K.O. Nnamdie’s career began earlier than most, at the tender age of 13. Inspired by his older sister’s aspirations to become a model, he turned to the camera, soon booking work as a wunderkind photographer for fashion and culture publications. “Working in image-making for 10 years, I’m used to hiding behind the lens — being that character,” he shared over Zoom on a recent late-summer morning.

His arrival in New York at the age of 21 marked a turning point. K.O. slowly began shifting from his photography practice and position behind the scenes, moving into the foreground as an emerging voice in the art community. In 2017, five years after his arrival in the city, in 2017 he launched Restaurant Projects, a curatorial practice and research-based art advisory driven by an inclusive, community-rooted, abolitionist approach focused on what he calls hospitality.

“The idea of being in service is super important to me, very much engrained,” he says, explaining how his love of food and the environments in which we break bread became a foundational signature of Restaurant Projects exhibitions — most shows culminate in a home-cooked meal. It’s an approach he adopted from his mother, who ran two restaurants in South Miami.

After being appointed Director of anonymous Gallery at the beginning of this year, he’s been bringing this unique logic to new, more traditionally institutional corners of the industry. Standout shows at anonymous, like The Ecology of Visibility and Vegyn, set his name abuzz as one of the most fascinating curatorial voices in the downtown art world. The Last Day of Disco, on view earlier this year at Fragment Gallery, saw him contribute his own durational performance piece.

Reflecting on the development of his latest group show, currently on view through October 29th, he opts for a food metaphor. “base note has been marinating in the fridge for quite some time. It just made sense, to take it out and to start prepping. Turn on the stove, and get ready to start plating this food,” he says.. Nnamdie’s mind has always focused on making a generous offering, as an ode towards his relationship to home. Early memories from growing up in a Nigerian household between Houston and Miami formed the connective tissue for base note, which he explains was inspired by childhood fascinations with scent and music.“Fragrance and music have been very important for me throughout my entire life, growing up around so many beautiful women, around so much music and Black joy, fragrances of food, fragrances of from bottles, music just emanating from all the speakers in the house.”

We spoke more about his creative journey, Aretha Franklin, and what to expect from base note.

I want to ask how you found yourself in the art world, and more specifically, how you found yourself in the position of curator. What has that journey been like?

I grew up with four older sisters. I’m the only boy in the family, and the last child. My youngest sister, Amy, she’s a model and works in computer forensics. My creativity kind of came from being inspired by my sister — she wanted to be a model. So I was gonna be the photographer. Just kind of this really beautiful sibling rivalry thing, at the beginning. I was wanting to try to one-up her as young kids or siblings do.

I ended up finding my true voice, and it started through image-making. That lasted for 10 years. I wanted to take a break from my practice as an artist, and was kind of bored with just that limited mode. I kind of thought, well, what is my community getting into? What about you guys? What are y’all up to? What are they engaged in? What’s the vibe?

So in 2017 I decided to quit a job I was working, at this gallery called Participant Inc. I thought, you know what? I’m actually going to focus on showing my friends. I got into it, honestly, in a very organic way. I did not plan to be a curator. I did not plan to be a director. I did plan to support voices and people within my community and outside of my community. I did intend to encourage communication and also just encourage people’s vision.

That is the real work. That’s the work that my father taught me, when he put ten non-relatives through college. That’s just what people of color do, we show up for each other.

Tell us more about Restaurant Projects.

Restaurant Projects started in 2017. My interest was really to be as hospitable as I possibly could with engaging the public regarding the arts, art exhibitions, and programming. I just wanted to make sure that people of — honestly, any color — but mainly people of my color and people of maybe not the same academic background as most people from the art world, could feel comfortable in this space. I was also, and still am, very interested in food. I wanted to demystify the performance that is the gallery dinner.

I would erect exhibitions and then following the opening, I would close the doors, and whoever was inside would now be treated to a special dinner. It slowly became research material for me. Most people let their guard down when they are putting food in their mouth.

And what about your role as Director at anonymous Gallery, and how it connects to, or is distinct from your work with Restaurant Projects? How do you see those two things?

