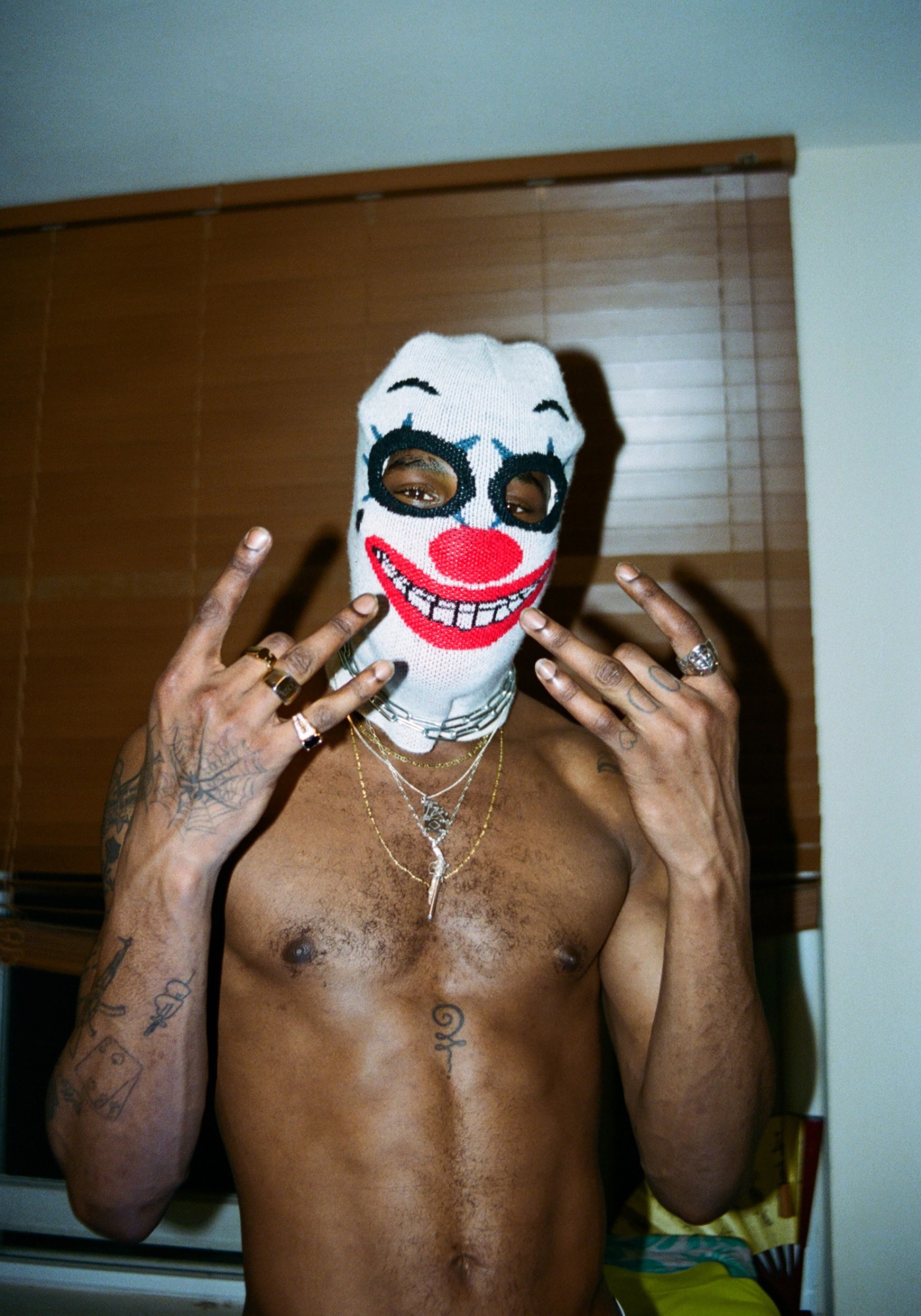

Marvin Bonheur grew up in “le 93,” the Seine-Saint-Denis suburb of Paris. He took up photography nearly a decade ago, retracing his memories of youth through moments of both adversity and affirmation. He has since traveled a much wider perimeter, but always focuses on overlooked communities, most often within the Black diaspora. In 2019, he explored working-class neighborhoods and street culture in London, following friends around Peckham, Forest Hills and Camberwell as they played basketball and communed around cheap comfort food. His latest photo series stems from a month spent on Mayotte, an archipelago situated off of Madagascar, where he held photo workshops for disadvantaged youth themed around identity and territory.

Marvin sorts and classifies his work by typology — tattoos, religious iconography, landscapes, etc. — to represent a place through the most iconic examples of recurrent themes he spots. Beyond his powerful portraits, he hones in on architecture, food and vegetation. He has many forthcoming plans, including: further exploration in Martinique, a series on Lisbon’s gentrification, a project on France’s overlooked rural areas and a soon-confirmed residency in Detroit focusing on the city’s youth population. Whatever the scope or region, “I want to put a face to those who are forgotten,” Marvin says.

With his work recently on display in Paris, at the multipurpose cultural center 3537 in the Marais, we spoke to Marvin about pipe dreams, artistic convictions and the brutal cliché of the ‘no-go’ zone.

How did you decide which bodies of work to present at 3537?

It’s complicated to show new work without explaining where I came from. If you listen to the headphones in the central installation, it’s a conversation about growing up at 17 in a banlieue outside Paris. I wasn’t a good student. As a young Black man from a disadvantaged neighborhood, I felt excluded. The art world was an inaccessible dream. I grew up 45 minutes outside of Paris; going into Paris was five euros each way. You’d feel people look at you when you went — there was a sense of not being where I should be. My school was located in a ‘priority education zone,’ and we were discouraged from pursuing anything artistic.

