On the cusp of her tenth birthday, Virginia Turbett sobbed into her pillows for three nights in a row, devastated her parents refused to allow her to attend the Monkees perform at Wembley in July 1967. As she entered adolescence, Virginia’s tastes began to mature, her record collection expanding to include new albums from Leonard Cohen, Santana and The Doors.

During the summer of 1971, Virginia met three guys from Bristol, who played a cassette of David Bowie’s fourth album, Hunky Dory, in a tent on a North Cornwall clifftop. Transformed, Virginia returned from holiday to her home in rural West Sussex, ordered the entire Bowie back catalogue and pre-ordered Ziggy Stardust. Every Thursday morning, she hopped off the school bus and dashed to the local newsstand to pick up the latest copy of NME.

“That was my Bible,” Virginia says. “I would read it from cover to cover and write down who was touring, where, and when the tickets were going on sale.” She saved her babysitting money and skipped school to wait in line for front-row seats to see artists like Lou Reed, Alex Harvey, Captain Beefheart, as well as her idol Bowie. Then, on July 3, 1973, Virginia stood in the audience as Bowie announced he had killed Ziggy to a devastated crowd at the Hammersmith. It was the first historic moment she would witness amid a sea of fans who unwittingly came together to share their favourite’s swan song.

She brought that same approach to photography when a friend asked her to photograph the Sex Pistols recording “Pretty Vacant” for Slash magazine in 1977. “I didn’t know what I was doing,” Virginia says. “I didn’t know how to change the film and ad to go to a camera shot on Tottenham Court Road to get a man to do it for me. But it was punk. Everyone could be in a band, be a photographer, or a writer. We didn’t have to be massively successful or earn lots of money because that didn’t exist.”

