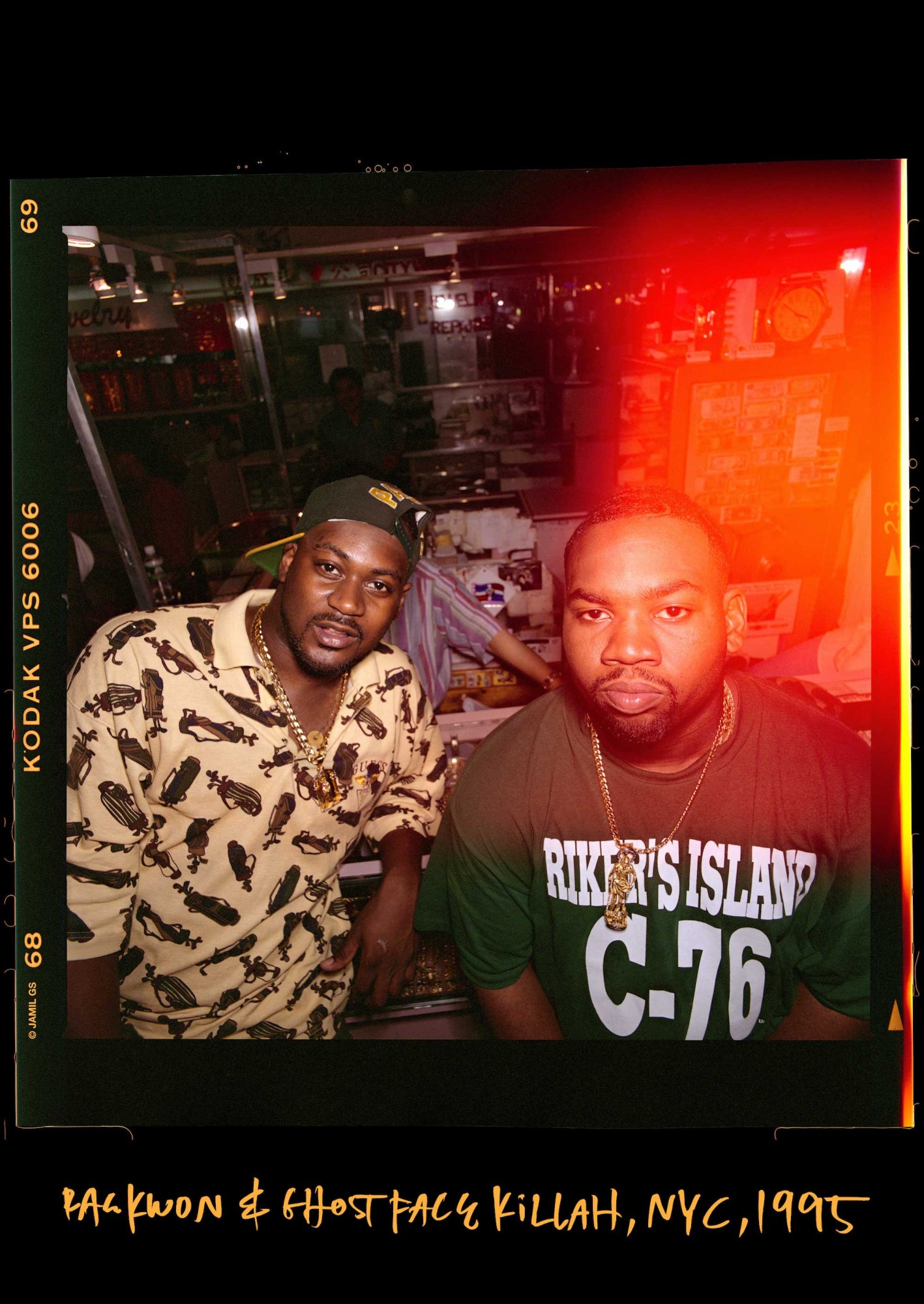

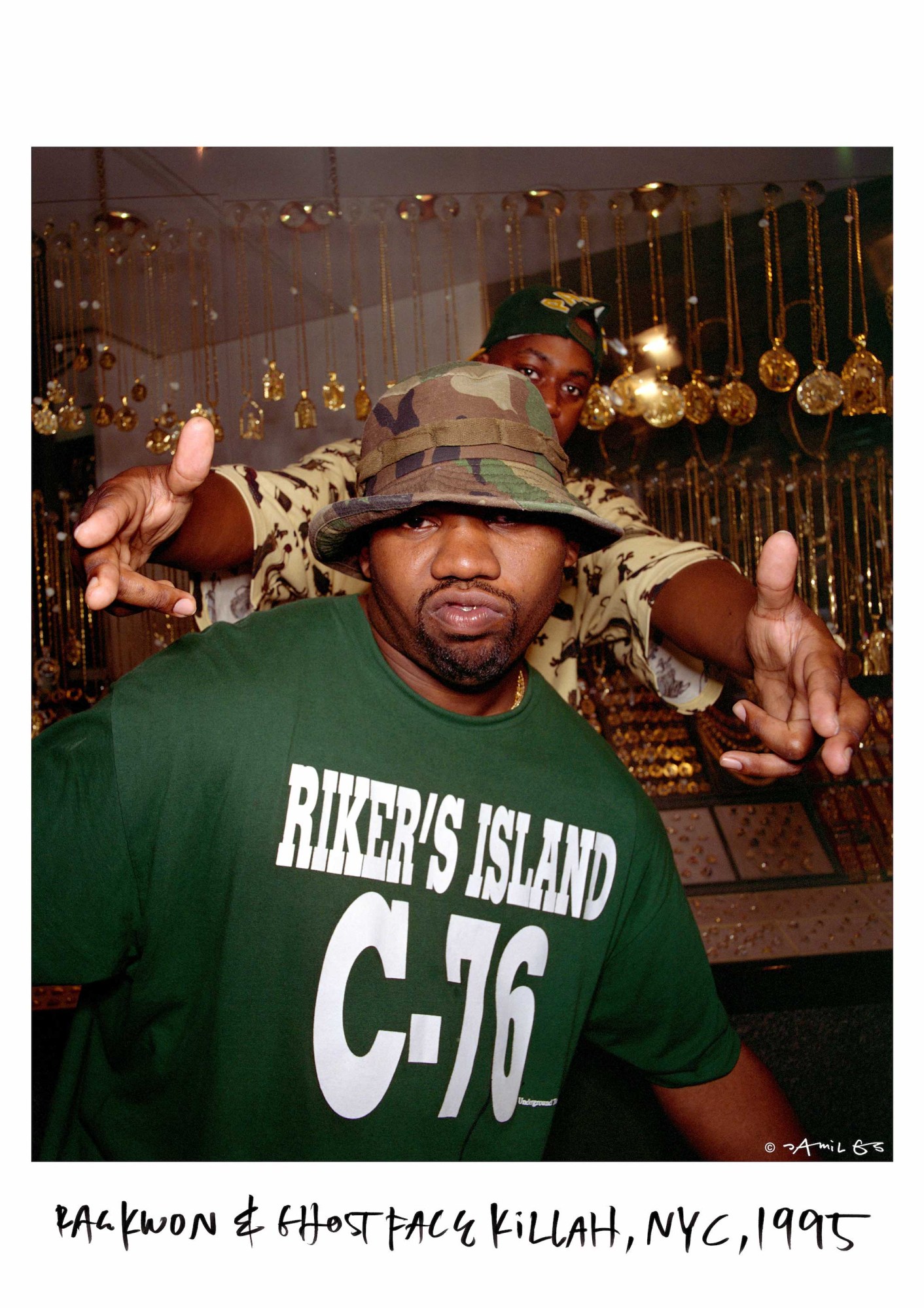

Since its early days in the 70s, being seen in hip-hop has been nearly as important as being heard. And once the genre began to dominate the mainstream, with artists like Wu-Tang Clan and JAY-Z becoming pop cultural forces, it was even more important that fans could see the actual people behind hit songs and huge fashion trends. That’s where some of hip-hop’s legendary photographers like Jamil GS come in.

