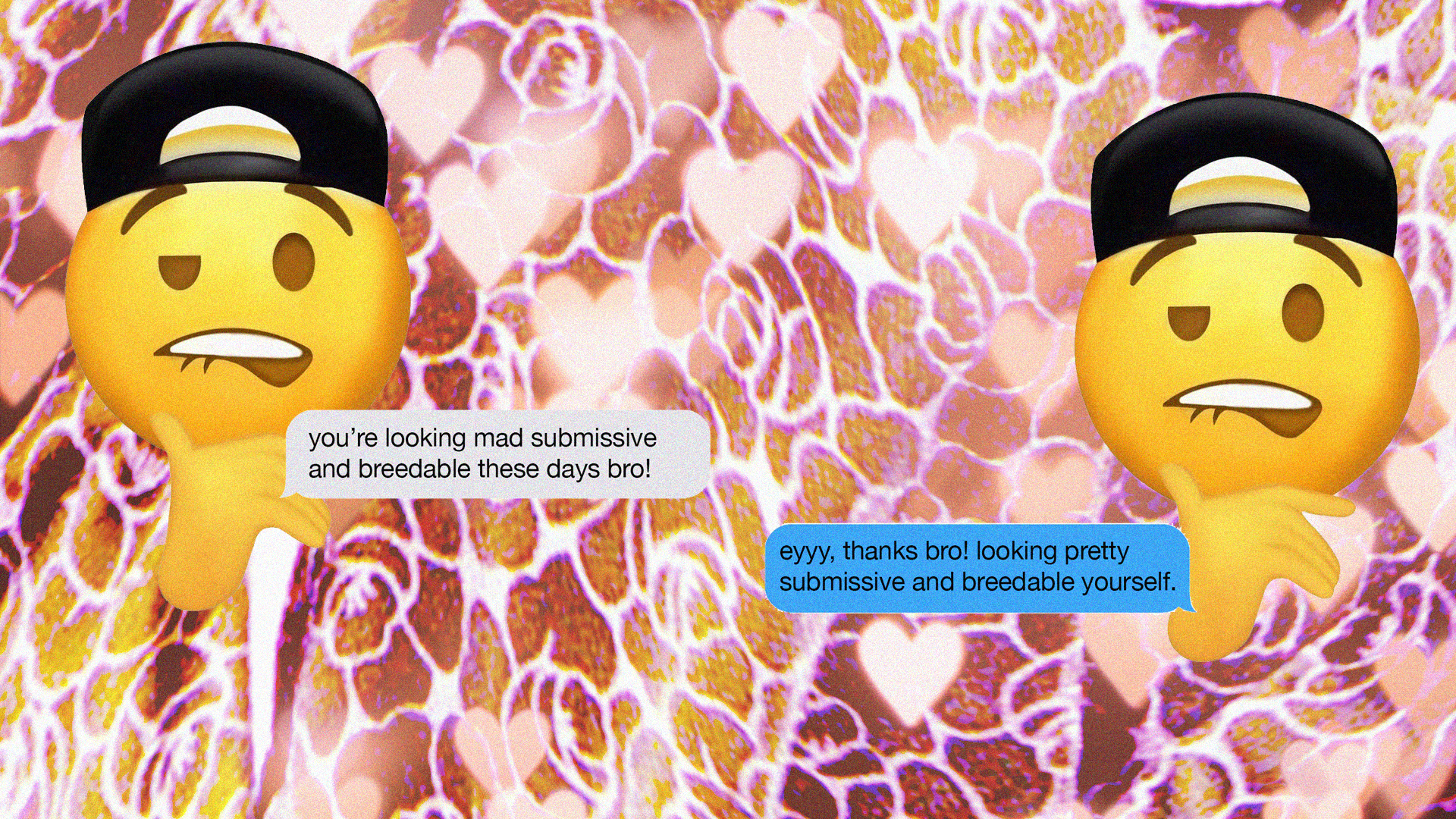

In certain unhinged corners of the internet, it’s been the summer of the ‘submissive and breedable’ bro: the latest phase of baffling online image rehab for men, and a distinctly online way of expressing male intimacy.

Twitter user @T4RIG coined the term back in June when he tweeted: “normalise platonically telling your bros they look submissive and breedable”. Like wildfire, it spread across Twitter and eventually to its inevitable fate: being reproduced ad infinitum on TikTok. Coinciding with what feels like an especially torrid Leo season, this is a high point in men’s Extremely Online sexualisation. Simply put, if your male friend is looking particularly good, then the current and correct way to show affection towards him is by calling him ‘submissive and breedable’. And while none of this is serious, it ultimately benefits anyone keen to eliminate the gender binary.

We’ve had similar iterations of softening masculinity and playful objectification over the past few years, all stemming from a desire on and offline to see men differently. In 2018 the New York Times declared this the Age of the Twink and last summer the himbo got his moment in the sun (unbeknownst to him, of course). For 2021 the Internet has fashioned this shiny new prism through which to view men.

