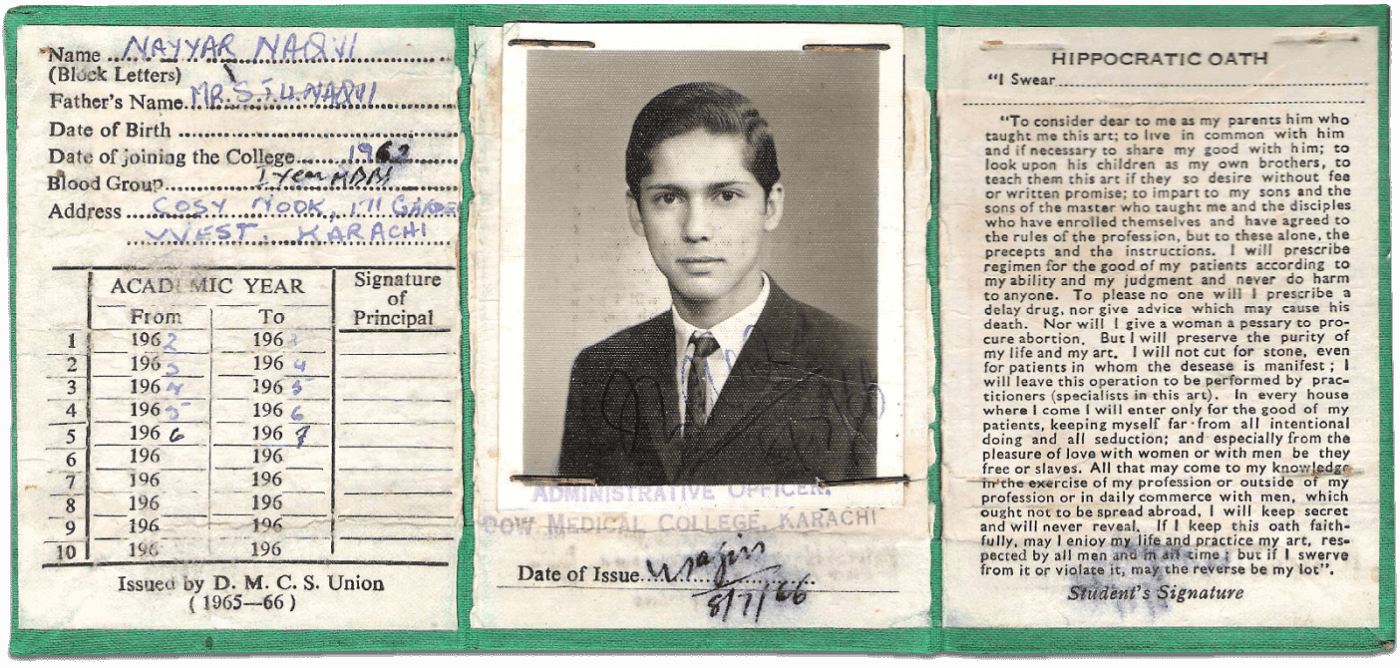

Heart of the Nation: Migration and the Making of the NHS, which opened both digitally and physically at London’s Migration Museum last month, celebrates the vital roles that migrant workers have played in building our health service, through oral histories and emotive, compelling archive and contemporary imagery, as well as art, animation and data visualisations. Allyson Williams is just one of many health professionals – hailing from Iraq, the Philippines, Rwanda, Turkey, the Caribbean and beyond – who has shared her stories with the museum.

“There was a lot of racism from the patients. They would ask if we lived in trees. Were there lots of monkeys? Did we live with them? And this was in 1970.”

