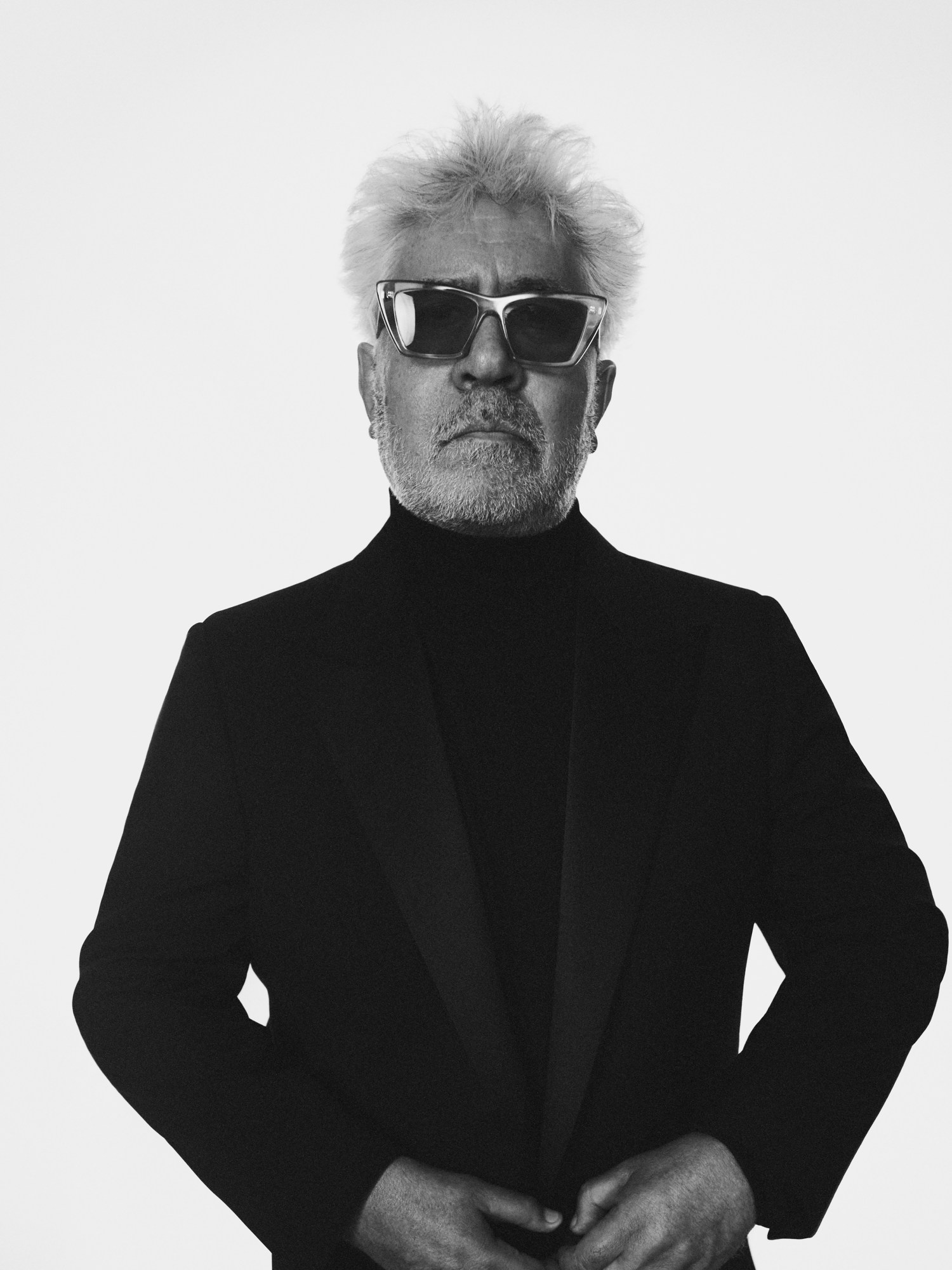

Pedro Almodóvar speaks to me from the desk holding all his secrets. It’s placed in the centre of his office, drenched in Madrid’s sunlight from all angles. The Oscar-winning director – known for films like All About My Mother, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and 2021’s Parallel Mothers, and his ongoing collaborations with actors like Penélope Cruz, Antonio Banderas and Rossy de Palma, for whom he’s created some of their best work – sits and writes here on his computer. “It has not only the movies that I’ve done but also the movies I haven’t done yet,” he says. If he has any secrets, he says, “They will be around here somewhere”.

