The United States is in the midst of a student loan crisis. $1.7 trillion is owed, more often than not, by students that borrowed the money before they were able to legally drink or vote. It’s a decision that will too often haunt their adult lives. Especially art graduates, who are one of the most educated groups in the workforce yet have the highest rate of unemployment for any college major — when they do find work, it’s often unstable and underpaid.

In the lead up to the election, student debt has become a major talking point for Democrats, who see it as a matter of racial injustice. Students who were poor before going to university are likely to leave university with the largest debts. Last year, President Biden put forward a debt forgiveness plan that would alleviate some of the burden, but it was rejected by the Supreme Court in June — in a blow to up to 40 million borrowers. His second attempt is believed to be more legally robust, allowing the Department of Education to create repayment plans based on income. Like the English model, a single borrower earning under $30,000 would not have to make payments at all.

It’s an issue that is “affecting all individuals and their survival no matter the field of art they’re in,” says Kobe Wagstaff, a 26-year-old, self-taught photographer who grew up in a Mormon community in Utah. They recently travelled from coast to coast to document art school graduates, who were showing up for their craft despite predatory loan practices. Kobe was inspired by a conversation they had with a friend whose career had recently taken off — the artist was represented by a prestigious gallery, selling to celebrities, etc. — but feared she would never be able to pay off her loans. Reaching out to filmmakers, visual artists and photographers in their extended queer community, Kobe’s aim was “not to victimise them in any way but to highlight their practice, highlight who they are as individuals and to elevate them, immortalising this time in their life in photographs”.

In the US in 2021, the arts brought in almost $1 trillion to the economy, while £109 billion was contributed in the UK, however, the field fails to offer the financial security of a corporate job. While students shell out nearly $60,000 a year for an arts education in the US, they are rarely remunerated. “When you’re an artist you are fully encompassed in your work,” Kobe says. “It’s still a service and providing value. I find it interesting that our culture devalues that, but still expects these individuals to pay the same amount [for schooling] as a person that’s going the more traditional route.”

They may have the odds stacked against them, but the artists that Kobe has photographed — Andi Carter, Juan Lopez, Amina Cruz, Nande Walters, and Sterling Hedges — “transcend the anxiety, throwing it all into their art”. They use art to try and make sense of the world, offer a critical perspective of the human condition and to make others feel something deeply. Here, we asked them about their practice and the importance of democratising an arts education.