The ‘submissive and breedable’ meme adopts clinical, historically misogynistic language and grounds it in a genuine sentiment. It facetiously calls attention to the dehumanising and ludicrous nature of ‘tradwife’-ish language by directing it at men. Most importantly, when utilised by men against other men, it destabilises hierarchical gender ideals and ridicules the disturbing tendency of men to sexualise women for their reproductive abilities.

@tyler01010101’s above tweet is, essentially, the crux of the meme and its ideological meme bedfellows: that any man who doesn’t position himself as a (sexually) dominant figure is failing his biological initiative. It’s a necessary but ludicrous rejection of gender essentialism that should only be encouraged. The assumption that men must, in any shape, conform to some imagined paragon of dominance and strength needs to be abolished – it is a poisonous, cartoonishly unrealistic burden.

Platonic intimacy is found more organically in female friendships. Women have always been able to directly express physical affection in ways men do not afford themselves, and it’s enviable in its normality. It’s a matter of socialisation, of being encouraged to rely on your emotions instead of downplaying them, of maintaining an infallible facade: “historically, women don’t receive the same messages passed down to them that boys and men do,” says clinical psychologist Dr Robert O’Flaherty. This, of course, is also its own form of gender essentialism, an abiding presumption that due to the historic positioning of women as caregivers, intimacy comes more naturally to them.

The rise of hun culture has been a blessing, a long overdue appreciation for the inexhaustible kindness of the drunk girls in the smoking area who go out of their way to lavish compliments on you. With hun culture comes a form of touchy-feely friendliness that queer men have always identified with. It’s much rarer to find this level of platonic intimacy between men in ways that aren’t played off or dismissed, and where it exists it’s all the more quietly profound. Dr O’Flaherty says that “men learn the language of ‘banter’ as their main communication method and don’t always develop the awareness or vocabulary to express themselves in other ways”. If hun culture is a reclamation of the ‘ladette’ then there must be a similar embracement of the ‘lad’.

“Men learn [early] that intimacy is bad or weak,” Dr O’Flaherty says. “And while this may sometimes serve them well in the short term – [gaining] acceptance from other men in their lives that subscribe to the same view – they often become unstuck in the long term and their interpersonal relationships struggle as a result.” Men often gravitate towards certain cultures for precisely these reasons. “They find connection in team sport where they can develop a sense of belonging and community,” Dr O’Flaherty says. “It’s encouraging now that many sports clubs and professional players are recognising the importance of psychology, not only for performance on the pitch, but in bonding teams, breaking down barriers and creating more emotional intimacy between players.”

Yet football culture has often been regarded as a Petri dish of destructive masculinity and this summer faced an overdue reckoning in England during the UEFA Euro 2020 Championship. England team manager Gareth Southgate penned an impassioned letter urging empathy and compassion from both his players and the fans. Hearing Southgate, a leading figure, state that it is “the duty of [England’s team] to continue to interact with the public on matters such as equality, inclusivity and racial injustice, while using the power of their voices to help put debates on the table, raise awareness and educate” is a step forward for a culture so traditionally steeped in bigotry. Southgate’s words were not heeded — the tsunami of racist abuse that emerged after the final speaks to that — but attempts are clearly being made from the top-down to cleanse the culture of bigotry.

The narrative of men eschewing their emotions and assuming a dominant role continues to be perpetuated in increasingly bizarre ways, cloaked in language of inclusivity. This month, when distressing footage and images emerged of Afghan citizens fleeing their country, many commentators chastised the quantity of male refugees. Photos were cropped to remove women and children and emphasise the gender balance with the implication being that a seismic humanitarian crisis has somehow failed to meet a particular yardstick of diverse representation. This transcends logic and archaically suggests cowardice on the part of these displaced men. In 2021 men, regardless of context, are still expected to lay their lives on the line for the good of others.

Attempts to uphold this unhealthy standard of masculinity can easily descend into unintentional gay mission statements, drawing attention to the extremely thin line between unbridled machismo and blatant homoeroticism. London mayoral flop candidate and national embarrassment Laurence Fox’s recent tweet about the fall of Kabul accidentally turned into a uniquely unhinged Grindr bio:.

To say “hard men make good times” without a sliver of irony speaks volumes to the threadbare logic used by men advocating chauvinistic tough-guy politics. They’re one shred of self-awareness away from joining the dots but until then they’re all just going to accidentally sound very horny.

Sex sage Annie Lord recently wrote that “kissing all my friends, allowing myself to be sexual around them, helped me rediscover my sauce. I saw that I don’t need to force anything because it’s coming, it’s all inside of me, just waiting for the right moment”, and this is precisely the balm for men. If men seek out sexual affirmation and approval from their friends in the same way as women, then it only strengthens their understanding of their sexuality, allowing them to feel corners of desire once unchecked. “A man hugging a male friend can actually convey a lot in a simple action – I care for you, I’m here for you,” says Dr O’Flaherty. “This, in turn, can lead to more emotional intimacy and improved mental health.” Contrary to Laurence Fox, soft men actually make the best times.