I absolutely love working at anonymous. The founder and owner Joseph is a dear friend of mine. And he was one of the first supporters of Restaurant Projects, and was very curious and interested in what it was doing. Joseph and I actually got in touch with one another regarding the arts more directly through abolition. I was working with young abolitionists at City Hall, and we needed a space to prepare food for houseless and financially insecure individuals. We made 80-100 to-go meals every night. And to my surprise — not my surprise for him as Joseph, but to my surprise as a gallery — he was very open to it. I thought I was gonna have to fight to get someone to be open to it. I was really grateful for that. I have not actually been this supported before in a workplace environment. It’s really great to know that I can share my point of view and really be heard.

Do you feel you are filling an unmet need in the art world?

What I’m doing is not particularly special. I’d rather just be focused on being in the now garden — what does the community need now, given all the shit that we’ve gone through over the years? I’m not primarily at service to institutions or the private collectors. I’m at service to the artists and the general public.

You’ve mentioned that in this upcoming show, you’re finally saying and expressing things that you didn’t feel comfortable sharing before. I’m wondering — what do you feel has changed to make that feel possible?

This change, this feeling, I’m just now realizing it’s been upon me. It has been around since the first show I did at anonymous, The Ecology of Visibility. When I did that exhibition, it was really just pure. I wasn’t trying to check off all the boxes with that show, but I did. After Visibility, I did a show called Vegyn, which was my interest about algorithms, and how we perform through them. I really hadn’t realized that these exhibitions that I was mounting were also about me until a really insightful curator and friend Serubiri Moses told me, “You know, the shows that you are doing is your work. You put these exhibitions together as if they are artworks.” I have never felt so exposed or seen.

My practice is not simply only coming from an academic place, it’s not just coming from a white place, it’s not just coming from a European place. I am aware of the spaces I am telling stories from. To be able to tell and share these stories with a childlike joy, I must oscillate between different head spaces, but I also go to a place of uncertainty… I go to unknown places.

Can you tell me more about “The Executioner”, a performance piece put on at anonymous as part of Vegyn, in collaboration with Dan Colen?

“The Executioner” was composed of five performers who were reenacting their death on loop. I really wanted to call to the importance of how even after death, the algorithm and the internet still will not allow a soul to rest, or to gain peace.

We are very happy for Breonna’s [justice in court], but she still needs peace! I was thinking about her, George Floyd and so many others that have not been able to get news coverage. So many people outside of the States, in Africa, India, are all going through these traumatic moments. And some of these last moments of living are on TikTok.

I really wanted to show how uncomfortably jarring the algorithm can be. So this performance was lengthy and the sound piece by Brian DeGraw (of Gang Gang Dance) and Dan Colen was Aretha Franklin spelling out “R-e-s-p-e-c-t,” but the sound was also intentionally made to sound like a bullet piercing into the skin. The coldness and hotness of this violence through one’s body is felt in “R-E-S-P-E-C-T, S-P-E-C-T-R-E” (2021).

I like for things to oscillate between different spheres. One aspect of the performance highlights the importance of respecting someone, respecting something. Here is a Black woman shouting pleading with us. Why don’t we listen to that woman? Why don’t we listen to women in general? I was thinking about my sisters and I took on some of that rage.

Tell us about your process of choosing the artists that you chose to work with, and what folks can expect to see at base note?

