Over the past two decades, we have witnessed a photobook phenomenon, and it’s proving to be no mere fad. With the bibliography of illustrated anthologies on the genre now including over 80 titles, light has, in turn, been shed on the extraordinary history of the Japanese photobook. What struck author Ivan Vartanian while in the midst of writing and editing Aperture’s landmark Japanese Photobooks of the 1960s and 70s (2009) was that photobooks were just one aspect of a much larger culture of print in Japan. “Telling that story meant, in essence, telling the story of Japanese photography history itself,” he explains. “Most of the photobooks that are recognised as masterpieces today began as stories in magazines. They went through an open-ended editorial process via magazine work, which is enmeshed with a whole network of editors, writers, production teams and readers.”

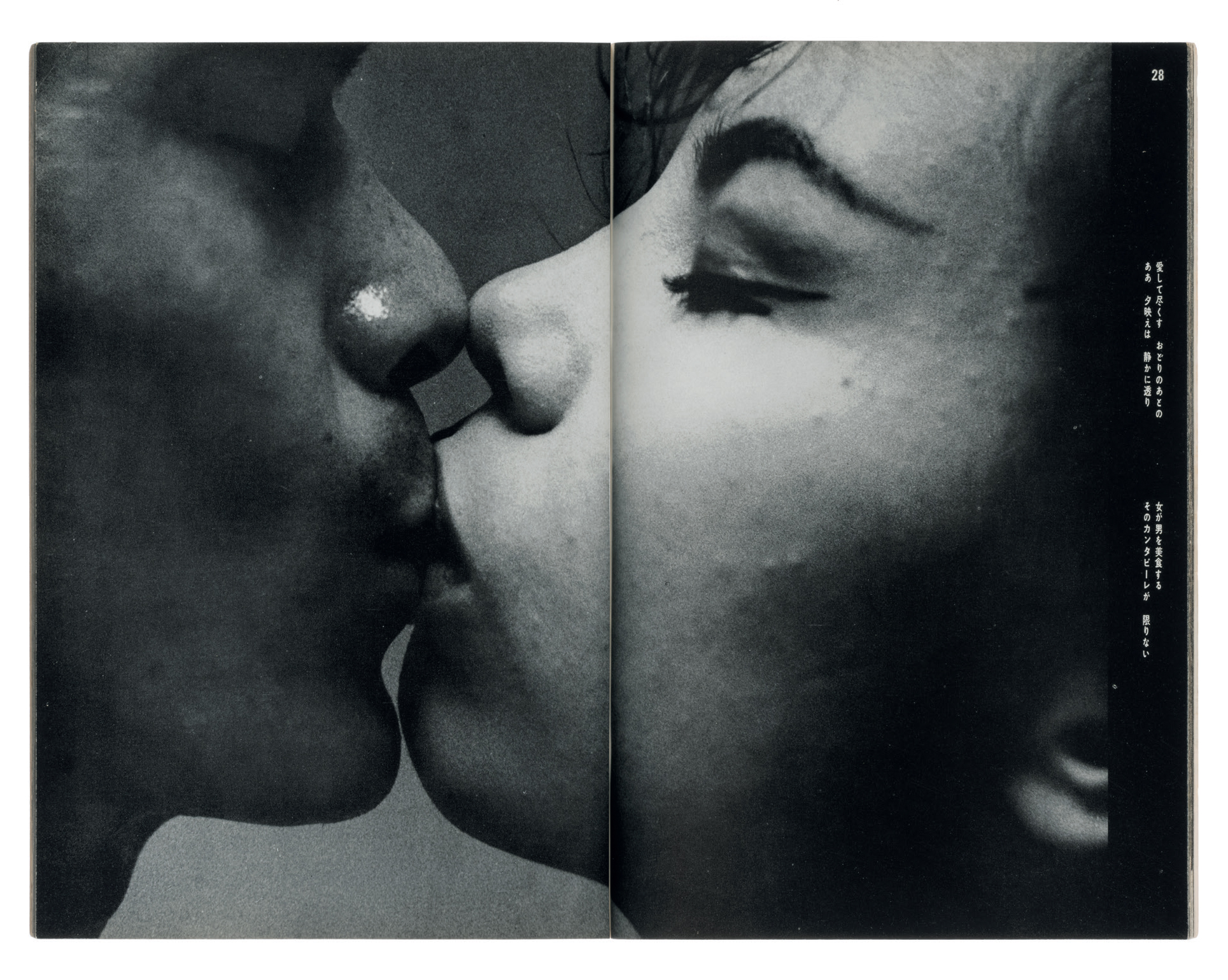

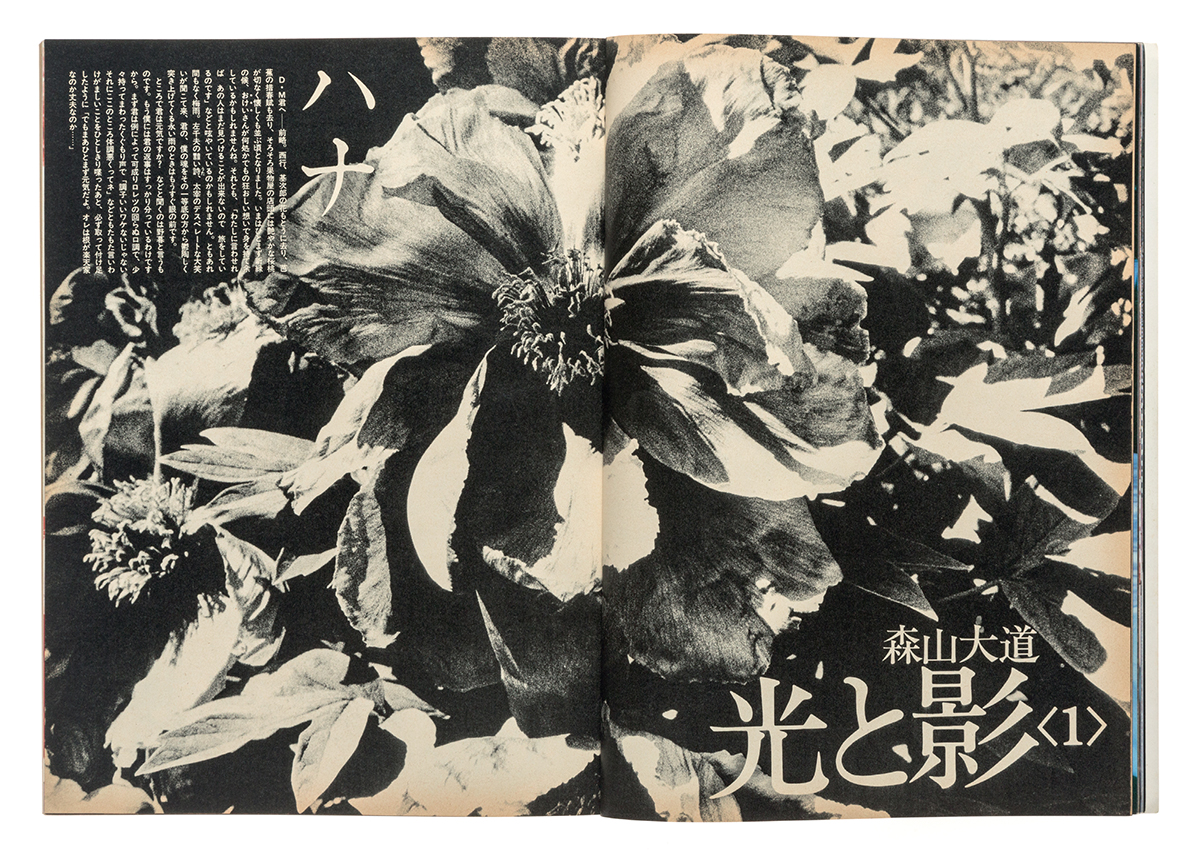

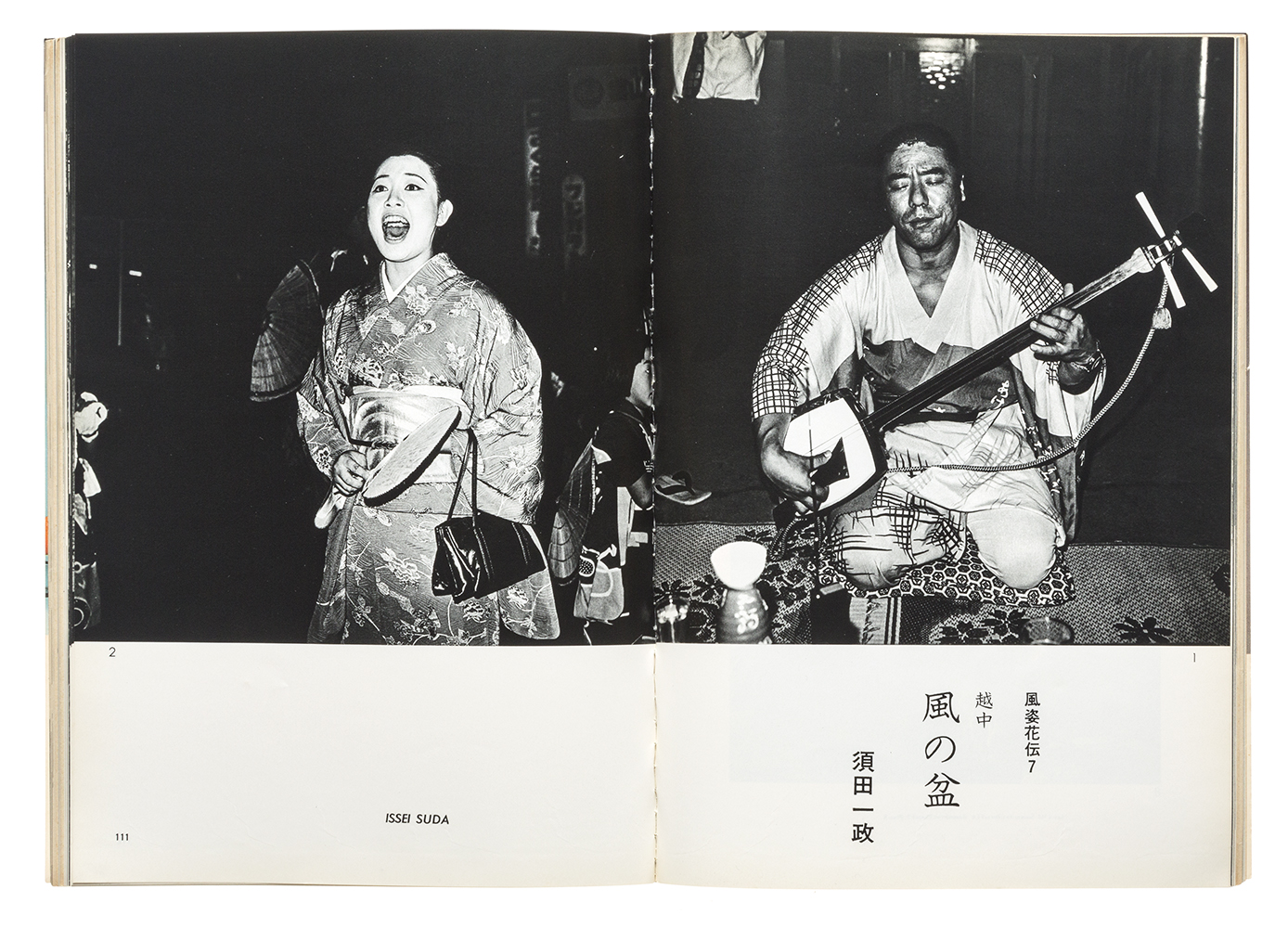

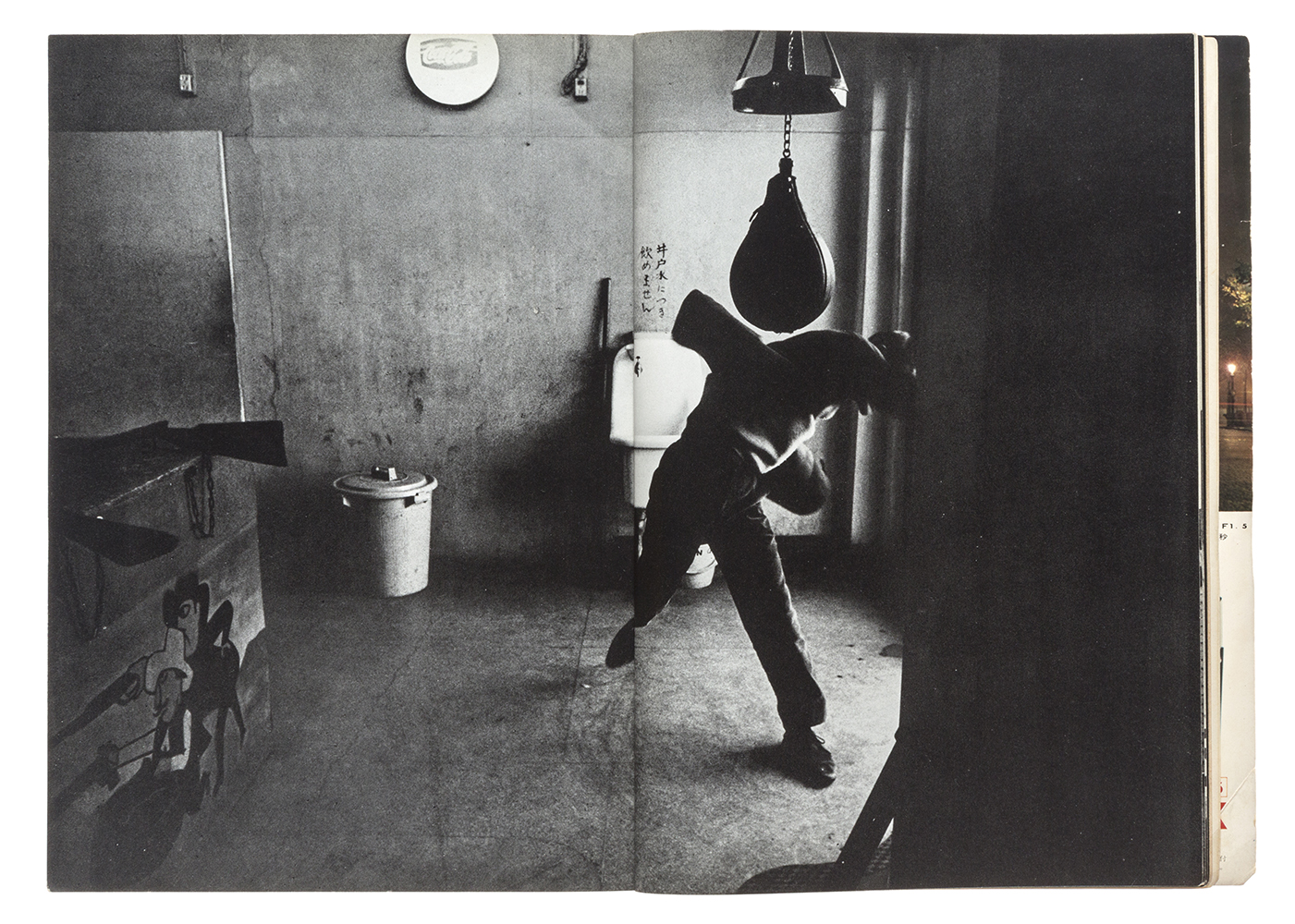

Included in the illustrious list of magazine stories that went on to become masterpiece books are Eikoh Hosoe’s “Man and Woman”, Issei Suda’s “Fushikaden” and Masahisa Fukase’s “Ravens”. Yet there are also many gems which, although never manifesting as books, contributed a great deal to photographic culture in Japan. “There is an enormous wealth of clues embedded in this history,” says Ivan, who, under his own imprint Goliga, has just released a glorious giant of a survey entitled Japanese Photography Magazines: 1880s to 1980s. Spanning a century’s worth of innovative mise-en-page — by your favourites Daido Moriyama and Nobuyoshi Araki as well as forgotten figures too — the book pieces together an otherwise invisible history. It makes the strong case that, from here on in, any discussion of Japanese photography has to include the magazine. Here, Ivan lends insights into its rich and radical history.