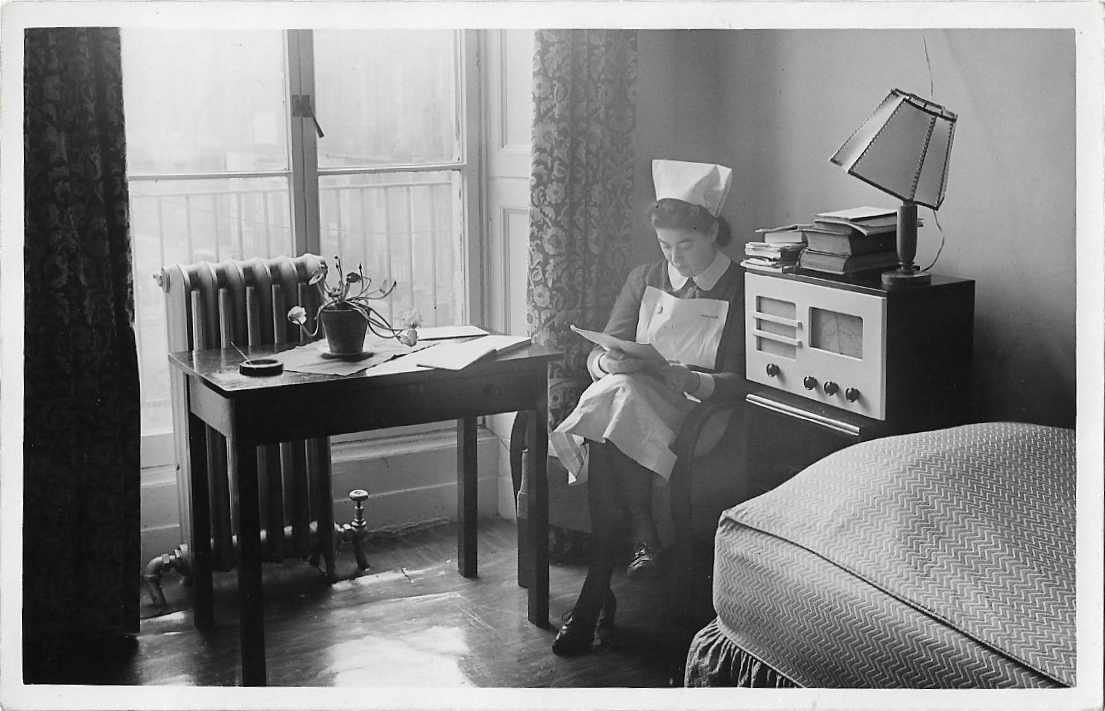

Allyson, who came to from Trinidad to work for the NHS in 1969, is recalling those early days in a north London hospital, and how the reality of Britain stood in stark contrast to the ideal she’d been sold about the ‘Motherland’. “They would slap my hand away because they didn’t want my black to ‘rub off’,” she says.

Decades later, migrant workers in the UK still suffer as a result of racism and xenophobia. Just last year, The Migration Observatory found that 44% of British people want to reduce the number of immigrants coming to Britain (22% of which say ‘reduce a lot’). What this attitude forgets — or neglects to remember — is that the NHS, our best-loved public institution, was built by migrants. From its inception in the late 1940s, NHS recruitment campaigns across the former British empire created a workforce of myriad nationalities and ethnicities. This diversity has endured: today around a quarter of NHS staff are non-British nationals or from a minority ethnic background, rising to around a third of nurses and health visitors and almost half of doctors.

Self-described “NHS veteran” Allyson was taken aback by the Britain she found in 1969. “It didn’t compare at all, it was such a shock,” she remembers, “back home I had a wonderful life. I never thought about race, all just got on and lived together.” Allyson recalls a vibrant Trinidad, picking fresh fruit and vegetables in her family’s garden, a mixed “cosmopolitan” community, neighbourhood parties, space and light. “And then I came to London. I’d never thought about the way people lived here, the houses all stuck together, the smoke coming out of the chimneys, and lots of old derelict buildings. So much ruin. It was quite different to what I’d imagined.”

Brought up in The Commonwealth and taught about ‘Queen and country’, Allyson was surprised to find her intimate knowledge of Britain was not reciprocated by the English. “They had no idea where Trinidad was for a start. They didn’t know what the Caribbean was. I thought, ‘My whole life is based on your life, your system. How come you don’t know anything about me?’ It was very, very sad.”

“I rang my mother and said I wanted to come home, these patients are racist and rude and ungrateful, and I don’t have the chance to work properly because of them. She told me, ‘Absolutely not – you’re there to study, you don’t have to like the place, or the people. Find a way to deal with it. They’re racist: that’s their problem, not yours.’”

