Remember when your most recent phone pics were from nights out instead of saved memes about 2020 being the worst year ever? A blurry toilet mirror selfie with people you’ve just met. Friends dressed up, dancing and drunk. Strobe lights reflecting on a mirror ball. “The Time We Call Our Own”, a newly opened show at Liverpool’s Open Eye Gallery curated by Central Saint Martins MA Fashion Image leader, and co-founder of the Preston is my Paris zine, Adam Murray, celebrates those nightlife moments in all their glory. Exploring time, place and identity, it reminds us of the diversity and joy of nightlife across the globe, from Lithuania to Latin America.

Even before the pandemic, nightlife venues were under threat. Clubs will likely be the last places to reopen and it’s uncertain whether the industry will fully recover. That’s why exhibitions like this are so important. They remind us that nightlife isn’t just frivolous hedonism but the lifeblood of culture and community. Spaces like pubs, bars and clubs are vital for social and mental health as well as for the economy.

We spoke to Adam about curating the exhibition, the cultural fascination with documenting nights out and why he believes these spaces are vital institutions and that they are considered as such as cities reopen.

How would you introduce the exhibition?

Nightlife is a core theme but what’s more important is how photography can engage with shared identity through place and interests. Obviously music is a big part of that — the role photography has in documenting and communicating, as well as the role that these nightlife spaces have in a city. A lot’s changed since coronavirus in terms of the importance of social groups and face to face interactions. It’s not just about nightlife.

The show is taking place during a period of cultural nostalgia for going out. How do you think that influences the way the show is received?

Before lockdown, nightlife was something that was such a big part of our lives and something we expected to always be there. Of course now we realise how important it really is. People who have the power to allow these spaces to exist or not will hopefully realise their significance and importance.

How did you go about selecting who to include in the show and which cities and cultures were going to be represented?

The subject itself was moving on from the “North” exhibition and this idea of how people engage with photography. One of the main ways that most people have engaged with photography is through documenting their experiences with their friends and social groups. Even iPhones are sold on the fact that they can take photos at night time and you’re gonna get these amazing pictures of your friends. That type of photography hasn’t really been dealt with in terms of an exhibition. It’s often seen as quite frivolous and not a serious topic, but it is a subject that has many entry points for people. People can relate to it. That’s one of the things we learnt from “North”, that you can encourage people to engage with the work as something that relates to them and doesn’t feel too distant.

Oliver’s project, Andrew’s and Miriam’s have existed as photo books from as early as 2012. I’ve spent a long time with the work and really enjoy it, but it was also important to make sure each project was offering something different in ways that the photographer was engaging with the work. In some cases the photographers were much part of those groups, and they were very much insiders. In some cases, Miriam’s for example, the technology isn’t necessarily the most advanced or expensive. She just spends a long, long time in these spaces and builds up a mass of digital images. There’s a film in the show that is just filmed either on a small digital camera or a phone. You don’t necessarily have to have access to huge amounts of high-end equipment to make a really engaging project.

