By 1968, the Socrates Sandals shop in Newport Harbor, California, had become a favourite destination for Orange County’s bubbling counterculture. Here, hippies, surfers, students, blue-collar workers, and radicals of all stripes found kinship in the otherwise conservative SoCal town. Driven to document the random encounters he had throughout the day, store clerk Doug Biggert began photographing customers with a Kodak Instamatic.

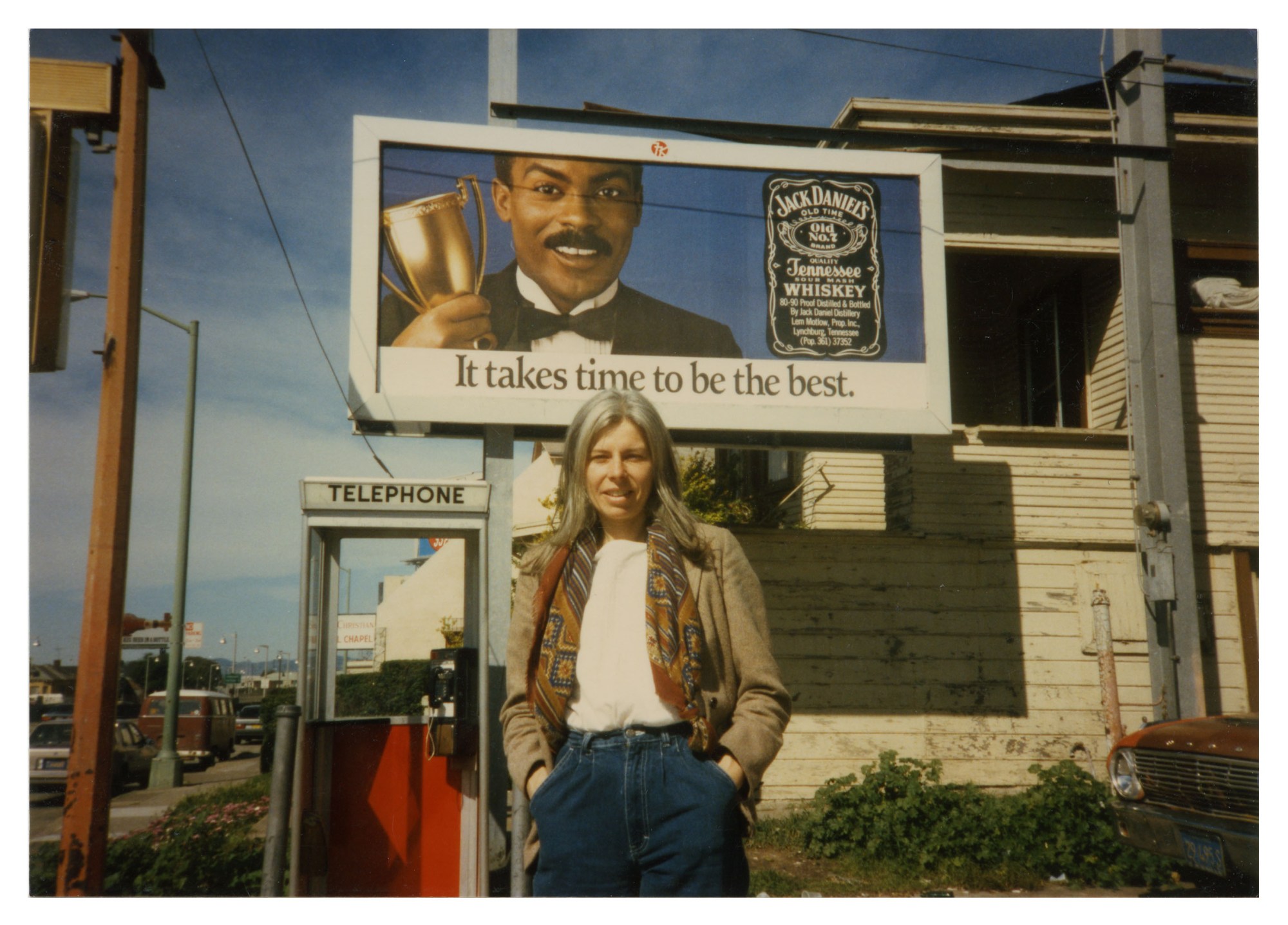

Doug displayed the small format snapshots in the store, which was as idiosyncratic as the customers it drew. Every receipt bore the legend, “Call before you come. We’re not open all the time,” reflecting the go-with-the-flow vibe of the times that Doug embodied. Over a five-year period, he was able to amass some 2,000 portraits, forming a visual record of everyday life in the all-American beachfront town.

By the early 1970s, photography was just beginning to break into the art world, with artists like Walker Evans, Manuel Álvarez Bravo and Bruce Davidson exhibiting at the Museum of Modern Art. Then, as now, snapshot photography was largely overlooked by most — but not by Thomas Garver, Director of Newport Beach Art Museum, who gave Doug his first museum show in 1972.

