There’s a wall in Ian Lewandowski’s studio on the southside of Brooklyn’s Prospect Park that’s coated in pictures, postcards and memorabilia – each collected with magpie-like zeal. Right now, it features an unfinished sketch of a sailor from a show his friend put on at The Drawing Center, a photograph of someone stretching his covid mask almost to a breaking point, and pages from an old calendar about hairdressers he found on eBay. But it’s an image from an Instagram account sharing photographs of an iconic gay club on Fire Island that was partially burnt down which inspired his new book, The Ice Palace Is Gone. “A lot of the things I was thinking about around that time were to do with safety,” the photographer says. This idea that certain spaces can make you feel validated, while also being “very susceptible to being destroyed.”

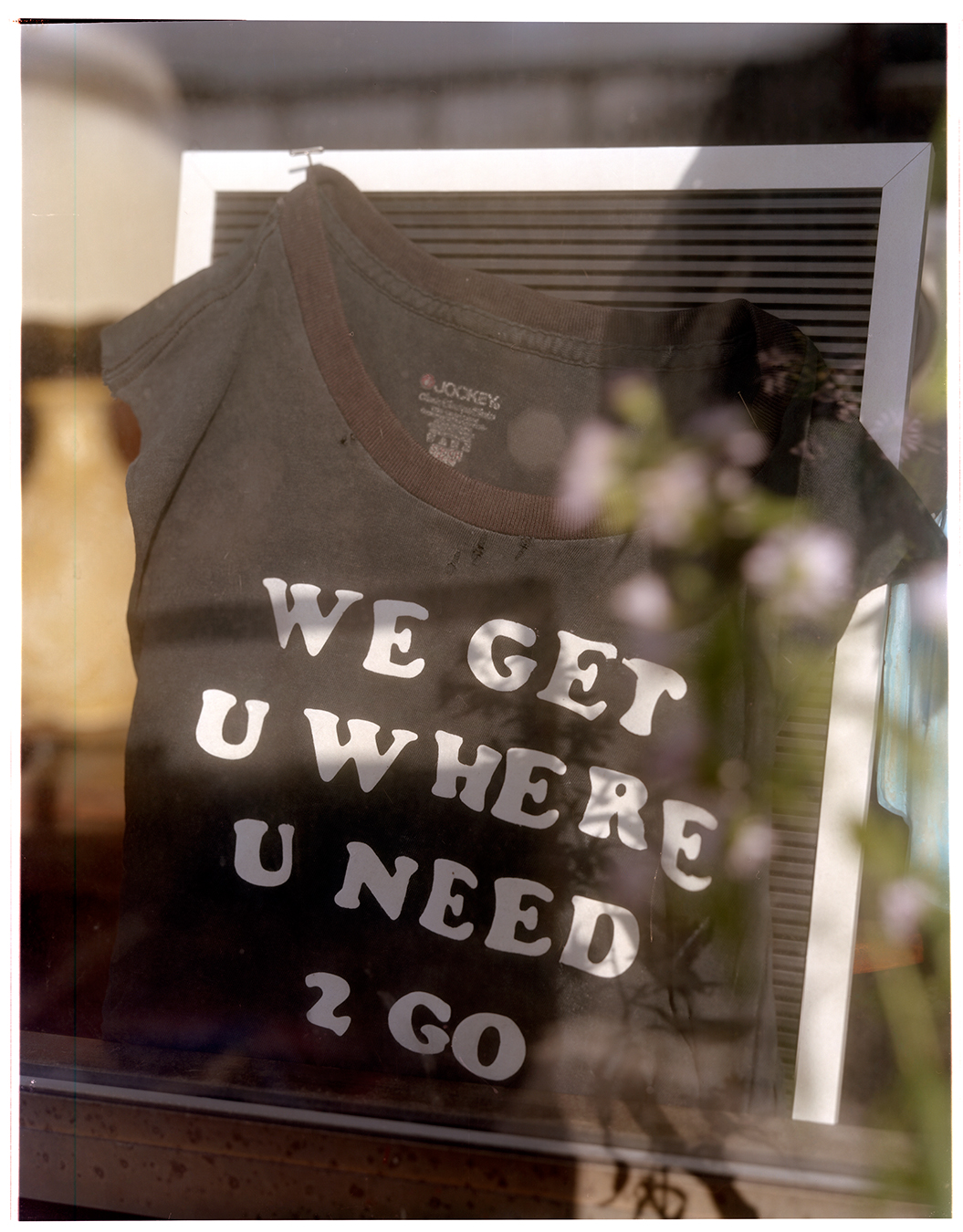

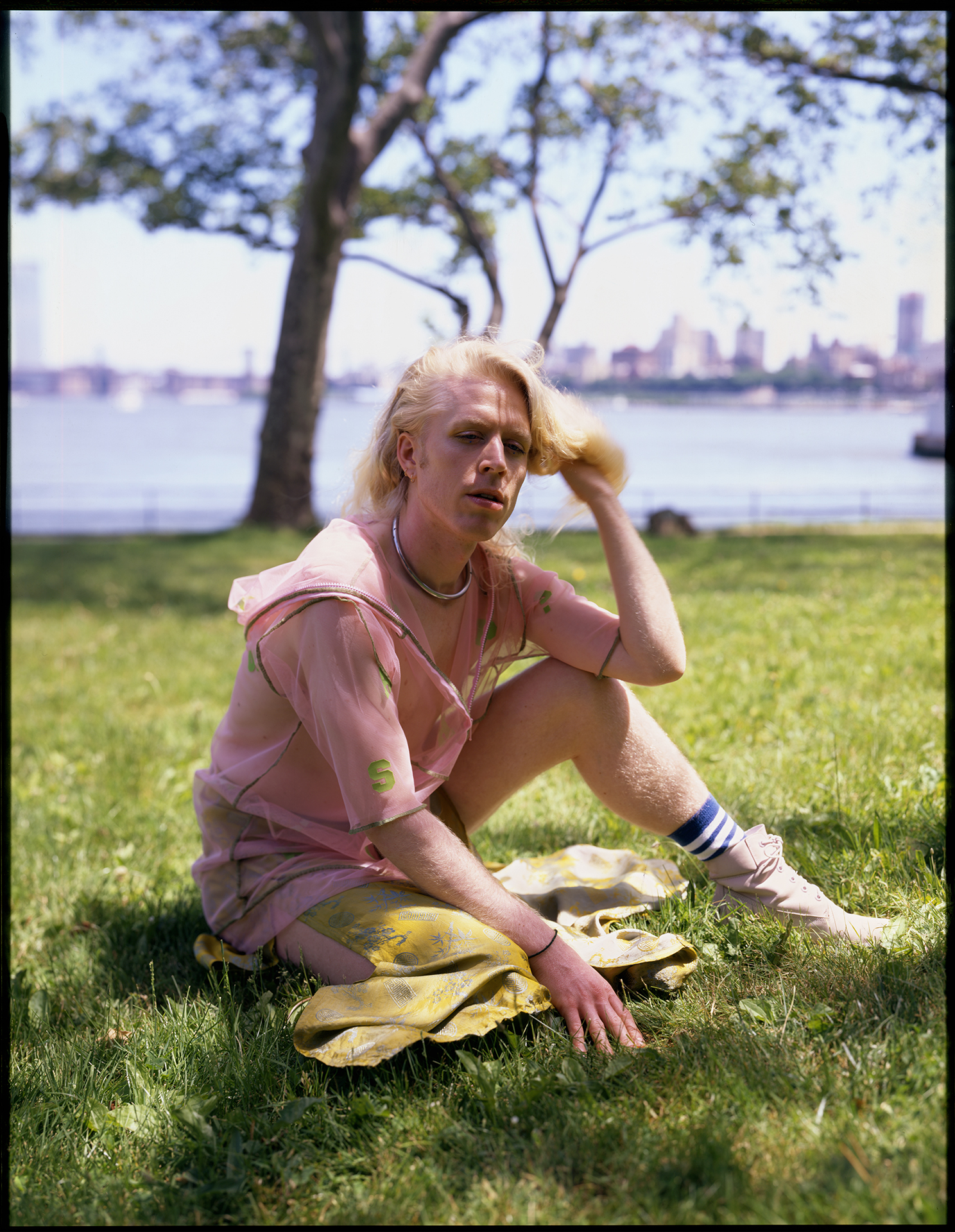

In 2018, Ian began photographing friends and acquaintances in the places they felt safe — bedrooms and studios, partner’s homes and dining rooms — in clothes and uniforms that empowered them. He used a slow-functioning 19th century camera that takes a long time to focus, and that prompted his subjects to think carefully about their positioning, sit with their thoughts and be present. “I think you do lose that fluidity that some people look for in photographs, or naturalness,” he says.

“There’s something interesting to me about how limiting [the camera] is,” Ian says. “I think there’s something almost liberating about having that limit. I can strive to make anything that I possibly can with it, even if it’s hard.” Growing up in a working class environment in Indiana, where labour was fetishized and calls for greater productivity came at the cost of workers, Ian says he internalised the belief that you should push your body to its limits. “I know it’s very harmful,” he says. “But I also think it’s sort of part of me in that way.”

But, unlike his conservative Catholic upbringing, “where we didn’t talk about anything or address any personal issues” and where being gay was not accepted, Ian’s images are all about openness, trust and support. “I’m thinking a lot about permission,” he explains, which wouldn’t exist without the generosity of his subjects with their time. “The permission to engage with someone on that close of a level, or that kind of intimate level. I think my upbringing was… the opposite of that.”

