Glimmering neon lights cast an uncanny sheen across a sex shop’s billboards that boldly state, “I like to watch” against blown-out posters of women in lingerie. Men who walk by cast their eyes upwards towards these towering seductive figures, unable to control themselves. Bette Gordon likes to watch too — her camera observes men watching: men who steal glances, men who leave the theatres with their belts unbuckled, men who turn away in fear when they see a woman enter a sex shop. To celebrate the 40th anniversary of Bette’s cult classic Variety — ahead of a re-release and Q&A at BFI Southbank — she tells me from her New York home: “My film is about the pleasure of looking.”

When Bette first moved to New York City in 1980 and saw the shimmering lights of the pornographic theatre Variety that once stood on the Lower East Side, she couldn’t help but walk closer. “I saw this marquee and it appeared like the most beautiful thing I’d seen. It looked like candy, I just wanted to eat it up,” Bette says. She decided to walk in, snooping around and talking her way into the projection booth. Here, she observed the writhing bodies on screen, but also the audiences watching beneath her, enraptured. She wanted to explore and challenge these layers of looks between the camera, the audience and the women on screen. Inspired by Laura Mulvey’s seminal essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” that situates “woman as image, man as bearer of look” in mainstream cinema, Bette reimagines a film noir that centres the female gaze. She grew up loving Hitchcock’s films, whose femme fatales possessed “a dangerous, magnetic sexuality”, but was more interested in “the idea of reversal. What if the woman was the subject? What if she looked?”

