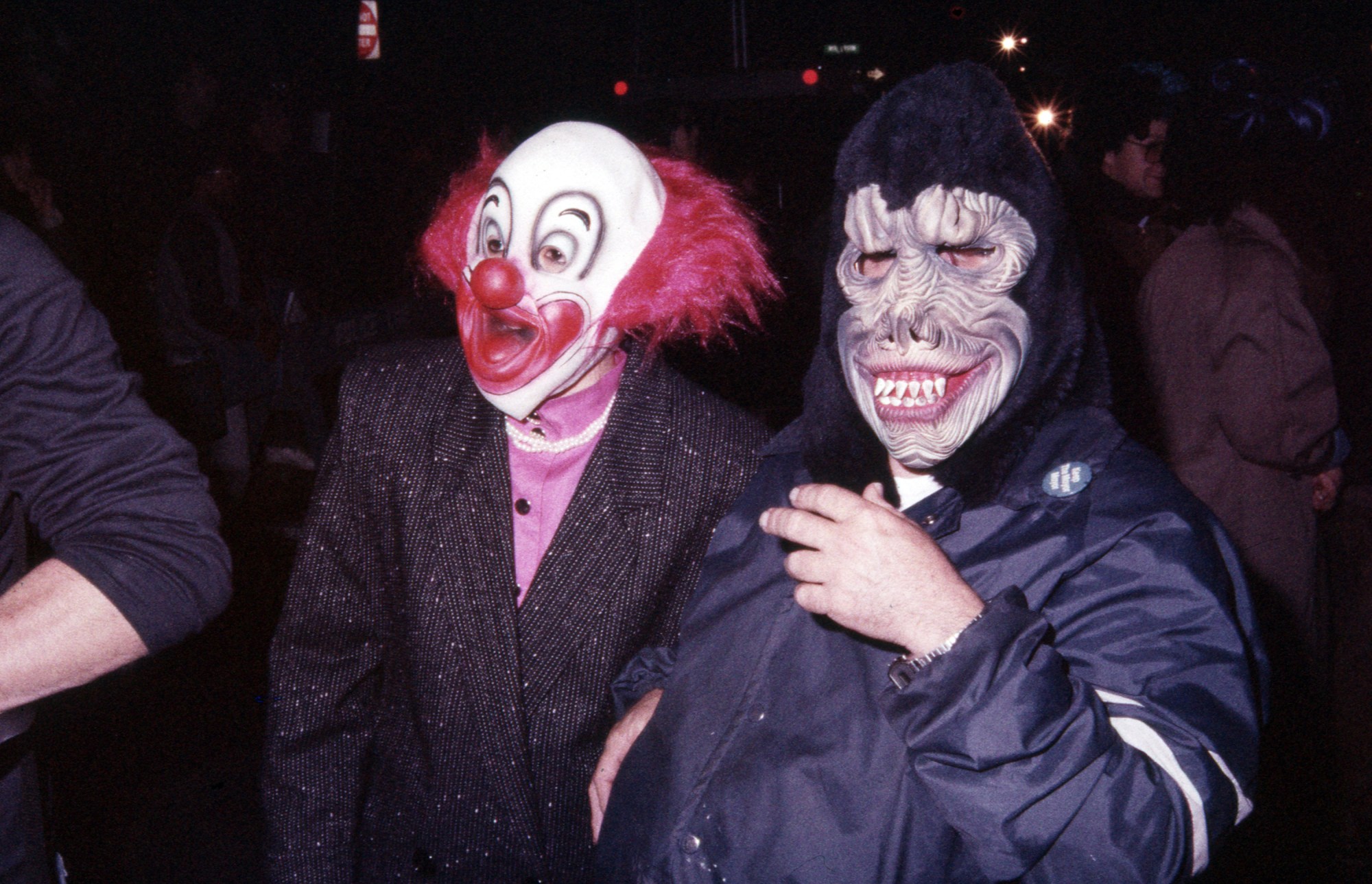

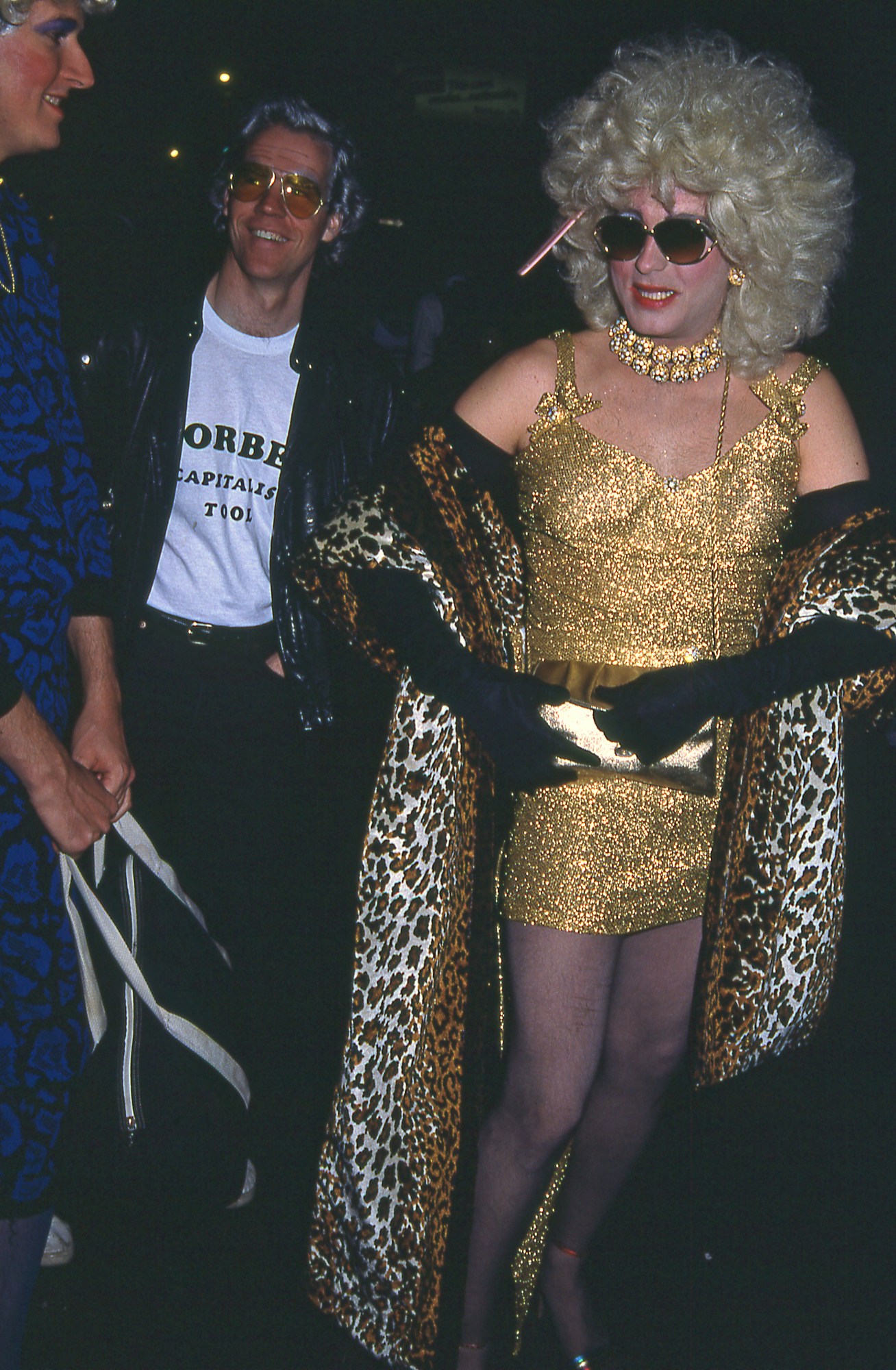

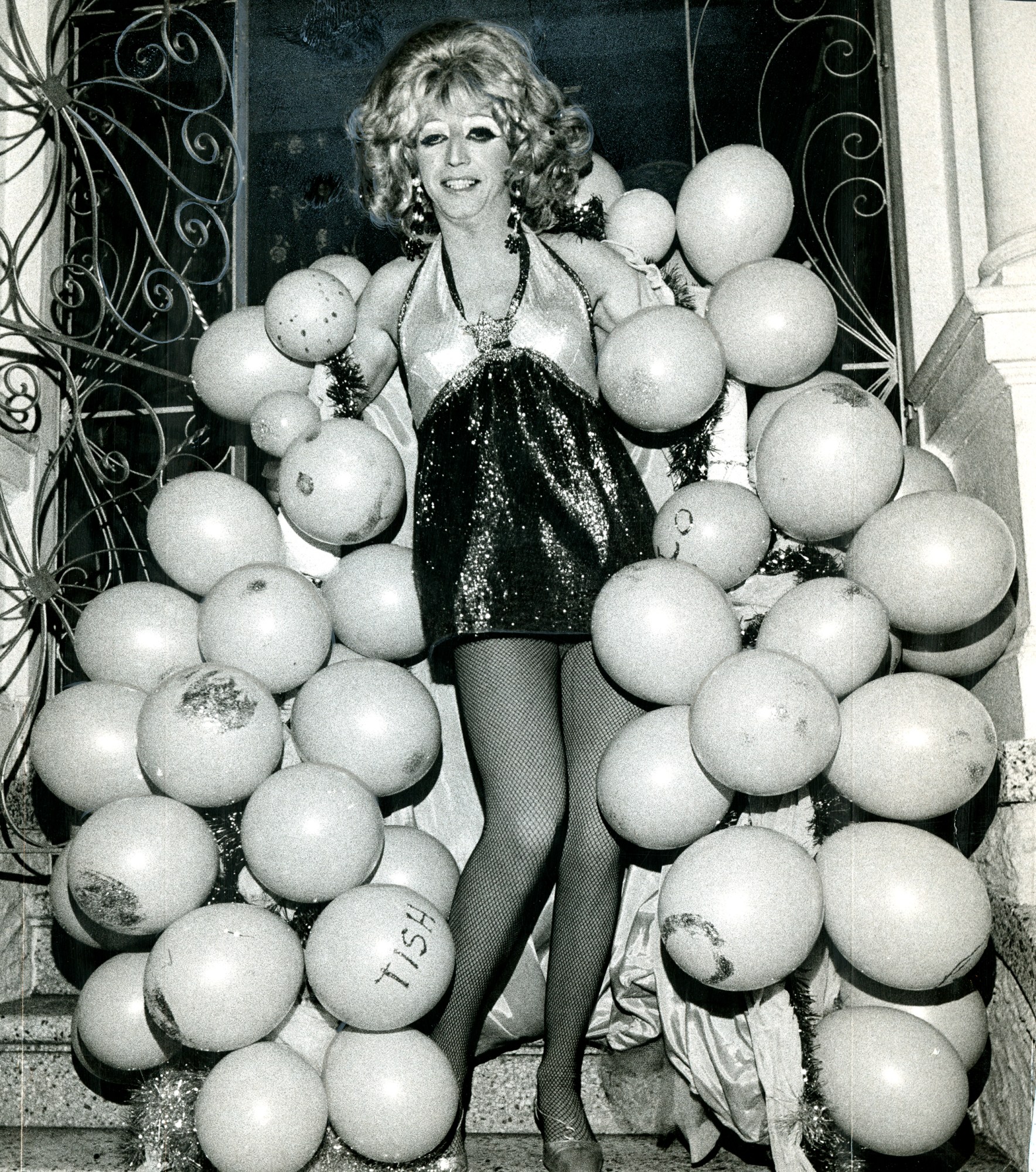