It’s also the desk where his latest film started life: just 15 lines on a page, an exchange between two older gay lovers speaking to each other across a cavernous emotional void after years spent apart. One is besotted, ready to rekindle their long-lost romance; the other is in deep denial of what once was. Things often come to Pedro in miniature form like this. “Sometimes I write set pieces just for the pleasure of doing it,” he says. “I keep it on the computer, and many of them afterwards find a place in a movie.” But in the case of Strange Way of Life, it was a conversation with Saint Laurent’s creative director Anthony Vaccarello that prompted him to revisit this scenario. After their meeting, “I thought to write about how these two characters reached that moment and what comes afterwards,” he says. “Of course, this could have been a feature, but I was interested in making the short film because, in some ways, it’s very abstract. I isolate these two characters and force them to deal with their contradictions in a very personal way.”

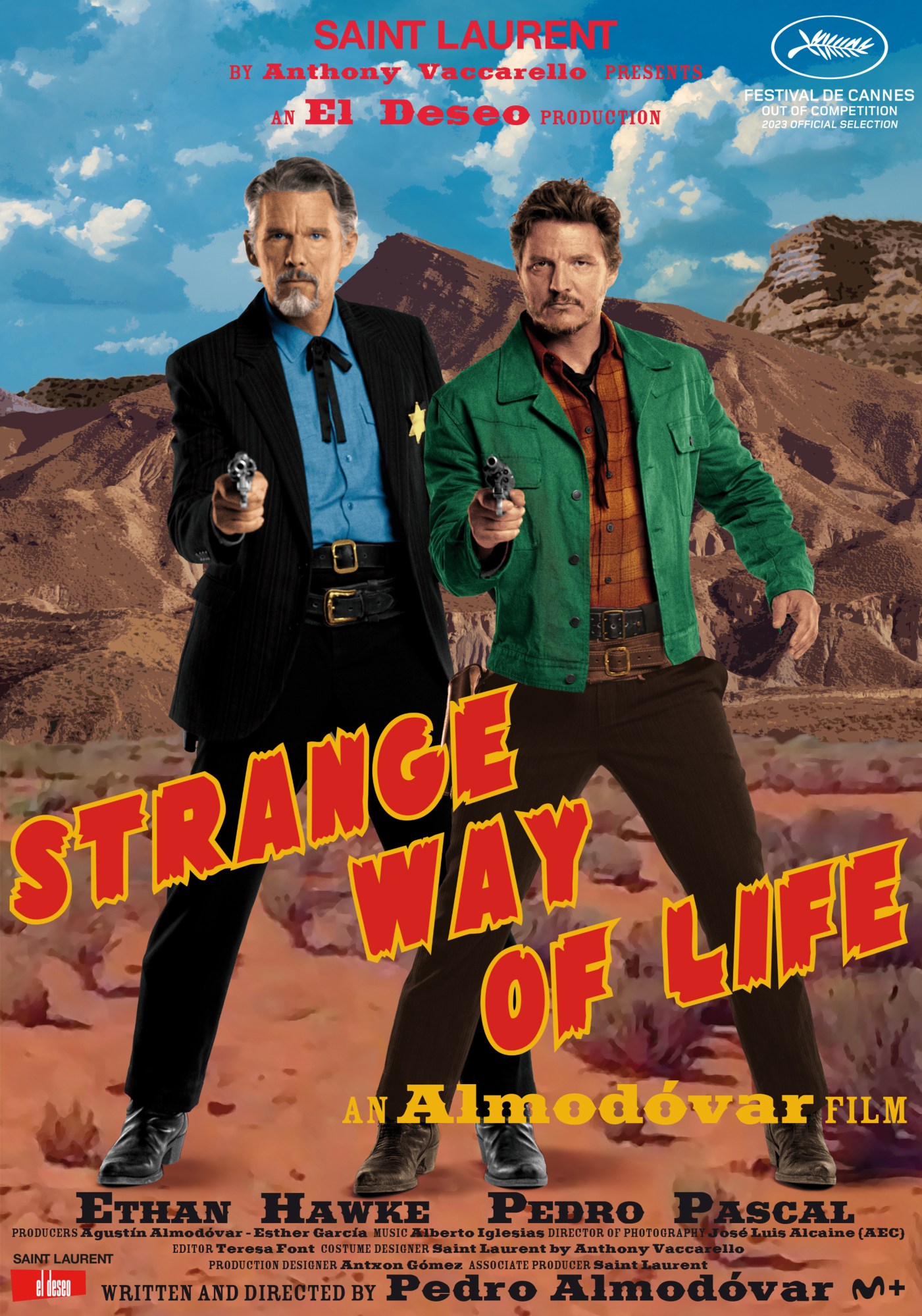

Pedro’s second English-language film following 2020’s Tilda Swinton-starring short The Human Voice, Strange Way of Life is the first film from Saint Laurent’s film production company, an idea pioneered by the house’s film-obsessed creative director. Joining Pedro over the next few years will be the likes of David Cronenberg, Jim Jarmusch, Wong Kar-wai, Gaspar Noé and Paolo Sorrentino. This, Anthony says, “is a way for me not to thank them, because they don’t need that, but to acknowledge the way in which their work has shaped me.”

The Saint Laurent touch is important behind the scenes, but, as Anthony wishes – “I like to let directors be free, and I don’t want our films to be overly commercial” – light on the film’s surface. Strange Way is a moving, deeply romantic western made the way Pedro wants to see it. In it, Pedro Pascal plays Silva, a man who arrives in a small village on horseback to greet an old lover Jake, the town sheriff, played by Ethan Hawke. 25 years have passed since they last spent time together – a heady, erotic scene involving bullet-pierced barrels of wine and passionate kissing highlights their shared past – but their meeting now isn’t so harmonious. Something will have to be dealt with in order for their love to return to how it once was.