Hi Ivan. When did Japanese photography magazines boom in popularity?

It’s interesting because there are no monolithic forms of photography magazines in Japan. There were camera magazines, photography magazines and other types of journals, weeklies and what we would classify today as “zines”. In terms of circulation, camera magazines started to have a relatively wide appeal after WWII, once camera manufacturing in Japan advanced. This needs to be considered in tandem with other industries, including printing, advertising and urban development. Each of these sectors was going through a period of unprecedented growth. The ballooning force propelled the demand for photography and, in turn, the consumption of publications.

Let’s talk about the 60s! Can you set the scene for us?

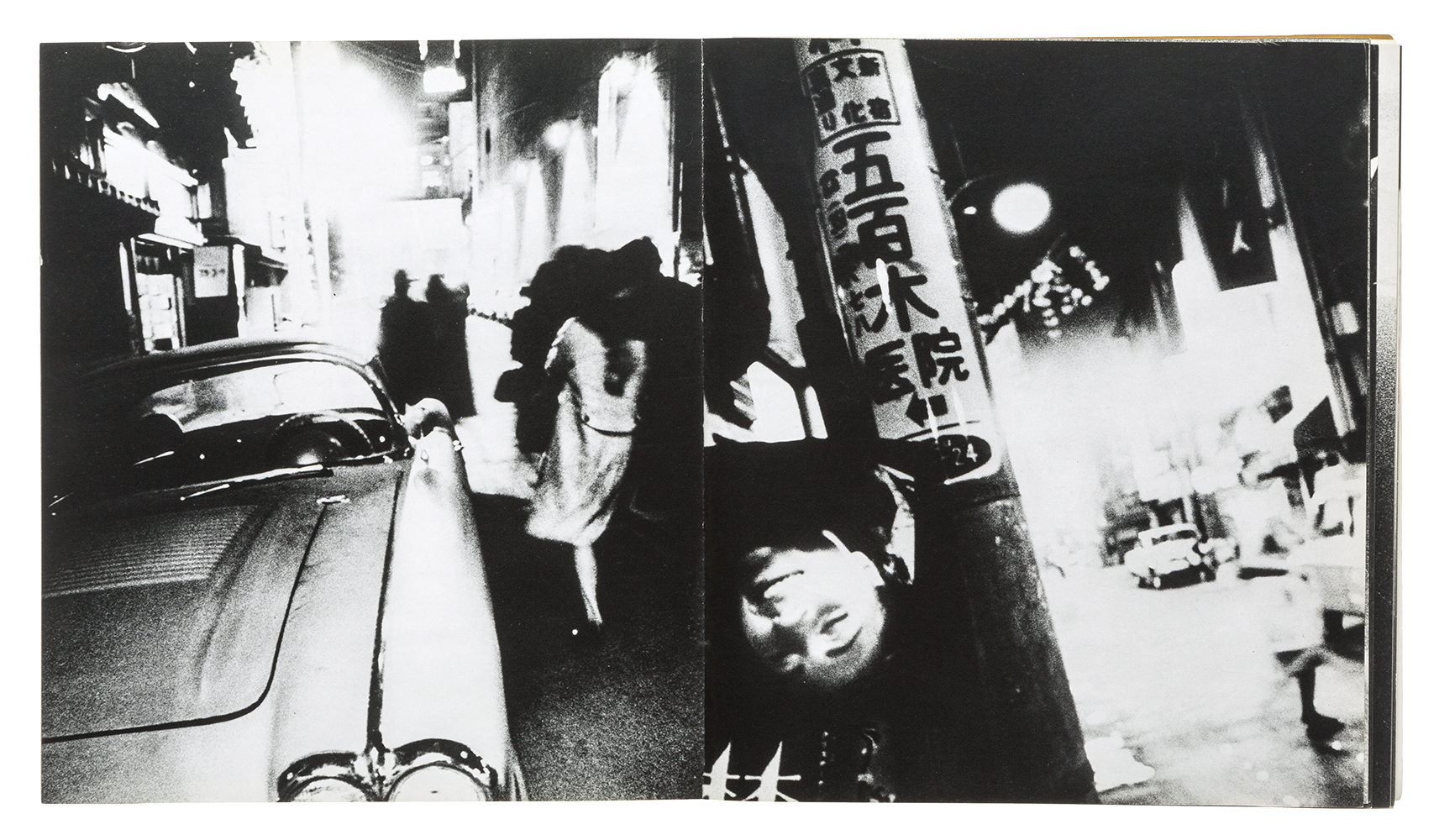

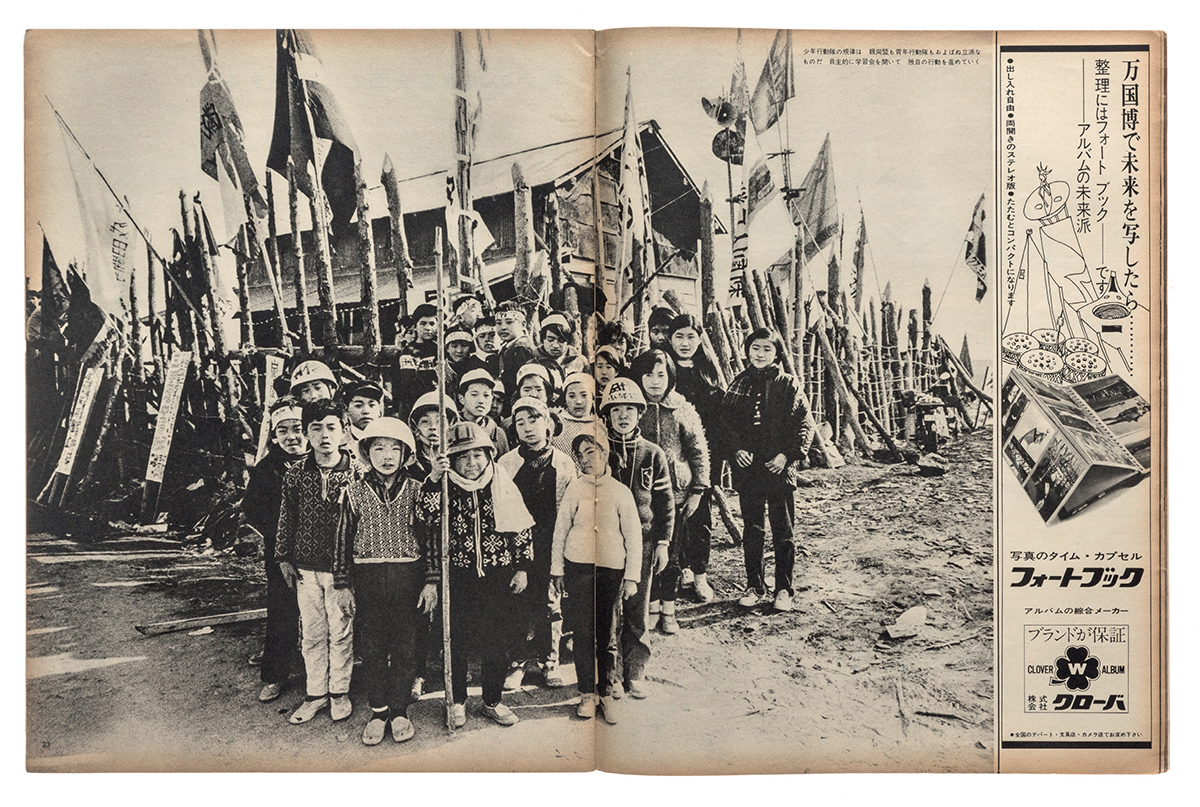

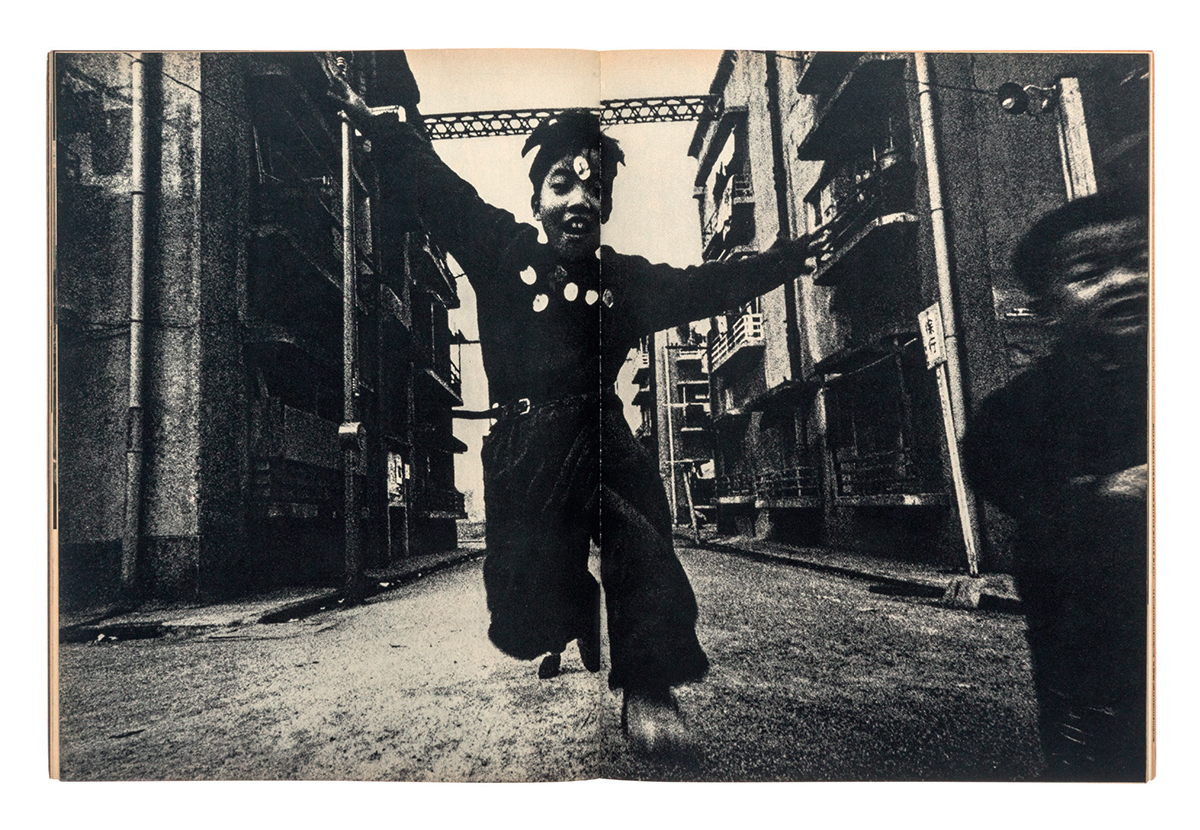

