This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Post Truth Truth Issue, no. 357, Autumn 2019. Order your copy here. For some, painting is the use of space to make time; the act of capturing a single second, a gesture, a fold, a patch of light, and working it brushstroke by brushstroke until a single instant on a canvas expands beyond its parenthesis into the hours and weeks of lived life. The portraits of Delfin Finley are so saturated with time, so layered with light and colour, with the emotional charge of objects, that an image of a single person becomes an entire landscape. The subjects in his paintings are caught somewhere between the sparse, abstract interior of his studio and the city of Los Angeles that surrounds them. A runaway streak of sunbaked yellow from a mural that overlooks a parking lot, somewhere south of the 10, sits on the surface of one portrait, threatening to envelop the sitter. Skin holds the patinated glare of freshly waxed metal. Colour and light grow interchangeable as if seen through the dim watches of slow shutter speeds when the highway transforms into pure lines disappearing into darkness.

Often, his portraits grow so dense with reality that objects suddenly materialise as if from the void – a stool or a shovel or a noose; a bit of foliage that creeps out of shadow towards the patch of light caught in the skin of his subject. Delfin’s paintings are psychological interiors where all of life, black life, rushes in, personal and highly specific to the city that formed him. “I am who I am,” Delfin says, “because I was raised in the melting pot that is Los Angeles. I’m a product of two completely different environments – The Westside and South Central.”

Delfin was born to two fashion designers in Los Angeles in 1994 during one of the golden eras of street art. On casual walks around his neighborhood with his father, he saw the work of El Mac and other legendary muralists and graffiti artists. “I was extremely inspired by the artists leaving their mark on the streets of my neighborhood. When I moved from private school to public school, I became completely immersed in the graffiti scene. Once I met the kids that were actually going out and doing it, I was hooked.” Most importantly for Delfin, these artists shared a faith in the power of painting to give mythological force to the everyday life of a community; that one could move from the local to the universal, rather than the other way around. “Visiting gallery openings was a weekly ritual. That early experience affected my taste and decision making in my current work. I definitely notice instincts and sensibilities that I wouldn’t have developed if I went straight to oil painting and never explored the graffiti world.” Moving back and forth between different scenes, he learned very early in his practice that a canvas was as willing a surface as a skateboard deck or album cover, or how a long stretch of stucco at the edge of an intersection could be the equivalent of a gallery wall.

In fact if not for the impact of his older brother, Kohshin Finley – a gifted painter in his own right – Delfin would likely have continued working as a graffiti artist. “When I was finishing up high school, my focus was still mainly graffiti, but I noticed how much art school was helping him advance his artwork. It made me want to give painting a try. I immediately became obsessed.” Delfin retained a belief in the folk power of painting when he entered art school, and he began to see the possibilities of mixing the local art that he saw around him as an adolescent with the personal and emotional resonances of portraiture. “I paint the people closest to me, they come from all walks of life,” Delfin says of his subjects. In many ways, all of these figures constitute a single artistic milieu, a moment in the history of West Coast culture, and Delfin has become one of its most acute poets. If he’s able to capture some essential condition of his subjects, it is because he is one of them.

The work usually begins with a conversation in the studio. “We speak about social injustice, prejudice, and racism. This definitely affects the person’s expressions and demeanor.” He then takes hundreds of photographs documenting the effect of the conversation on his sitter. These images are collaged together to find a moment that captures some essential quality of their exchange, only then does he turn to drawing and painting. The paintings always begin with the eyes. “I feel like the eyes are the biggest indicator of likeness. Getting the likeness down is extremely important as who I’m painting is usually someone that has a pretty significant role in my life,” the artist says. And yet it is in the unrelenting effort to capture a likeness that Delfin is able to move into deeply abstract and emotional territories.

In Not in a Month of Sundays (2017), Tyler, the Creator sits on the floor of a featureless interior in a state of suspension between comedy and tragedy, buckling beneath the weight of a life spent under the spotlight. These are the harried performances of everyday life that even the most famous of black men cannot escape. Delfin finds peace in a character known for continuous movement, a creative and physical hyperactivity that usually fills all available space within a frame. He wears a light pink Golf Wang hat and matching jacket, white tube socks and skate shoes. This is oil painting for us by us; black people set in black spaces without the ponderous legacy of European portraiture.