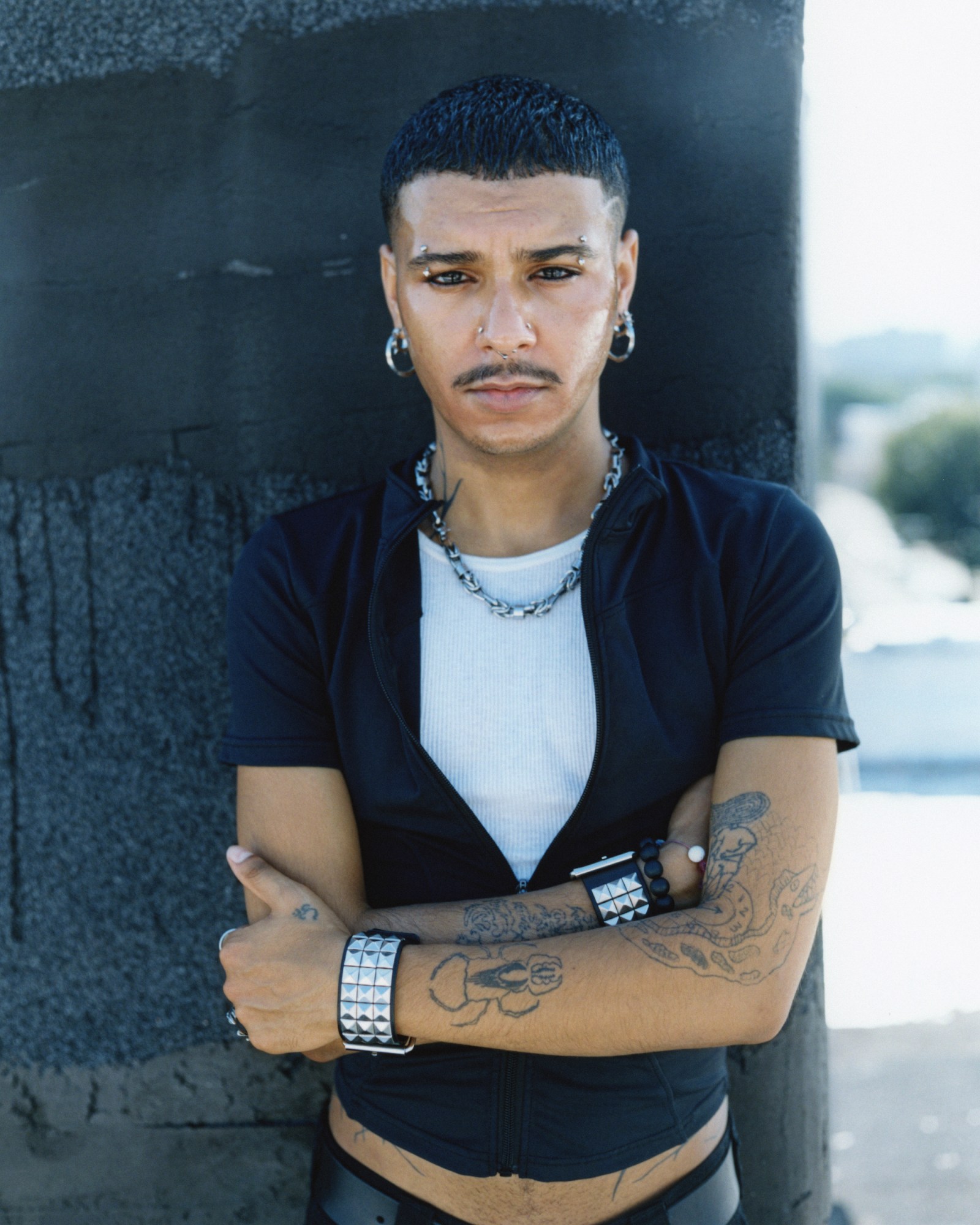

Andi Carter

Graphic Design and Visual Arts, University of Greenwich, London

Where did you grow up?

The Inland Empire. It’s about 40 to 50 minutes away from LA and much more quiet. My community, at least, was mostly Latinx people. My whole family is Mexican. And as an area, it’s lower middle class.

How did your family feel about you pursuing an arts education?

If I’m being 100% real, it took a lot of persuading. I went to an all boys Catholic high school for a minute. I was at my wit’s end. I had to convince my parents to let me transfer to an art school, where I ended up completing high school. After that my parents were just like, this bitch is kind of gonna do what they want to do.

What made you choose the UK for university?

The cost of schooling in the UK is a bit cheaper than it is here. For any art programmes, it would have been basically $30,000 every single year in the UK and over here it’s $50-60,000. If I wanted to go to a prestigious art school, it would be upwards of $90,000 yearly.

Did you take out loans?

I did. I took out $36,000 of student loans. I’m slowly paying that back, but it’s not easy. Luckily, through my transition I’ve found really beautiful family and friends that really support me when I don’t have enough.

Did you feel like it was worthwhile attending art school?

I think about being in school every single day to be quite honest. It helps you stick to something. It pushes you to make things even when you don’t want to be making things. I think that everyone should go to school. The only thing that will make it better would be to make it more accessible to people and obviously, that has to do with money. It puts you back before you’ve even started. But I love art, and I’m gonna be making this shit until I die.

Tell me about your art practice now.

The pandemic was a really crazy time, I was figuring out a lot of things about myself, my presentation and who I was, and what I’m doing. I focused a lot on figures and bodies, but post-pandemic, I started to transition and realised that I can have a form of art through myself, and market myself that way too. I’m working on a couple different projects using sounds I’ve made with a digital synthesiser. They’re more emotive and spatial rather than something that’s supposed to be danced at or to, in terms of musicality. I’m hoping to release them in the upcoming year backed with visuals that I’ve been cooking up on my laptop.

Does having student loan debt hanging over you affect your creativity?

Absolutely, because at a point I was creating for me, but now I feel like I have to make money. Monetisation was never the goal. I’ve had to shift focus to creating things that will hold me over to the next month.

How do you thrive despite it?