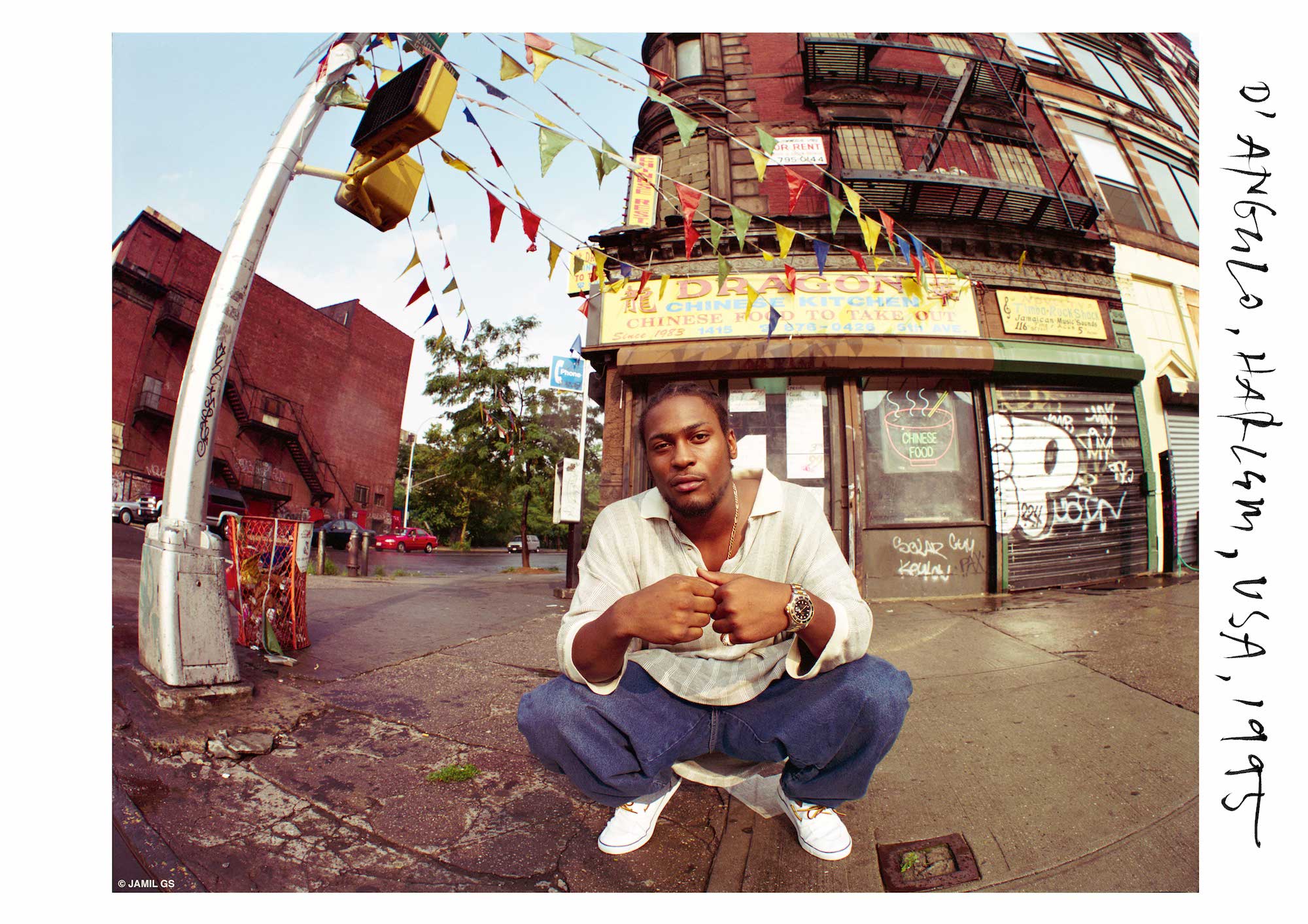

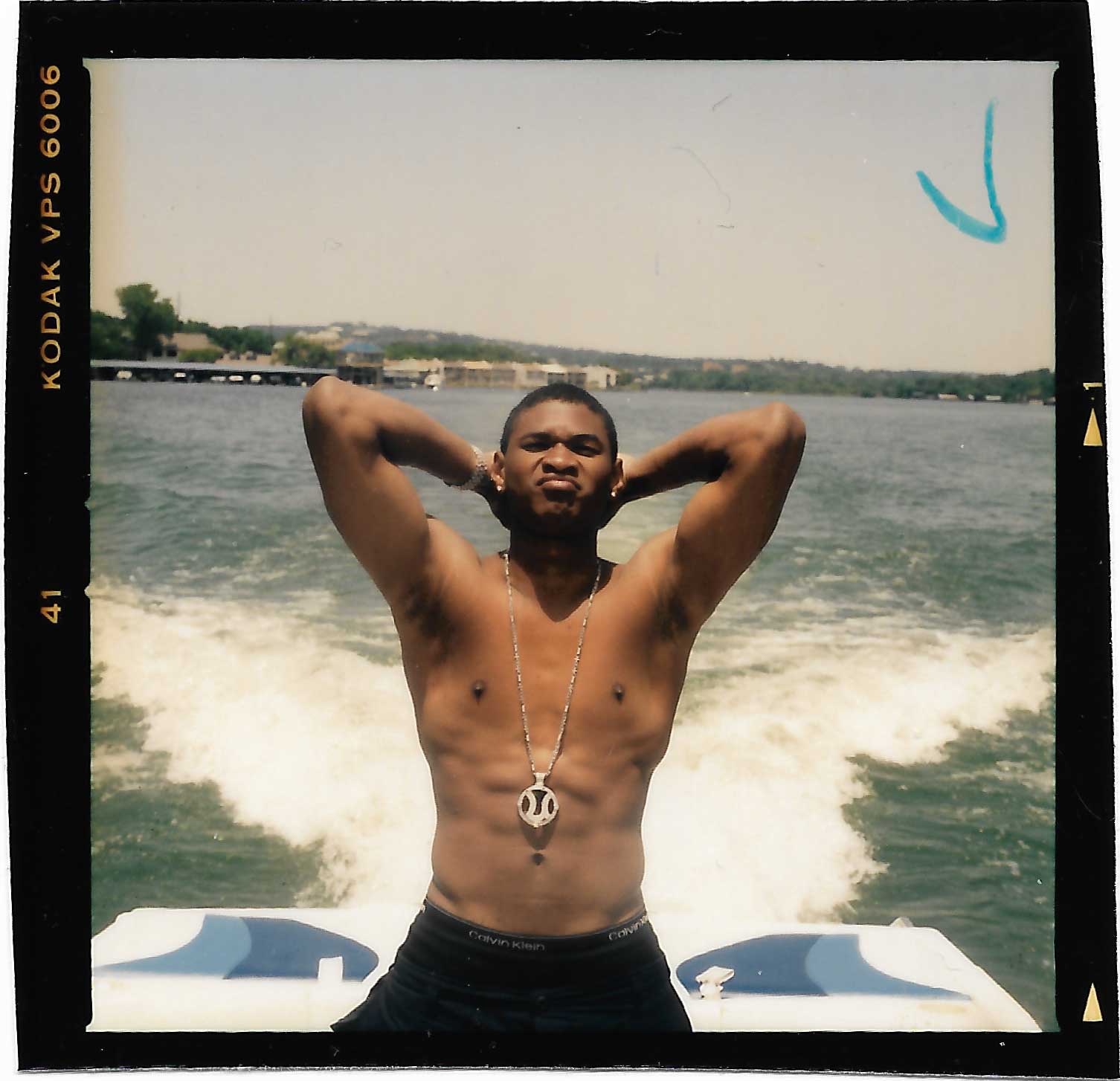

Born in Copenhagen to Muslim jazz legend Sahib Shihab and Danish native Maiken Gulmann, Jamil had a multicultural childhood and immersed himself in hip-hop as a graffiti artist and b-boy. Following his father’s death, he moved to New York and began taking photographs, his first major placement being a street fashion shoot of Boricua women in the Bronx for i-D in 1994. He became renowned for his music portraiture, working with D’Angelo, Juvenile and Queen Latifah, while also shooting extensively in Jamaica.