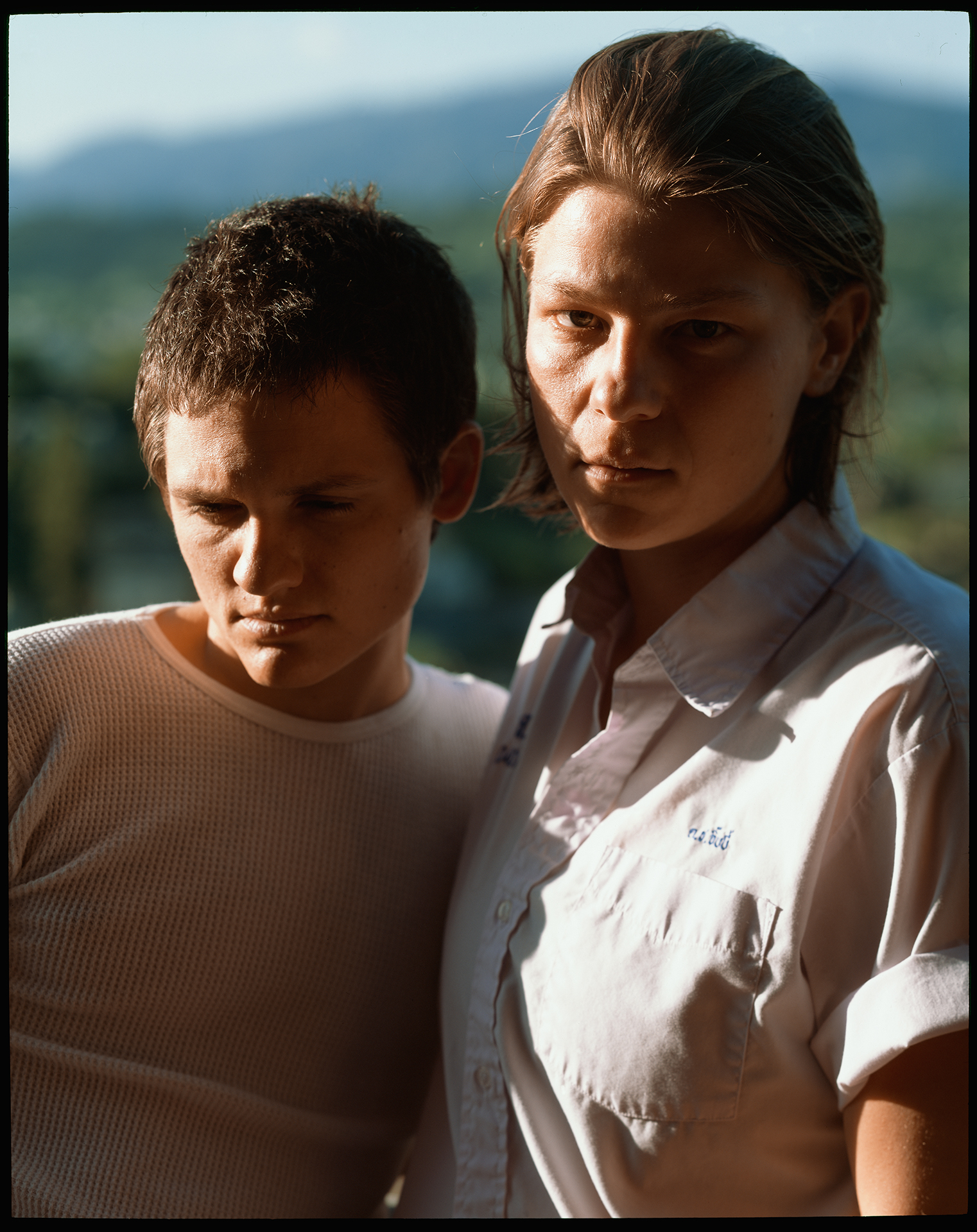

The Ice Palace Is Gone opens with a man in scrubs extending their hand and inviting the reader in. Those in the field of care play a large role in Ian’s work, as hospitals were a dominant feature of his life in 2015 and 2016 while he was treated for lymphoma. Like the photo book’s leading figure, most of his subjects look into the camera with intensity — sometimes seductive, confronting, or at ease — but always creating a connection between subject and the viewer. They encapsulate the active persona of someone who has power within the world.

There’s also a timelessness to the images — it’s almost difficult to determine what era they were taken. “In my opinion there are two kinds of image, the disposable and the lasting,” writes the book’s editor at Magic Hour Press. “A disposable image is one of clear intent that is meant to be physically discarded or mentally forgotten once that intent has been achieved. A lasting image is one without such singular intent. It is not pornography meant to arouse (though it could). It is not instructional nor documentary (though it could instruct and it could document, at least as much as a novel does). More than anything, the lasting image finds a way back into your mind.”

It’s how the images work with one another that Ian is most excited by — what is told through a selection of disparate portraits compiled together. “Mostly everything is a portrait… it feels very intact in that way, or sort of cohesive,” he says. “But there are these different methods or different sensibilities going on.” The images capture the very normal lives of the queer community in New York — a woman and her children, performers, artists and couples. That said, Ian doesn’t “presume to give an accurate account” of his artists’ community. “I don’t feel like I’m at liberty to do that, because I don’t think that the medium I use is exactly faithful to real life.”

Ian took an overwhelming number of portraits, over several years, for this project, but only 50 odd made it into the book. Each one tells a story of intimacy, love, self-assurance and pride, never the story of those feelings. “My expectation of the camera is not to give anything that is totally accurate or factual, it’s more I think the camera is really good at describing.”

The Ice Palace is Gone is available for purchase here.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more queer film content.

Credits

Photography Ian Lewandowski