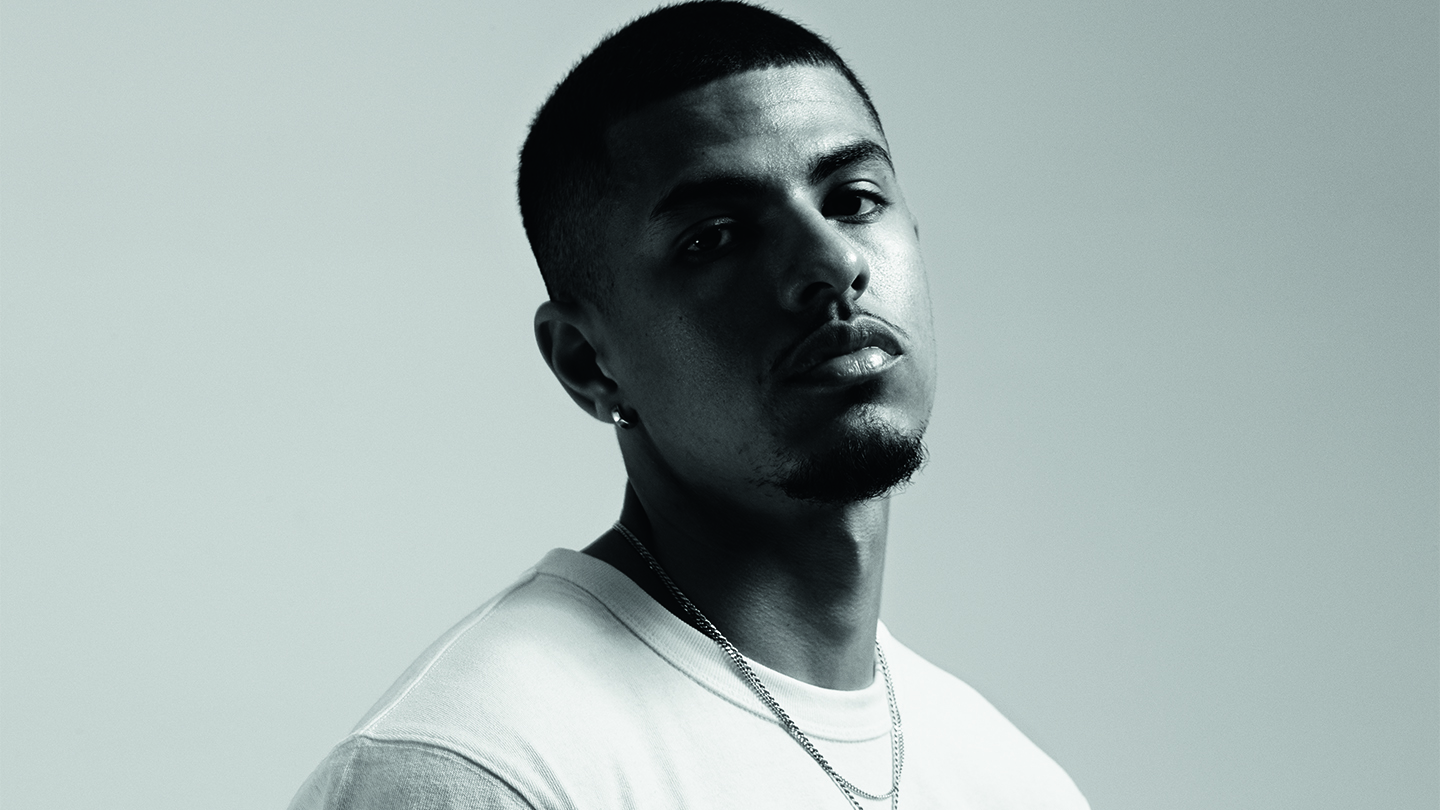

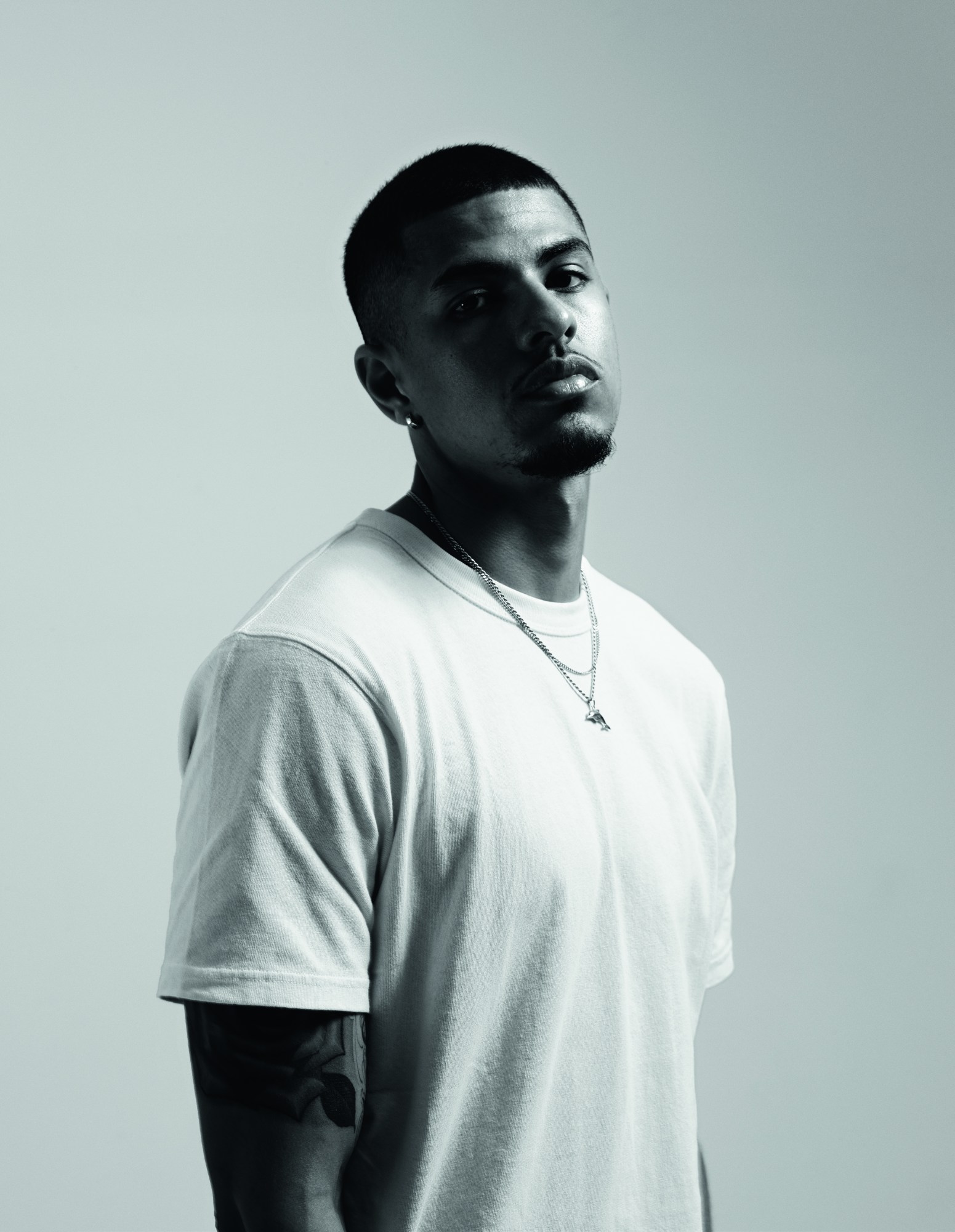

For this issue of i-D, Delfin has painted skateboarder Tyshawn Jones in collaboration with photographer Mario Sorrenti and Editor-in-Chief Alastair McKimm – the three of them worked together on the photo that Delfin then painted in his Los Angeles studio. Although he was unable to have the one-on-one photo shoot and conversation central to his practice, he nevertheless manages to render him near and familiar. As with Delfin’s paintings of other skateboarders such as Na-Kel Smith, as always, the emphasis is on an interior condition.

In one haunting self-portrait, Delfin sits on a step ladder beneath a dangling noose. A light source outside the frame casts strong shadows of artist and noose onto the paintings hanging behind them. This should not be mistaken for some divine chiaroscuro, it is the harsh and unrelenting light of studio photography. The artist is on camera and, as always, the menace of death is not far away. “It represents our history of racism, lynching, prejudice and inequality. I use red, white and blue to reflect on America, land of the free, unless you’re black. I want to represent every person of colour who must carry the weight of their violent history. I’m trying to look ahead, feel empowered to move forward, but never forgetting.”

In a reversal of symbolic convention, to climb the ladder is to move towards death, death by gravity, by being pulled back towards the ground. This is a parable about black life perhaps in which a fear of flight and vertigo constitute the same disorder, and there is nothing to do but remain in an in-between state, a frozen figure like all of Delfin’s figures, in waxwork stillness, in a painting.

Credits

Photography Mario Sorrenti

Styling Alastair McKimm

Hair Bob Recine for Rodin.

Make-up Kanako Takase at Streeters.

Nail technician Honey at Exposure NY using Dior.

Photography assistance Lars Beaulieu, Kotaro Kawashima, Javier Villegas and Chad Meyer.

Styling assistance Madison Matusich, Milton Dixon III and Yasmin Regisford.

Hair assistance Kabuto Okuzawa and Kazuhide Katahira.

Make-up assistance Kuma.

Production Katie Fash.

Production assistance Layla Néméjanksi and Adam Gowan.

Creative and casting consultant Ruba Abu-Nimah.

Casting director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING.