After gaining independence from France in the summer of 1960, Senegalese film production became the epicentre of a postcolonial coming-of-age story, and has since been heralded as the capital of African cinema on a world stage. Often, these films celebrate the in-betweens of place and national identity, capturing the historical representation of the people and communities surviving colonial rule.

The films made by Senegalese artists are inherently transformative — not just for their political undertones but for their genre-bending nature. Instead of centring trauma, the movies Senegalese filmmakers make tend to skirt the white gaze of the oppressor entirely. They also reconfigure traditional film production techniques. Often referred to as the father of African cinema, director Ousmane Sembéne utilises low budgets, amateur-yet-comfortable acting and little to no camera movement or close-ups. Another icon, Djibril Diop Mambéty, blends a discontinuous, disruptive and often satirical style to create a nearly constant state of alienation for the viewer.

Some may call these stylistic sensibilities ‘avant-garde,’ making Senegalese films seem intimidating. But while their content may be heavy at times, their intrinsic creativity makes for an exciting and fruitful watch.

The entry point is… La Noire De (Black Girl) (1966)

Ousmane Sembéne’s feature-length debut set the critical tone for Senegalese cinema for the next two decades. The story follows Diouana, a young Senegalese girl who moves to France to work as an au pair for an upper-class white family. When she arrives, Diouana is quickly mistreated and incarcerated in their apartment. Language and speech play a major role in most of Ousmane’s films to show power in its most diluted form. In La Noire De, Diouana does not speak at all, except for a stream-of-consciousness voiceover to portray her sense of isolation, subliminally critiquing the lingering colonialist mindset of the supposedly postcolonial world around her. The French-language title, La Noire De, translates to both “The Black Girl of” and “from”, signalling a double meaning of ownership and belonging — the two major themes of this masterpiece.

The one everyone’s seen is… Atlantique (2019)

Mati Diop’s mythological romantic drama unfolds like an eerie dream. 17-year-old Ada falls in love with Souleiman, a construction worker, after being promised to another man. The film starts like a love story, switches to a crime thriller and eventually lands on paranormal phantasmagoria. If you’re a fan of twists and turns, Atlantique will have your stomach in a ferocious knot as it retells the migrant story from the point of view of those left behind.

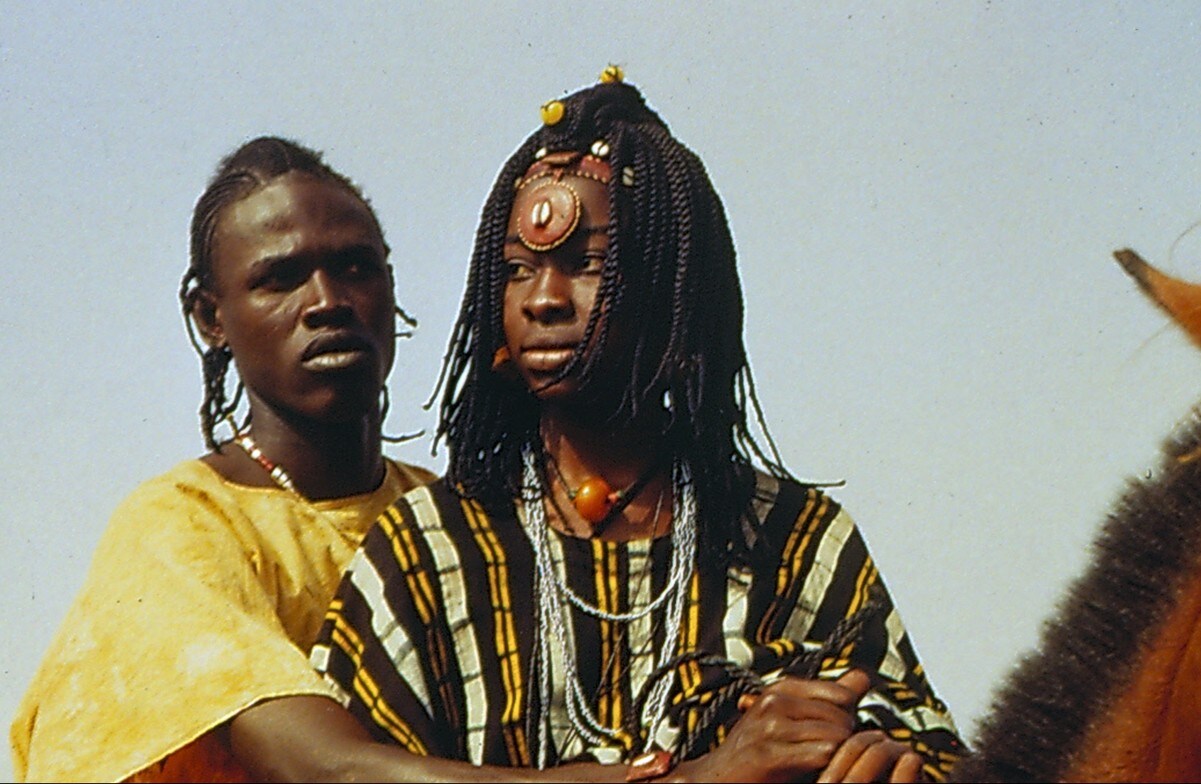

Necessary viewing… Touki Bouki (The Journey of the Hyena) (1973)

Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Senegalese classic is more generally known for its celebrity status – Martin Scorsese called the film “a cinematic poem with a raw, wild energy”, while Beyoncé and Jay Z appropriated the film’s imagery for their On The Run II tour video. Touki Bouki chronicles a couple’s attempts to escape their village surroundings for a taste of Paris, which they see as ‘paradise’. The duo, Mory and Anta, embark on a series of petty crimes, Bonnie and Clyde style, until Mory hits the jackpot. Most interestingly, Djibril contrasts the recurring postcolonial dream (or nightmare) of migrating elsewhere — usually to a coloniser’s land — with an audacious soundtrack. For instance, by splicing Josephine Baker’s “Paris Paris” with indigenous music played on a Peul flute (a common instrument for the nomadic Fula people). It conveys the disillusioned utopian desire for freedom while removing Josephine Baker from her Eurocentric habitat and repositioning her within an African context, asking the question: “What is home?”

The under-appreciated gem is… Mossane (1996)

Anthropologist-ethnologist-director Safi Faye is criminally underrated, even though she has created some of the most influential African films of the 80s and 90s. Safi is known to foreground female experiences within the rural sectors of Senegal. In this film, titular character Mosanne is a 14-year-old girl who has just reached marriageable age and is adored by many in her rural village, particularly for her beauty. Even her brother Ngor is in love with her. However, Mosanne is in love with Fara, a poor student. The issue is that, at birth, she was promised to Diogoye, an emigrant earning a living in Paris. Mosanne’s tragic love story plays havoc with traditional familial dynamics and pushes boundaries for what it means to rebel against ‘destiny’ or ‘fate’, and what it means to be a woman.

The deep cut is… Ceddo (1977)

Ceddo was released in 1977 and promptly banned in Senegal, allegedly for the misspelling of its title, but most probably for its criticism of Senegal’s dominant religion, Islam. Set in a 19th-century village, it follows the life of a kidnapped princess while a Muslim imam struggles against a Catholic priest for ultimate religious and political control. The Ceddo, an indigenous group, try to hold onto their traditional ways. Ousmane Sembéne attempts to rewrite an African history on African terms with this film, while experimenting with an entirely new tonal sensibility. Unlike La Noire De, Ceddo he replaces his venomous anger with a dark sense of humour.