Italian photographer Oliviero Toscani shot to fame via the controversial campaigns he designed for Benetton between 1982 to 2000, hinging its communication strategy on topical, polemical issues such as AIDS and the death penalty, despite the images being made for a clothing company. In fact, he’s known for creating visuals for many brands that address diverse social concerns, from road safety to anorexia. Oliviero was even involved with the heritage of this very publication — namely the first issues of i-D over 30 years ago — shooting fashion stories in the street with Terry Jones, whom he met while he was working for British Vogue and Fiorucci in the 70s.

To date, Oliviero has five decades of publishing, advertising and exhibitions to his name — but since 2007, he has been working on an ongoing personal project, Razza Umana (Human Race). The visual catalog involves photographing people all over the world.

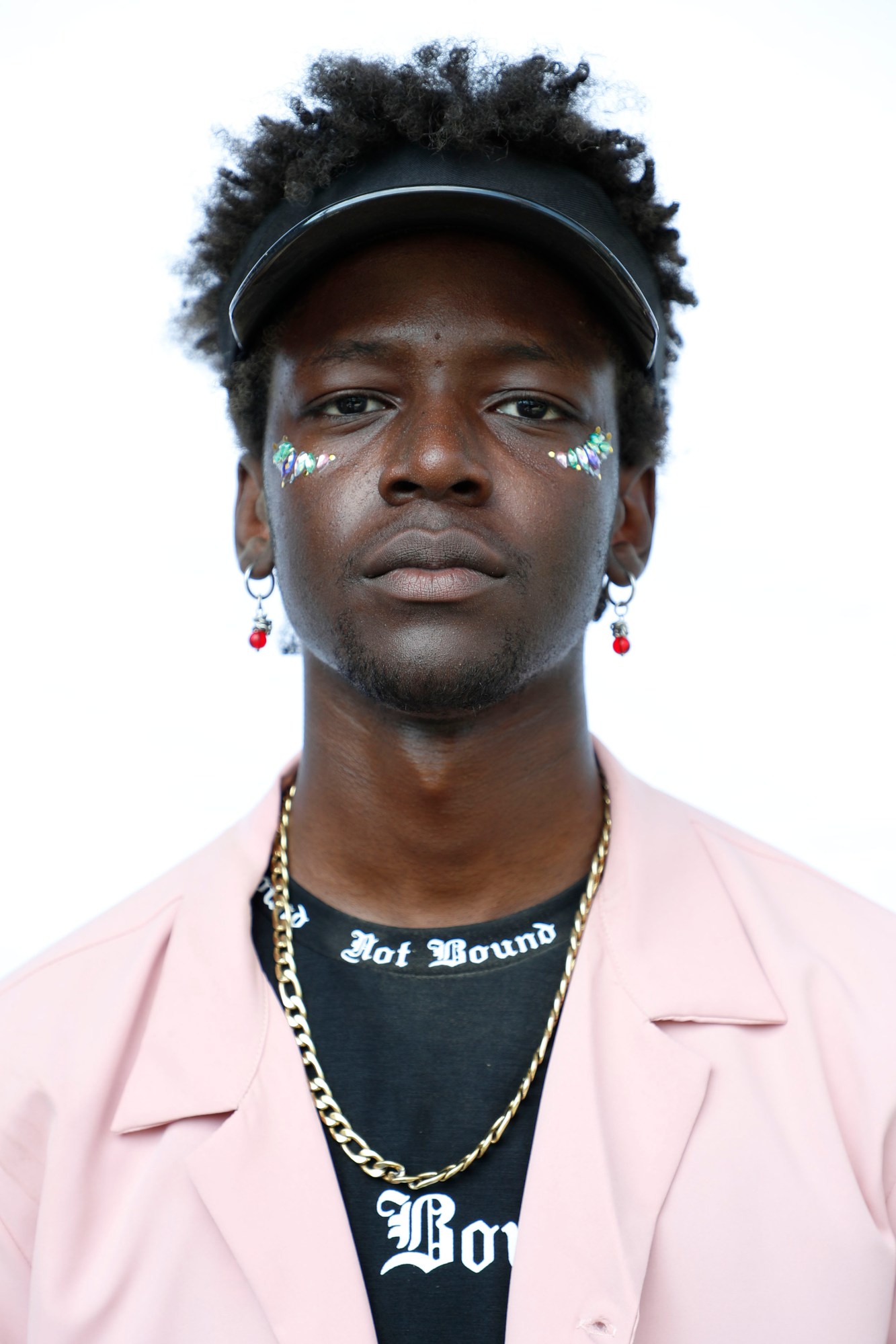

For his latest addition to the series, he went to Turin’s Kappa Futur Festival, shooting a selective typology of glitter-dabbed, multi-tatted, everywhere-pierced, snappily-accessorized stylish figures on site: exemplars of contemporary youth culture. Over the phone from Italy, the 80-year-old photographer discussed the appeal of festivals, his stark photographic approach and believing in first impressions.