Thomas Garver paired Doug’s portrait exhibition with paintings by Edward Hopper to show the evolving vernacular of twentieth-century American life. In both their works, the quotidian possesses a casual glamour removed from the trappings of sentimentality, nostalgia or romanticism. “In general, it can be said that a nation’s art is greatest when it most reflects the character of its people,” Edward Hopper said.

Despite Doug’s gift for portraiture, he possesses no pretensions of being labelled an artist. Well versed in photography, Doug recognises a distinction between his work and that of masters like Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander. “He sees himself as a documentarian of culture,” says long time friend, artist, and writer Liv Moe. “Doug connects with people from all capacities pretty deeply. If something triggered him, he was interested in you. No matter where you put Doug, he’s going to end up collecting a bunch of friends.”

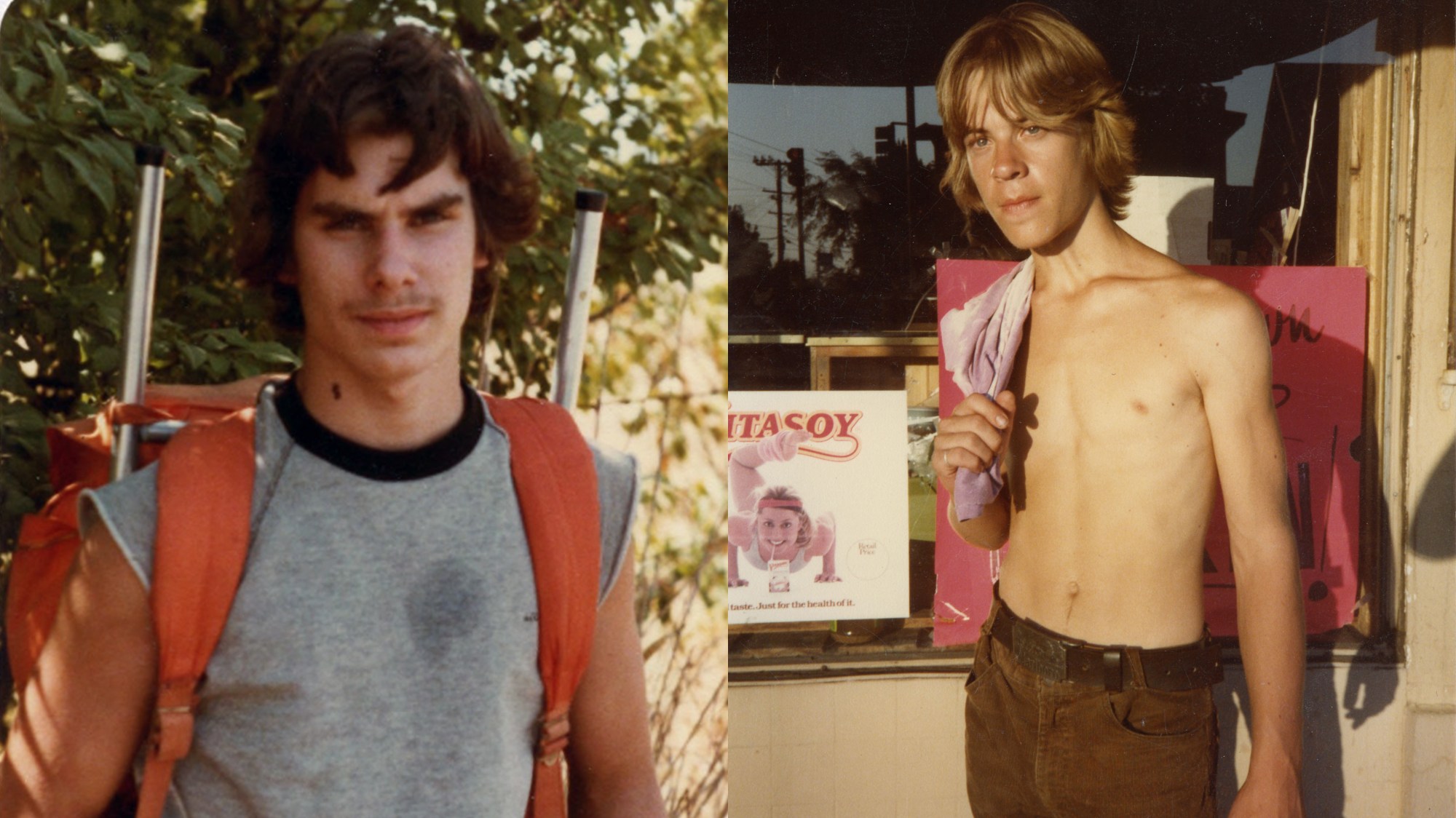

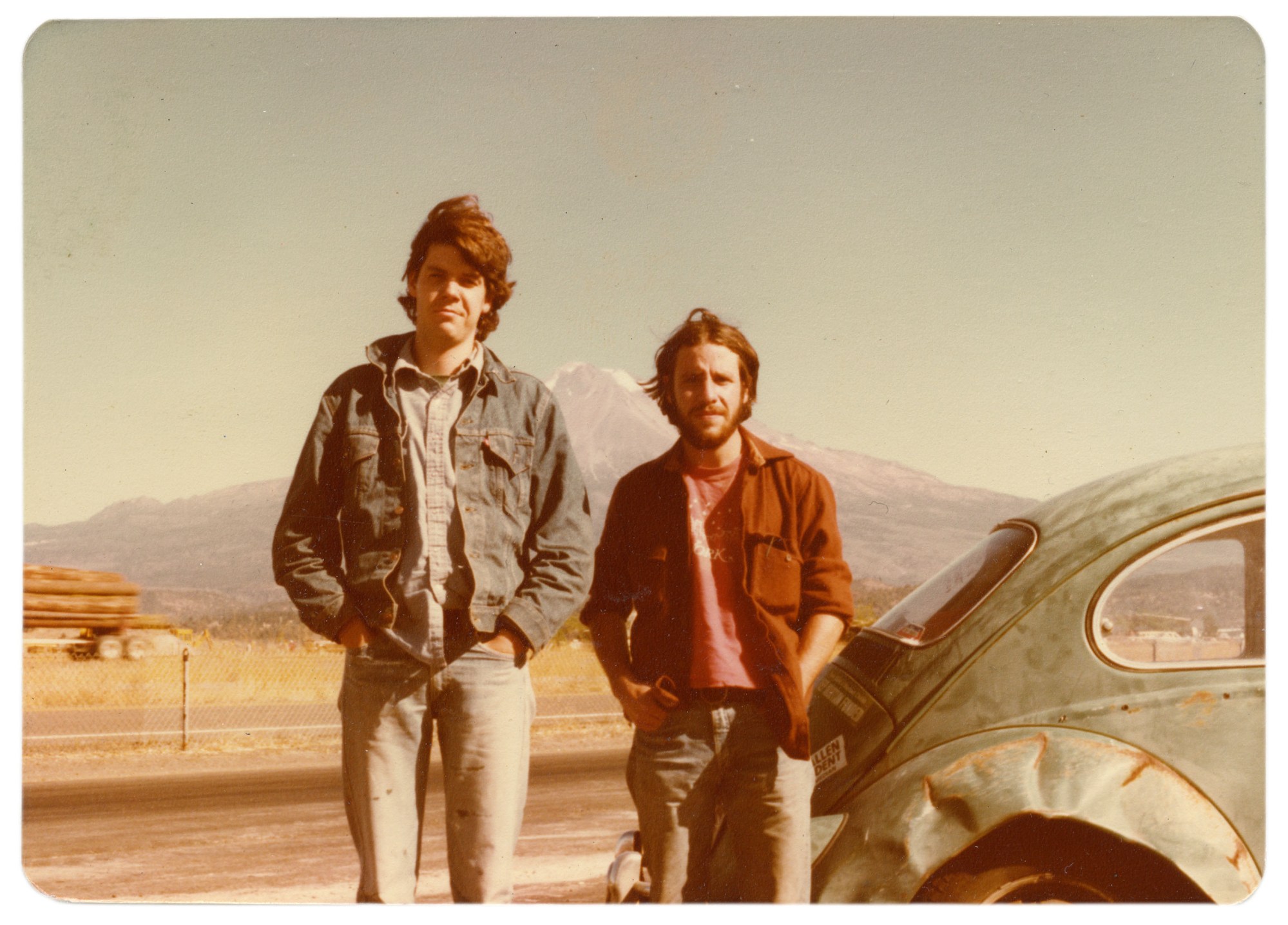

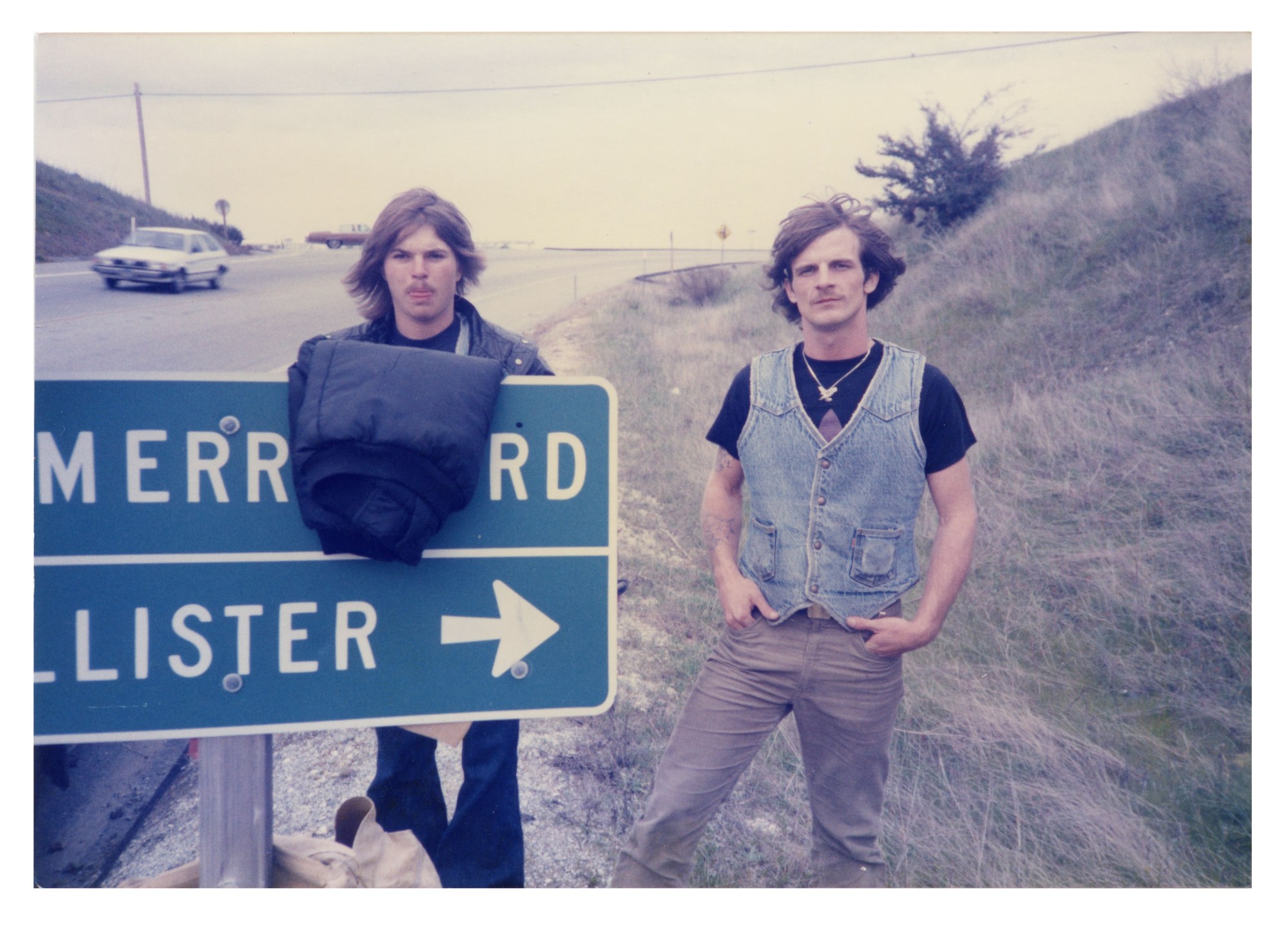

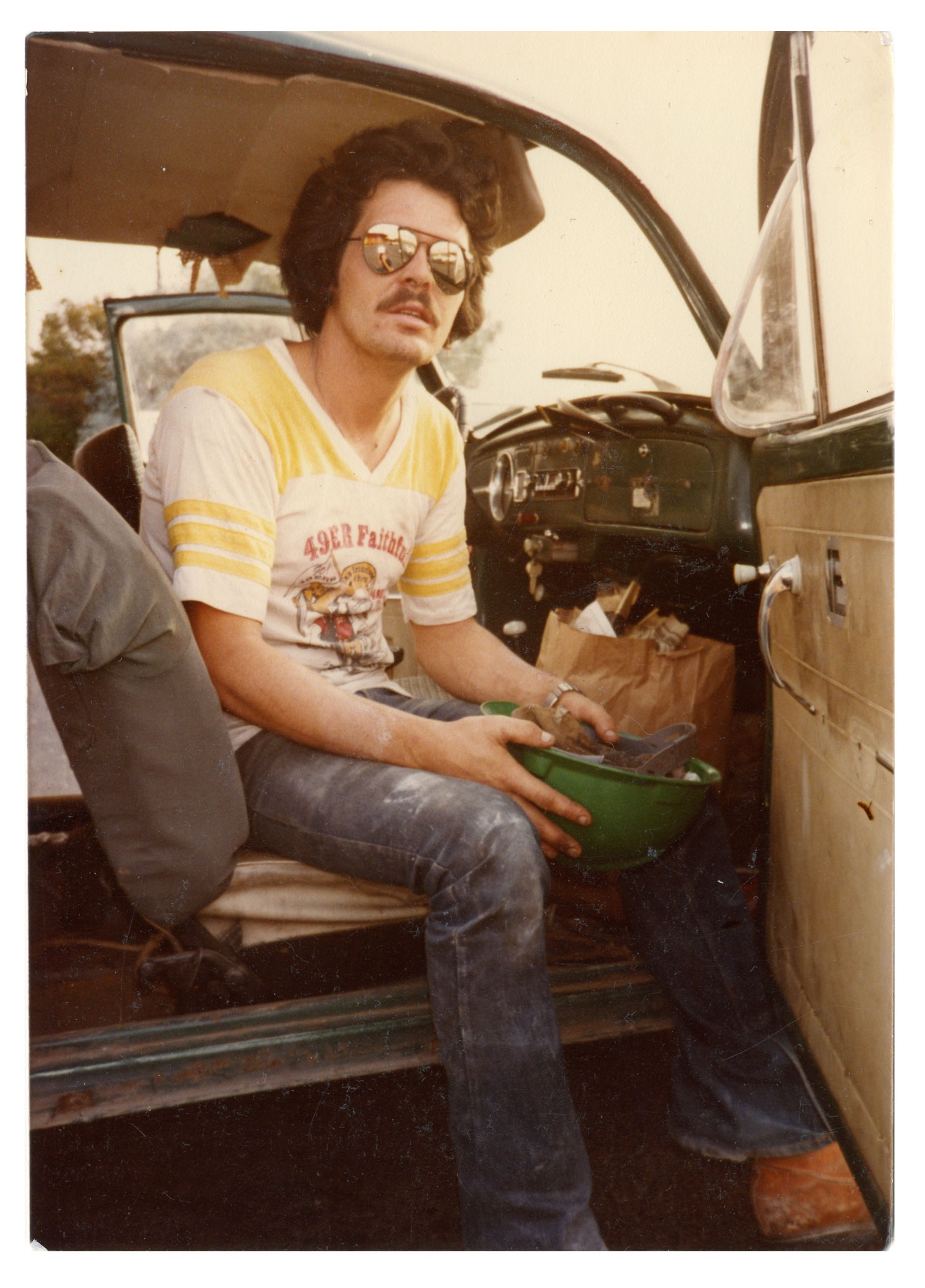

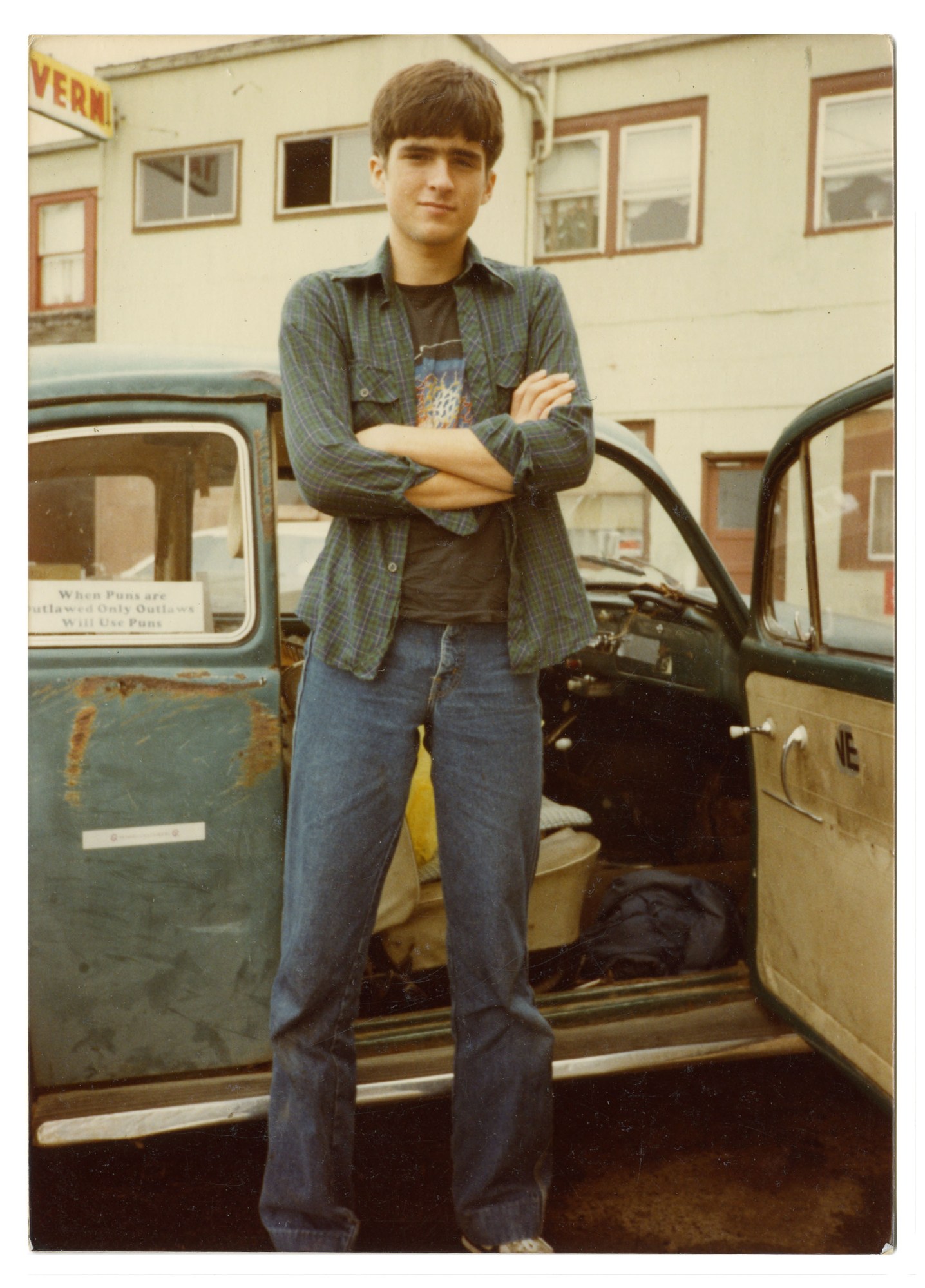

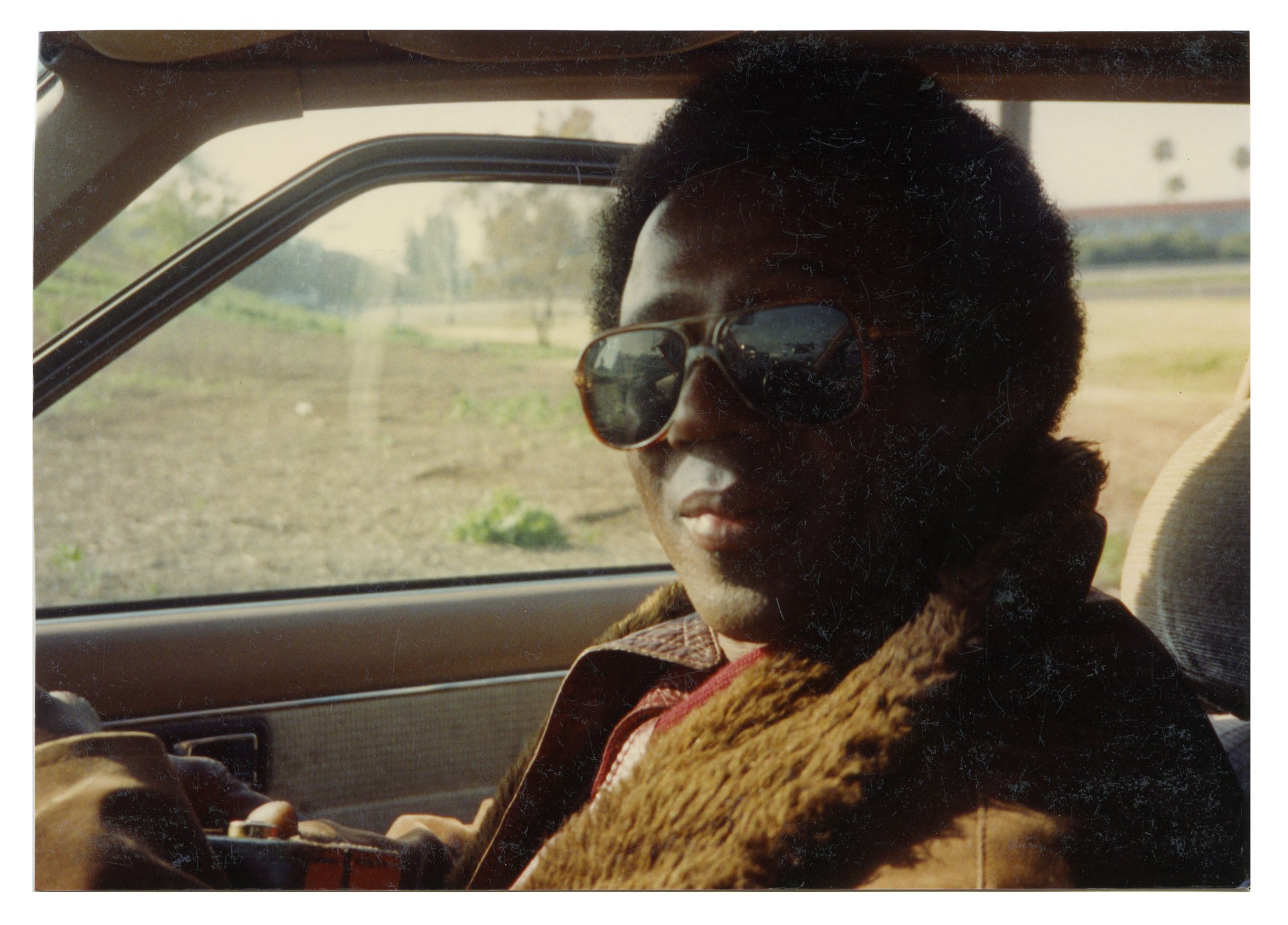

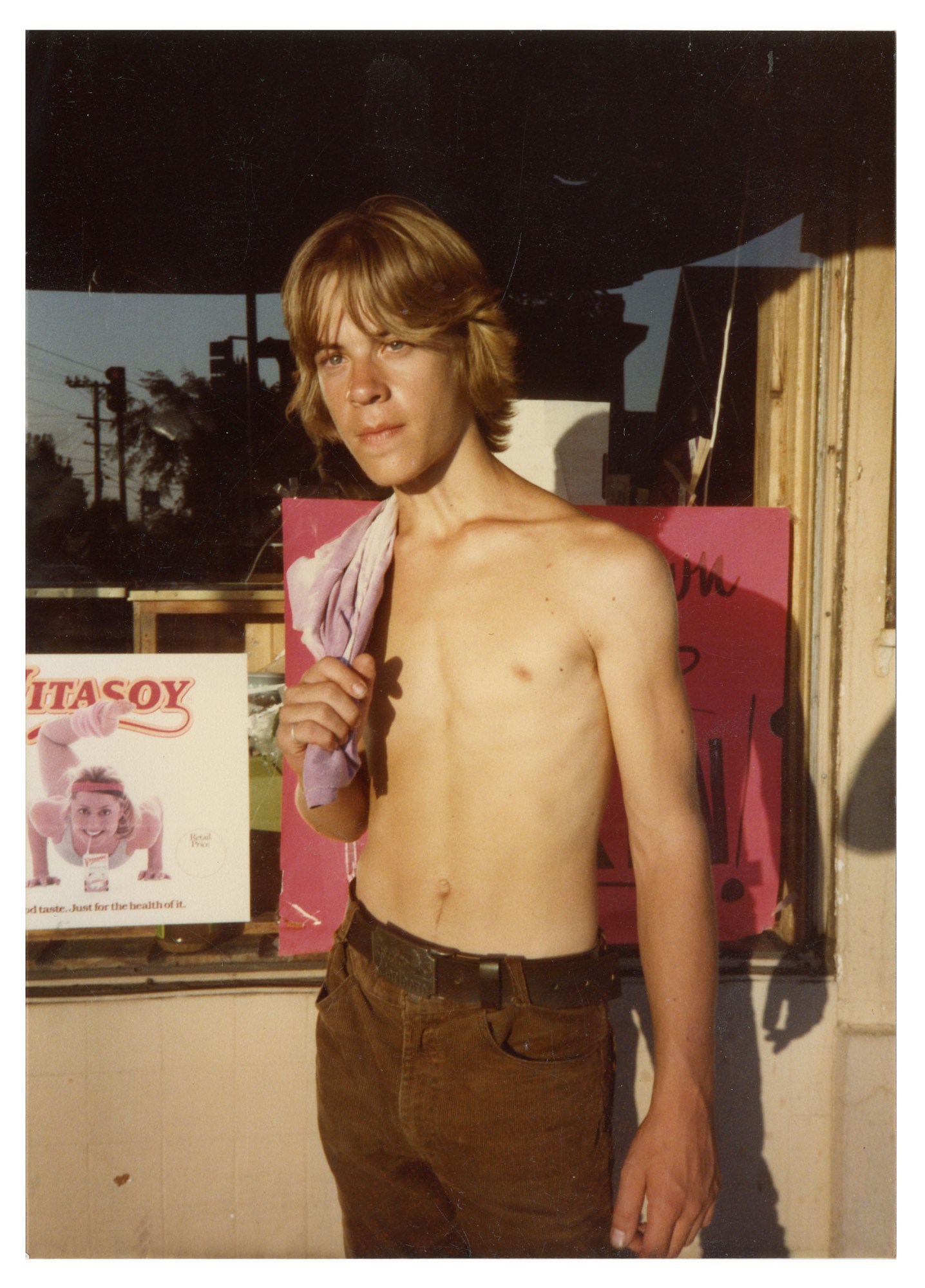

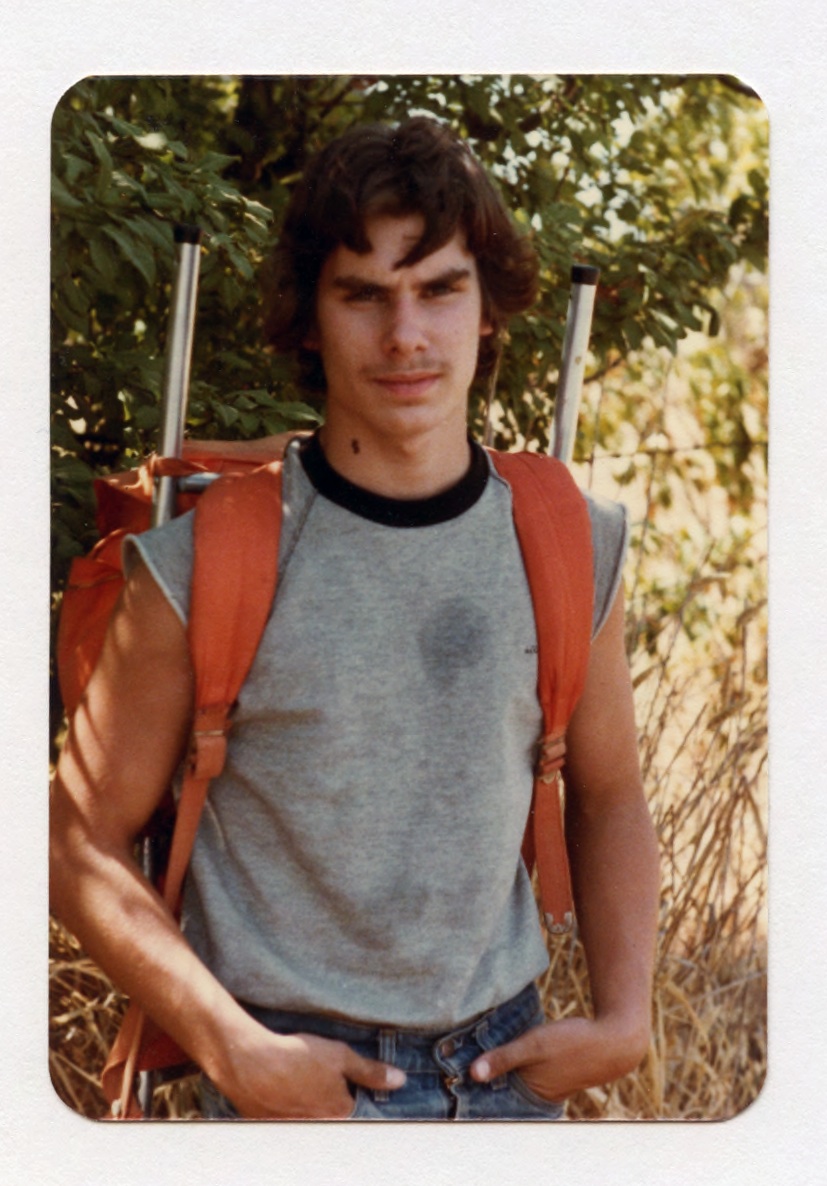

In 1973, Doug began a new series of work photographing hitchhikers he encountered driving his green 1966 VW Bug to a twice-weekly late-night jazz program at KVMR, a radio station out of Nevada City, California. Over the next 12 years, he would create