Trying to thrive despite adversity is definitely not an easy thing, but I think being a little delusional, honestly, helps so much. I don’t know if it’s because I’m a Pisces or what, but sometimes when I get super stressed out I’ll have to throw my hands up and give it to the universe. I think it’s all about how and where you channel your energy.

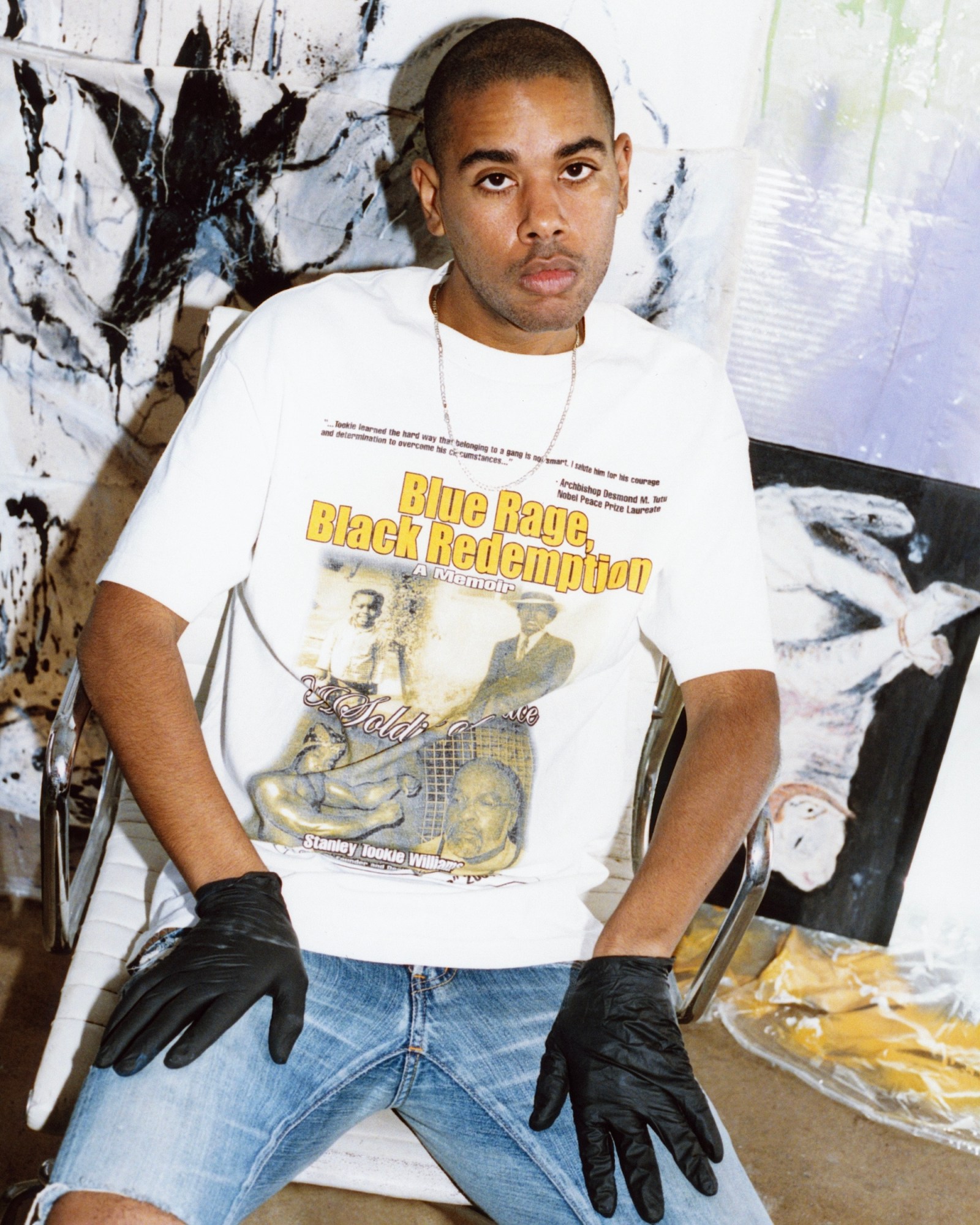

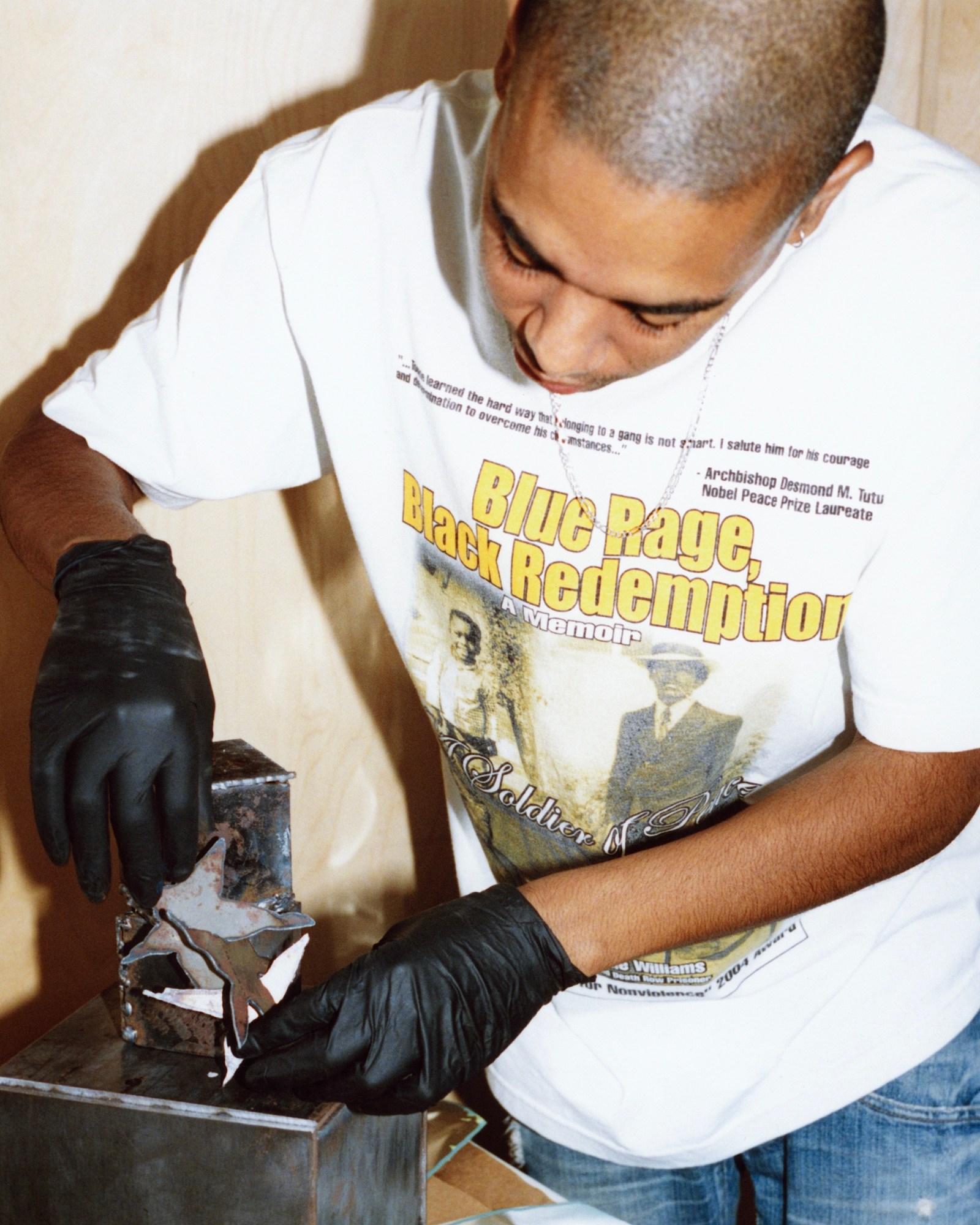

Juan Lopez

Film, Bennington College

What are you studying at Bennington College?

At the school I go to you get to design your own major, so my thesis statement is a study of the visual aesthetics of violence and Black rage through film. Initially, I applied for college to be a poet, but when I got to school it seemed very whitewashed so I made the switch to film.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in Boston, but I was born in Newark and lived in New York City until I was seven. Moving to Bennington College was a bit of an adjustment. Vermont is one of the whitest states in the country whereas I’m Black and non-binary. The school is situated in a town that is 96% white and it’s also filled with older people. It’s a divide — not just racially, but generationally as well.

Tell me about your practice.

I first started thinking about James Baldwin‘s quote: ‘To be a conscious Black person in the United States is to be in a constant state of rage.’ That’s something I’ve always felt, but it was putting words to it when I got to college because it was the first time I was in an environment when there weren’t other people that looked like me. I’ve realised how I’m angry and how my Blackness pairs up with my anger. Then it was: how do I make work that can express that through a visual sense.

How have you managed to distil that?

For me, it was through reappropriating violence in a way that isn’t recreating the violence in its original form. I wanted to make work that is very visually influenced by BDSM and kink practices as a way of queering the violence that I’m talking about.

Can you talk to me about the financial burden you’ve taken on to attend college?

I only applied to Bennington and Howard University, but Bennington gave me a scholarship. The decision to go to this school was primarily a financial decision. Even with the scholarship, I’m still in debt.

Do you feel like it’s worthwhile?

In some ways, I say yes because I hadn’t touched a camera until I went to school here. The skills and resources have helped me think about my work, but at the same time, I thought I would get a completely different type of education from undergrad than I’ve received. I thought that you would make connections, and they help you try to get into a gallery, which is where I’m trying to be placed. But that’s not what you’re getting.

Do you think how much art school costs affects how the industry ends up looking?

I think one of the first things I noticed after coming here was just the amount of wealth that a lot of these people have. I had never experienced or seen people this wealthy. It’s really interesting how people are placed into this art canon, but it’s almost like nepotism or privilege to pay for your spot and then there are the few people who are on huge scholarships working jobs at the dining hall. It’s just privilege creating more privilege.

Has going to art school made you look at class and wealth in a different way?

I see the way that wealth is protected and kept around certain groups of people. Overall, I think the most important thing is to make art education more accessible. I have so many friends that have had to drop out because the financial burden is so much. You have these really talented pupils who have to step away from an education. Everybody has that potential and when you gatekeep it, it’s a shame. Education is a right not a privilege, but that’s not how the system works here.

Amina Cruz

BFA Parsons School of Design, MFA in photography UCLA

What made you go back to grad school?

I wanted to have more access. Technology had changed from when I was in undergrad and I was interested in building a community and meeting like-minded people. The other reason is that I never saw people like myself on TV or in magazines, and I realised I can’t complain if I’m not a part of the conversation.

Are you glad that you went?

I’m happy that I went. Having an education for four years around art, especially photography, was amazing. But the thing was that, at the time — I’m a little bit older — they just assumed everyone was wealthy. The tuition was massive, then it was living in New York and on top of that it was supplies like film and printing costs, buying specific photo paper for the dark room, or for digital printing. If you wanted to photograph people you’d have to pay them a little bit or at least buy them lunch. The school doesn’t cover any of that.

What was it like being a person of colour at Parsons?

There were a small amount of people of colour in my year, but by our second year I was one of the only people left. The entire time I was at Parsons I didn’t have any poc instructors.

There was this one moment where I had to go to financial aid and the guy there was like ‘call your mum now, you have to pay this bill or we will kick you out of school’. I was living in a dorm, so he threatened to kick me out onto the street. My mum was nervous and told me to take out a student loan so I could stay in school, but at 21 you don’t realise what a student loan really means. They make you read the information that’s like ‘this will follow you forever and it might affect you buying a house’, but you don’t understand any of that when you’re a young adult.

Has it affected you in any of those ways?

Greatly. It’s a constant worry and stress. Even if I start making a little bit of money then the payments will have to go up, so I can never get ahead. I believe that you better yourself through education, you get to change your situation, but that’s not true. I come from a working class background — I’m the first to go to college. I’m the first to get a bachelors. The first to get a masters.

Do you feel like school has helped you?

Grad school allowed me to see the importance of what I was doing. It’s giving me a connection to a larger community and a larger audience. Kids in the middle of the country message me on Instagram saying they’ve never seen queer people photographed like this before and how important that is for them. Living in New York and LA, I forget that a community that’s ‘other’ can be so hard to navigate when you live in smaller towns, so it’s important to keep making this kind of art.

How would you describe your practice?