Perhaps change or, better yet, upheaval is a good way to describe the decade. By the time the Tokyo Olympics opened in 1964, the country had miraculously resurrected itself from the ashes of the war. In addition, larger geopolitical forces at play in that recovery would set the scene for an actual and metaphorical battle between the establishment and resistance. The student protest movement, which was a worldwide phenomenon, was also present in Japan, and there was a heightened awareness of social issues that manifested in a lot of photojournalism. All of this flux was the meat and matter for a lot of photography that was produced in this time.

How did this turbulence translate into the magazine pages?

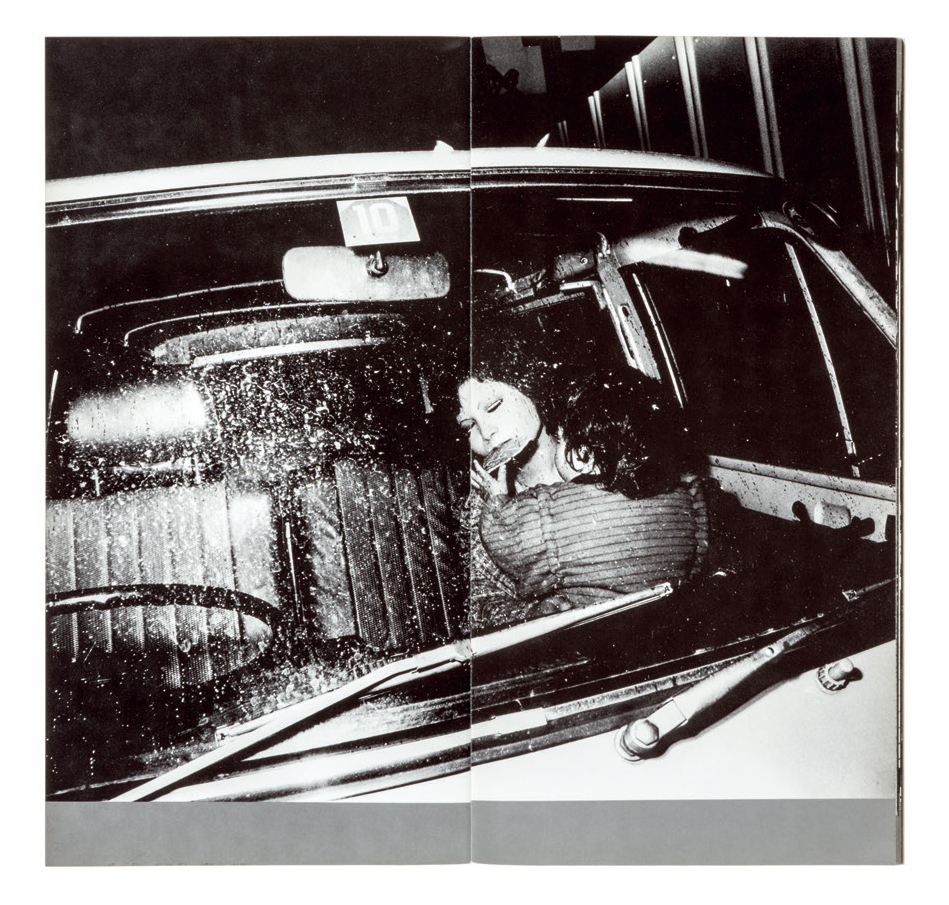

Photography magazines were forums of a sort where photographers, writers, critics and editors could consider Photography (with a capital “P”) and its relationship to society. In this way, they had an urgency to be a necessary mirror of the times. At the same time, the photography industry was going through a “professionalisation”, so, at times, categories of “amateur” and “professional” could result in some interesting twists. For example, a magazine could use a young, freelance photographer who was indistinguishable from those protesting, as opposed to a staff cameraman. In other words, the awareness that the media was a political tool became par for the course. And generating images that plugged into that dialogue was the impetus for many photographers at this time.

Who was the most notable example of someone taking punts on young talent?

Shōji Yamagishi, the editor of the monthly magazine Camera Mainichi. Thanks to him, several breakout stars of the photography world got their first proper exposure. This included Daido Moriyama. Shōji was influenced by the legendary MoMA curator John Szarkowski, with whom he presented a massively important exhibition of contemporary photography to a Western audience. While the magazine culture was riding high, Shōji was at the forefront of what was happening in Japan, acting both as a sponge and as well a bullhorn for new talent.

How did the photo-literature genre emerge?