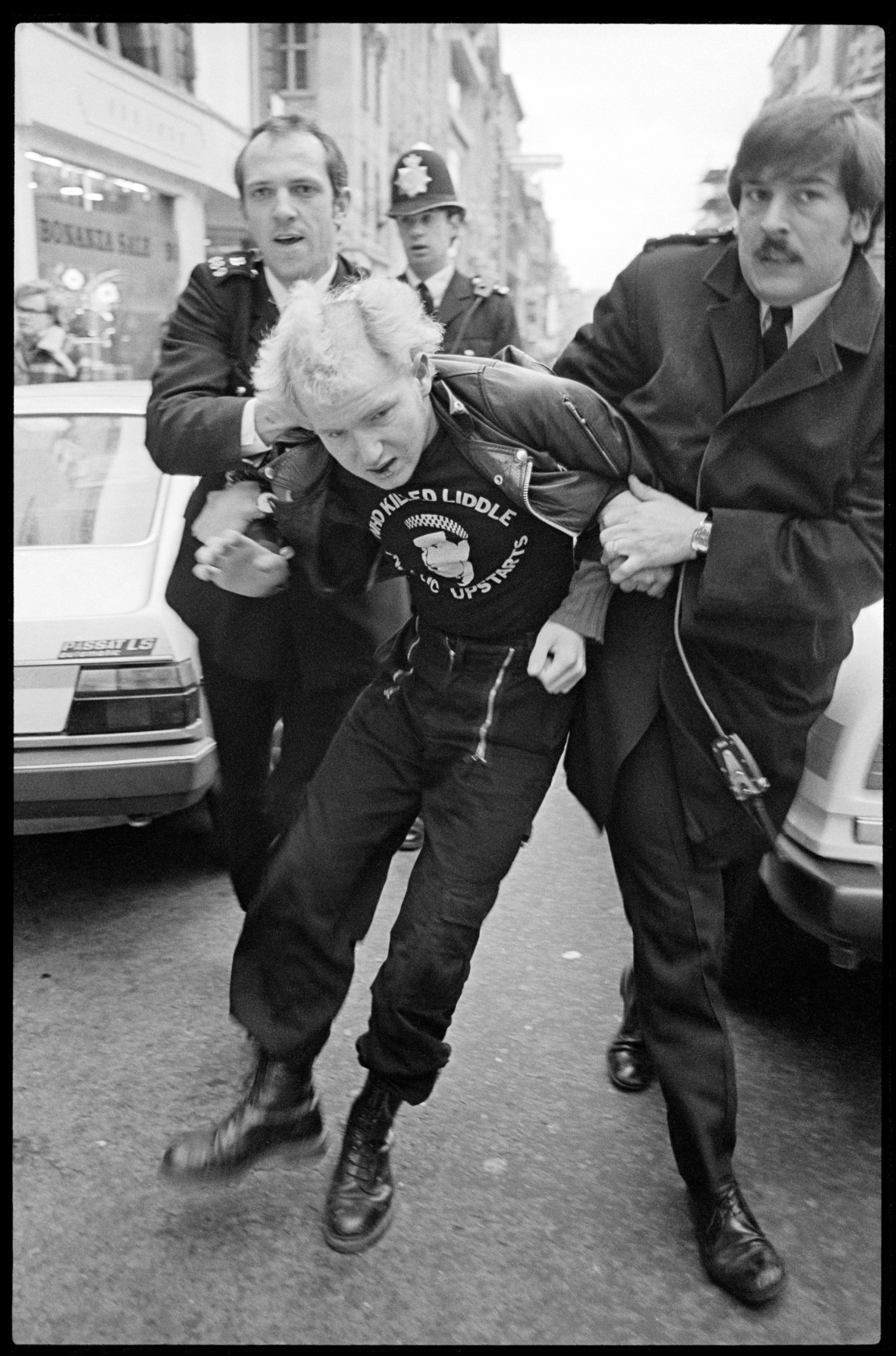

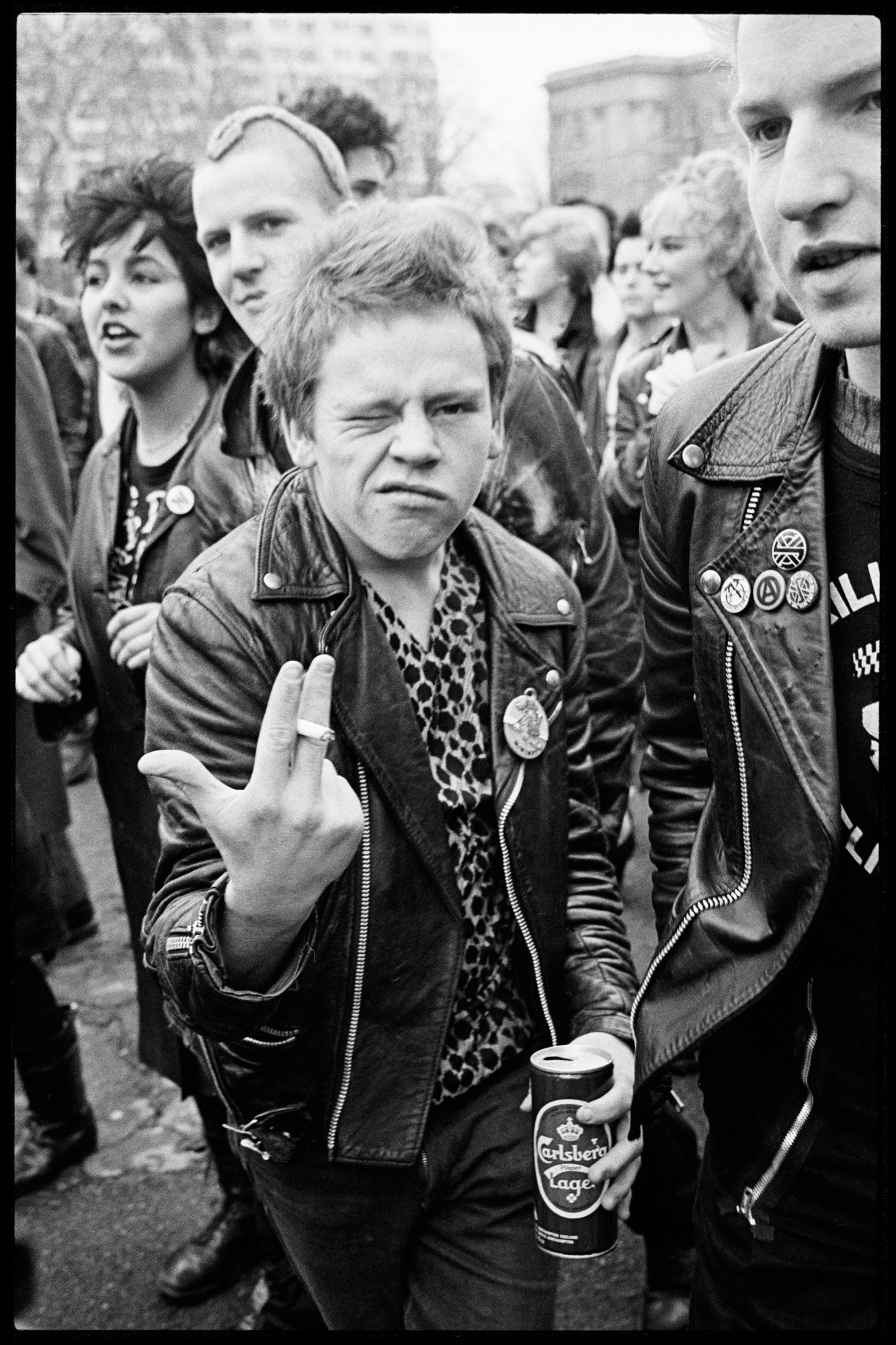

Unfettered by careerism, Virginia road-tripped across the US with her boyfriend for nearly a year, catching the Sex Pistols’ final concert in San Francisco. After returning home, she moved to London and launched her freelance photojournalism career covering music for Sounds and news for a socialist newspaper that brought her face to face with issues facing the working class at the time.

“I did stories on poverty, housing, the riots and the National Front, which was doing quite well electorally at the time, and I was travelling up and down the country for Sounds,” Virginia says. “Every city had an incredible scene going on. You’d go to Edinburgh, Glasgow or Leeds, and all the bands knew each other. They also had a local label that they were under.”