When I was 15, the woman overseeing training programs explicitly told me to stop dreaming — if I wanted a real future, I’d be better off with an industrial métier, like construction. It was violent. It says so much about how boxed-in French society is: you can only do certain things if you come from certain places. Afterwards, I cried. Hitting a wall like that made me furious; I checked out of school. When you’re young and searching for who you are and you see there are no options, you turn to bad paths. My parents prevented me from going that way.

It seemed impossible to become an artist one day — but I wanted to fight for that anyway. The only thing I was actually good at was drawing. I believed in my own potential, and in the potential of young people from disadvantaged neighborhoods. What got me started with photography was the need to represent myself, [to] explain things that society at large didn’t understand.

I eventually moved into Paris proper, taking over a friend’s apartment, and worked at American Apparel. It wasn’t my culture at all. There were a lot of white employees, 18-year-old Swedish girls on their junior year abroad who’d been traveling all over Europe. But when I talked about my cultural context, people didn’t get it — French people even less so than foreigners. One colleague said, “You speak so highly of the neighborhood you grew up in, but I don’t believe you. I only ever hear about crime, violence, and drugs. If it’s so good — show me.” So I said, “Fine!” I put my neighborhood in the search bar — and the first photo that appeared was a burnt car.

Oh god.

I was like Crap; I can’t show her this. This just confirms it’s the ghetto. That was when I realized that if I wanted to change the vision, I couldn’t expect it to come from the outside world. For years, traditional journalism did a horrible job of stereotyping disadvantaged neighborhoods — a kind of fear-mongering and fetishism around violence. The media’s narrative cycle started at the end, with the riots, without depicting the beginning, the circumstances in which people lived.

In 2012-13, an Irish friend said she wished she could see where I was from because I spoke about it so dearly. I wanted it to just be a cool series about my adolescent neighborhood, but — without even meaning for it to be — the series, La Trilogie du Bonheur, was automatically political.

What made you eventually look beyond the 93?

