For over fifty years, Edmund White has been the foremost chronicler of gay life. In his memoirs, novels and essays, the American writer has documented its shifting landscape. In 1982’s A Boy’s Own Story, he wrote about growing up in the repressive American midwest of the 1950s, while City Boy (2009) dealt with the post-Stonewall liberation of 1970s New York. He also spent sixteen years in Paris, mixing with everybody from Yves Saint Laurent to Michel Foucault, as detailed in 2014’s Inside a Pearl.

White’s voice is both gossipy and learned, salacious and sophisticated, and always sharply observant – not least when turning his gaze upon himself. At 85, White has just published The Loves of My Life: a ‘sex memoir’ that doubles as a survey of gay society right up to our present moment of Pride, hookup apps and equal marriage. In it, he writes: “I’m at an age when writers are supposed to say finally what mattered most to them – for me it would be thousands of sex partners.”

I ask White, over a Zoom call from his apartment in New York, what he thinks made him so precocious. “I think there was always a little rebel in me,” he says. “I also was so bewitched by men, as I am now. I mean, that seems to have been a lifelong theme.”

The Loves of My Life is the story of this spell. Readers of White’s memoirs – this is his sixth – will be familiar with some of the characters. There’s Keith McDermott, the actor and “famous beauty”, who swore White to a vow of chastity (“We could sleep side by side as long as we never touched”), and his college lover and “first husband”, Stan. “I was obsessed with him, not sexually but religiously,” White writes. (The two still see each other every week; “he’s doing the supreme sacrifice of reading my entire oeuvre,” White says.) But there are countless others too, including Becky – one of his twentysomething forays into heterosexuality – and Rory, a former student who’s become, according to the book, White’s ‘sexless lover’ and Skype buddy.

Was anything off limits? “Nabokov in Speak, Memory talks about how he’s so reluctant to write about his favourite nanny when he was a child. Because he knows that once he writes about her, he won’t think about her anymore.” Accordingly, White’s husband and partner of thirty years, Michael Carroll, receives only a brief mention.

“We were still standing in the doorway when we started groping each other”

edmund white

Yet – with characteristic candour – White more than makes up for this discretion elsewhere. We’re introduced to the Fire Island “satyr” who leaves him covered in poison ivy stings after a romp in the bushes; the first straight guy he seduced at boarding school, a “glamorous blond quarterback” called Bucky; the “sweet but tiresome slave” he met in the ‘70s, who enjoys a “cheek-reddening spanking” but prattles on about Anne Rice novels; and the redhead S&M master David, who merits perhaps the funniest line in the book: “His dick was large as something that would have saved the lives of three Titanic passengers.”

Yet even at his most lascivious, sex for White is something akin to rapture: a sacred ritual rhapsodised about with religious fervour. It’s far from what White calls a “mechanical and coldly indifferent” transaction one might expect from somebody with 3,000 sexual encounters under his belt. He’s unabashed about his many experiences paying for sex – including the one time he hustled himself – and gleefully turns the pay-for-play power imbalance upside down. “The greatest disadvantage is that respectable people, including respectable gays, disapprove,” he says. “That’s also the greatest advantage.” Does he think Gen Z are more prudish than previous generations? “We do live in this politically correct world. It’s warming up a little bit, but I think that American culture especially goes through cycles of puritanism and then libertinage.”

In the book, White recalls the night of the 1969 Stonewall riots: that seismic moment in the struggle for gay rights. Striking a typically self-effacing tone, he writes that as “a middle-class white twenty-near-year old who’d been in therapy for years trying to go straight”, he was initially disturbed by the uprising of “drag queens and tough kids from Harlem”. Today, he finds depressing the “hateful” attitude towards trans people, who “seem to outrage 99% of Americans.”

