Seven Asian women attacked in two hours. Three Asian women shot at a Korean salon. Asian woman fatally shoved to death on subway tracks. Asian woman found dead in Chinatown apartment, stabbed over 40 times. Asian woman stomped on and punched more than 125 times, called an “Asian bitch”. These are but a few headlines from 2022 alone, only one year after eight people – seven of whom were Asian women – were gunned down at different Asian spas in Atlanta.

In a deluge of violent headlines that are faceless to most but aren’t for Asian women, it can be difficult to feel anything but mournful, fearful and wishful for seclusion from a greater public that does not value you.

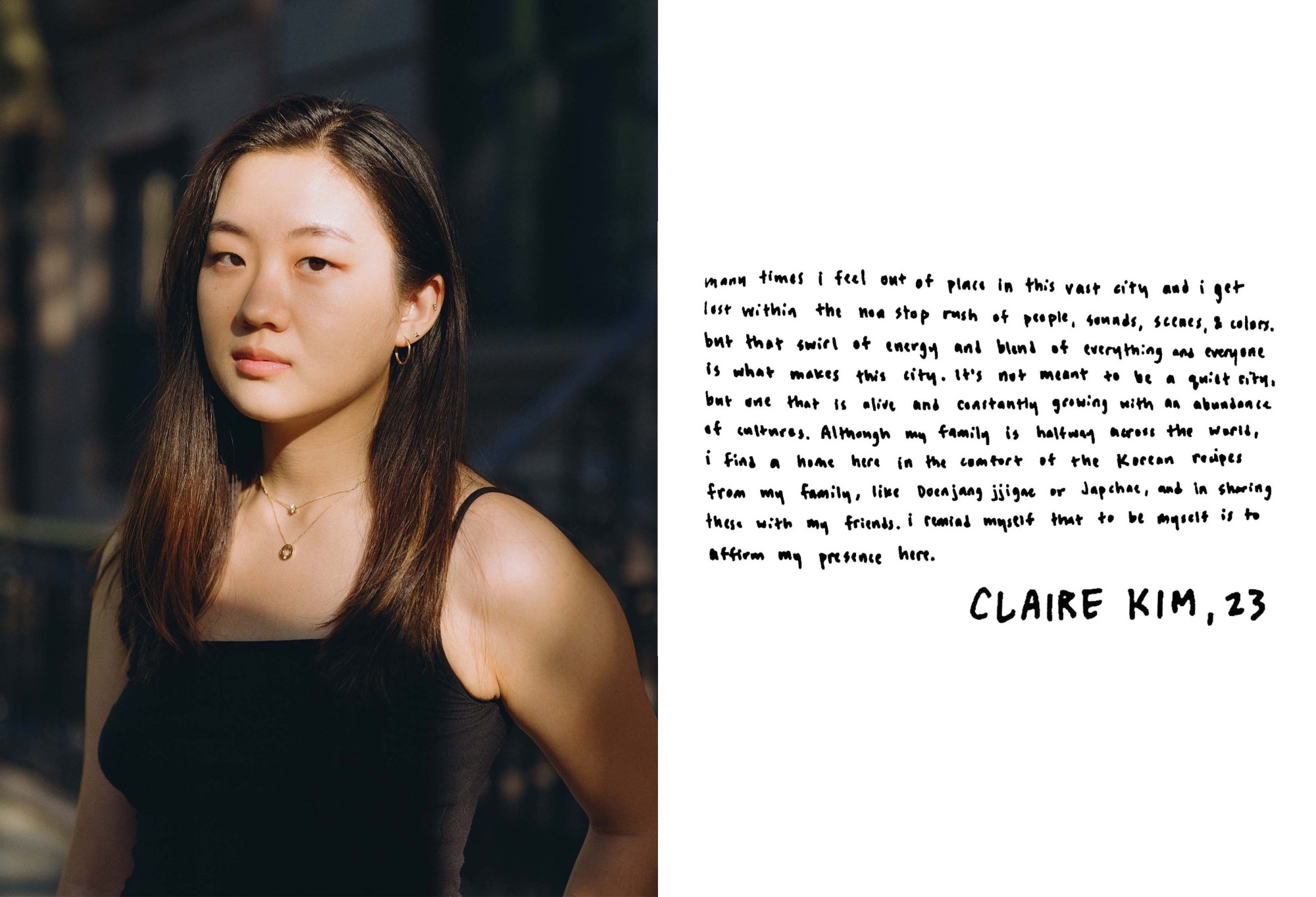

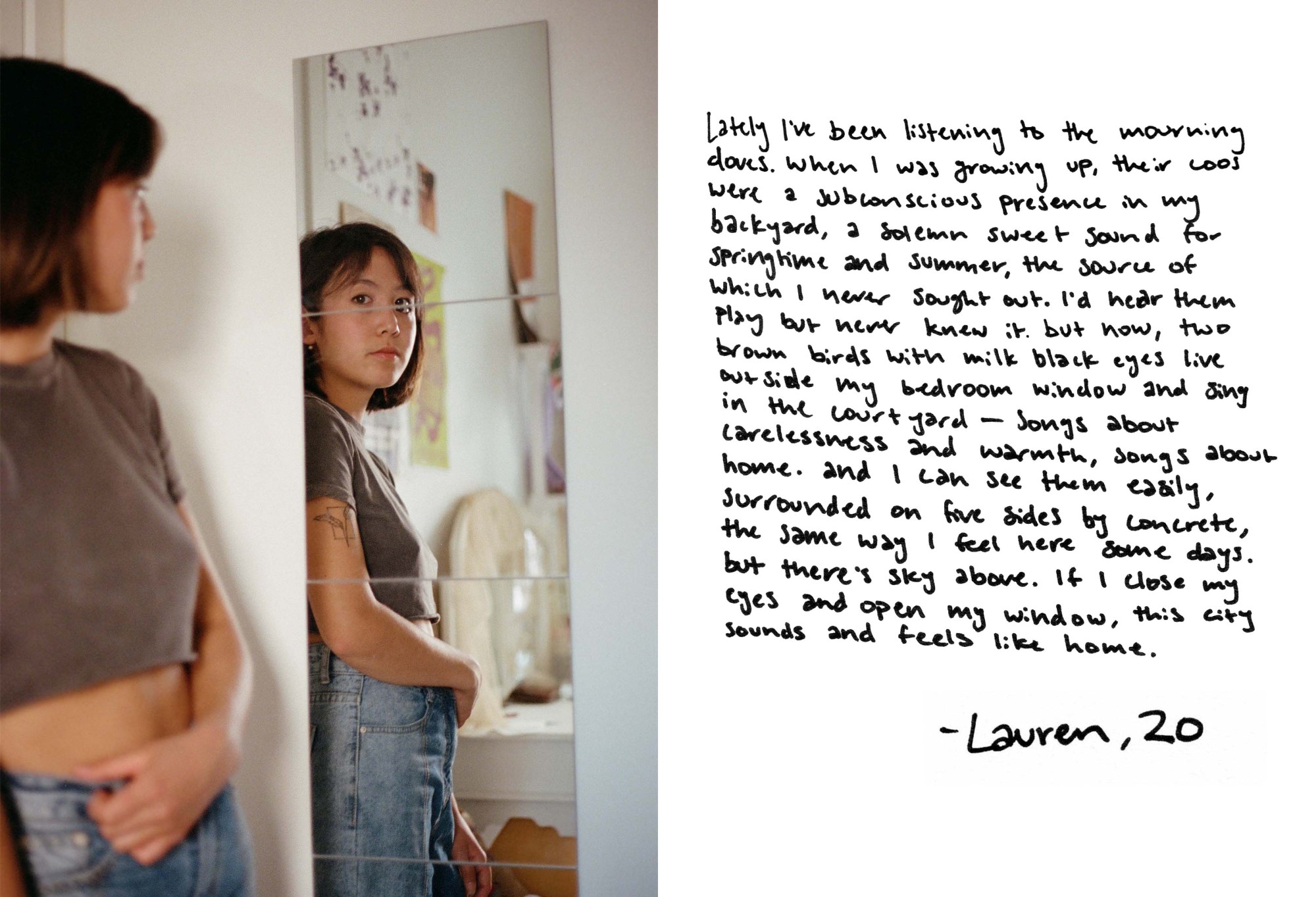

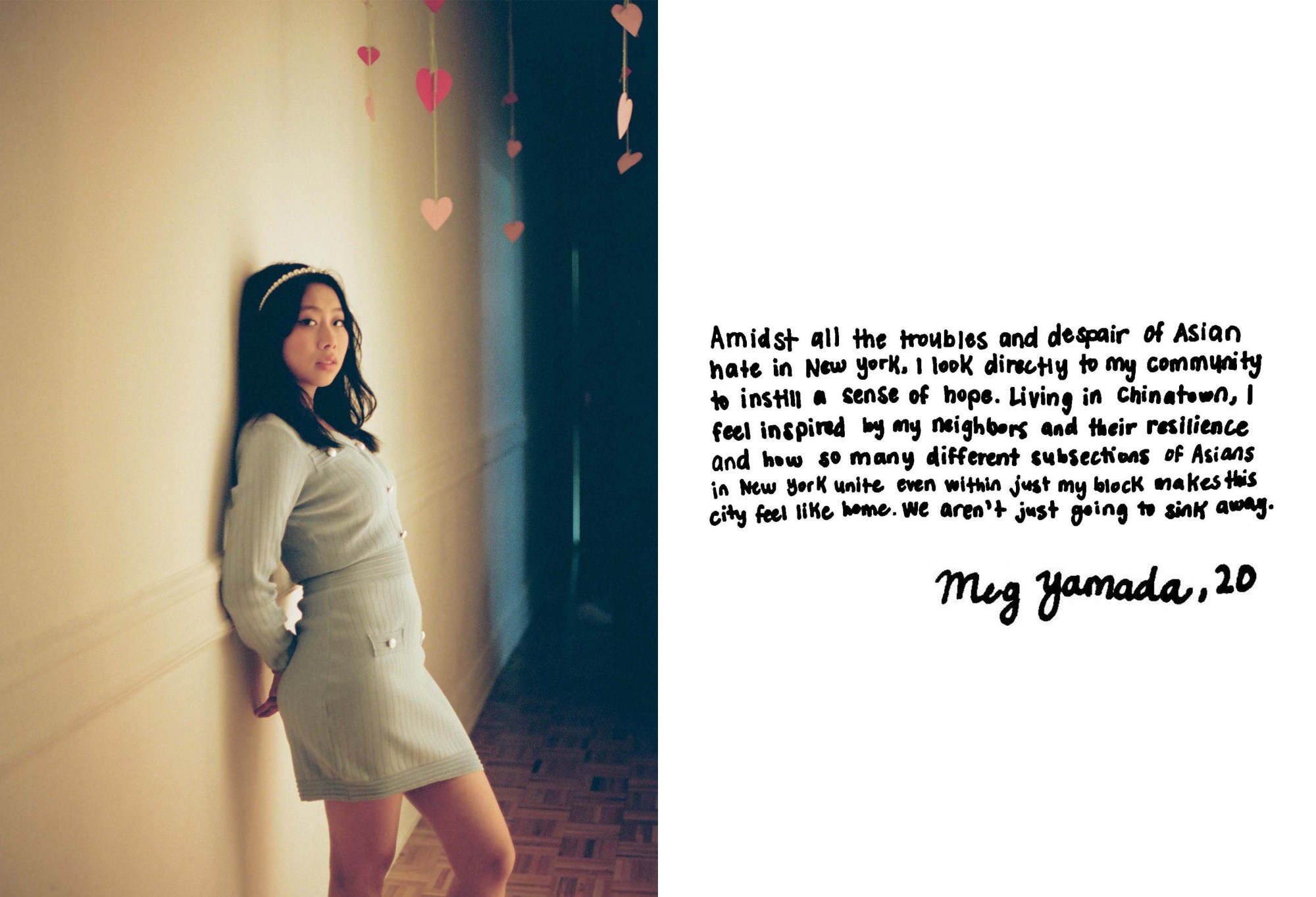

For New York-based photographer Chloe Xiang, her art has become grounds for synthesizing healing and community. Her photo series “The Moon Glows the Same” centers young Asian women living in the city – which reported last year a 361 percent increase in anti-Asian hate crimes since 2020 – and how they are navigating being disproportionately affected by anti-Asian racism and misogyny. They are photographed in the places they have made their homes and are afterwards asked to write a response to the question: “How do you reclaim a city that tries to turn you away as your home?”