It’s documentary and I’m stretching it to be a little more narrative and fine art. I just had my first solo show and I’m working on a book that will be all the queer subcultures that I photograph.

That’s amazing.

Even through all of this, I love that I show up for this need to create. My goal and main motivation is to create I sacrifice for that.

Nande Walters

Film and Video, Pratt Institute

Have you always wanted to be a filmmaker?

I’ve always been an artist: drawing, painting and stuff. I was an avid reader, so around 8th grade, I wanted to be a writer and then that snowballed into wanting to do filmmaking. I especially wanted to leave Florida.

Do you feel like going to Pratt was imperative for what you’re doing now?

Reflecting on the few months since I’ve been out of school, I definitely appreciate my experience of having the name attached — which I think is a big part of why we all choose to go into this debt. For me, wanting to do film, it was between California and New York and I’m thankful I picked New York. It’s definitely more artistic in terms of filmmaking and I wouldn’t be the person or the artist I am if I hadn’t chosen to go to Pratt.

How did the pandemic shift your practice?

In that spring semester, when I did have some films — one that I started before everything shut down — I was able to finish it in my home. It was about my relationship to my hair. I used old pictures and found materials, but I did film myself in New York and then in Florida. I’m primarily interested in making documentaries and diaristic films. I love experimental filmmaking and personal stories, whether they’re about me or someone else. I love getting to know people through the camera and editing.

What are you working on right now?

I’m a curatorial intern at the Studio Museum in Harlem until December. Then in January, I’ll start my masters in library science at Queens College. I’ve been prioritising rest since graduating, especially after working on my last film, Soon Come Back, for over a year. I also recently finished a film called Something That Means Nothing (October), a diaristic film about me in my apartment in October 2021.

What does making art mean to you?

Art is definitely a form of expression for me. It’s a way to get what’s inside of my outside, whether other people see it or not. I’ve been creative my whole life and it’s very rewarding to continue to do so as an adult in school and work.

Can you tell me about the debt you got into through studying?

Thankfully, me and my family were able to qualify through FAFSA (Free Application for Federal Student Aid) for a parent plus loan, so my loans are a couple of thousand dollars per semester and my dad has the burden of the loans of about $200,000. It’s a lot, and it’s something that I’m coming to terms with now, and also planning to go back to school. It’s more of a tangible thing to me now than when I was 18, trying to convince my parents that it will be worth it.

How are you managing?

I’ve been given the Creatives Rebuild New York’s Guaranteed Income for Artists grant for the past 18 months. It’s an incredible new program for marginalised artists in New York state, and I wouldn’t have the financial stability or time to have done what I’ve done in the past year and half without it.

Sterling Hedges

MFA Art and Technology, California Institute of the Arts

Why did you choose to do a masters at Cal Arts?

I chose to attend Cal Arts primarily because of the art and technology program. My conceptual focus points to technology’s accelerationist impact on culture and the subjective experience.

Can you tell me about your practice?

I was focused primarily on video art and performance, but recently my practice has shifted to encompass more painting and sculpture. Some of my current paintings are experimentations in abstraction, others are investigations of Old Master painters. A through line into my previous works is a tie to the pastoral; copoiesis, or a coming into being together. I attempt to pause within moments of human entanglement with the earth, the landscape and agricultural technologies.

What does making art mean to you?

Making art provides an opportunity to breathe, to be with myself, to be with others, to express myself beyond words and as vividly as an embodied feeling.

How much did art school cost and would you say it was worth it?

With a scholarship, the cost was $50,000. I’m not sure I can assign a worth to that time. Was it beneficial to hold space for myself to focus on my practice and learn from professors and peers? Yes. Do I believe monetarily my career opportunities have reflected this? No. That being said, I didn’t expect to leave an institution with any more than a piece of paper and lots of debt.

Has it hindered you in any way?

If I crunch the numbers or think amount it too much, the weight of it starts to feel so heavy and insurmountable, otherwise there’s more of a passive sense of sinking further into debt. Compounding this emotional toll is a sense that I’ll die with this debt.

How are you thriving in the face of this adversity?

While I wouldn’t exactly say thriving, I’m appreciative of my friends and peers for seeing me and encouraging me to continue to produce work.

Credits

Photography Kobe Wagtaff