“We were screaming and shouting because it was the first time an American, Black, and somebody like me, who was […] controversial too, [was inducted into the Chambre Syndicale du Prêt-à-Porter des Couturiers et des Créateurs de Mode]”, said fashion designer Patrick Kelly in an 1989 interview, discussing his ushering into the highest echelons of fashion design. “Gaultier was just as controversial too, and it was a big honour to be in the realm of Madame Grès, Saint Laurent, Sonia Rykiel, and people like that. I want to have some fun. I don’t think you have to not enjoy life to be successful.”

Along with his predecessors and contemporaries — Arthur McGee, Stephen Burrows and Willi Smith among them — he was part of a generation of Black designers who introduced a never-before-seen energy into the fashion industry. Patrick’s particular contribution was a quirky, surrealist take on design accented by the subversion of racist imagery as an act of Black empowerment and reclamation. He effortlessly balanced social consciousness with luxury business — a feat that only a few have since achieved — and “paved the way for other Black designers, including Kerby Jean-Raymond of Pyer Moss and Telfar Clemens of TELFAR, to engage directly with racial themes,” writes fashion historian Michelle McVicker in the FIT Fashion History Timeline entry on Patrick Kelly. On the ways in which these designers imbued their work with a sense of the complexity and beauty of Blackness, she underscores how Patrick “set a course for many of these contemporary designers to feel emboldened to use the diversity of Black culture in ways to empower audiences […] emphasising the impact of nuances from spirituality and social injustices to celebrating artistic rigour from music to dance.”

Undoubtedly, Patrick’s perspective was rooted in his experience as a Black man from the South. Though much attention is placed on his Paris takeover later down the line, his roots in Vicksburg, Mississippi, offer glimpses into the evolution of his design process and the motifs he deployed throughout his career. The mismatched buttons that served to create his signature clinging, form-fitting silhouettes, for example, hark back to a technique that Ethel Rainey, his grandmother and perennial muse, made her trademark while mending Patrick’s clothes. The home sewing influences of Patrick’s childhood make themselves notably felt in his Fall 1986 collection, where one of the dresses features a heart-shaped button arrangement on the bodice. Indeed, notions of the home and of local community were key pillars of Patrick’s designs — as well as in the work of his peers like Willi Smith. Decades later, designers like Kerby Jean-Raymond and Telfar Clemens continue to weave ideas connected to Black domestic life, especially Black spirituality, into their work. Aspects related to the Black church — such as congregation members’ Sunday best style — deeply inspired Patrick and remain key reference points in the work of contemporary Black designers. Since 2015, for example, a Pyer Moss show mainstay has been the Pyer Moss Tabernacle Drip Choir Drenched in the Blood — a now 90-member choral ensemble formed by Kerby as a homage to the traditional core of the Black church, and a highlight of the brand’s seasonal spectacles. Kerby has also spotlit facets of the Black community beyond the church. Throughout Pyer Moss’ SS19 collection, for example, pieces were printed or embroidered with masterpieces by visual artist Derrick Adams, celebrating the institution of the Black family and depicting Black people living their daily lives in leisurely and bonding activities.