“From a personal perspective, I had never done a series that is dedicated to Asian women and femmes, and I think it was due time that I have. There was definitely a big push for me to do this project because I had grown up for so long seeing photographers — especially white photographers — use Asian women in such a fetishizing, voyeuristic lens. I was super fed up with that depiction of Asian women, so it was really important that I talk to my friends and people that I know,” Chloe says. “I wanted to capture the idea of finding home in a space that doesn’t necessarily want to be your home, and yet still pushing through that.”

Chloe hopes to thwart Asian women’s misrepresentation in the media and thus in the wider public imagination. The coalescence of Asian women as highly fetishized subjects in the media and highly targeted subjects for racial and misogynistic violence in real time only shows how deeply ingrained it is in the culture that Asian women are voiceless, or rather silenced, and have no autonomy. This motivated Chloe to ask for the handwritten thoughts of her subjects as a means of reclaiming space and amplifying their voices.

“Asian women are always seen as docile and not having a voice, so I feel like people think it’s easier to gaslight [us]. For me, the written voice is especially essential when I’m talking about reclamation because while I can capture their style and I can capture where they live, I can’t necessarily capture how they think or what they observe themselves,” she says. “Their written responses add another dimension to the photos and show how each person, in small anecdotes, interacts with the city. Handwriting says a lot about who we are and it gives them a physical space to present their voices.”

Chloe’s emphasis on how New York informs her subjects’ identities also reveals how New York in turn is informed by their identities and cultures. It’s ornamentally evident in the city’s different creative industries and it’s materially evident in the gentrification of Manhattan’s Chinatown. More than a neighborhood and ultimately more than a racially constructed category of identification, Chinatown as a multi-generational home and safe haven is no longer safe for its Asian residents and other Asian New Yorkers. It remains a transient destination both physically and in the imagination of those who seek some illusion of an Orientalist aesthetic — and oftentimes, it’s Asian women who are used as the vehicles for its delivery and are told it’s a compliment.

“There is such a contradiction, especially with men, on how Asian women are viewed. On one hand, they use Asian women in their photography and put [us] on T-shirts and weaponize Asian cultures as a [single] aesthetic to partake in voluntarily, but exclude themselves when it comes to protecting Asian women and speaking out against the injustices we face,” Chloe says. “If you’re a white male [creative] and you’re not going to do anything to protect Asian women, then you do not need Asian women or their cultures in your work to benefit you.”

For Chloe, this photo series has become a fundamental basis for channeling her voice, cultivating community and finding time to slow down. It has become a return of personhood to Asian women in a country that has been stripping them of their personhood and autonomy since the first Asian women immigrated here in the 19th century.

“Art has really helped me process what we’ve been going through. Photography allows me to focus in on moments in a world that is so noisy and complicated,” she says. “I wanted to show people with this series that this is how I see Asian women and they’re not these exotic creatures; they’re literally people, real women. It allowed me to have a lot of conversations I’ve never had with the people around me and so many of us are struggling with what’s going on — always on edge, checking yourself and your surroundings, never really feeling safe in your own body. I wanted to tell other Asian women that they’re not alone.”

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more photography.

Credits

Photography Chloe Xiang