some 450 informal portraits of his passengers: young teens, college kids, tourists, hustlers, drifters, runways, and slackers that offer a revelatory look at America in transition. Now, with Doug Biggert: Hitchhikers and a Sandal Shop, two concurrent exhibitions at George Adams Gallery and Robert Mann Gallery celebrate Doug’s passion for chance encounters with populations that might have otherwise gone unseen.

“Doug sees himself as a participant who is responsible for the things he sees, but does not necessarily see himself in that category himself,” says Liv, who knew of Doug for the work he had done to bring zines to the global stage long before they met in the early 2000s. From 1978 to 1999, Doug worked as a media buyer at Tower Records and Books headquarters in Sacramento. Seeing the potential for magazine sales just as music journalism was taking off, Doug helped set up more than 50 newsstands throughout the highly influential Tower chain.

As indie publishing began to surge, Doug recognised the power of populism in the flood of new voices. Once again drawn to the fringe, he made space for a new generation of zines hitting the streets. Preferring Propaganda to People, Tattoo Life to Modern Bride, Doug became a seminal force in the proliferation of zine culture. “Doug helped fund some of my friends’ zines,” Liv says. “If there was something he liked and wanted to see carried in multiple stores, he would contact the producer, usually a bunch of young punk kids. Since they couldn’t ramp up production, Doug would offer to pay that part, and a lot of people got started that way.”