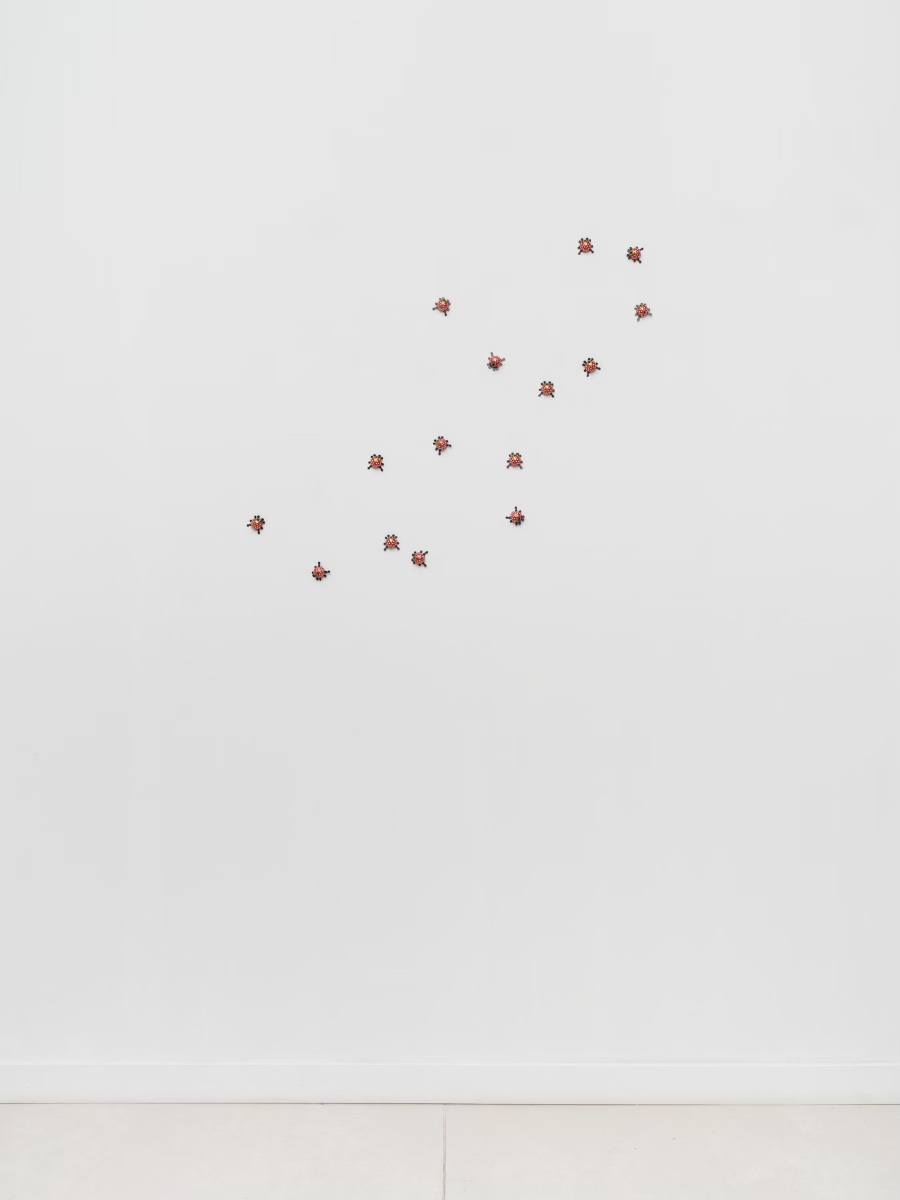

I choose artists through an intuitive practice and I research and see what people are up to. What everyone can expect is for there to be no unnatural light source in the gallery, and a myriad of different smells that will call to your own personal experiences. This is what I love about scent, it is so personal. What people should expect is to slow down, to approach the show with a childlike curiosity, and to not judge themselves for not “getting” what the show is about immediately.

Each artist has challenged me, each artist’s practice actually does challenge what I think I know. It’s very, very satisfying when artists do not pose solutions and more so pose questions. I will say that not a lot of sculpture has been given a chance to shine in commercial galleries in New York. And I will say confidently that that is something that I have always advocated for has been sculpture, time-based media, video, long durational performance, text work, conceptual painting and sculptures. I think that we need to slow down and just try to approach it. You know, it’s fine to like seeing a painting every now and then, but what about just hearing a conversation and that’s the work you’re hearing on audio? I just feel like what people can expect is a deep connection with themselves. We all have an allegiance to things that get us up in the morning, or give us the reason to live. That is your base.

With my exhibitions, I think about the arrangement of music notes. With base note, my focus is not only my base, and the sounds that are made with the artworks shown here, but the music you make upon entering the space.

‘base note’ is on view at anonymous Gallery through October 29th.

Credits

Portraits of K.O. Nnamdie by Ryan McGinley