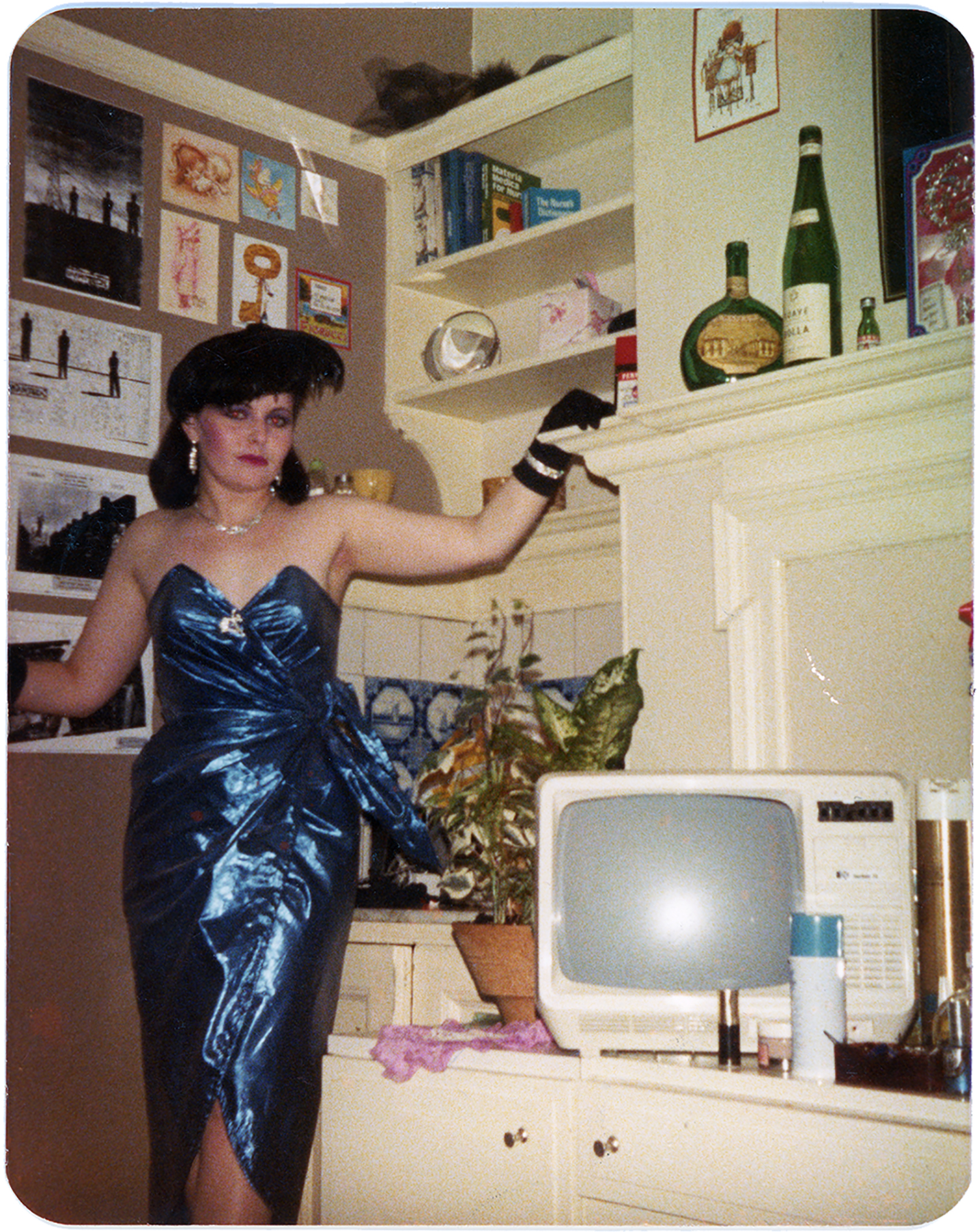

A lot of the show talks about visibility and using photography to show these different groups and what role that has in terms of visibility and awareness. With Amelia’s project it was only ever intended as this very personal archive just for her and her boyfriend at the time in the late 70s and 80s. Each project does something different in terms of how photography’s used and also something different in terms of who the people are and what photography is doing by working with them.

Why do you think that the need and desire to document nightlife has endured across cultures and time?

As an activity, it’s something that most people really enjoy. It’s something that everyone can relate to. I think it’s a vital part of social life and the world. In terms of photography, it gives you a view into something that you kind of knew existed, but you wouldn’t necessarily know where these spaces are or wouldn’t necessarily go to these spaces yourself. In general, it’s a very seductive kind of subject. It’s not just a case of photographing people having a nice time. It covers a lot to do with relationships, the roles of space, dress, identity, performance.

It’s been noted that paying rent to live in a city in lockdown felt pointless because the cultural perks of being in a city including its nightlife were inaccessible. How do you think nightlife changes the mood of a city?

I moved to London the week before lockdown, so I’ve experienced that directly. All we’ve been talking about is how there’s almost no point living here for the last six months. You almost accept that it’s going to be hugely expensive because of all the add-ons and benefits of being in the space. All those add-ons haven’t been here. It’s really made you question if it’s worth it. I think that is one of the challenges for cities coming out of this. They’ve got to think, “Why are people here?” Hopefully, now that things are starting to reopen, people will realise how important these spaces are for people. That becomes a bigger part of the conversation. Most of the coverage of any sort of night spaces has been about them closing down or licensing. What’s nice about these projects is that they show that these are vital social institutions and that’s existed for years. Not just in big cities, but in small towns. The role of pubs and social clubs are also vital.

What do you hope that people come away from the exhibition thinking and feeling?

If they go and see it in the next couple of weeks, they might feel this longing to be in a similar kind of space again so it might be a melancholy feeling coming out of it. That’s one of the great things that photography can achieve. I hope they also recognise the value of their own archives more. In the past, there have generally been one or two photographers who have documented subcultures or youth movements or specific nights. They’re the go-to people and they have the power to decide who out of that group is important and then editors would decide which social group or which night is significant whereas these days everybody’s documenting everything they go to and who’s to say who or what’s more important?

“The Time We Call Our Own” is generously supported by SEVENSTORE. Exhibition runs from September 3 to October 23.