There are a handful of background characters (Elité’s Manu Rios, whom Pedro calls “angelic”, has a brief appearance as a guitar-playing boy lip-syncing to the song that gives the film its title), but Silva and Jake are at its centre. The director says it didn’t take much to convince Pedro (Pascal, that is) and Ethan to come on board. “From the very first moment they read the script, they were interested and wanted to be involved,” he says. “I was very lucky that they were both willing to do whatever I asked of them.”

Actors trust Pedro because of the places he takes them as performers. An admiration for the way he does that with women specifically was what drew Anthony Vaccarello to his work. He “highlight[s] their individuality and strength,” Anthony says of the typical Almodóvar woman. “I think in the film we did together he treats men the same way… giv[ing] them space to express a complex range of human emotions.”

Pedro says he is interested in “how we explore the soul of the human being, talking about desire”. But there’s something interesting about men, particularly men like Silva and Jake, who exist in a setting like this. There is so much to say and yet so few ways in which they know how to say it, out of fear of judgement or retribution. “It’s all around us in culture,” Pedro says. “In elite sports, amongst bullfighters.” It’s baffling to him that these ‘hypermasculine’ industries seem caught up in the idea of pushing back against homosexuality when “the US has states that are trying to bar transgender people from participating in politics or entering certain spaces and are struggling with issues around abortion. I’m always perplexed by the fact we struggle so much with issues of sexuality when there are much bigger problems in the world.” Films like Strange Way of Life play a part in the pushback against the pushback.

When Strange Way of Life was announced, it instantly reignited the old rumours that Pedro was one of the filmmakers lined up to direct Brokeback Mountain – another queer Western. He now confirms that the longstanding rumour was true. When he was approached by the film’s producers, “I already knew the Annie Proulx short story, [and it] was full of physicality – they start having sex like animals, looking for some warmth because it was so cold,” he says. That was absent in the script he read. “I thought that if I was to do a version of that short story, it would have more sex scenes.” He shrugs it off. “But that was my point of view. I think [the film’s director] Ang Lee made a wonderful work.”

