The month of June officially marks Pride in many countries around the world. Since 2003, Istanbul Pride has taken place in Taksim Square, where participants gather to march down İstiklal Avenue, and where over 100,000 people turned up in 2014 — making it the largest ever LGBTQ+ celebration in Muslim-majority country. The following year, however, queer people and their allies were met with police wielding water cannons and rubber bullets and the government has banned Pride ever since. People still gather each year, but face increasing hostility from the conservative Turkish government.

Homosexuality isn’t illegal in Turkey, but discrimination runs rampant and attacks on LGBTQ+ folks are on the rise. The sociopolitical climate has forced queer people to fend for themselves, creating their own venues, galleries and safe spaces to build community. Though artists, especially, struggle to make a living as a result of censorship and homophobia, amongst the underground scene there’s love, solidarity and resilience in the face of all the hate.

We spoke to ten queer Turkish artists about their stories, their struggles and their hopes for the future.

Beste Ileri, multimedia artist

“I have a desire to show how I was broken and my artistic practice is mainly based on that. I like to reflect the dark and twisted ways of life, existence and nature. I have a background in contemporary art, but I work in all sorts of mediums. Recently, digital art, painting and installation. Through combining archival and fictional works, I try to discuss gentrification, environmental control, borders and ecological issues with both documentation and performative works. I also deal with ‘home’ in terms of the queer settlement, appointed/elected family, organization, women’s status and domestic demographics.

Being queer is a political statement, but it becomes even more political when you’re living in Turkey. Last year, some of my friends got arrested and have been targeted by the government for being LGBTQ+ and making queer art. Now we’re working as a collective and keep making our off-the-beaten-path art, doing even more widely acclaimed exhibitions and protesting.

I dream of queer liberation in Turkey for all industries and social contexts. I want for all who are ashamed of their way of existence or need to fight to gain recognition, to be brave and not afraid to be different. While expecting to be understood and accepted, we shouldn’t forget to try to understand and accept others as well. Be tolerant, receptive and questioning. Even if things seem really dark at times, being productive and expressive is really crucial. That is the thing that will heal us.”