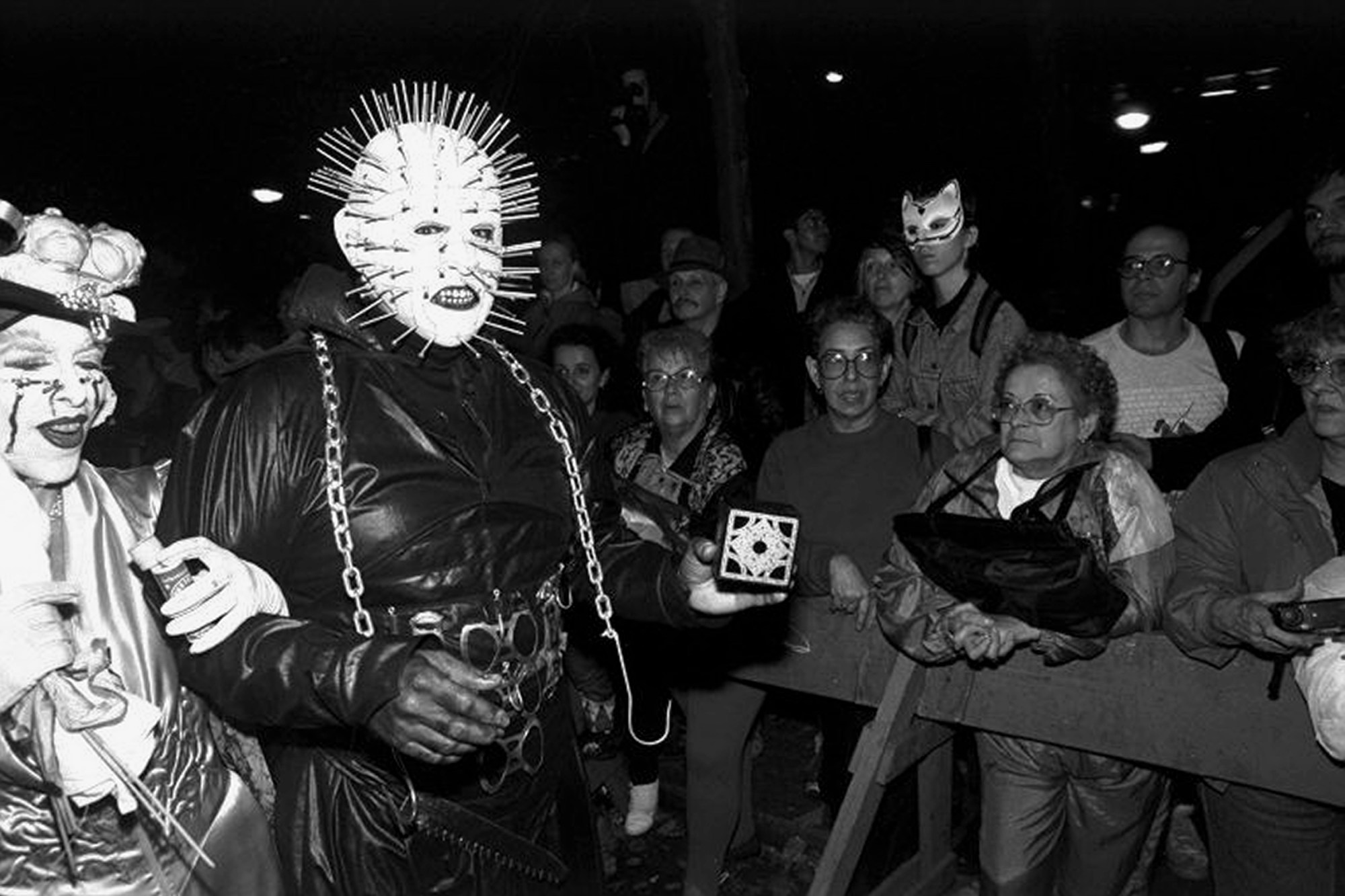

On Halloween night, a bearded man in white robes wore a headdress of animal skulls and flowers, joining a parade of monstrous and spooky puppets. A person in an impish mask dripping in purple glitter led a real horse through it; drag queens in vintage convertibles with the roofs down followed. From fire escapes, queer viewing parties in fabulous fancy dress shouted their support.