After Liv and Doug became friends in the mid-00s, she began to learn more about his photographic work — much of which was predicated on his desire to create a living memory. “His mother had memory issues in the later part of his life, and Doug is consumed with the concept of remembering things,” Liv says. “It’s daunting to think about documenting conversations and meetings so that you remember them later, but that motivates Doug. Having those photographs can be really endearing and compelling.”

Taking care to record details on the back of the prints, Doug’s photographs become a time capsule of California’s fringe. “If there is something that really defined Doug from that moment, it’s the counterculture,” Liv says. “But when he talks about the past, he doesn’t do it with much nostalgia. What Doug is most interested in are the people — where they lived, what they did, and what it was like to spend time with them.”

Pointing to the photographs of hitchhikers, Liv says, “Doug was always drawn to underdogs. There was a part of Doug that was driven to look out for people no one else was looking out for. I think that makes its way into the art he was interested in, as well as the way his own work was presented and talked about. Doug wasn’t going to be interested in anything that started to feel like it was putting him into an exclusive club where the people he cared about weren’t going to be welcome.”

Driven to protect his integrity, Doug resists setting himself apart — a stance clearly revealed in every aspect of his work. Whether producing zines for Tower or making photographs of chance encounters throughout his life, he executes his vision on his own terms. “There was a lot of freedom for Doug in eschewing fame and wealth because once you turn that corner, you start worrying about being successful and what people think about you, and you have to maintain that interest,” Liv says. “I think that’s something Doug innately understood, and he went in the opposite direction because he was not willing to make that compromise.”

‘Doug Biggert: Hitchhikers and a Sandal Shop’, is on view through 7 May at George Adams Gallery and 13 May 2022 Robert Mann Gallery, both in New York.

Credits

All images © Doug Biggert, courtesy George Adams Gallery