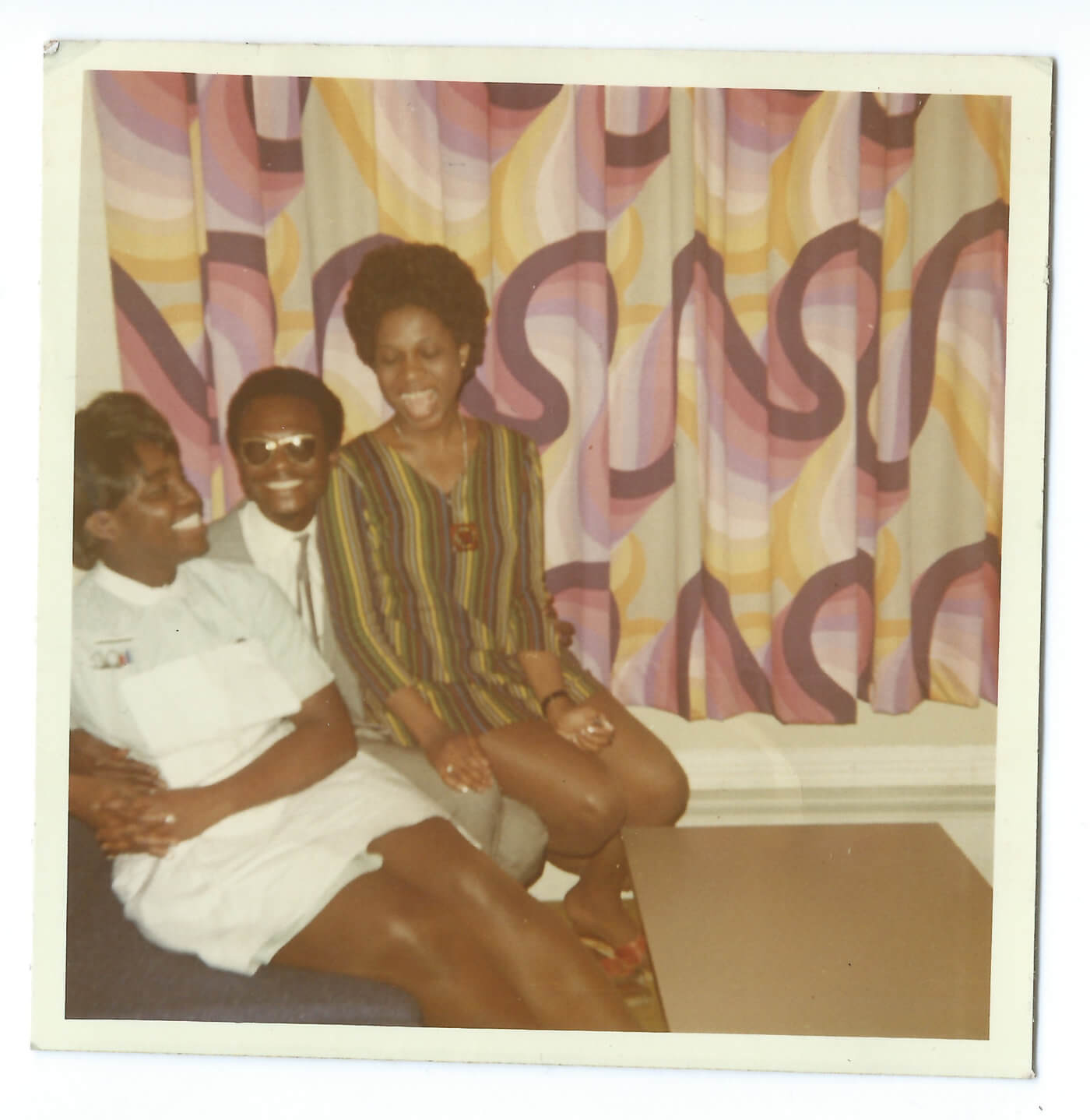

Despite what she suffered at the hands of her patients — the very people she was trying to help — Allyson heeded her mother’s advice, and says she’s glad she decided to stay. She embraced the music culture in late 60s-early 70s London, remembering dancing to R&B and reggae at house parties in Tottenham, Brixton and Croydon, or the Cue Club, Hammersmith Palais and Ronnie Scott’s in Soho. She went on to start a family here, too, and become an integral part of UK culture: her late husband Vernon was one of the founding members of Notting Hill Carnival. The two of them even formed their own Mas band — Genesis — 40 years ago, which she and their daughter still manage at Carnival every year.