I turned towards Martinique because those are my origins. I photographed the series 30° à L’Ombre around 2017. I went with my parents to see family there and photographed roadsides for three weeks: food trucks, vegetable stands. I loved it because it wasn’t the 93, but it was still me. There’s a kind of rivalry between people from Martinique who live on the islands, and people from Martinique who live in France. They no longer consider us legitimate Martiniquais, because we’re in metropolitan France, and vice versa: people feel superior here relative to the narrower means there.

Having developed my two identities, I wanted to explore a new territory, but one that spoke to me. I listen to a lot of New Wave — I love melancholy — although it’s complicated if I put those songs on at a party. People are like, “You’re a Black guy from the banlieue and you’re listening to Joy Division?” Uh, yeah, I love it. I went to London with the idea of finding its version of the 93. I spent three years going back and forth, focusing on working-class neighborhoods. Some have really gentrified, but still have this working class history — Brixton, Hackney, Shoreditch, Tottenham…

The gentrification in some neighborhoods is so radical it seems like it’d be tricky to connect with the working class history in a tangible way. Was it?

Although Shoreditch is a desirable area now, there are people who don’t have the means to take advantage of what’s in their neighborhood. These are the ones I followed. What I ultimately wanted to know was how young people in London experience the situation. Paris has the périphérique [ring road], and the banlieue is outside it; London has a similar principle with its zones — but these neighborhoods remain within the city itself. How does a working-class experience within a well-off city compare? Is a young Jamaican immigrant living in a housing project experiencing the city differently than I did? We had a lot of debates: Who has it worse?

Discovering the real London was about discovering the locals who wake up and make the city tick: the people who work in stores, who drive buses. They create the vibe. It’s not the queen, or the changing of the guard, or Piccadilly Circus. Same thing with Paris — local Paris is not the Champs Elysées.

Having been so drawn to urban lifestyles, how did you come to work in Mayotte, an island southeast of Africa?

My work started getting press coverage around 2017. A young woman from Mayotte, Julia, who runs a charity, heard me do a radio interview and reached out. Mayotte is a former French colony, and the biggest slum in all of the French territories. It has the highest number of orphans… It’s like an island of children, which is why I named the series after a Peter Pan reference — Au Pays Imaginaire — because they handle things totally on their own.

We coordinated workshops for young people from difficult socio-economic backgrounds. I was there a month, using photography and design to discuss territory and identity. My workshops focused on portraits. The idea was for each person to see themselves as beautiful, to exalt the other. For the design component, the kids were tasked with making chairs from roadside trash: to make them understand that even when things are damaged or broken, you can salvage them and make them alive again. It’s possible to reconstruct and make something with what you have.

They loved the workshops — it was very moving. If I thought I was excluded, this youth is truly excluded. It’s so unjust. But everything is possible, even if it’s not easy. In speaking with young people, I’m transparent about my own adolescence: feeling lost, being bad at school, having friends get in trouble with the police. I use photography to help young people become sensitized to the fact that it’s never too late to feel encouraged. What I denounce the most is hopelessness. Being excluded from society, from a territory — we lose hope and have the sense that it’ll never get better. We feel abandoned. My work is about preventing that from happening — for hope not to disappear. That’s what saved me.

What is the best way to transfer that sense of hope? How many different communities do you hope to reach?

In this fight, there are two possibilities: helping the communities or alerting the subjects’ problems to other communities. I chose to leave my neighborhood and explain to others what it means to be young there. There was no representation. There are no successful Black French photographers from the banlieue, even today. The only photographer I could identify with was Mohamed Bourouissaa, who is originally Algerian. He’s my friend and a bit of a mentor. But aside from him, there’s not one. I’m proud to be that person for future generations. So many young people write to me on Instagram and Snapchat, 15-year-olds who’ve taken up photography and see it as a possibility. A Black photographer from Martinique who grew up in the banlieue can be published in magazines: I am proof that it’s possible.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more photography stories.

Credits

All images courtesy of the artist.