Since childhood, Norwegian artist Oda Iselin Sønderland has inhabited fantasy worlds of her own design. Now 26, the recent RCA graduate has lost none of her imaginative zeal, instead channelling her otherworldly visions into ethereal watercolour paintings that combine references to Nordic folklore and Japanese manga with vivid personal memories. For Sønderland’s current exhibition at Marlborough Gallery, Shelf Life, a group show of still lifes curated by Jessica Draper, the artist explores her formative world-building experiences through two paintings shown alongside work by Wolfgang Tillmans, Julie Curtiss and Igor Moritz.

“I grew up playing video games,” Oda says from her Brixton-based studio. “It was a huge part of my development and the development of my imagination. I really and truly experienced it as this magical world that I was completely inside of, and [in my work] I generally like to play with worlds within worlds.” Featured in both paintings is a Nintendo DS, the handheld gaming device instantly recognisable to anyone born in the 90s, and for Oda, symbolic of a time when fantasy and reality remained happily indistinct from one another.

In the smaller of the two works, “The Gift”, a powder pink DS lies on the forest floor, and from its twin screen displays, a naked nymph-like creature frolics within a parallel eden. In the larger painting, “Heart of Glass”, the console is bestowed upon the reclining figure of a woman, eyes ablaze and clad in armour, by a mysterious male figure dressed in a suit. “It’s more like a cursed object [in this painting], because when I was a child I used to be obsessed with the devil,” Oda explains with a laugh. “I was around 10, and I wanted to pray to the devil because I didn’t like that everyone hated him; I felt really sorry for him. We developed this really deep internal relationship, so here he is holding the DS.”

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

With both works backdropped by mystical woodland scenery, a recurring motif throughout much of the artist’s work, the conversation turns to her close relationship with the natural world. “In Oslo you’re always close to forests and beaches,” she says.” It’s a big part of the culture to go hiking and skiing.” Forests in particular serve as liminal spaces for Oda, at once timeless and in constant flux, whose reflective aura she likens to a kind of memory incubator. “There are so many different experiences I can have in the forest and yet it’s always the same place,” she says. “It’s like a box that contains everything, and when I visit the forest I can visit those memories.”

Combining the wonders of the natural world with Sønderland’s fondness for introspection are tales from Nordic folklore, many of which ignited her imagination as a child and left an indelible mark since. From Nøkk, the shape-shifting water spirit who lures victims with enchanted music before drowning them, to Huldra, a forest-dwelling temptress who seduces men into marriage, these morally ambiguous stories remain an evocative source of inspiration. “I would think about these creatures a lot [as a child],” she says. “I was pretty scared of them, but the characters in my work are more like versions, never direct references. It’s like an aspect of myself that manifests through these characters.”

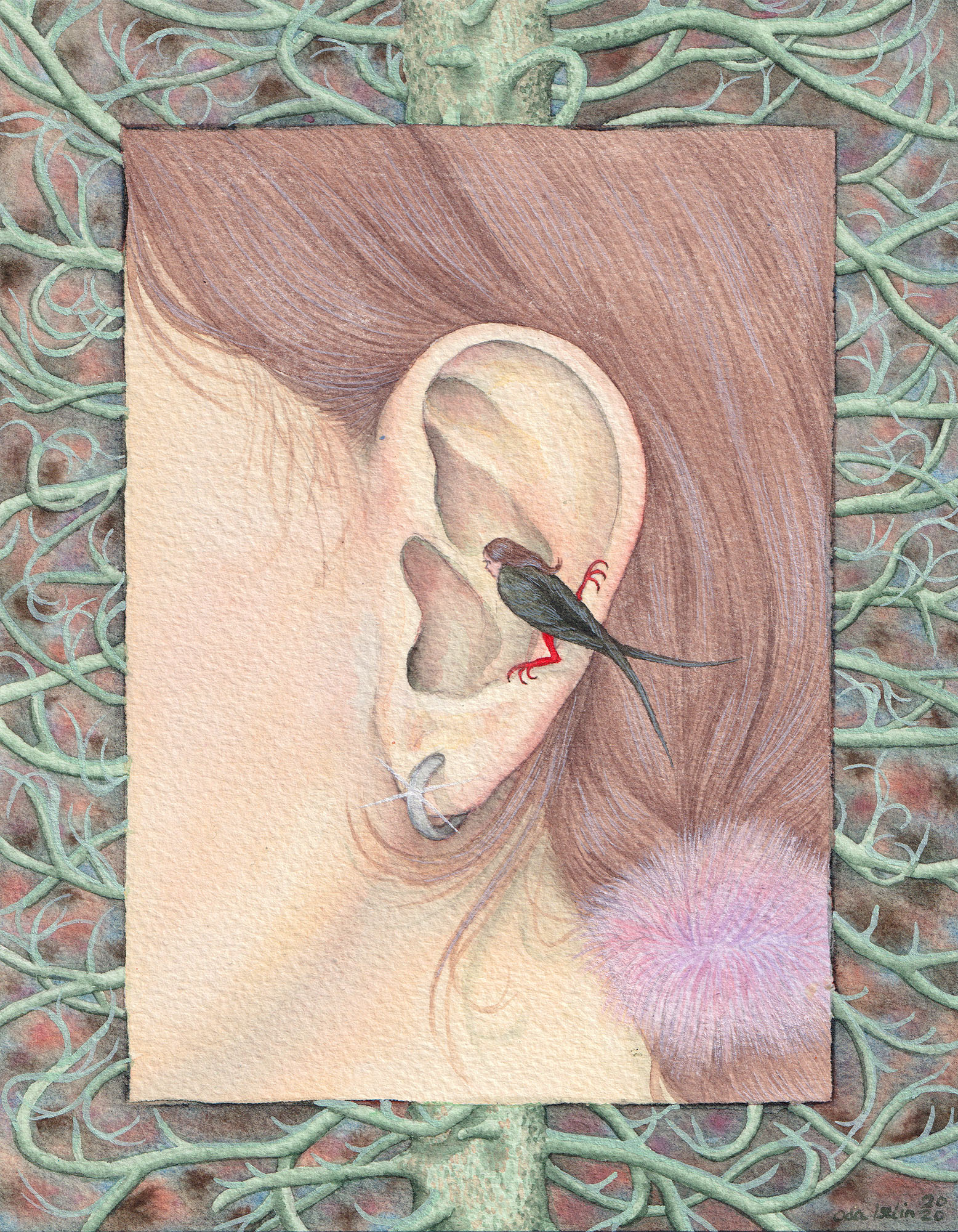

Equally visible in her paintings is the influence of manga and other graphic novels, which in form and composition have left their mark on Oda’s style. In her tendency to set an image within another for example, or framed by an elaborately ornate border, evidence of Sønderland’s undergraduate training in graphic design and illustration combines with her appreciation of revered Belgian cartoonist Olivier Schrauwen. “He likes to play around with the structure of the page,” Oda explains. “He’ll put one part of what’s happening on top of something else so it makes the storytelling more dynamic, there’s more things happening rather than just peeking into this hole into another world. It’s like the actual structure is participating in the storytelling and that was quite inspirational to me.”

Immersing the viewer further into her fantasies is something Oda is eager to emulate herself. With nascent plans for a graphic novel, expanding on the strong sense of narrative that is already so central to her painting seems like a natural opportunity to explore further. “The story needs to grow a bit so I’m not certain when it will happen, but it will be an attempt to bring the world of my work into something that’s more direct,” she says. “I feel like my paintings are keyholes into a world, but rather than just glimpsing at it, the comic will let you enter.”