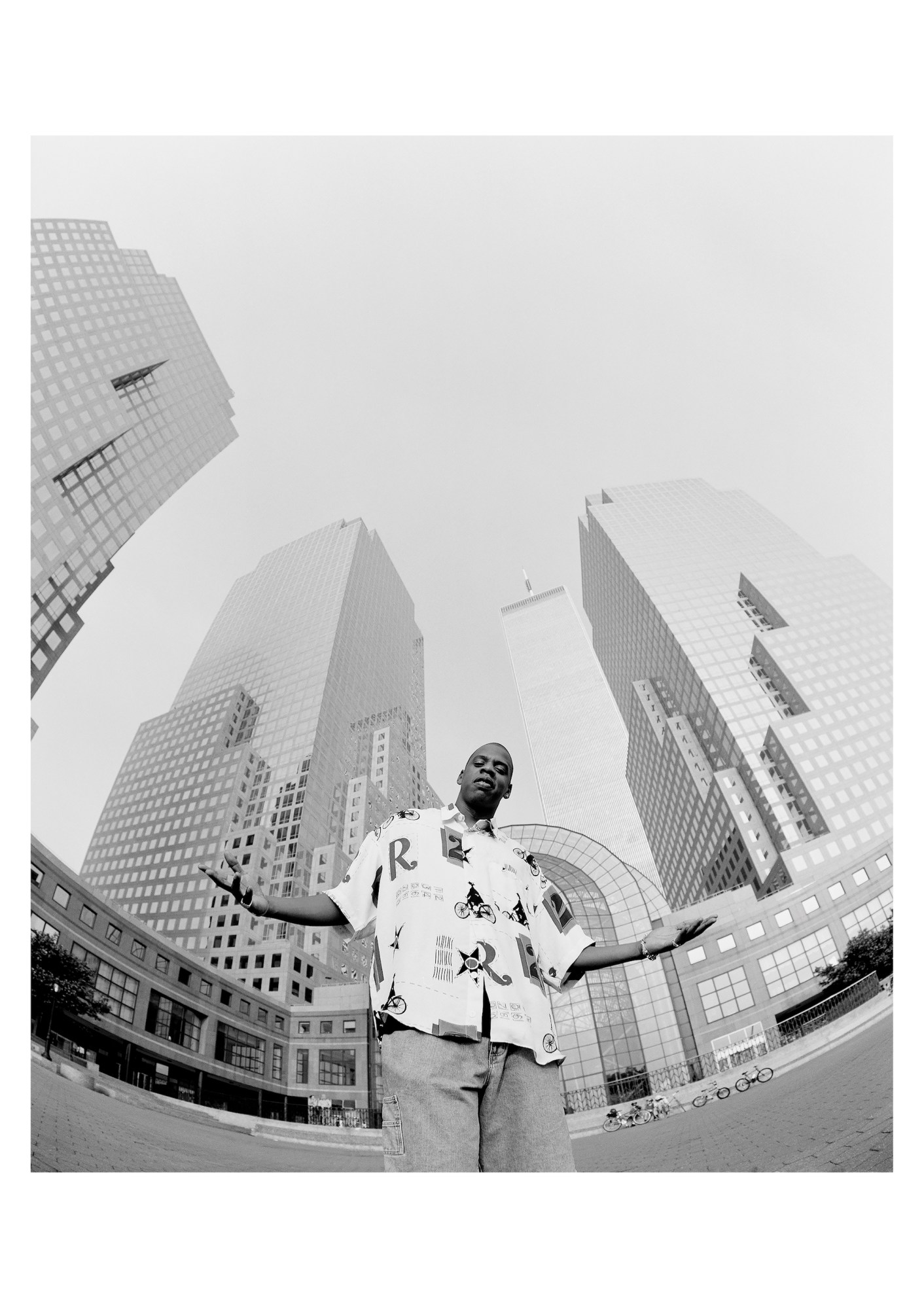

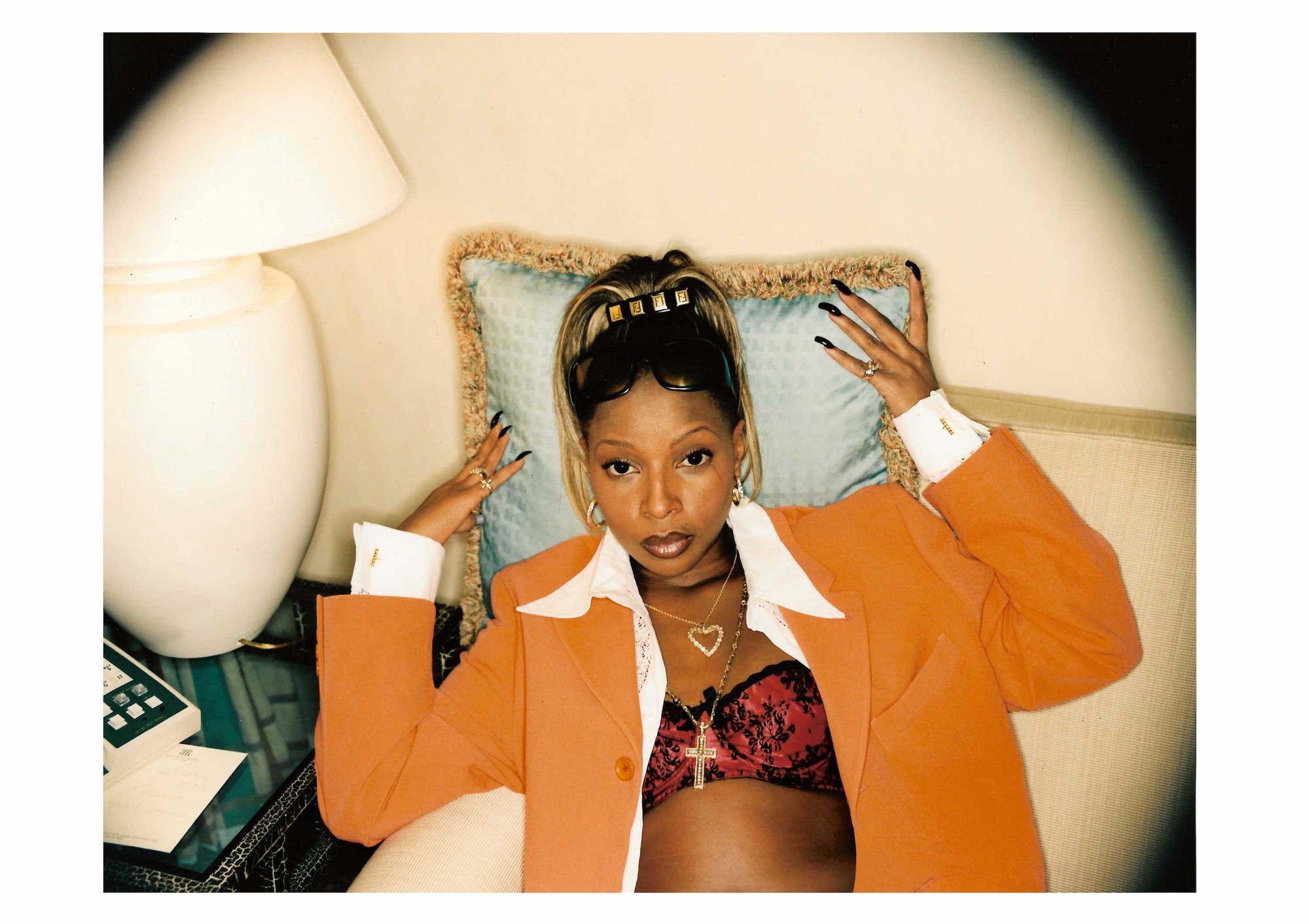

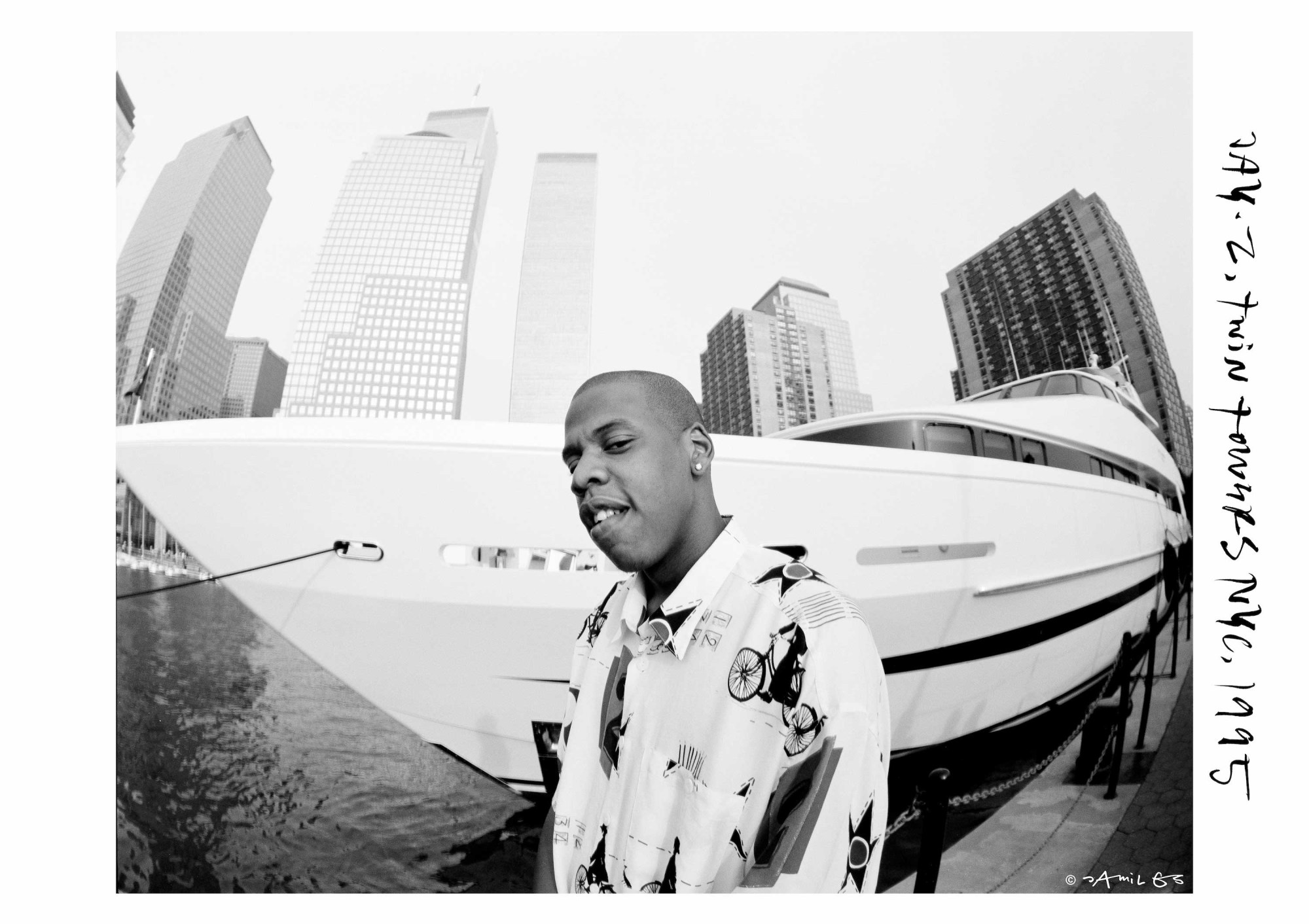

A hallmark of Jamil’s photography is a sense of both elegance and grit, embodying not just the hardscrabble origins of many musicians, but also the stratospheric heights they would go on to reach as rap became a global lingua franca. It’s evident in this striking, sanguine portrait of Mary J. Blige from 1997, a young Faith Evans who he shot for i-D, and, of course, the larger than life image of JAY-Z standing at the World Trade Center that is available for purchase in his newly launched web store, The Dope Hip-Hop Shop.

“The shoots that I did back then, most of them were very low budget productions,” Jamil says. “[My aim was] to really lift everything and make space for hip-hop, but also for Black people in general and people of color. They weren’t valued back then, either, specifically not in mainstream media.”

With The Dope Hip-Hop Shop, Jamil sells versions of some of his most striking images as posters and tees at a more accessible price point, while also showcasing his work through the years — the first drop of photos being from 1995. As rap music has grown more popular and