These are scenes from the iconic Greenwich Village Halloween Parade from the 70s and 80s – an event that, when it began in 1976, had only 160 people in attendance, comprised mostly of Black trans queer people, drag queens, and other members of the LGBTQ community. Today, it’s become a major event, drawing 2 million people a year.

Queerness is baked into Halloween. At the time of the Greenwich Village Halloween Parade’s inception, it was a day of rebellion and freedom, staged in the wake of the Stonewall protests in 1969. But look further back, into the 40s, and Halloween still had significant queer importance: it was a way to resist draconian laws that made dressing counter to your biological sex illegal and punishable by imprisonment. LGBTQ folks in queer-centric cities like in San Francisco would embrace gender ambiguity and invert ideas around heteronormativity at Halloween parties, risking their freedom – and even their lives – to do so.

“Homosexuality was, throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, understood as unnatural and pathological,” Dr Isabell Dahms, acting conveyor of MA Queer History at Goldsmiths, University of London says. In this context, persecuted queer people were able to use Halloween as a mask of acceptability.

Decades have passed, and with it has come social progress for many (if not all) of those persecuted people. But the framing of Halloween as a holiday inextricable from queerness remains, so much so that it’s often called the ‘gay Christmas’. While the festive season conjures up falsely polite conversations with homophobic family members for many, Halloween lends itself to spending time with friends and chosen family instead. For people who don’t fit into traditional heteronormative roles, Christmas can exhausting at best; at worst, triggering. Halloween, on the other hand, remains a queer playground.

Drag, in particular, has deep connections to Halloween, so much so that many drag artists get their start dressing up then. Arya Quinn, a drag queen and illusion makeup artist, who describes herself as “the shapeshifter queen of [England’s] northeast”, was one of them. “[Halloween] gave me the space I needed to dive into it,” she says. “I was able to go to straight spaces in drag and feel safer. It was easier to blend in.”

This year, like many queens, Arya created 13 looks for her Instagram through October, inspired by horror tropes. She says she’s particularly inspired by characters from Ryan Murphy’s famously camp series American Horror Story. “There are so many different characters, almost anyone can find themselves in it and fit in,” she says of the show and its relationship to queer culture.

Way back to the early days of gothic horror, the genre’s proximity to queerness has been at the forefront. The parallels between classic horror characters and queerness are easy to spot across the board: Mary Shelley was probably bisexual. The original Dracula of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel might have, some hypothesise, been gay. Frankenstein creatures struggle to find their place in a world that fears them (and then there are the mad scientists, driven to realising their own creative visions often at the cost of their own wellbeing). Almost all the creatures of horror find themselves as social outcasts, and as such, the genre can be seen as one that celebrates queerness, while also representing the fears and prejudices society has used to attack the queer community.

Increasingly, these tropes have been reclaimed as the former; a celebration of weirdness, of otherness, of rejecting social norms. The Rocky Horror Picture Show, Young Frankenstein, Fright Night, The Lost Boys, Buffy The Vampire Slayer, The Craft… the list of horror titles that represent and celebrate queerness is almost endless.

The queerness of Halloween lets us break free from the parts of life that hold us back from being true to ourselves, by rejecting what we think we’re supposed to do. Gigi Engle, an ACS certified sex educator at 3Fun and author of All The F*cking Mistakes: a guide to sex, love, and life, used Halloween as a way to discover her own identity and sexuality, in part by rejecting the costumes she felt didn’t speak to her true self, swapping out her conventional ‘hot girl Halloween’ outfit Daphne from Scooby-Doo costume for the show’s lesbian, gawky sidekick, Velma. Now, she sees Halloween as central to the queer community she is a part of. “It’s a chance for the queer community to really bring all of their wonderful sparkly creativity to the forefront and run freely into a holiday that allows us to free our inner child.

“Now,” she says, “when immersed in queerness, we get to celebrate the kids we didn’t get to be.”