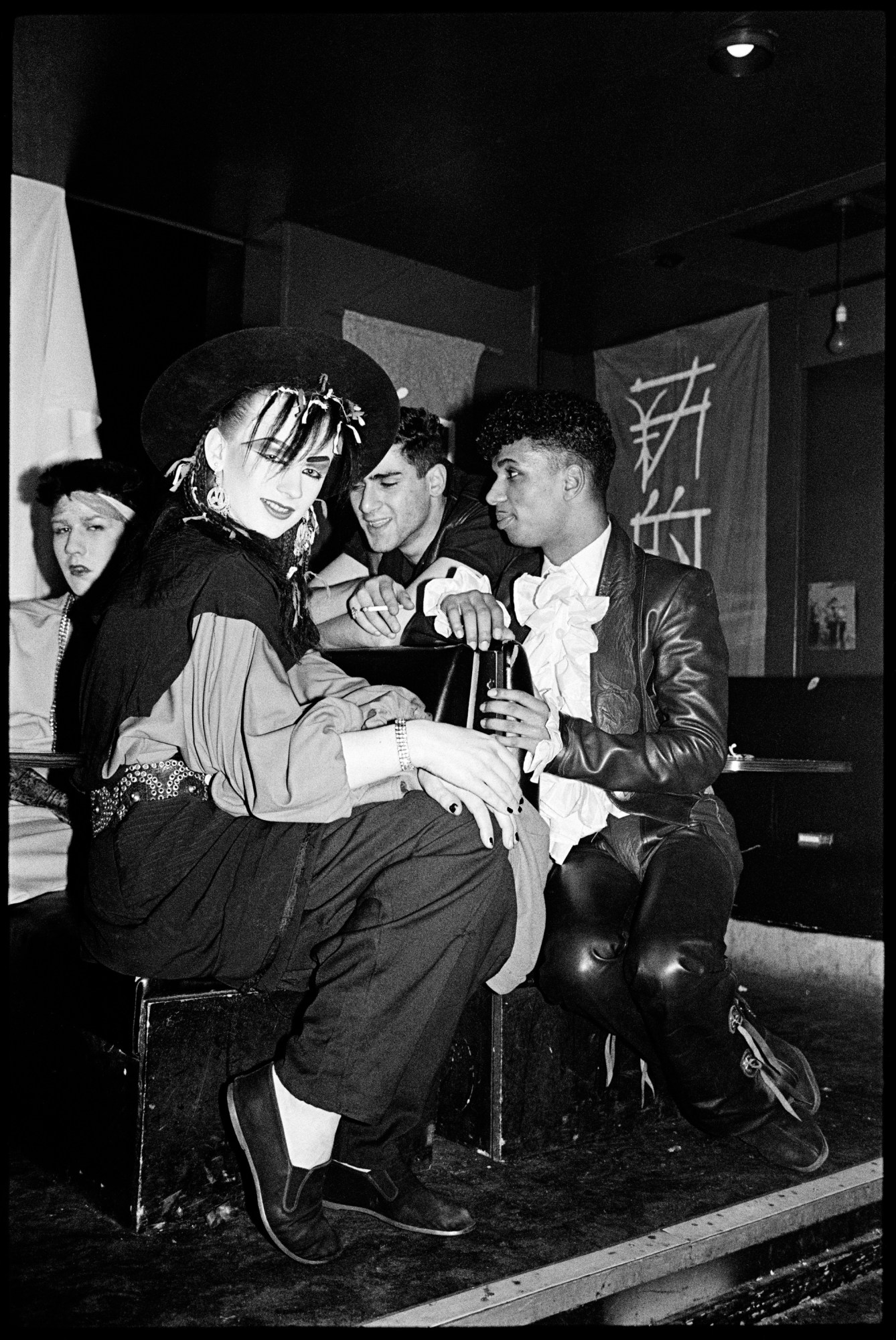

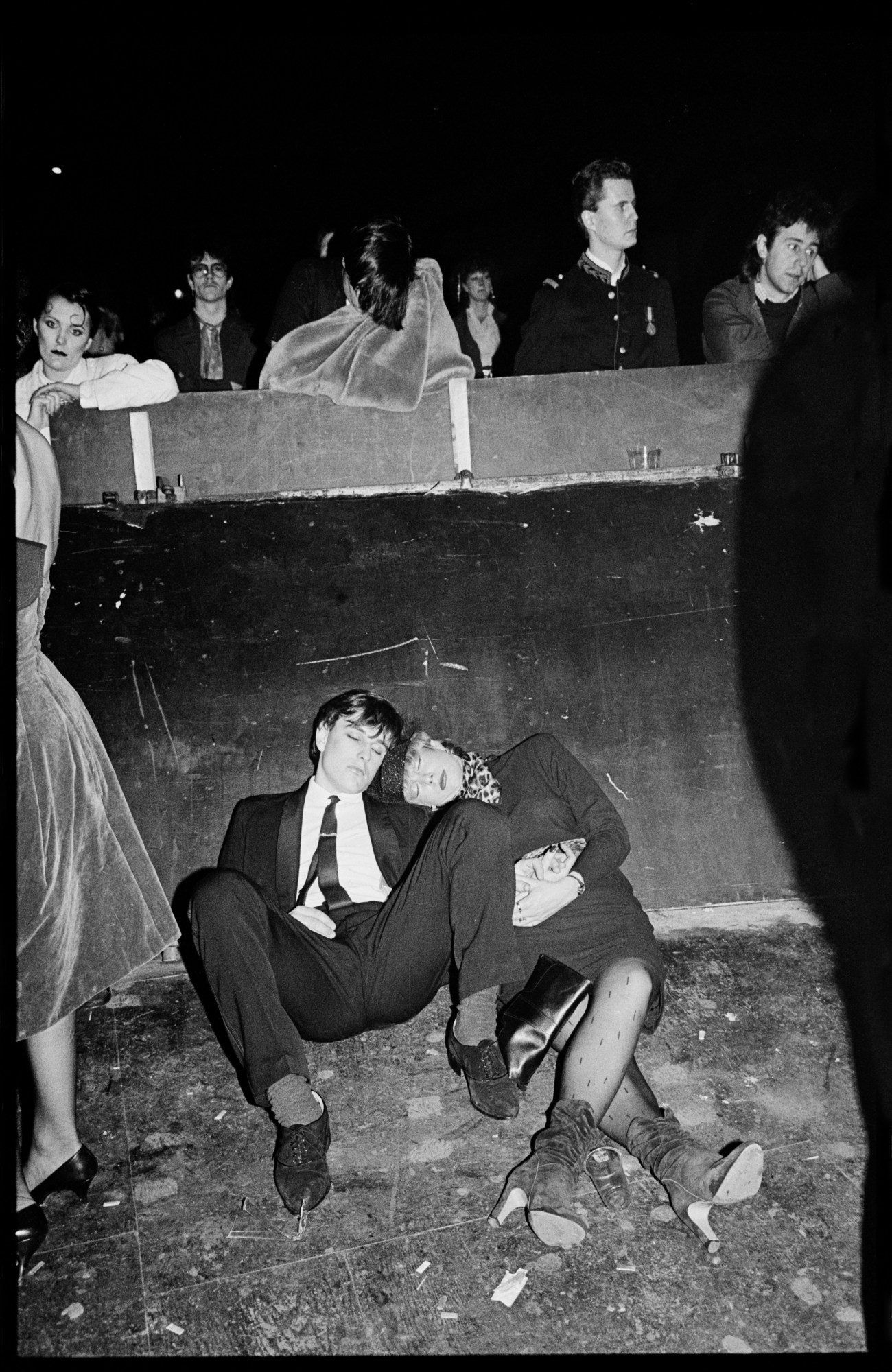

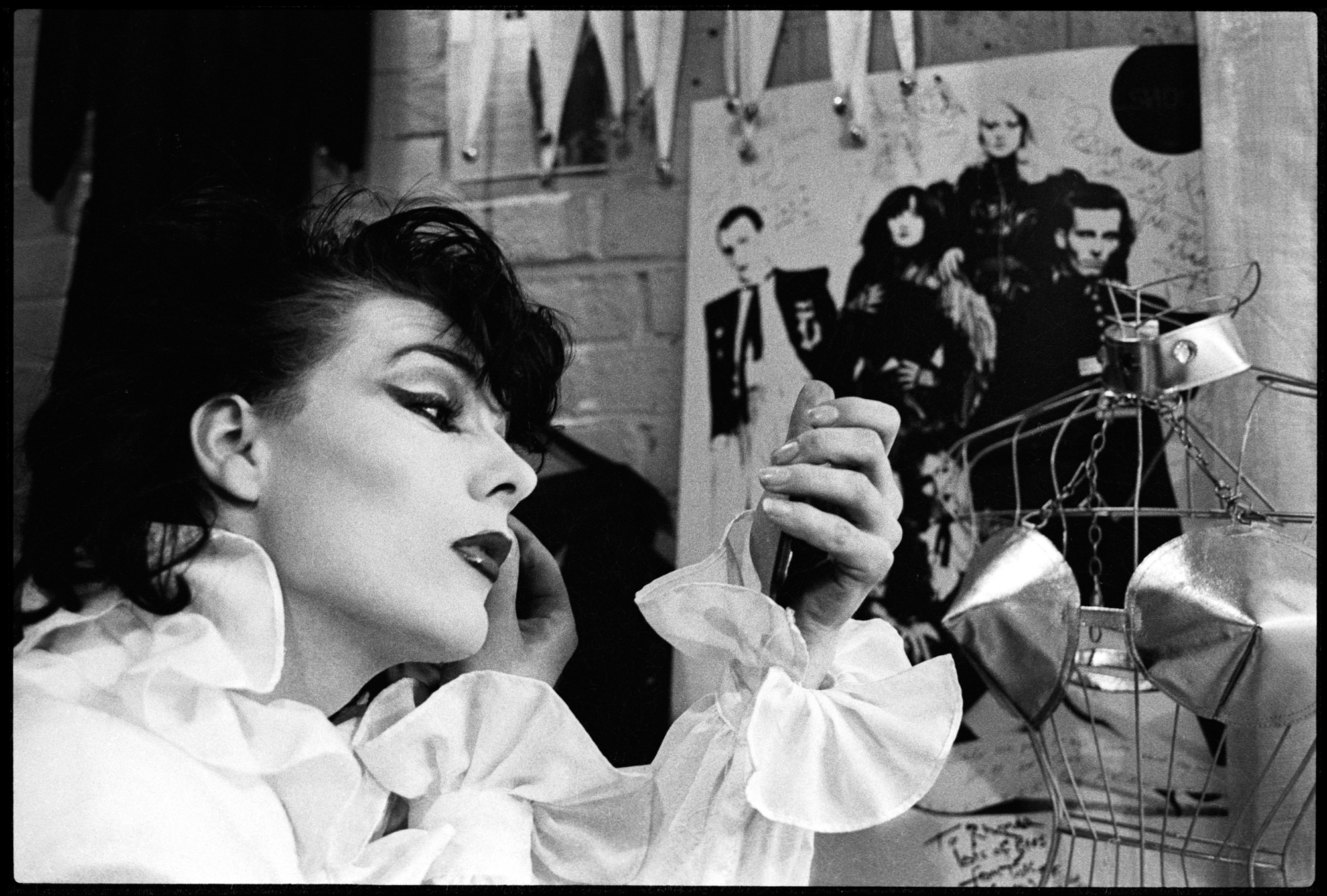

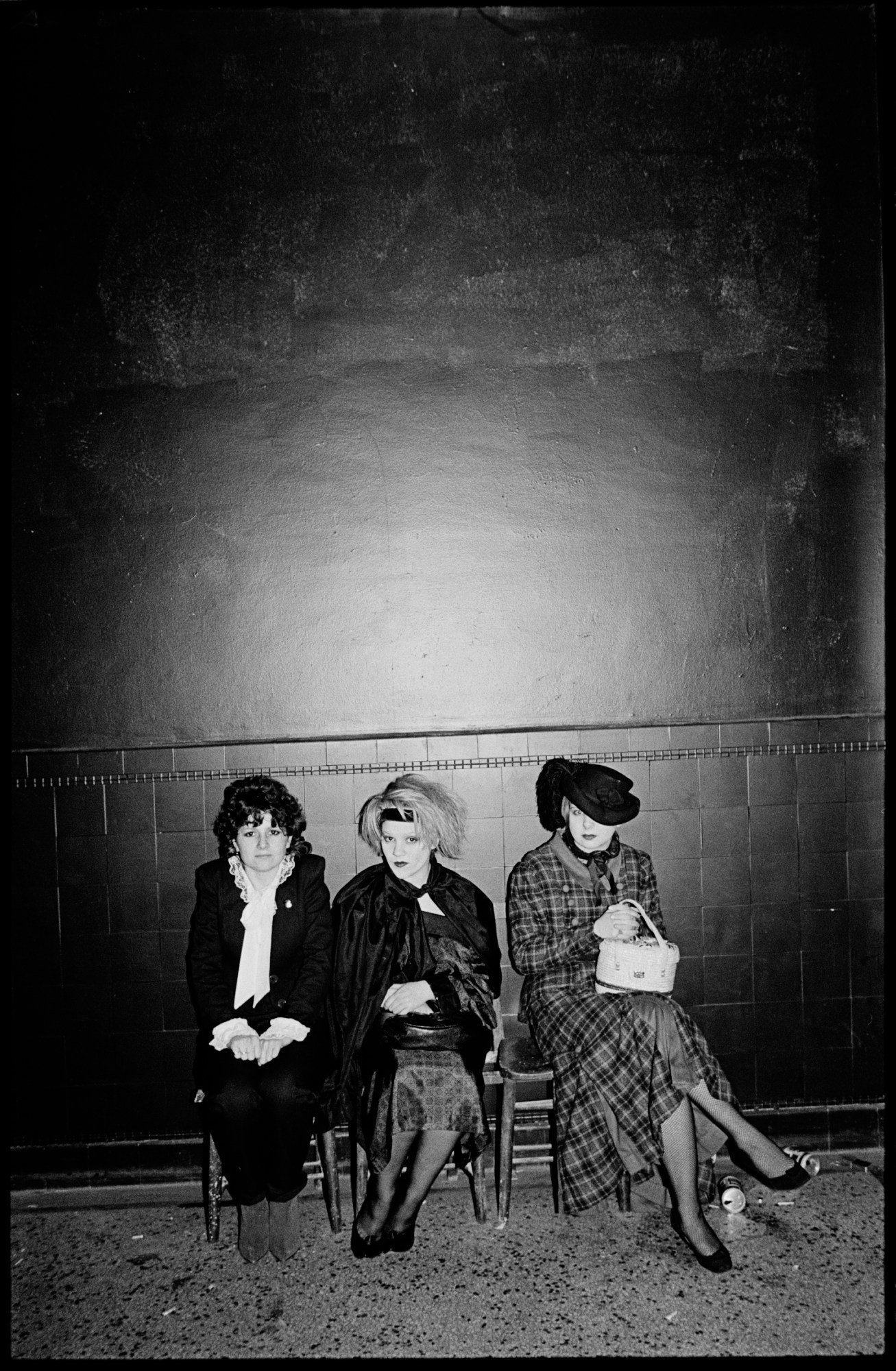

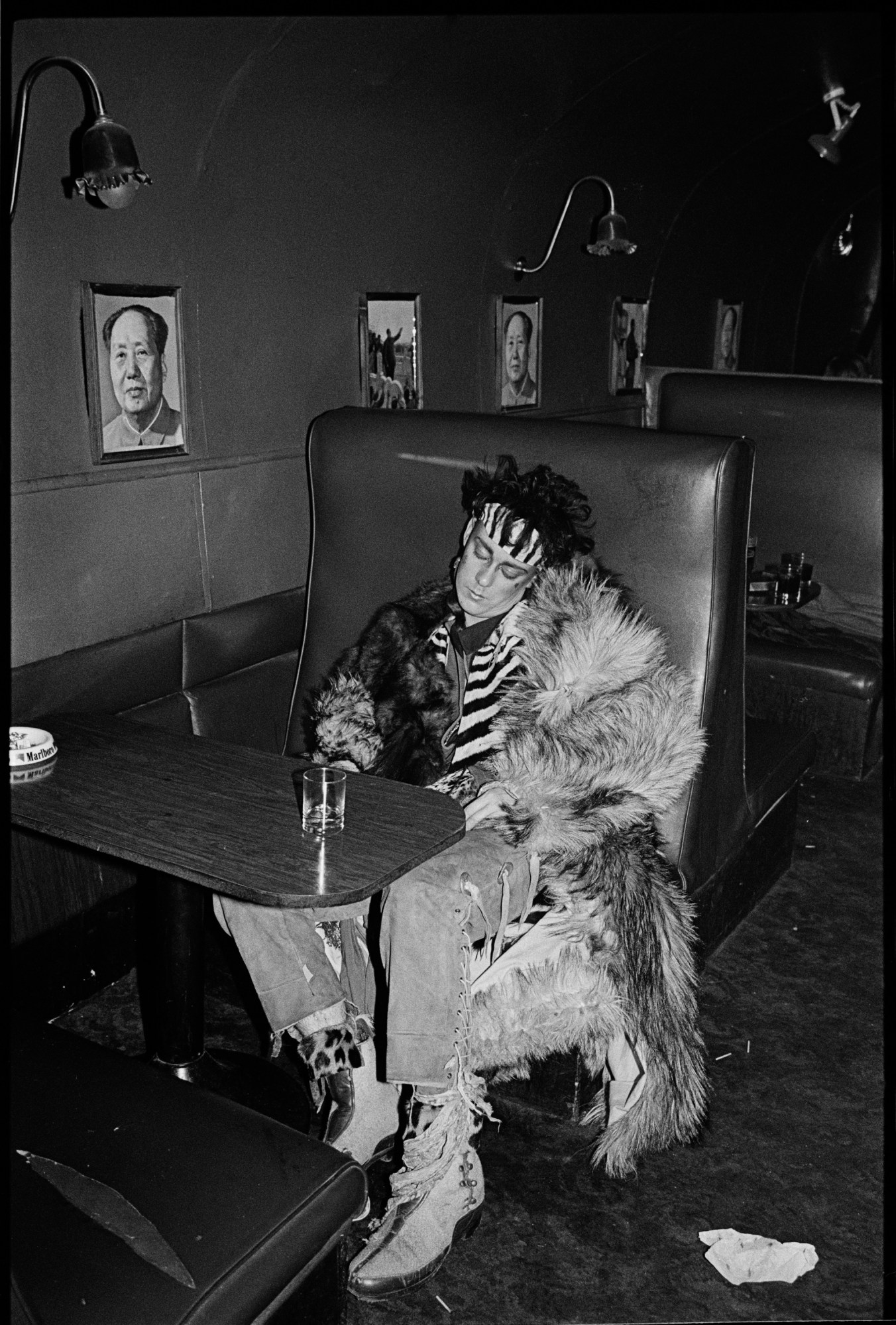

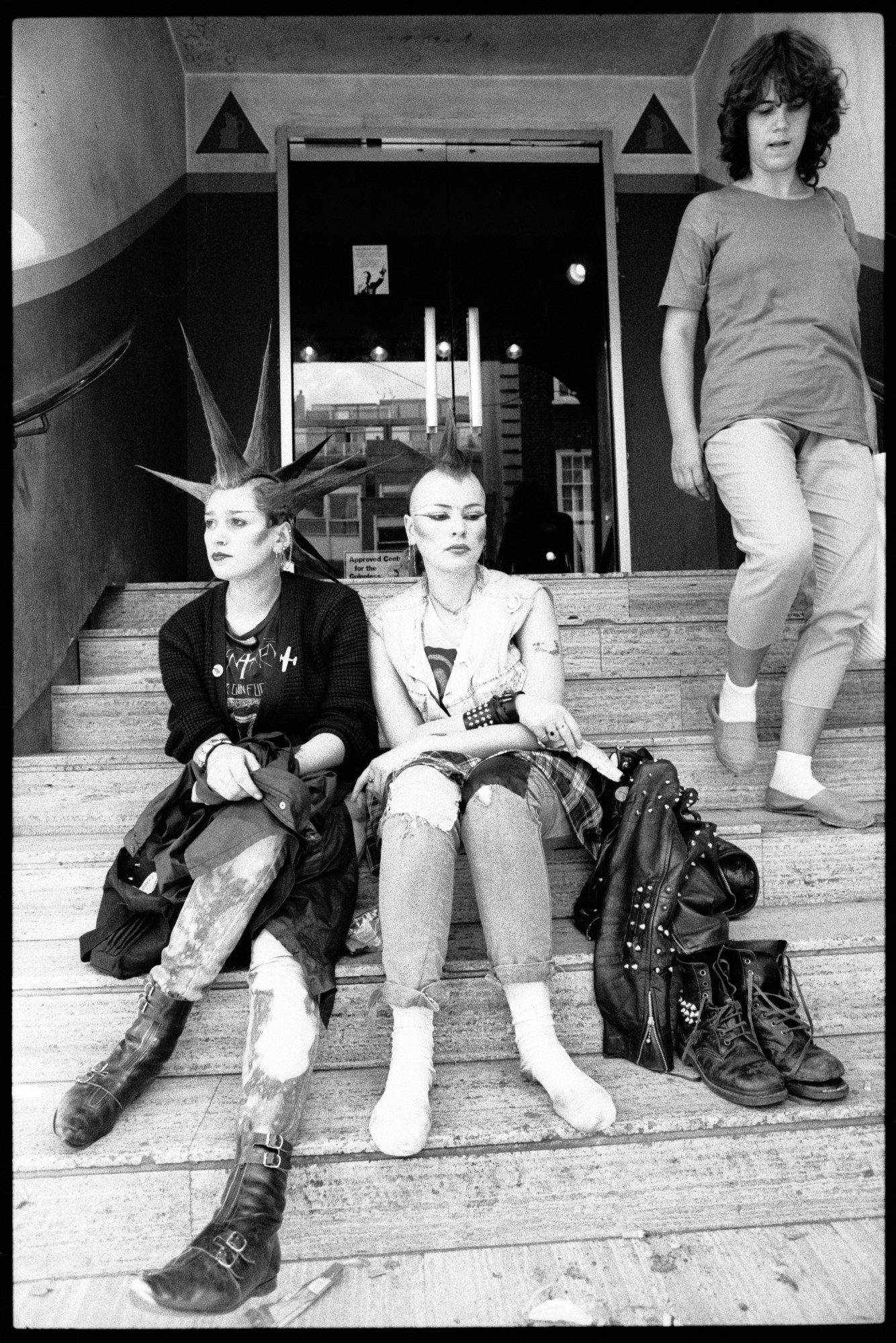

While the Pistols warned of “no future,” a new generation of youth came of age in the British underground, spawning a host of subcultures like punk, rockers, mods, skins and New Romantics during the late 70s and early 80s. As a freelance photographer, Virginia preferred to shoot what she loved rather than take commissions — a decision that gave her complete artistic freedom even if it wasn’t particularly lucrative.