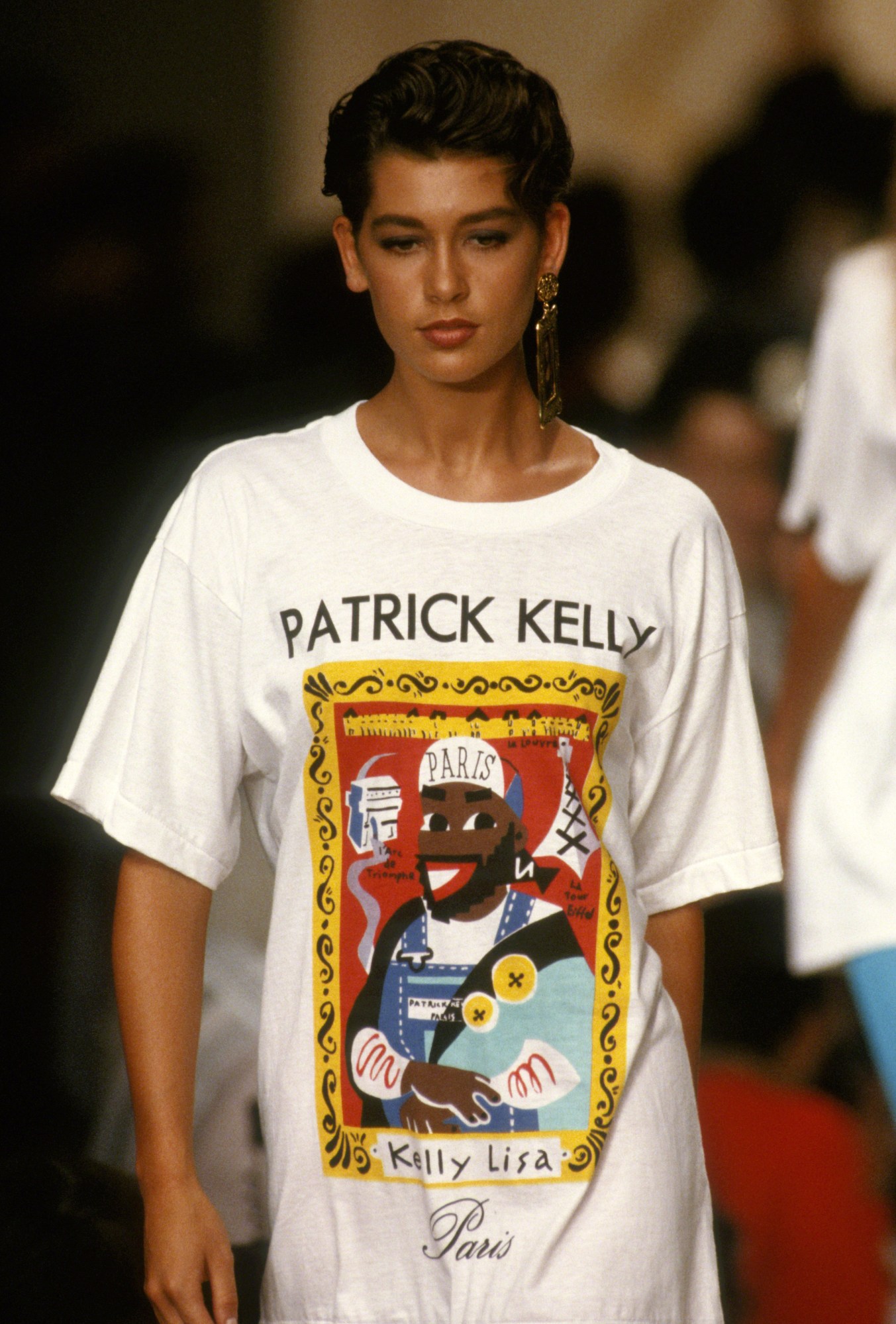

A pervasive aspect of Patrick’s upbringing was the racism he experienced, a feature of his life he saw no reason to omit in his work. At the height of his brand’s success, he used golliwog illustrations in its official marketing campaigns and brand logo. Patrick used the images in such a way that their racist symbolic value was destabilised, recast as a sign for a Black community rapidly accruing power, against and in spite of the constant oppression its members faced. He “believed that these images could be reappropriated in a way that would transform […] the harm implicit in the origin of these images by making something beautiful and asserting that [these images had no] power to shame him or any Black person,” explains Eric Darnell Pritchard, a fashion historian and Patrick Kelly biographer with a forthcoming publication on the designer’s life.