What drew you to a festival context? Will you photograph others?

Yes. Most festivals are interesting because you know what kind of people — more or less — you get. It is nice to have ‘tribes’ who belong to the same culture. It’s interesting to see the differences within the culture. What is photography? It’s in the details.

What was your casting process like?

I choose the people, I put them in front of my camera. I tell them to look at me but not to pose — to be what they are. There are ones who are naturally good; others try to be somebody else. They don’t interest me, those with that kind of complex.

Do you have any further conversation before you take the photo…?

No — I’m not one of those photographers who ‘tries to understand who [their subjects] are’. I’m not ‘connecting’! I’m not ‘identifying’! I’m not so presumptuous. People are just passing by in front of me. The first impression is the one that counts.

Would you call it a scientific approach, in a way?

It’s a philosophy. If you’re a singer at a concert, and you have five thousand people in front of you — you don’t know them! But you’re singing for them.

In the Razza Umana series, many portraits feature more austere-looking figures. But in the context of this festival, you’re dealing with youth culture and very stylised looks. What is appealing about them especially?

It’s a very special place to look for certain kinds of people. But I’m going to go to Sardinia in 15 days to photograph a group who are over 100 years old… there is a village [called Villagrande] with a lot of people that age.

How does age affect the way people relate to the camera?

It depends… Age very much influences the brain. So, it depends how much damage you have [laughs]. But there are people who are 20 years old who are already damaged.

What about your own relationship to photography over time — has it changed?

No. I create a testimony — I’m a witness of my time. That is what a photographer is: a witness. That is what photography does: store human memory. We know about history ever since there is photography; before, we’re not so sure what happened. The Bible could very easily be ‘fake news.’

So you inherently trust photography! But photography can be misleading too.

It’s more trustworthy than writing. Through photography, we know the tragedies that humanity has inflicted on one another. We know about the Shoah and Auschwitz; we know about the Berlin Wall. We saw places and faces that we otherwise wouldn’t know. That’s why I chose this topic; it’s as simple as that. I have taken thousands and thousands of portraits all around the world in different locations, with different kinds of people. I set up my little place in the street, I ask people if they want to be photographed — I’ve never had a studio of my own. I just bring a white background, two meters by two meters. I hang it on the wall. That’s it. The most simple thing possible. I try to take everything away, all the setup. I’m a one-man band. No artificial light, no technology — zero. Just the humanity.

You started this series in 2007. Has your understanding of humanity changed between then and now?

Of course there’s change. Life changes, and I do my research to try to understand.

What does that research entail, exactly?

Why do we travel around the world, why do we read books, why do we go to the movies? I just like exploring! I’m the son of a photographer; I’ve had a camera in my hand since I was five years old. I don’t care about landscapes. I don’t care about nature. Nature is perfect. What interests me is the human being, the intersection of human beings, who are not perfect.

Aside from the fact that your dad was a photographer, who are other photographers who shaped your vision?

Richard Avedon and his series ‘The Americans’. He used to be a very good friend of mine.

Did you ever work on anything together?

We didn’t work together, but we saw each other very often in New York.

How do you think about displaying these portraits? In the Naples subway, there was this collaged “unfurling” of people that you presented…

It’s 100 meters of 1500 portraits. I did the composition.

In another display, in a private courtyard, individual portraits were blown up large-scale. Is one of these instances more fitting? Ultimately, do you see these portraits as an ensemble or as distinct?

They’re made one by one — they’re not connected. I connect them.

Why this name, Razza Umana, for the series? It’s so ambitious — such a huge scope.

Why would you call it ambitious? You make it ambitious! I just photograph as simply as possible. I try to take away all the virtuosity of photography. I’m not trying to do one of those aesthetically interesting pictures, which I hate. I try to photograph people as they are. Not how they try to be. Very few people can do that. Most of photography is fake — set up. This is not set up at all.

Given the volume of photos you’re taking, what’s your editing process like?

I choose the faces that I find most interesting, like a director chooses his actors. It’s exactly the same.

Is it easier to photograph someone Italian because you can contextualise the culture?

No, it’s got nothing to do with nationality. It’s very interesting to photograph people who’ve never been photographed — people nobody takes care of. Those kinds of people have got a special look. The derelicts are the most interesting; the bourgeois are the most boring. The models are the worst. They try to be something else and want to be photographed all the time! Magazines love them so much. They have to have top models, otherwise you don’t sell the magazine. But I started street casting with Terry Jones! You can write that. And a lot of people who became top models did their first photographs with me.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more beauty trends.

Credits

All images © Oliviero Toscani