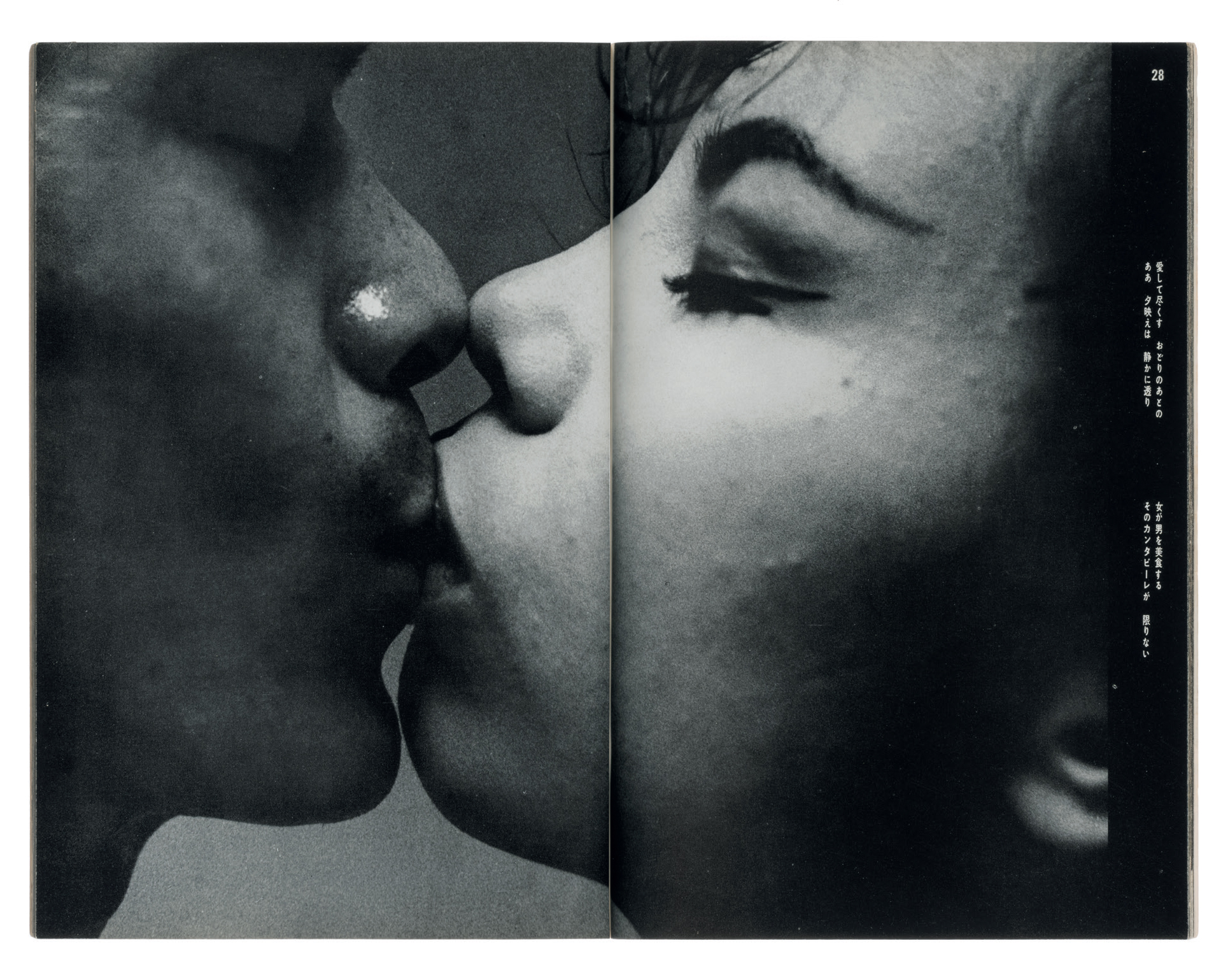

Using text or textual elements to create a composition with photography was something that we started to see in different parts of the world from the 30s. These treatments of photography as components of the printed page made their way to Japan in the form of publications as well as large murals. There is certainly no one tradition of how photography was combined with text. Rather, there have been many approaches that range from dealing with graphic usages of photography or using photography as poetry, as was the case with the poets of the coterie publication Vou. Eikoh Hosoe, in particular, was able to synthesise highly sophisticated layouts that combined photography, poetry and colour, as with his iconic photobook Man and Woman (1961).

