bolt hit that place. There were so many ideas and so many interesting things happening there every night. When I was doing my book, all I had to do was put on the records — put on Television, put on Richard Hell — and it just comes right back.