Consequently, it was assumed that Strange Way of Life would be the kind of carnal Western he had hoped for with Brokeback. Instead, the opposite is true: Strange Way isn’t chaste – there is nudity, and at one point, Silva spits the word “cum” with such throaty disdain that the sound of it is shocking in itself – but the film isn’t gratuitous either. “There is a lot of physicality,” Pedro says, “but it’s not explicit. It was more interesting that the words were more naked than the bodies.” He told his actors prior to the shoot that the sex scene at its centre, “the very orgiastic night, would be treated elliptically”. All of its sexual energy stems from the glances they share and the suspended silence in the air, an atmosphere that feels liable to implode.

Every inch of this world is, as is Pedro’s trade mark, precise and purpose-built, but this is a rare example of the filmmaker abandoning what he calls the “anachronic” nature of his work set in Spain and branching out into a more fantastical world. On the walls of Jake’s home are paintings by Georgia O’Keeffe (“She lived for decades in New Mexico”) and Maynard Dixon (“the first American artist to paint cowboys and [Native Americans]”), as well as photographs of actors like Lillie Langtry, a socialite turned stage actor present in early Western movies.

Anthony designed the film’s costumes. “Working on the costumes… is a good way for me to enter into someone else’s idea. To develop a character that was not part of me, that didn’t come from my desire,” he says. Together, the director and designer pushed against Pedro’s traditional time-specific styles and used Western movies – rather than the period in which they’re set – as their references. “As a European, [silent Westerns] were my introduction both to the Western as a genre and to American history, right?” Pedro says. Anthony started by sourcing clothes from the era, like the underwear, but “neither he nor I were interested in it,” Pedro says. “As a European, it made more sense to reference the West how we came to know it: through cinema.”

The delicious, emerald green jacket Silva wears, for example, was inspired by one worn by James Stewart in one of his many Western collaborations with Anthony Mann. There were compromises: “I always wanted a little more colour than Anthony because that’s my style,” Pedro says, winking.

When we speak, Strange Way of Life is weeks away from meeting its first public audience at the Cannes Film Festival. It’s Pedro’s 41st film as a director. 2024 will mark the 50th anniversary of his first short film, Two Whores, or a Love Story That Ends in a Wedding, about a sex worker whose clients, negatively impacted by the Free Love movement, are magically conjured by a fairy.

His work has become a little more grounded – if still thematically anarchic considering the conservative society they enter today – as decades pass, but his ambitions, at 73, are not shrinking. He’s been thinking of the southern Spanish musicals, shaped by folklore, that were made between the 1930s and 50s. “It’s a genre that hasn’t much left Spain except for South America,” he says. “It would be interesting for me to approach that genre but from a more contemporary point of view.” He calls them excitedly: “Very kitsch! Very kitsch!”

He’s been wed to the familiar world of Madrid and its outskirts for a while, save for the queer family drama All About My Mother (famously shot in Barcelona because the “transsexual people I knew were [there]”, he says). But there’s also an untapped intrigue for pastures new. The places he’d like to make films in future are extensive: India (“Despite the cultural differences, the colour palette is interesting to me. It almost feels like pop”), the Caribbean, Cuba, Italy’s Amalfi Coast (“Their culture is similar to Spanish”) and New York City are just a handful.

It’s likely that the stories Pedro Almodóvar will tell in these places exist in some form already, nestled somewhere in his desk of secrets. “This is part of the adventure,” he says, leaning forward in his chair. “The good thing is I like to write, [but] I don’t feel like I must make something [from that writing] immediately.” Those 15 lines of Strange Way of Life are proof of his artistic policy.

“I keep them,” he says. “And sometimes, I’ll find the right place for them.”

‘Strange Way of Life’ had its world premiere at the Cannes Film Festival. It will be released globally later in 2023.