social media gives artists a place to share images and videos, documentation has become a constant in the genre. But the groundwork for hip-hop’s aesthetic dominance was in part laid decades ago through the work that Jamil and his peers did for outlets like The Source, XXL, The FADER and Rolling Stone. These young, diverse photographers helped recontextualize hip-hop from something often misunderstood and maligned into a unique celebration of Black culture, first in the US and later around the world.

We spoke to Jamil about opening his new store, how the relationship between rap and photography has evolved and the legendary late photographer Chi Modu.

Given how many artists you’ve worked with, how did you go about choosing which images you wanted to be part of The Dope Hip-Hop Shop?

I’ve been doing exhibitions since [I was young] and then selling prints directly to buyers and collectors and stuff, but this was a time for me to get organized and do it in a different way. Because the prints are fine art, they have a fine art price tag, so I’m trying to create a situation that’s a bit more accessible for more people.

And as far as choosing what to present, honestly, I’m still figuring it out. [I thought] let me start off by doing something chronological. That ended up being JAY-Z from 1995, because that was one of the premiere record industry shoots that I did. This is when I started. This is my foundation, and it’s also the beginning of an era. It’s an evolution from early hip-hop to the era of hip-hop. It’s an important time for hip-hop but also an important time for photography.

How do you think the relationship between hip-hop and photography has grown since your early days?

Photography wasn’t valued back then. It was just a necessity. No one knew the importance of the documentation of that time, of the artists at that stage. I was a tremendous hip-hop head and I had it in my headphones 24/7, but I don’t necessarily think these artists were checking for photography and art the same way. They’ve come around.

A lot of your work is about capturing someone in their environment. Going up to the Bronx and shooting Showbiz & A.G. or Juvenile around the Magnolia Projects. Now there’s so much more photography, but also, there’s less context around music, in part because everything comes out on the Internet. Is it a challenge now for photographers to capture a musician in their context and make images feel unique?