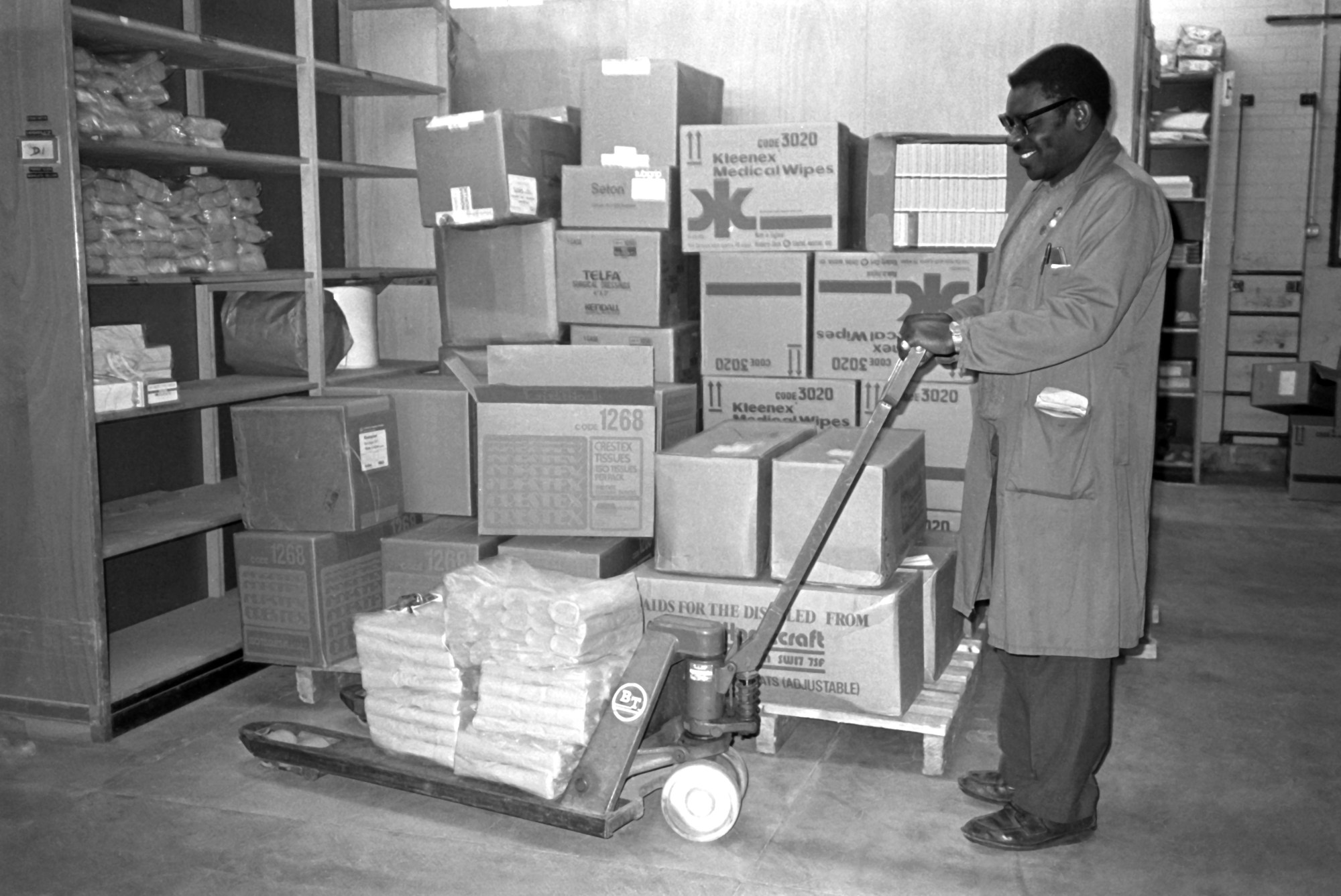

And her career in the NHS ended up bringing her a lot of joy too, as well as recognition. “I always thought it was such a privilege and an honour to bring life into the world,” Allyson says of her specialism, midwifery, recalling how women she’d helped would remember her, some even naming their babies after her. “That has been so lovely.” Allyson eventually rose to become Hospital Services Manager and Deputy Head of Midwifery at University College London Hospital, and was awarded an MBE 18 years ago for her outstanding contribution to the development of midwifery services for women in London. “I was ecstatic,” she says now, of the award. “It was something I never had on my radar — to me, I was just a grassroots midwife, so I never imagined anything like that. I was very grateful and humbled by it.”