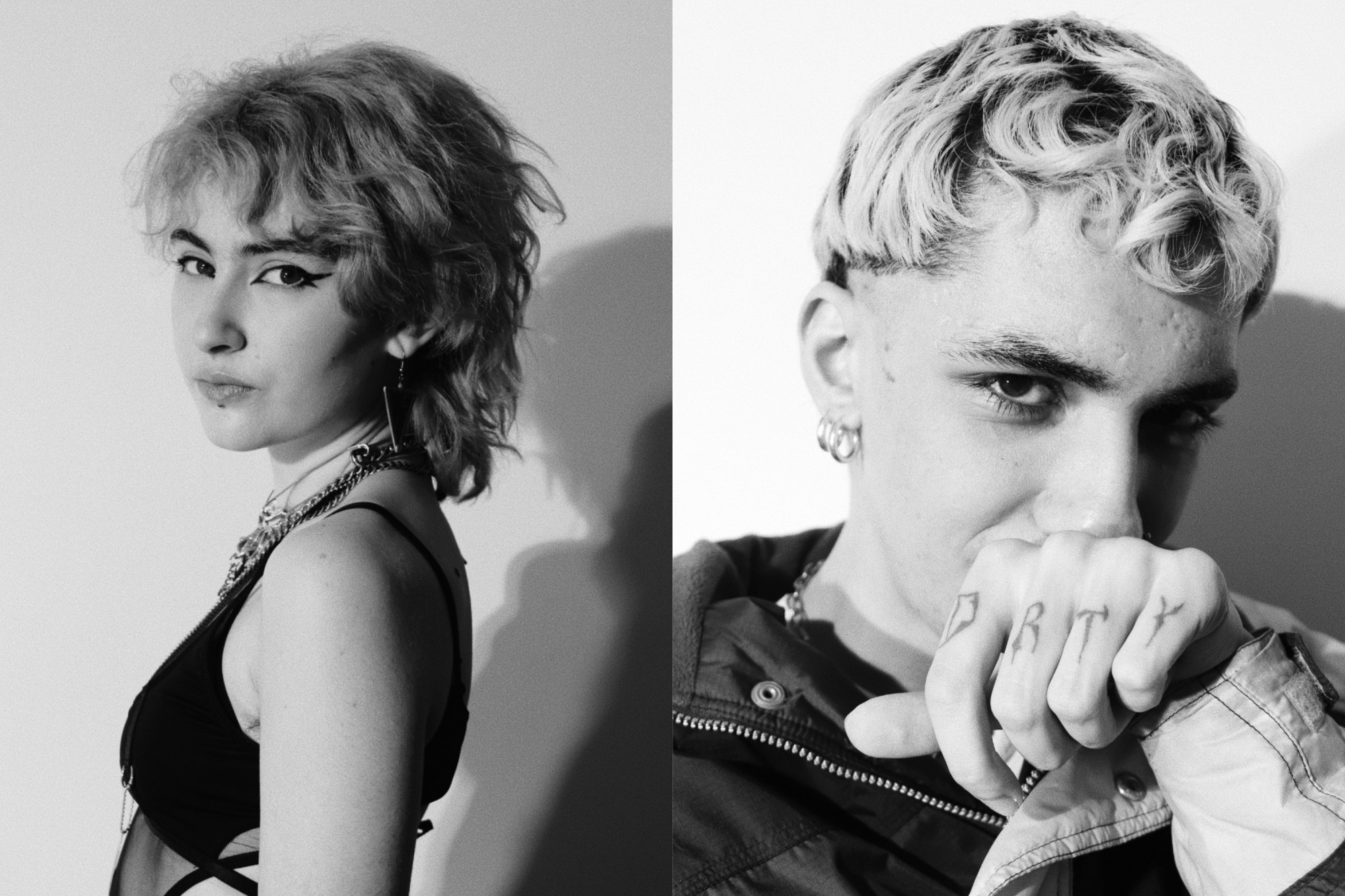

Antre, photographer/art director

“I was a little goth kid in middle school. I felt as if that was my community as we were different. But as people like to call goths sad, we were anything but our music taste. We were really happy kids. It was more about feeling strange and unable to fit in, but there was a beauty in that strangeness. My identity crisis as a teenager influenced my work and who I am today. Darkness influences my work, the power to open your heart to darkness and live through this world fearlessly.

There are struggles for queer artists everywhere. It’s hard to walk around Istanbul without understanding that there is risk. But this community proves that with a sense of togetherness, with trust and love and that sense of family there is a way to make it. I hope that the sense of unnecessary hatred is eradicated one day, that there are no restrictions on art. We are so excluded. We have our own queer art fairs, which are incredible, but it’s extremely limiting as we don’t get to sell our garments and art freely amongst other people. The differentiation is always lingering there. Making art isn’t cheap anymore, and artists need to sustain themselves. There are not enough spaces. There are so many new queer artists emerging and because there’s no representation for them, they end up in dark places.

It’s not always bad. But June comes, Pride month is here and the city is engulfed in a cluster of policemen. Walking down those streets, the feeling of that adrenaline of being with hundreds of people you don’t know but you trust is priceless. I’ve been to Berlin Pride and prides in other countries; you see people in dog masks and people kissing each other freely, dressed however they want, acting however they please. I just can’t help but think about what it’s like back home in Istanbul, where people want to shoot us, want to beat us for loving who we love. Every move we take is a protest, everything we do in this lifetime in this country is a revolutionary stance.”

Ceren, videographer

“I was born in Istanbul as the second child of a working class family. I spent my high school years in the suburban neighborhoods with industrial areas, political organizations, the working class and ‘others’ surrounding me. The distorted structure of the suburb left a big impression on me. I am still in an internal war with them. The best part of being in the suburbs, in those years, was going down to the city center. I was excited by the diversity of people and cultures I saw there. Later, I got accepted into an art school in Izmir and started to study cinema. With the freedom of being alone, I went on many adventures and met the underground. When the pandemic started, I came back to Istanbul and started living here again. One day I bought an analog video camera from the flea market. I started to shoot and edit everything I see around me. These moments I captured turned into a documentary of the city and queer life.

It is very difficult not only to be a queer artist, but a queer individual in Turkey. It is an underdeveloped society. Here, even a trans person walking out on the street can turn into a micro-resistance. The current government dominates all the mainstream media, and from there, either massive censorship or hate speech is propagated regarding LGBTQ+ people. It’s difficult to see any fictional or real queer representation in Turkish television and mainstream media. Even though social media has entered our lives, the impact of television is huge, people shape their lives and values according to the constructs on TV. As queerness is continually censored, discounted and targeted in the mainstream; they are neglected, hated and killed on the streets as well. Many people I shoot do not want to be visible because they are afraid that their lives may be in danger.

My dream is to have queer representation in Turkish mainstream media. My biggest dream is to see an ever-expanding queer archive of our own cinematic history. I want to contribute to the social resistance through my personal struggle for existence. I wish patience and fortitude to future generations in their struggle to hold on to their own truths when they are seduced by unoriginal thoughts.”

Dirty Projector, photographer/videographer

“I was born in Istanbul into a very homophobic family. When I started coming to terms with my sexuality and identity, I had a sense that I needed to become financially independent. I started a job as a chef’s assistant at 14, and left it when I was 17. It was an extremely toxic environment, but I did gain my independence through it.

When the pandemic hit, a lot of queer artists and performers were unable to make their means, which resulted in them having to do video performances on the internet. That’s when I bought my first camera with the money I earned and had a newfound love for visual arts and photography. I met Syntia, we started working closely together through Istanbul’s queer community. I then met Antre, and started assisting them at shoots.

I like creating things that I don’t have to explain to people. I take self-portraits and manipulate them, toying around with the topic of my identity in my art. I make myself unrecognizable, foggy, clown-like and almost invisible. It’s how I see myself and it leaves people curious as to how I see them too. I’d like to go back to my younger self and tell them that money isn’t everything. My hopes are to see my community and chosen family grow and prosper, all together.”