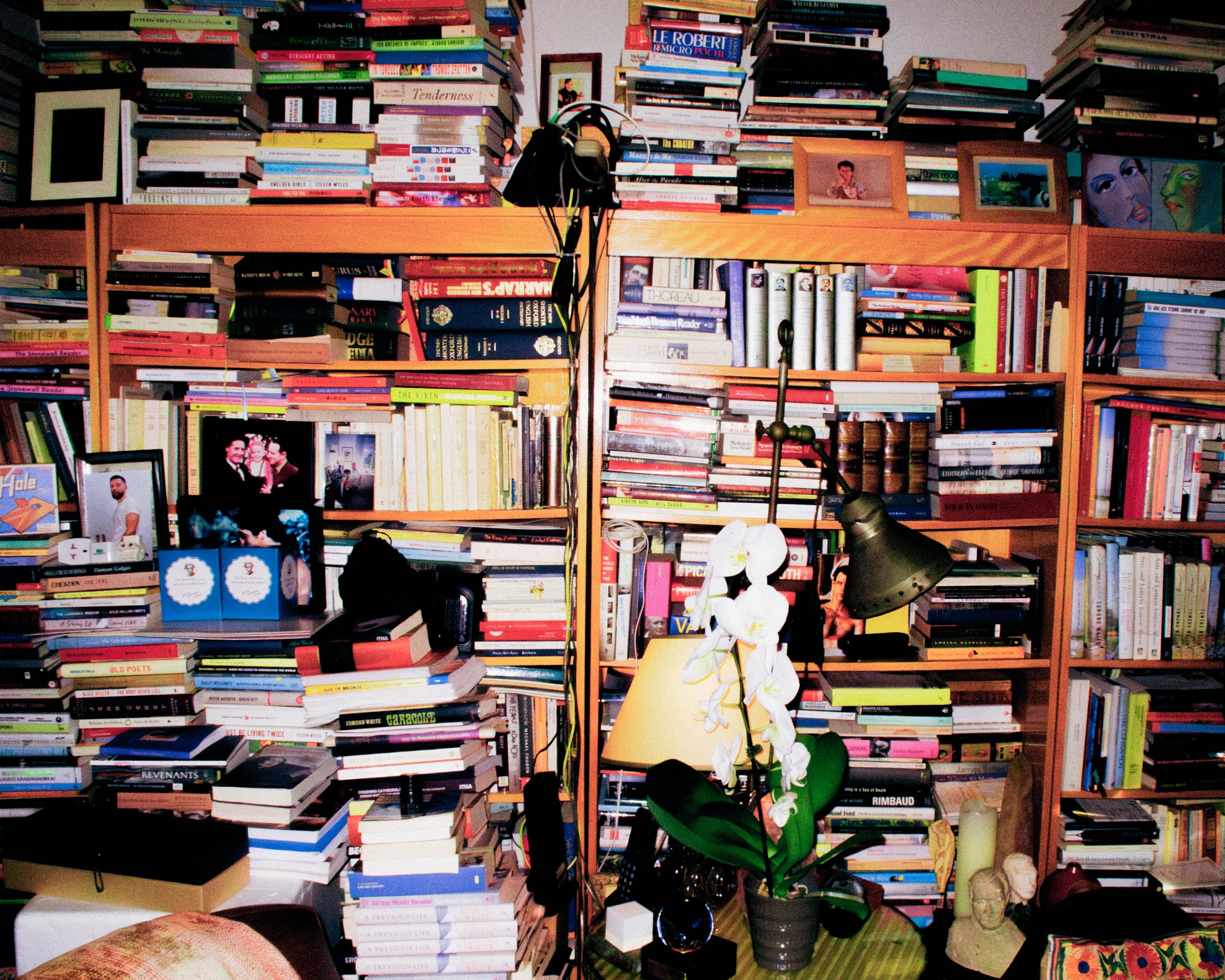

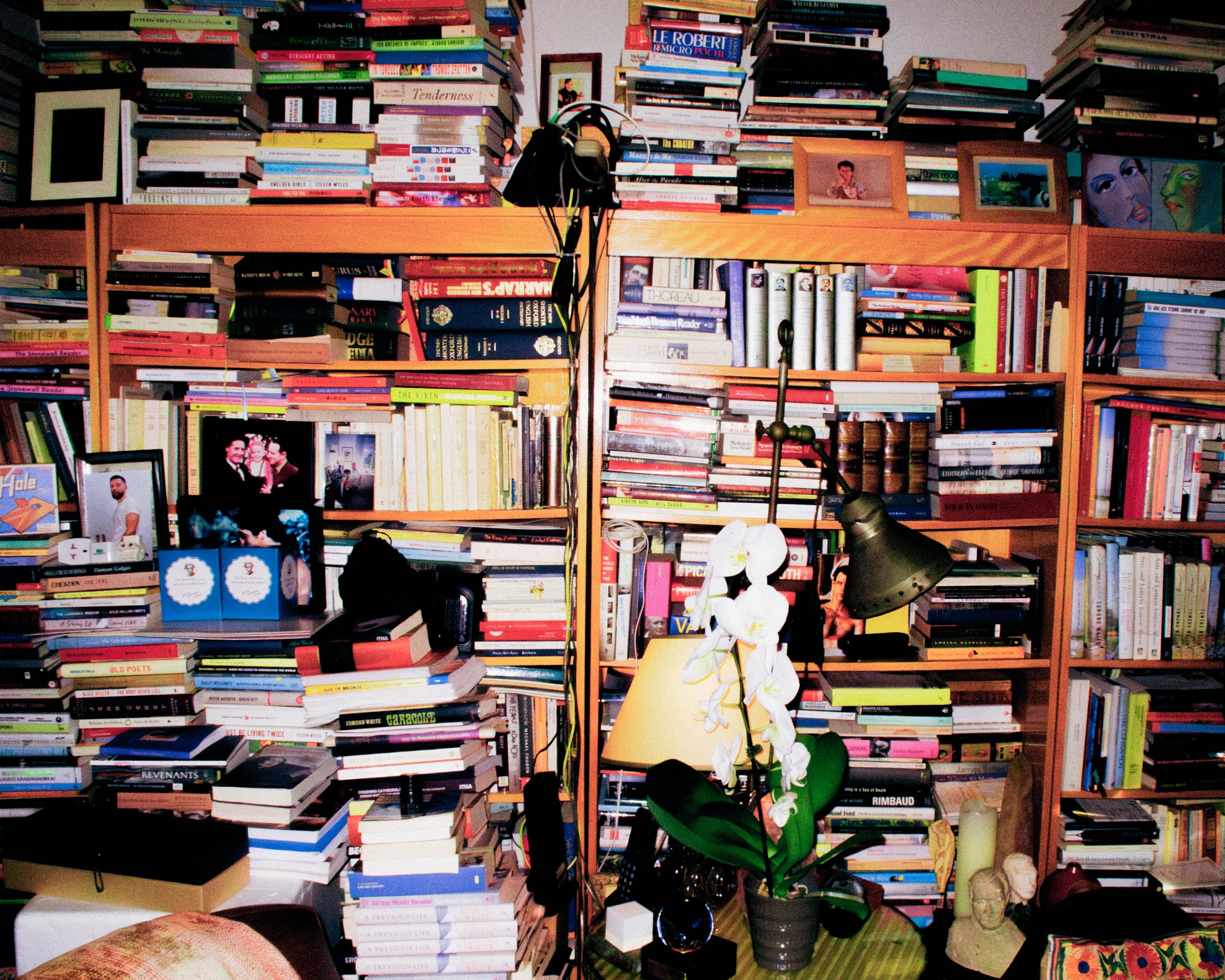

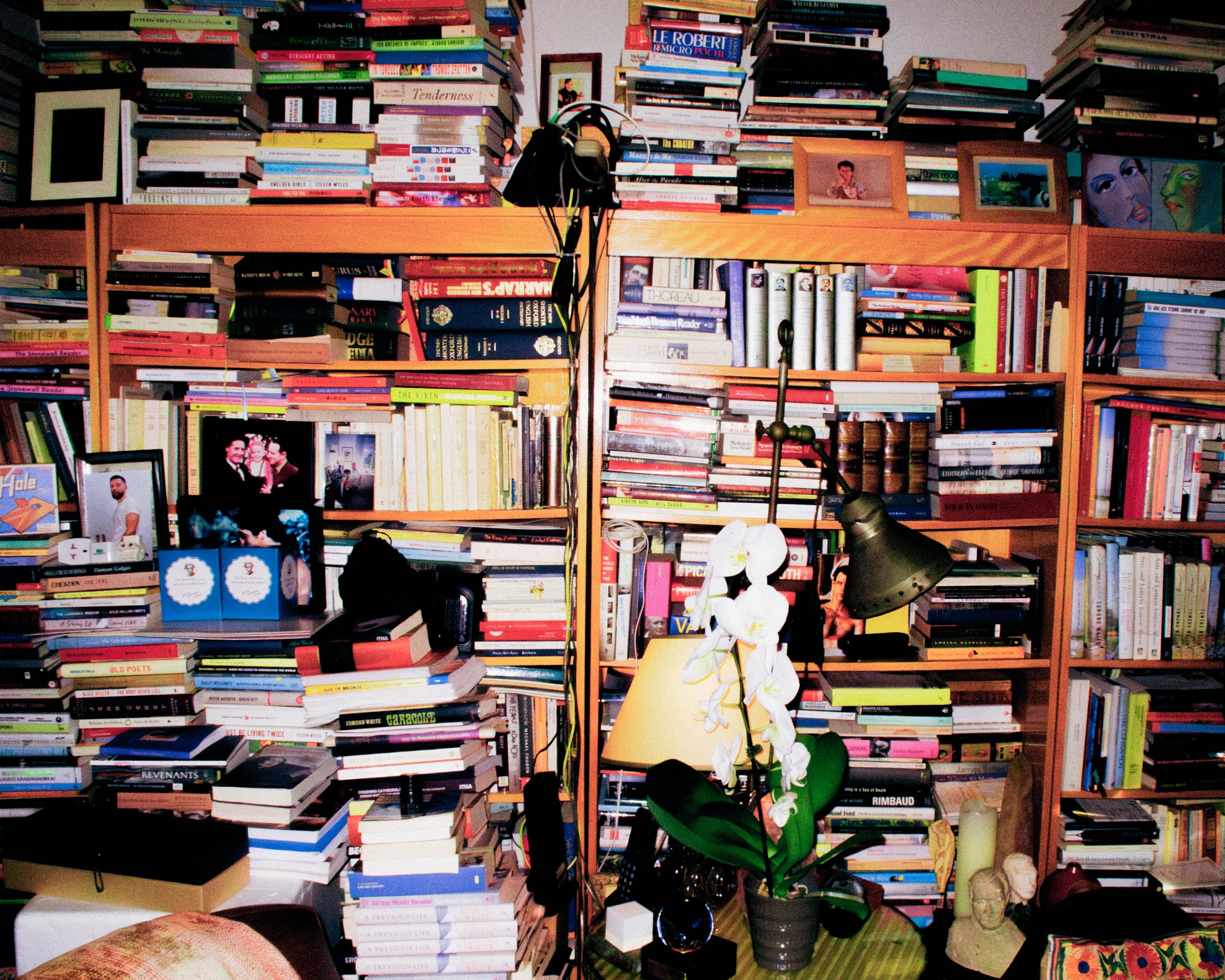

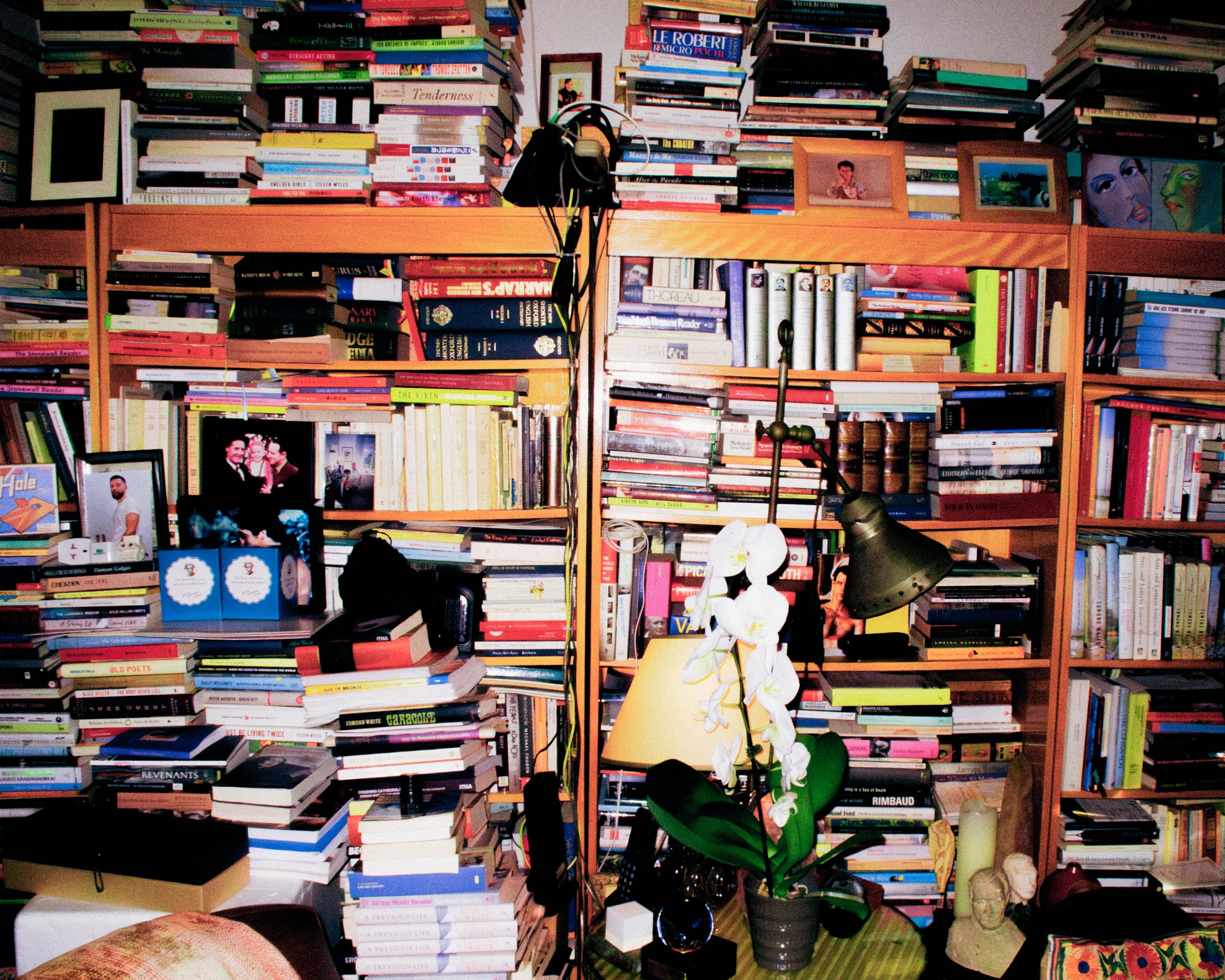

Besides sex, White’s other great subject is art. As an adolescent reading the “gloomy” novels of Thomas Mann, literature was a portal for White into a world of both artifice and romantic longing. Years later, after he became a published writer himself, he seems to have known an entire cultural elite: Susan Sontag, Robert Mapplethorpe, Gore Vidal, Tennessee Williams. Aestheticism and eroticism went hand in hand, and chance encounters often erupted like “spontaneous combustion”, such as his meeting with the English writer Bruce Chatwin. (“We were still standing in the doorway when we started groping each other.”) He tells me there was only one who ‘got away’: Farley Granger, the handsome bisexual star of Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train.

Yet AIDS seemingly wiped out this cultivated world overnight. Has modern gay culture become more dull as a result? “Maybe the average gay person is a little more conformist than they might have been in the past. Conservative people took over the movement. And the whole thing shifted to the right.”