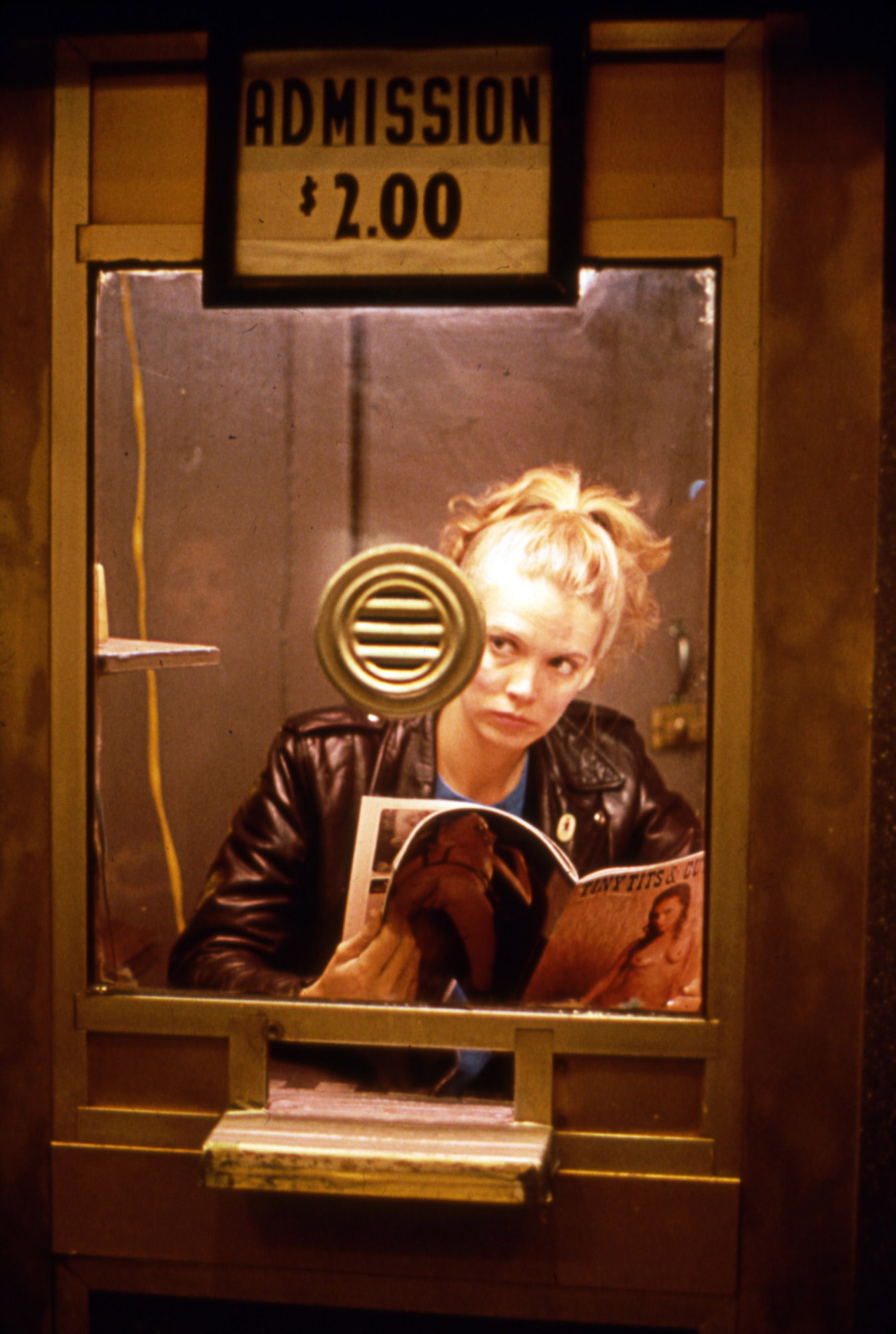

Bette didn’t simply reverse the roles though. Instead, in Variety, which premiered at the 1983 Toronto Film Festival, Christine (Sandy McLeod) is both looker and looked-at. She is tall, blonde and doe-eyed, a perfect Hitchcockian protagonist. Looking for a job to pay the bills, she asks her friend Nan (yes, played by Nan Goldin) for tips. Nan’s heard of something but is hesitant, telling her: “I don’t think you’re the type.” Christine perseveres. The next scene cuts to her sitting behind the ticket booth at Variety, selling cheap thrills to its all-male clientele. The first shot frames Christine from a man’s point of view, observing her in her glass booth like one of the cinema’s attractions. She is constantly framed by windows and doorways, mirroring the framing of the women on the cinema screen. But then Bette’s camera shifts to Christine’s point of view, looking out from her booth, following her as she wanders into the screening room to sneak a look at the women engaging in pleasure. “We see a woman look at the way cinema looks at her,” Bette explains.