JTAMUL, DJ/musician

“I was living in a small town in northeast Turkey and came to Istanbul for university. I wanted to create something that resonated with the culture I was in, so I started making music. I sent a few demos to a label in the UK, called Objects Ltd. and released two EP’s with them. My first one being about local Queer linguistics and slang. I was studying and was incredibly impressed by Lubunca (a local queer dialect — a secret used by sex workers and LGBTQ+), and I wanted to integrate it with my music. That was my debut, and I then started DJing. We are very limited with venues. Especially for underground artists. Post-pandemic, almost every venue has become gentrified and commercial, so it’s tough.

Our obstacles are often bigger than us. My journey has and still is fun and colorful, and my pride lies in being a part of this. I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else, you just have to trust your gut a lot more than you think.”

KIKI ggNASH, Painter/artist/drag performer

“I’m Kiki ggNash and I’m the nightmare you don’t want to wake up from. I am a painter, a performer, a monster transvestite and a social saboteur. As a trans person who is in social transition, I face a challenge in every step I take. It ranges from daily life to the stage.

There was no leading trans figure in painting/performance in the past, so I find myself in that position. Consequently, this puts pressure on me. We live with a population of people who do not understand or value our existence and products, but rather humiliate them and downgrade them.

I live in survival mode all the time. I can become distanced from experiencing life. This can make me forget that I am human. I wish I could find plenty of estrogen. I want to over-bulk on the world like a type of black magic. I dream of shaking and terrorizing the hetero, masculine, skinny and hypocritical art community with my weight. I’m happy to stay here and contribute with my art, but I want to leave this country. Live the American dream and open a studio in New York.”

Mina Lal Kocasoy, visual artist

“I find it hard to be genuine, not just in my art but in daily social interactions. I feel like I constantly have to switch personalities. I was depressed for a long time during my formative years, but I’ve grown and healed a lot. Growing up and finding my people in the queer community, in the punk scene, in the underground art world has helped me get in touch with my true self. Things that used to be rejected by my peers are now celebrated. I wasn’t the one who had to change, the world had to change. It’s a constant battle, still.

I’m an organizing member of Gayya Kolektif, an underground platform for art and music where we lift up marginalized creatives and form spaces for them to thrive. Yet I also work at a high-end art gallery serving some of the richest people in Turkey. It’s difficult to find a balance in such dissonance. I see my parents quite often, but it’s not possible to form a meaningful dialogue if I can’t talk to them about the majority of things I value. I want to be genuine in all my relationships, my endeavors, my art. I want to be myself, not only in underground spaces but everywhere. I want to be an openly queer artist full time, not just when it’s safe to be.”

SIBEL ggNash, designer

“I’d like to say that my story is that of a witch who was born in the 90s in a land where her existence was seen as “cursed”, and she tries to overcome this curse with art. I am sacrificing myself to keep witches like me alive with honor.

My struggle is being myself and I’d like to live and express my feelings freely without hiding them. My wish is to exist with individuality and to transform this individual movement into a social movement. I’d like to tell young artists and queer individuals out there that they are never alone or wrong. And to listen to Kylie Minogue more.”

Syntia, visual artist/drag artist

“I was born in Sakarya, a small city which was quite conservative. My family really loved me and cared for me, but I was so different from my peers that I sometimes felt like they didn’t know how to raise me. I moved to Istanbul to study and because I needed a fresh slate.

I drew a lot as a child, and then music came into the question. Listening to music began to shape me. I was fascinated by Sevdaliza as a teenager. When I look at it now I think it was a way that I could express my queerness because it was rebellious and strange and out of the odds. FKA twigs and Arca completely changed my perspective, helping me understand and question what art and identity really were.

Art feels like magic to me. I want to have a connection with someone even when they look at my paintings or drag performances. I want them to feel me. I want to communicate with people. Not relating to anything growing up drove me to make things that not only were for me but for other people. I dealt with abuse, so I was always making my own safe zones to escape from that even if I couldn’t physically. I have my chosen family now, where we all support and understand each other and overcome our traumas and heal together.”

Tusidi, makeup and drag artist

“I got into drag right before the pandemic, just before I could get my foot on the stage. Then the pandemic happened and I started rehearsing at home, experimenting with makeup. The drag scene in Istanbul is incredibly diverse — you’ll never see two people in the same look.

Before drag, I was always close to my drag family and my drag mother Ceytengri who kept me company on stage on my first performance. I started doing makeup and after seven years in school and only a short time of being in the queer community, I felt as if I had so many capabilities. This push led me to work as a makeup artist and explore my skills and identity, and then I started having fun with nails which became another creative outlet. My inspirations can range from pop culture to sci-fi to horror to cartoons to sea creatures to plants to anything and everything, I try not to put myself in a box.

I want to do a bit of everything. I want to get the recognition and income I deserve, not only for me but also for everyone in my community. Pay your fucking artists. Everything looks good when you have fun.”

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more culture.

Credits

Photography Klara Gordon.

Creative direction/lighting Betül Kaynar