I guess we can’t not talk about Provoke…

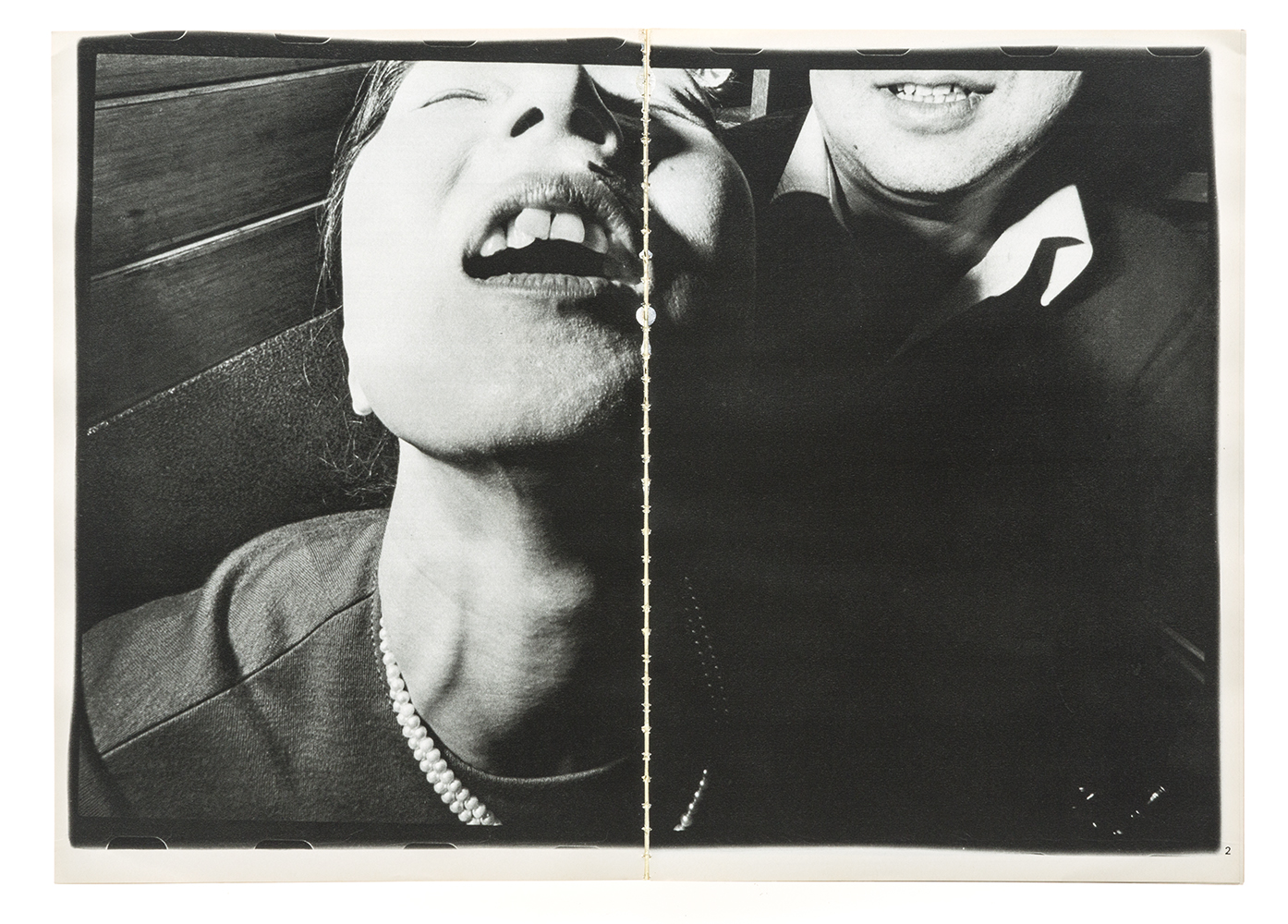

In recent years, the magazine Provoke has received a significant amount of attention in photography circles in the West. There were only three issues of that publication, and it was published by the photographers whose work appeared in its pages. These sorts of DIY publications, known in Japanese as doujinshi, have had a long tradition in Japan. The magazine was devoid of any advertising, and the materials it presented were meant to provoke the reader. That can be read as agitation, disruption or stimulation. These photographers were making work at a time when conventions of “nice photography” were castrating the radical potential of photography and its ability to upend things. That’s the core ethos of that project, and the photography did take up specific issues, such as urban sprawl and homogenisation of the country. But Provoke was less about specific issues and more about a stance of resistance to make something new.

How significant were serials — “rensai” in Japanese — in the elevation of a photographer’s reputation?

Periodicals dedicated to cameras and photography were populated by serials that generally ran for a year. Usually, a photographer was given a few dedicated pages to appear in each consecutive issue of the publication. And this was all new work for the most part. So, over the course of the serial, a photographer had access to a broad audience with immediacy. And since there was an active discourse in print, photographers could get what was essentially feedback. Serials that resonated with an audience got renewed for subsequent runs. Particularly popular serials, such as Issei Suda’s Fushikaden or Kazuo Kitai’s To the Villages, built up enough of an audience that a photobook seemed like a commercially viable and natural next step.

The photobook has often been perceived as the ultimate manifestation of a body of work. That’s a pretty romantic notion, which your survey looks to dispel.

The photobook is just one part of the conversation. One of the reasons why photobooks have become so popular is because their appreciation dovetails with previously established ways of seeing photography as the work of an individual in isolation, creating “something from nothing”. This is an extension of the contemporary trend to recategorise photographers as artists. There is, of course, a time lag between a photobook’s publication and when the work was originally shot, and, oftentimes, photography can get stripped of its native context in a process that mythologises the photography, particularly when it comes from the easily exoticised far east.

Looking at photography in magazines not only puts work in context but it also shows all the myriad connections that were essential for the generation in the first place. So often, photography is a response to – or an attack – on some other body of work. Looking at the photography in situ allows a glimpse at the dynamism and real-time discourses that fuelled some of the most spectacular and genre-bending photography we have ever seen.

‘Japanese Photography Magazines: 1880s to 1980s’, authored by Kaneko Ryūichi, Toda Masako and Ivan Vartanian, is published by Goliga.

Credits

All images courtesy of Goliga