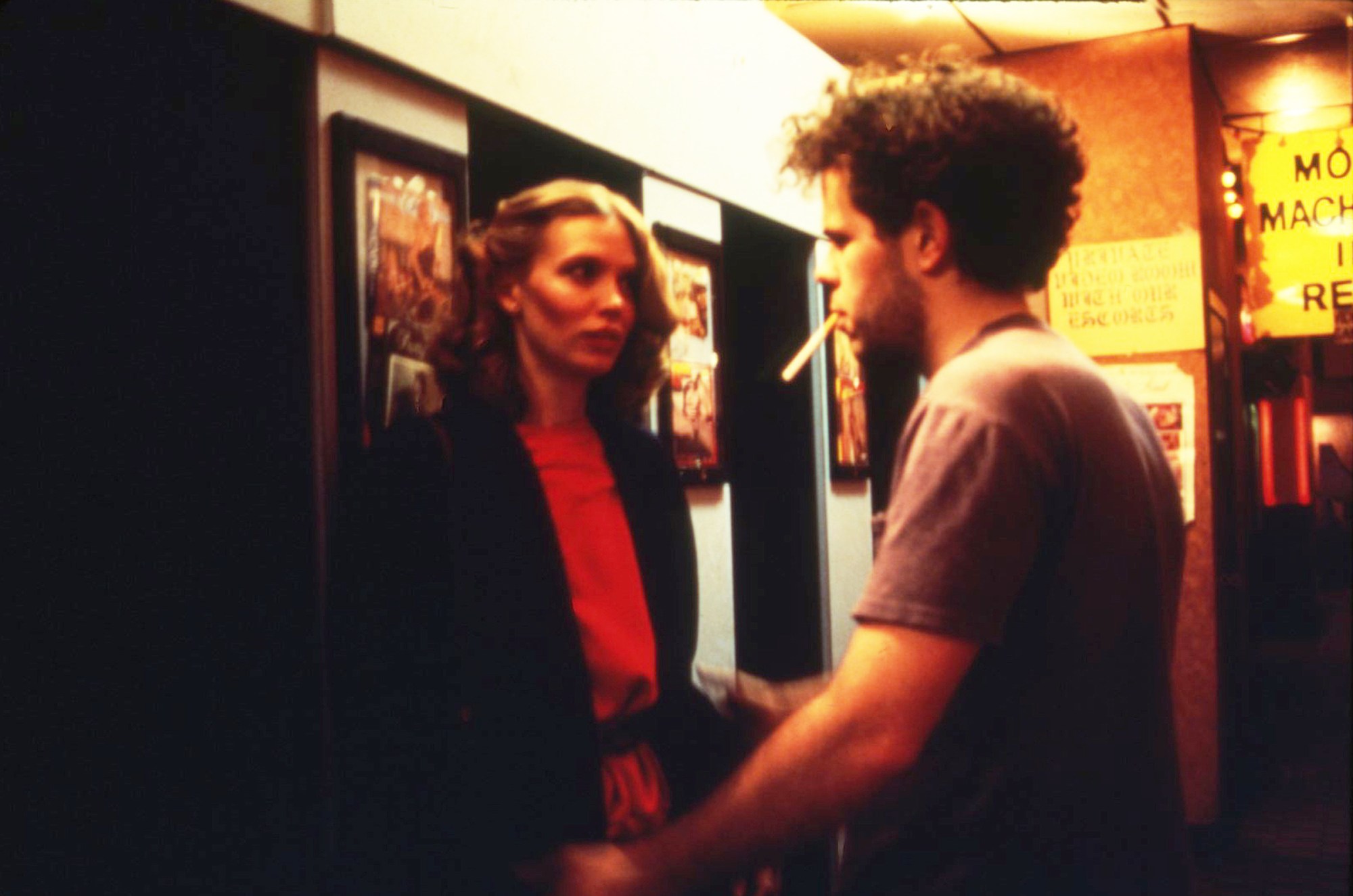

As Christine observes the attendants, she becomes drawn to a returning customer, Louie (Richard Davidson), a Michel Piccoli-type in an impeccable suit. When he asks her out then leaves their date abruptly, she decides to follow him through the night. Stepping away from her expected position as the pursued, she instead becomes the hunter, following her desires with an obsessional fervour. We see Christine enter typically male spaces, as she tracks Louie into a smut shop, a motel, a nocturnal night market where he conducts his under-the-table business. Men react with varying degrees of interest and outrage to Christine invading their spaces. “When I entered a sex shop, the manager asked me to leave,” Bette says of her research for the film. “And I knew why… I had caught men in the act of looking.”

Desire and detective work seemingly merge into one in Variety. Indeed, Christine uncovers a crime that her vanilla journalist boyfriend Will (Mark Paton) constantly boasts to her about already having solved, one that happens to involve Louie and the mafia that operates the fish market.

In a scene where Christine sneaks into Louie’s motel room and searches through his bag, she finds both a journal with Louie’s contacts and a porn magazine. In a Hitchcockian twist, she leaves the diary, the evidence of his crime and instead, takes the magazine. Men and their business are not our concern, instead their narrative hinges upon Christine’s attention. “It’s a quest not for power, but for desire,” Bette argues of her motive. But is there a difference?

As Christine discovers her own sexuality, her sense of fantasy and reality begin to merge. Kathy Acker’s screenplay experiments with incantatory pornographic monologues that Christine delivers to her journalist boyfriend. He squirms and ignores her, focusing on his pinball rather than engaging with her story of a woman who fucks a snake, then a tiger, while a man watches. He’s shocked at a woman not only speaking about sex, but imagining it on her own terms. As we listen to Christine’s story, we become implicated in the visualisation of her desires, complicit in imagining with her. Kathy’s script brings the viewer into stark realisation of our position as voyeurs, watching Christine and watching with her, as Bette slyly looks to us for our response.

Kathy and Bette co-wrote the film during the “Sex Wars” in 80s America, which divided feminists into anti-porn and sex-positive, or “pro sex”, camps. “There was a movement against sexuality. There was a sense that if you had pleasure, you were complicit with the enemy,” Bette explains. “I wanted to challenge that and look at what pornography could offer us in terms of our own desire and imagination.” Bette and Kathy were part of the punk avant-garde No Wave movement, one rife with experimental collaborations between filmmakers like Beth B and Jim Jarmusch; with musicians and artists including Sonic Youth, John Lurie and the aforementioned Nan. “We had no money,” she says. “We were meeting each other in clubs and making stuff together. Everyone wanted to make films and art and we were driven by that, not the market. Not that they would want our films.” Throughout Variety, we gleefully see Christine speaking to familiar faces: Nan, Cookie Mueller, women who describe their desires and their sex work with humour and irreverence.

At the apex of Christine’s obsession, her sexual fantasies of Louie start to project themselves on the theatre’s screen and we witness Bette’s remarkable ability to rewrite even the most misogynist of genres. Bette grants Christine the agency to command the image of her own desire. Rather than imagining their bodies naked and entangled, Christine projects her and Louie’s faces and their exchanged gaze in close-up. Bette also refuses to dissect the female body into its fetishised parts, unlike mainstream cinema. Instead, she alludes to the anticipation before their first touch. “Porn substitutes the touch for the look. You can look but you can’t touch. Gratification in porn is promised but never found. Instead, it keeps you in a state of desire,” Bette says. “I wanted to explore this desire that pushes you on.”

When Christine finally loses her patience and calls Louie, she confesses to stalking him, and surprisingly, he agrees to meet her. However, the anticipated climactic moment of release never comes. Instead, we are left with an image of a dark road lit with a single streetlight before the credits roll. Audiences at Cannes were shocked — some displeased and unsettled by their unfulfilled desire. “Variety forces the audience to use their own imagination to feed their desire,” Bette says. “Cinema is about desire, how it grips you and makes you want more. That’s what I wanted to achieve.”

Variety will be screened on 11 August at BFI Southbank, followed by a Q&A with Bette Gordon. Tickets available here.

Credits

All photography Nan Goldin