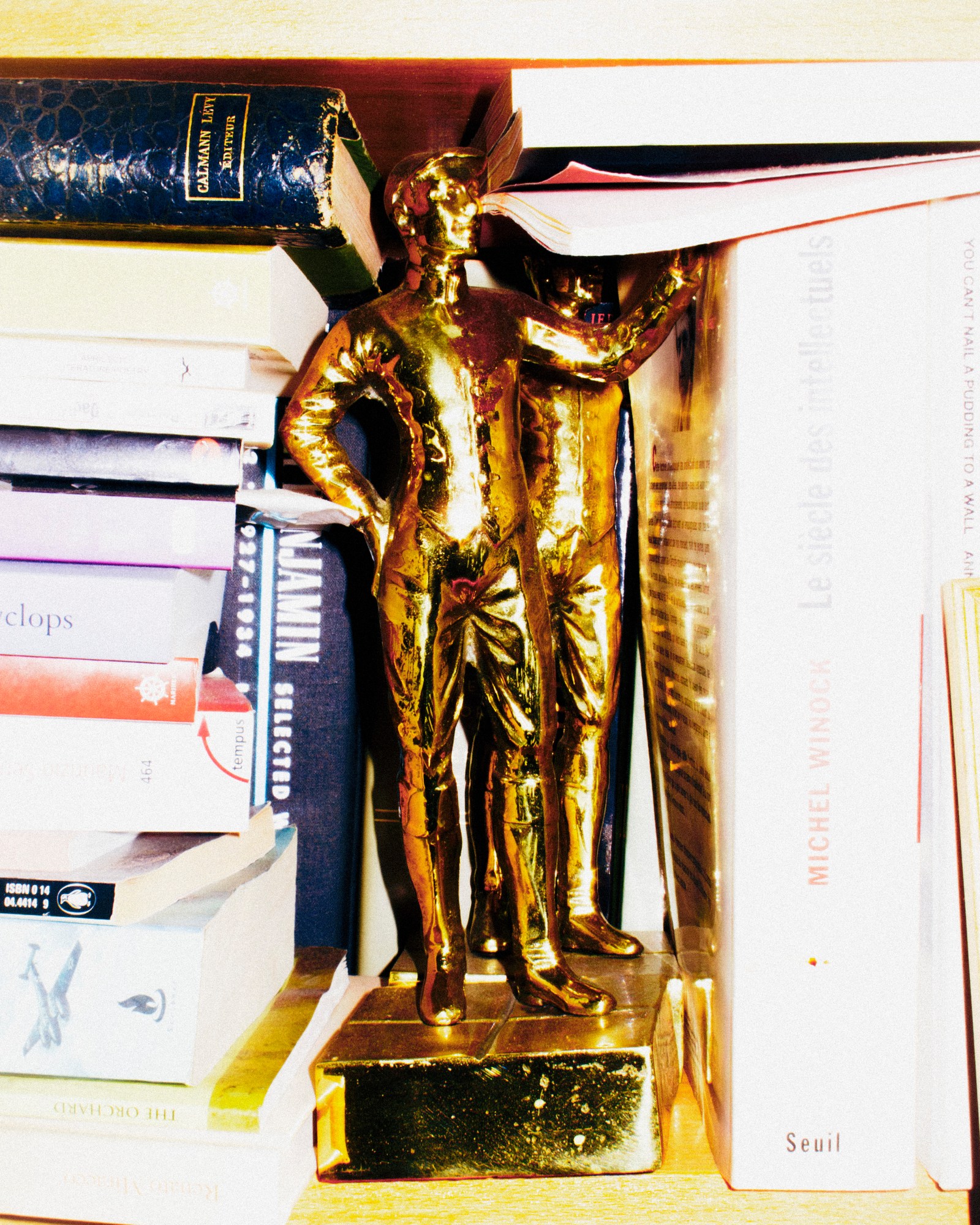

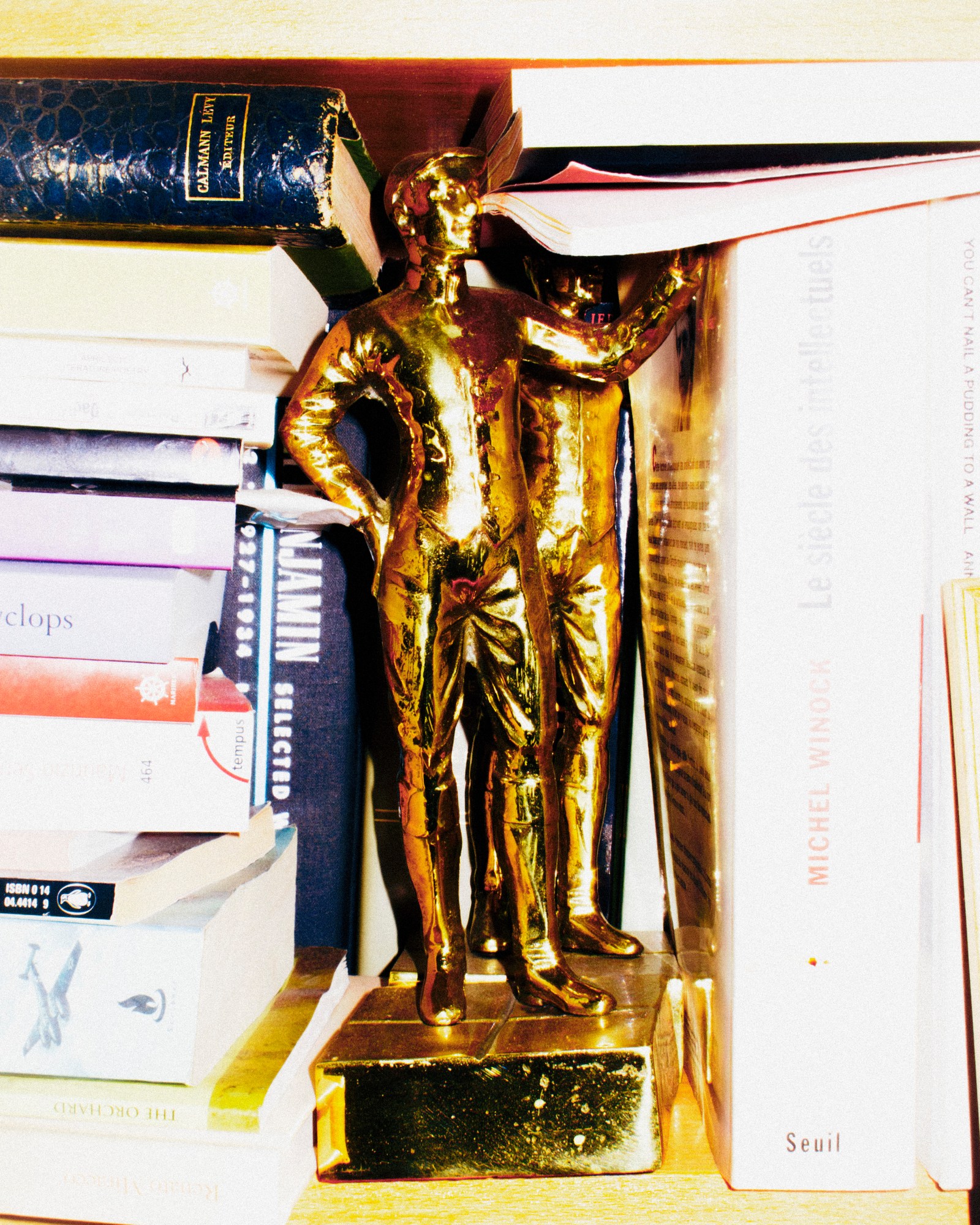

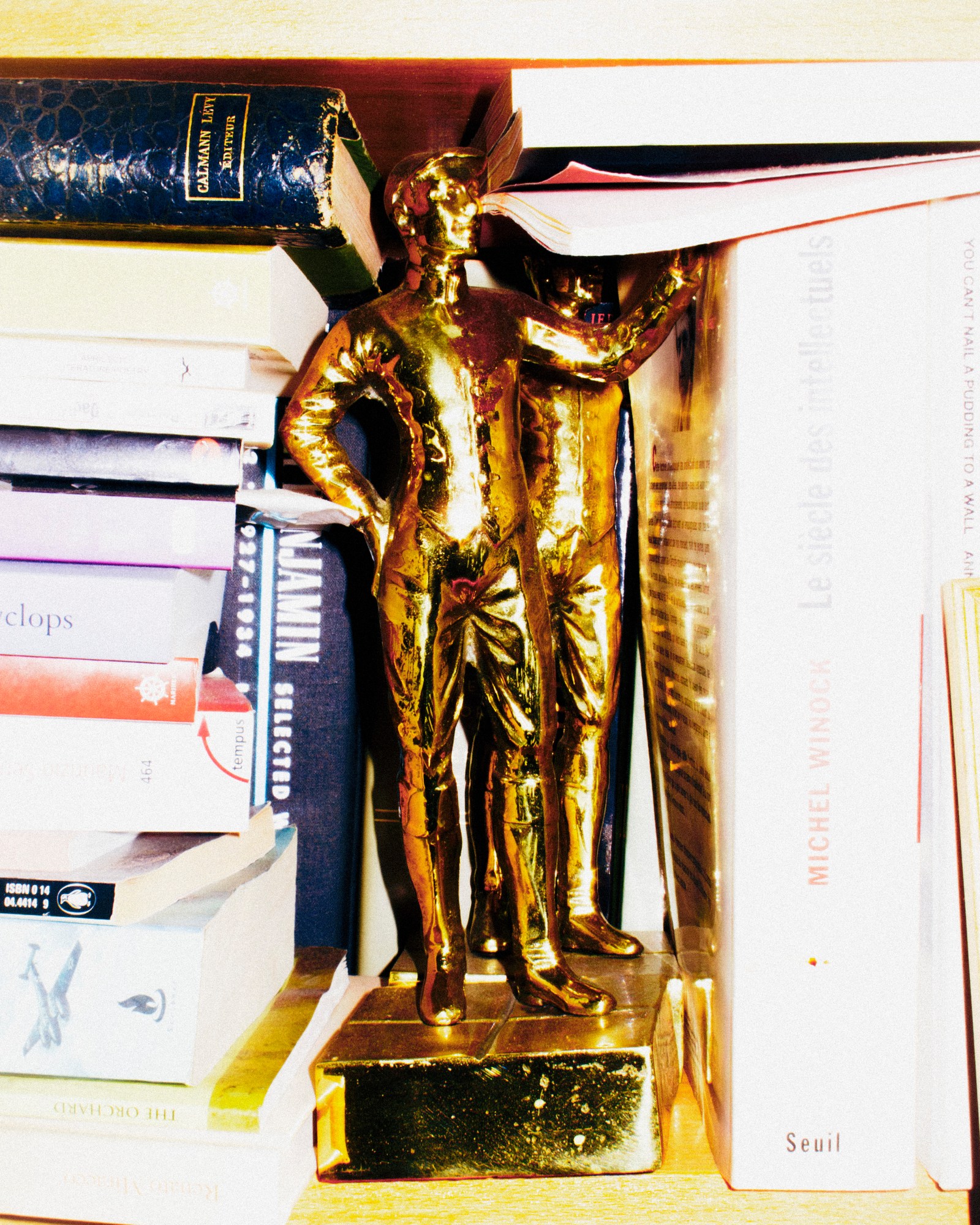

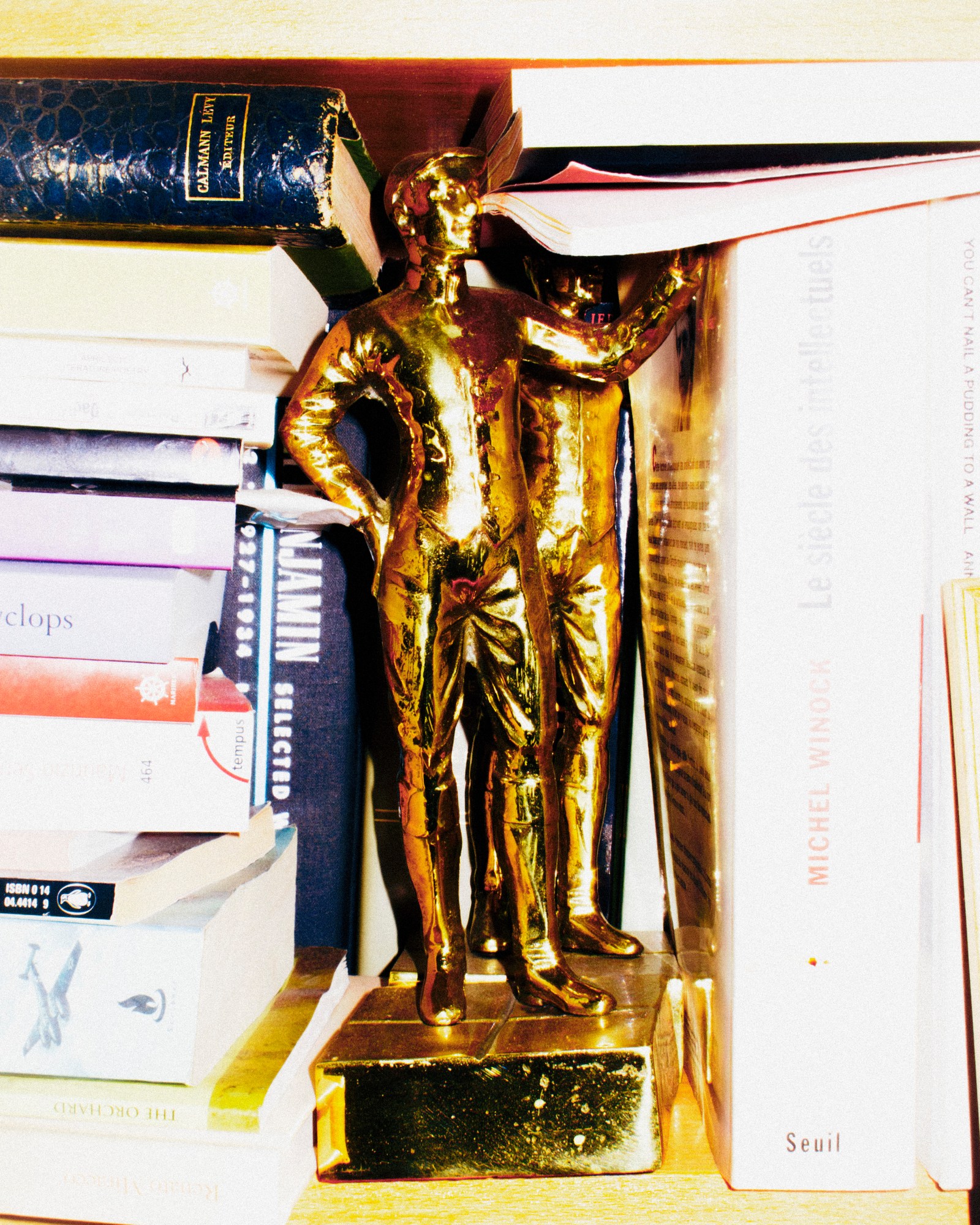

Though his sexual adventures may largely be over (“I’ll never have another lover – / Too much of a bother” he writes in a poem at the end of the book, dedicated to the “Italian stud who broke my heart”), his voracious appetite for reading remains undiminished. He raves about Tom Crewe’s recent The New Life (“it has the steamiest opening you’ve ever read”) and has a book about the eccentric French ‘30s interior designer and art collector, Carlos de Beistegui, on his to-read pile.

Despite finding himself now, as he writes, in the “cold polar heart of old age”, he isn’t nostalgic for the past: “I live very much in the present,” he says. And he acknowledges the chip of ice in the heart of the writer who must value solitude above all else. He quotes his late friend, the composer Virgil Thomson: “Writers have to break up with you sooner or later – that’s what they write about.”

‘The Loves of My Life’ is out now via Bloomsbury

Credits

Words: Daniel Culpan

Photography: Jackson Bowley