“I would deliver the pictures, and they would use what they wanted; I didn’t have any control and only got paid for what was printed,” she says. “I could spend six days with somebody, and they only used two pictures, or I could do three gigs in a night and have eight pictures published. It wasn’t a regular income, but that was okay because I could do the fun stuff that came from being a fan.”

With the publication of the new trilogy Mods & Rockers Southend August 1979, New Romantics London 1980–81 and Punks 1979–1983 (Café Royal Books), Virginia returns to her archive to pay homage to the fans who build these highly influential DIY cultures from the ground up on the streets of the UK. “You’re not anybody if you haven’t got fans. They’re crucial,” she says. “They go to great efforts, save up money, travel long distances, sleep outside on pavements and floors. They are so devoted. To me, the fans are often more interesting than the band. When people ask, ‘What are you most proud of in your archive?’ It’s definitely the people. It isn’t the artists. And there are some nice touches of Bowie, but it’s not [a picture] having lunch with Frank Zappa. It’s the fans.”

As the underground music scene exploded, Virginia kept pace, shooting artists like the Clash, Blondie, Iggy Pop and Andy Warhol for publications like The Face, Smash Hits, Flexipop and Record Mirror — but she never lost her devotion to documenting the fans. With the passage of time, Virginia’s photographs have become a document of social history, providing a larger context for the intersection of music, style, identity, and youth culture.

Although Virginia’s life has changed since she made these pictures, she remains a fan at heart. “I live in the middle of nowhere, and it’s very quiet. I’m 66 this year and occasionally see these punk bands who are still doing the rounds,” she says. “The gig is full of big, fat blokes in their combat gear, ripped shirts and trousers, and they’re all down in the front moshing. When I’m there, I forget how much I need it. It’s like oxygen to me, being at the front, where it’s sweaty, and everyone’s getting pushed around. I think, ‘Wow, this is it. I needed this.’ This is who I am. This is what feels my soul.”

Signed copies of Mods & Rockers Southend August 1979, New Romantics London 1980–81, and Punks 1979–1983 (Café Royal Books) can be purchased direct from Virginia Turbett (virginia@virginiaturbett.com) for £6.50 plus postage.

Credits

All images © Virginia Turbett