Yes, but hopefully something new is bubbling. When it comes to hip-hop it’s difficult because hip-hop now has such a deep history. When I started shooting these young artists, hip-hop was still very young and it was the underdog. It hadn’t really proven its place yet. A lot of people, even record companies, didn’t necessarily believe in its sustainability. It hadn’t really reached the multiple platinum [plaques]. It wasn’t a multi-billion dollar industry yet. It was still fresh. [Artists] didn’t have decades of history to lean on or as a departure point to look at or reflect on and say, “Okay, what am I trying to do from this vantage point?” There were opportunities, for sure, but not as many. We didn’t have a JAY-Z back then. We didn’t have rappers who were billionaire businesspeople. So now, every other rapper is looking at that as a potential opportunity and why not, right? It’s like, “Maybe I’m not the greatest rapper, but I could be the greatest businessperson.”

There has been a bit of a swell in the last few years of appreciation for the work that you and other photographers like Chi Modu did early in your careers. Do you think that’s happening now for any particular reason or do you think it’s just fortuitous timing?

No, I think it has to do with the fact that you were born into a very specific era. It was specific in New York and in LA, and later on in the South. The 90s in New York, it was sort of like the 60s for my parents’ generation. It was wild and free, pre-Giuliani. Looking back at it, it was pretty crazy.

A lot of the work that was created at that time encapsulated that energy. Then you’re listening to the music from that time, as well, and you can feel it in the music, too. For me, every time I see the images or I listen to the music, it’s a time capsule. It’s a frozen moment that you can just reopen. For someone like you, who’s born into that era, it’s also part of you. Even though you were a kid, you still were there. You were alive. You absorbed that vision, too, through the ether, you get me? So you’re gonna resonate with that as well. Anyone who was in that physical space, like New York, LA or Miami, they’re gonna feel it. Over here in Europe, you have people who are so far removed from it, but they feel it, and they feel it mostly from the echo of everybody else.

You had American ties, and spent plenty of time around the US, but was it easy for you to gain acceptance and access in the world of 90s hip-hop coming from Copenhagen?

It was the same as if someone was coming from Brooklyn going into Queens, you know? If someone comes from downtown going uptown, you’re in someone else’s turf. I lived downtown, and most of the artists came from Brooklyn. We’re in a neutral space. I was a young cat in my early 20s, but [I was] a straight up b-boy. The rest of these artists, we’re pretty much the same age. Some of them, I would recognize from the clubs and stuff. We’re in the same environment, just one youngster to another youngster doing their thing.

I think the fact that it was very clear and understood that I was there to elevate the culture [made it easier]. That was my mission. I saw the beauty in these people and I did whatever I could to enhance that and dignify them. There was nothing lost in translation.

I was reading something you wrote when you did the American Royalty exhibit, about the idea of “Ghetto Fabulous” photography, where you wanted “to help take hip hop [sic] from the streets to the yachts and penthouses.” Is that still something you think of when you’re going to shoot an artist today?

Not really. I’m trying to look more at the human aspect. Depending on who the artist is, honestly, they all have their style and what their environment might be, but I really am focused on the human being. “Ghetto Fabulous” ties back to the element of dignity; that’s something that I always want to pull out and really focus on or enhance. It’s like, “This is a photo session, not strictly just a candid moment. We can make the environment look candid, but you as a person, this picture is gonna last 100 years. How do you want to represent yourself?”

At this stage of your career where you can afford to be pretty selective about your projects, what makes a new artist interesting enough for you to want to work with them?

I’m really interested in the music. Music can be spiritual and it can be very important, so if someone has an element of that — or if I feel they have the potential of that [I’m interested]. I love when I hear something and I’m just like, “This is dope.”

I know that you and Chi were really close and came up as contemporaries, so I wanted to give you some space to talk about him if you’d like to in the wake of his passing.

One of his monikers was “The People’s Champ,” and he really was. I’ve been selling prints and artwork throughout time, but as far as setting up The Dope Hip-Hop Shop, he was instrumental in that. He’s got a few years on me, so he’s been organized in that field for a while. He’s really motivational, so I owe a lot to him for that.

He’s been sticking his neck out for all photographers as far as copyrights go. That’s why he’s the people’s champ. He’s done some really important work besides his photography, which is iconic, and has a legacy that is going to live forever.

Be sure to check out Jamil GS’ rare prints, posters and T-shirts at The Dope Hip-Hop Shop here.