It is, of course, important to remember that Patrick worked at a time when fashion was still very much dominated by Eurocentric ideals, and the industry was, by and large, unwilling to admit to its flaws. Against this background the designer still managed to cut through, his work was well-received in Paris — the city he moved to in 1980 after a short stint at Parsons. “At the beginning of his career, […] the incorporation of racial imagery went without comment from the European fashion houses who gave him any attention, which was little if any,” Eric says, “But as his popularity in Paris grew, and his business began to take off and become more visible to the fashion industry at large — especially the American public back home — the sensitivities some people had to Patrick’s reappropriation of those images became clearer,” he notes. Patrick’s eventual parent company, Warnaco, for example, were allegedly reluctant to distribute the golliwog-branded Patrick Kelly shopping bag for fear of protest. Hesitations quickly subsided, though, with Patrick Kelly Paris (the company he and his life partner Bjorn Amelan founded in 1984) signing a multimillion-dollar deal with the conglomerate backer in 1987, setting a precedent for LVMH’s backing of Rihanna’s FENTY or New Guards Group’s lucrative acquisition of Off-White three decades down the line.

As Patrick’s reputation in Paris rose, his popularity among the Black American media grew, too. “Ebony Magazine did a feature on Patrick looking at his journey to success in Paris and featuring his designs. Jet Magazine regularly covered him, as they did other notable Black designers in America and internationally,” Eric explains. “In sum, there was a tremendous sense of pride in his achievements and, though he was flourishing in Paris, there was great respect and love from Black people in America for his successes.”

Though Patrick may have paved a way that generations of Black American fashion creatives in Paris have gone on to follow, he himself was deeply inspired by someone who made the journey long before him: the iconic Josephine Baker. For his Fall 1986 collection, he even had his friend, model Pat Cleveland, sashay down the runway in a banana-fringed skirt and coil bra top — a nod to the ensemble the late starlet wore in her performances at Les Folies Bergères in the late 1920s. “He made the great escape. Just like Josephine Baker. Oh my God, he was so in love with Josephine Baker. That was sort of our lynchpin and what connected us,” reminisces Pat in an interview with Sessums Magazine, hinting at what made the design so significant: its representation of the immediate community he built around himself and its celebration of the people, things and cultures that laid the foundation for his success.

It’s at least in part why, in the gift bags given to the attendees of his exuberant runway shows, Patrick would include a “Love List” on which items spanning his favourite foods, like fried chicken, and music from hip-hop to gospel were listed. It was Patrick’s way of subtly giving his typically predominantly white audiences a brief education on his design process while simultaneously outlining aspects of various Black experiences in the hope of expanding their purview. “I think it encapsulates joy because it articulates plainly, and repeatedly, things that he loved and felt were important,” reflects Eric in the Dr. Monica Miller and Eric Darnell Pritchard in Conversation about Patrick Kelly programme, part of The Museum at FIT Black Fashion Designer symposium as an extension of the institution’s 2016 exhibition.

Today, contemporary designers throughout the African Diaspora, from London to New York to Johannesburg, are building on the shoulders of Patrick’s career, making their unique experiences of Blackness canvases for their diverse perspectives on beauty. Take Cameroonian couturier Imane Ayissi, for example, who was recently inducted as a guest member of the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture. His work, with its fabrics and silhouettes rooted in Cameroonian textile traditions, acts as a means to dismantle traditional European presuppositions of his craft. Designers like Nigerian-British Duro Olowu or Cameroonian designer Claude Lavie Kameni demonstrate similar boldness in their integration of elements from their West African roots, from indigo-dye processes to wax prints. And in New York, Hood By Air’s Shayne Oliver has brought elements from Black subcultures like Ballroom — and other Black and Latino queer underground scenes — to the runway with joy and panache. Indeed, each of those named, and so many others, are pioneers in their own right. Still, no matter how distinct their aims and practices may be, they all owe a debt to the legacy of unapologetic Black fashion expression created by Patrick Kelly.