But whether it’s awards from the Queen or weekly “claps for the NHS”, there is still a dissonance, lack of acknowledgement, and inherent racism in how many see the health service in this country. “It was frustrating and upsetting that in so many of the adverts and tributes you never ever saw migrant workers or Black faces,” Allyson says. “But sadly it doesn’t surprise me.” She hopes though, the Migration Museum’s new show is a step in the right direction in addressing the problem. “This country is built on migration, to be very honest”

It may not be quite as explicit now, but the under-appreciation Allyson felt in those early days remains, and it has a tangible impact. Failure to properly protect healthcare staff during the pandemic has led to a disproportionate number losing their lives to COVID-19: since the beginning of the pandemic more than 600 health and social care workers have died of the disease in Britain. Meanwhile, the immigration health surcharge (which just increased from £400 to £624 per year) forces migrant staff to pay twice for health care in the UK – once in their visa and again in taxes on their earnings – a kick in the teeth for those risking their lives to care for the health of others.

Another contributor to the Migration Museum exhibition is someone who’s not taken these injustices lying down. Dr Meenal Viz — born in Gibraltar to Indian parents — arrived in the UK to work in the NHS in 2018. This spring, at 27 years old and heavily pregnant with her first baby, she cut a dramatic, striking figure, leading protests at the gates of Downing Street for frontline NHS workers to be provided with proper PPE. While initially reluctant to speak out about the lack of adequate protection for healthcare staff — she was worried her maternity pay might be affected if she spoke up — Meenal was spurred into action by the tragic death of a fellow NHS colleague in April. Heavily pregnant nurse Mary Agyapong died in an intensive care unit at just 28 years old, after becoming infected with the coronavirus while working in Luton and Dunstable Hospital. “That’s when I decided to take my protest to Downing Street,” Meenal says. “To remind all the politicians about the rights of our healthcare workers.”

Unlike Allyson, Meenal’s early experiences of being a migrant NHS worker weren’t full of overt racism, but instead she experienced first hand the quieter, more covert inequalities embedded in British society; the public performances of support and love for our health system that aren’t backed up by actual policy. “I was quite naive to the realities of our government and the system we live in,” she says. “But now I’ve noticed it more, I’ve realised the more subtle discrepancies and subtle forms of discrimination. Our ministers and government are indifferent to suffering. They’re indifferent to the realities of what we [NHS staff] face on a daily basis. I have to hold my patients’ hands and tell them that they’re going to die.”

Meenal says that while the claps and official acknowledgements (in the recent Queen’s Birthday Honours Lists health and social care workers make up 14% of those receiving BEMs, MBEs and OBEs, with 41 nurses and midwives compared to 17 in the last New Year Honours List) don’t make up for discrimination or underfunding, it’s a step in the right direction. “To see women of my background and my colour receiving honour from the Queen really brings me a lot of hope,” Meenal says. “They’re blazing the trail for people like myself and those who have the same skin colour as me. It’ll never make up for the decades of racism our communities have faced, but it’s a positive step in the right direction that has to start somewhere.”

Exhibitions like Heart of the Nation, celebrating the contribution of migrants like Meenal and Allyson, are a part of that too: “They are needed,” says Meenal. “If it wasn’t for them, the whole backbone of the NHS would completely crumble.

“I hope people understand how important diversity is — the world cannot run on just one group of people, it can’t function if it’s just one community running everything,” she adds. “The world would be quite boring if we were bordered up in our own countries. The beauty of the world is that we all bring our own experiences into the pot. That’s what shapes and creates community, society, businesses, and things like the NHS. We can all come together as a global community and help each other. There’s a beauty to that.”

The Migration Museum is closed to the public for at least four weeks from 5 November 2020, in line with the new government restrictions in response to Covid-19. They hope to welcome visitors back safely soon.